Noor Aldayeh is a digital content creator, but they’ve always been drawn to tangible things. “I’ve always liked physical books,” they tell me. “I’ve always liked cassette tapes, vinyls. Even just knickknacks or trinkets. Even just having small items, I’ve always felt a lot of connection and sentiment towards items in that sense.”

As a half Palestinian dyke, the meaning and urgency of physical archives, in particular — how they last, how they’re protected, how they fill in the gaps — feels especially important to Noor.

Noor, who is 23, is an artist, photographer, writer and activist. They’re also a collector. Of vinyls, of books, of trinkets. Of other people’s stories. The act of collecting when you come from a culture and people that has been heavily colonized and deliberately wiped out by imperialism is an act of love, resistance, and necessity.

“There’s always been destruction of records, especially in terms of Palestinian identity, because when a genocide is occurring, you want to eliminate the people. That’s the goal,” Noor says. “So you’re not just trying to kill the people, you’re trying to kill any record, proof, identity, culture, heritage, tradition, any of these things, you’re trying to erase that as well.”

Recently, Noor started volunteering with the Lesbian Herstory Archives in New York City to create an archival project centering queer SWANA (Southwest Asian and North African) women and gender-nonconforming individuals, starting with queer and trans Palestinians. At a time when Israel is decimating and erasing Palestinian life and culture and when queer people’s lives are being exploited to manufacture consent for this ongoing genocide, the work of archiving Palestinian queer experience is significant on multiple levels.

Noor’s the perfect person to oversee this project for so many reasons. “There was just this microcosm of a lot of things with my specific identity and upbringing that made it so that I care very specifically about this,” they say.

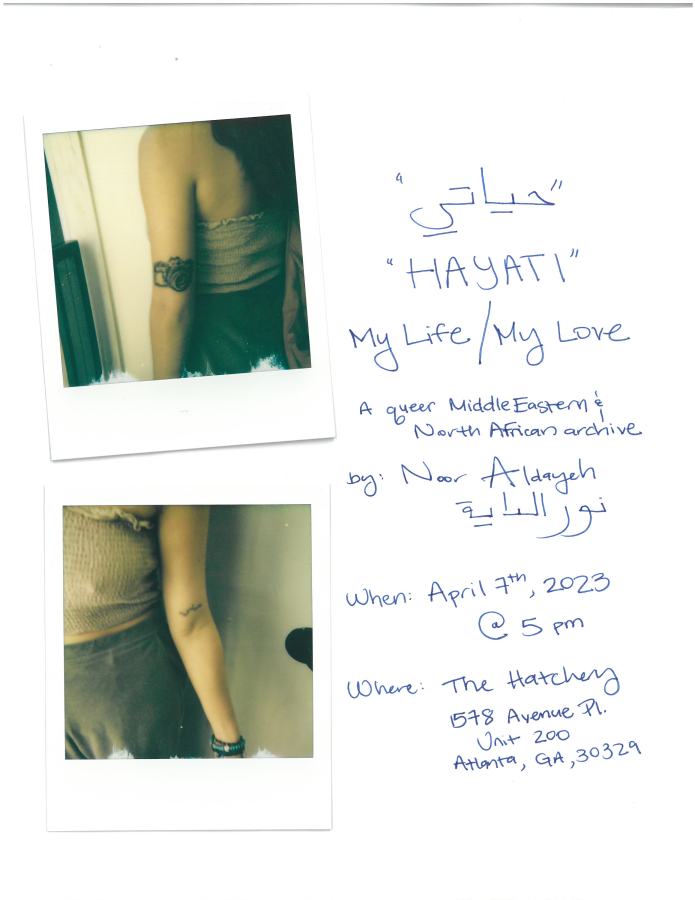

Noor moved to New York in August in hopes of extending their project Hayati, an ethnography and photography-based archive about queer SWANA women and gender-nonconforming people that began as their honors thesis in college. It was working on this project that led to a crucial realization about their life path: “I think I need to do this. I think I need to dedicate my life to telling this identity’s stories.” They’d found their calling, and thus pivoted from pursuing a career in film and media production to dedicate themselves to archiving queer SWANA lives.

Meaningful archival work isn’t merely concerned with the past. It’s concerned with the past, present, and future all at once. Archiving is an active process. And queer archival work is especially vital, because it can shed light on lives and identities that had to be hidden publicly. Archives can often work toward filling in history’s gaps.

Through their work with Hayati, Noor indeed was starting to fill in gaps, but she quickly learned that finding queer SWANA sources was difficult. The majority of what did already exist centered or predominantly featured gay men. Noor was happy this representation was out there, but she knew it wasn’t the whole picture and didn’t get at some of the nuances of difference within queer SWANA identity.

A month after moving to New York to continue the project, the genocide in Palestine escalated.

“I basically dropped everything I was doing and just committed full-time to content creation,” they say. “I’m not making any money off of it or anything, but I just was like, ‘this is what I need to be doing.’”

They discovered the Lesbian Herstory Archives while looking up museums to visit (Noor excitedly and charmingly refers to themself as a certified Nerd™ throughout our interview).

Founded in 1974 by lesbians of the Gay Academic Union, the Lesbian Herstory Archives in Brooklyn are completely volunteer-run and the largest lesbian archives in the world. Until the 1990s, the archives were on the Upper West Side in Manhattan, housed in co-founder Joan Nestle’s actual apartment. They were moved to a brownstone in Park Slope purchased by the founding group — which in addition to Nestle included Deborah Edel, Sahli Cavallo, Pamela Oline, and Julia Penelope Stanley.

For their first few months in New York, Noor was so immersed in activism for Palestinian liberation that they didn’t have a chance to visit the archives. They finally made time to go on their birthday. “I was just like ‘I need to do something that brings me joy. And the thing that’ll bring me joy right now is to read about lesbians.’”

“I’m a gay child of immigrants from a white conservative town. I spent a lot of time in libraries,” she adds. Libraries were where she discovered herself and felt safe, a feeling that has lasted into their adult life as they’ve sought out the safety and comfort of archives, of collections like the personal ones she keeps.

So Noor went to the Lesbian History Archives and did what they always do in queer spaces: looked for SWANA representation, to see lives like their own. Sometimes, they’ll get lucky and find one. As in, literally, one.

She says it was kind of like that on that first visit. She found one Syrian lesbian folder. Noor is half Palestinian, on their mother’s side, and half Syrian, on their father’s side. “So to find a Syrian thing, I was like ‘Oh my god, Syrian lesbians!’”

It was one piece of paper that detailed a really tragic story. And while they were happy to see any representation at all (“Okay, this is true and real and I love it”), they were eager for something beyond that one tragic story. They’d gathered more sources for Hayati than the massive Lesbian Herstory Archive had. Another gap was coming into focus.

Noor returned to the archives on Nakba Day, the annual remembrance every May 15 for Israel’s violent expulsion of more than 700,000 Palestinians from their homes and communities. Noor says they were trying to preemptively self-care on a day when they knew they’d be even more upset than usual. Self-care can look like a lot of things. For Noor, it looks like being in the archives. “This is just how I deal with things,” they say, “by being a nerd.”

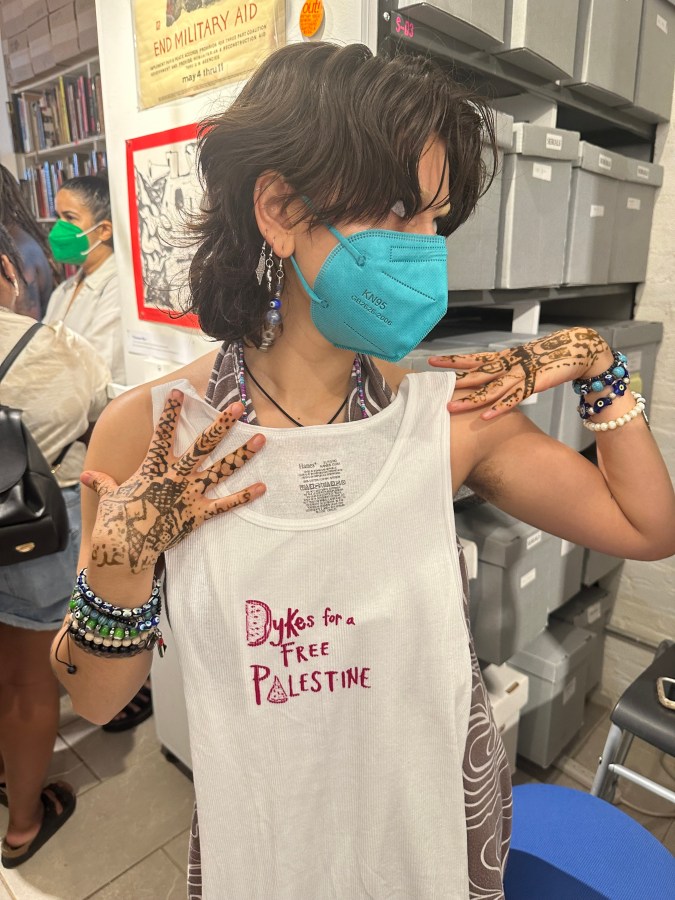

While there, they overheard some other volunteers say “Dykes for Palestine.”

“I whipped my head and I walked over and I basically was just like ‘Hey, I’m a Palestinian dyke. Do you have any of those to do any of this work? Because this is kind of my whole schtick.’”

It was a true “right time, right place” kind of moment and a natural next step for Noor. “I’ve just felt this responsibility almost, like this really incessant need and responsibility to do this work,” Noor says. “Sometimes it feels like certain things are being done, like the ancestors are calling you to do it. Hayati felt like that, and I think this feels like that, where I just know in my being, I’m like, ‘I need to be doing this.’”

That sense of calling and purpose is palpable just from talking with Noor, whose entire energy lights up when they’re talking about especially nerdy shit. In talking with them, it’s also just so clear to me just how thoughtful and intentional they are with both their work as an artist and activist. Their main artistic practice is photography, but they’ve worked in “a little bit of everything artistry-wise.” And then when it comes to activism, they’ve “been involved in a lot of movements through time.” When Noor started in advocacy, they were mainly organizing around disordered eating. They struggled with bulimia from ages 12 to 18 and started speaking about mental health really young. While still actively dealing with disordered eating, they were talking about recovery to help others.

Revisiting my conversation with Noor, I keep thinking about the concept of queer time and how the collision between the past, present, and future is reflected in queer archival work. You can be in the throes of disordered eating while still advocating for and raising awareness about recovery for others. Queer liberation is not a straight line — like how ACT UP NY, which Noor is involved with, is bringing back its messaging of SILENCE = DEATH from the AIDS crisis and reapplying it to the genocide in Gaza.

Noor says they grew out of mental health advocacy and then shifted priorities. “And I always include all of my prior advocacy in the future work I do,” she says. Again, queer time.

They started making educational videos on TikTok about queer SWANA identity and experience in 2021, and after October 2023, they were doing full-time news content about Palestine every day.

The Lesbian Herstory Archives presented a new opportunity to build on the work Noor was already doing. Since 1948, as an occupying force, Israel has intentionally destroyed archives, libraries, universities, family records, and one-of-a-kind documents in Palestine. This isn’t a new phenomenon but rather an ongoing one, one that haunts Noor and countless others who have been impacted by it.

The significance and grief of lost items is deeply personal for Noor. The place where their father’s from in Syria has been severely impacted by the war there, and his childhood home was demolished.

“My dad’s a huge audio file music nerd, and I inherited that from him,” Noor says. “And he’s a music nerd in an old-fashioned way. So I’m kind of old-timey. I like vinyls and cassettes, and he used to collect those.”

Noor was born in California. Her parents were immigrants in a very white suburb where there weren’t many other immigrant parents. Other kids would tell stories about their parents living in LA in the 70s and seeing Led Zeppelin for $10. “And I’d be like, ‘oh my god, that’s so cool. My dad raised me with Led Zeppelin. He was in Syria, and they didn’t go there, but sick. And I had this thing growing up where I was just like ‘Dad, I want all of your vinyls. All of my friends get all of their parents’ vinyls, and I want them.’ And he had to be like ‘Hey Noor, I literally don’t know if they exist or not. I don’t know if my parents were able to evacuate all of my cassettes and vinyl records from our childhood home, which I know has been demolished.’” From a young age, Noor had to reconcile with that part of their Syrian identity. You might not think about vinyl collections and cassettes when you first hear about destroyed homes, but it’s all part of how culture is destroyed.

Noor was raised to preserve culture and tradition even without anywhere to put it. Her grandparents on her Palestinian side were exiled, and so was her mother and all of her siblings. They’re all barred from returning to their homeland. The only way Noor might be able to go to Palestine one day is due to their American citizenship. Archiving in the face of exile is difficult — and purposefully so. Barring whole families from returning to their own homes, their own land, is an attempt to expel their customs, traditions, and yes, personal things.

“We come from not only ancient cultures, but we come from ancient cultures that care about preservation,” she says. “We come from cultures where you know stories that your great-great-great-grandmother told you. Or your great-great-great-great grandmother, and then passed on.”

I’m reminded of Elena Dudum’s essay for The Atlantic, “I Am Building an Archive to Prove That Palestine Exists,” in which she writes of her father collecting 100-year-old magazines about Palestine, about her grandfather reciting his own family tree to her father when he was a child. Elena’s family members start sending her their own personal collections of Palestine. “I’m realizing that this archiving is not only work I have to do, but something I get to do,” Elena writes. And also, “Our liberation may eventually hang on these various archives.”

The intentional destruction of documents and records in Palestine has ripple effects outward, making accessing and preserving records about these cultures and histories difficult everywhere. When Noor was in college and going through the process all new college students do of learning how to navigate databases, do research, and use keywords, she immediately realized it was difficult to find academic sources that reflected her own identities. “Because of ten million layers of things,” she says. “Because of colonialism, because people have hidden those sources, because of my university being Zionist, a billion things.” The forces that exiled her family and that prevented her from finding academic sources reflective of her intersectional identities are all ultimately the same.

After October, Noor was so immersed in creating content about the genocide and doing activism in the streets — both, in their own ways, part of contributing to a living archive — but she was feeling helpless, especially about the permanent losses of family records and one-of-a-kind documents happening on a massive scale.

Again, as the child of an exiled people, this feeling was deeply personal and complex. Noor’s grandfather is from Gaza. “I have this particular difficult guilt that I bear where I don’t know how many members of my family have been killed, because we were displaced,” they say. “So I know I have family there, I know I have direct family there. I don’t know their names, and I don’t know how many of them have been killed, and I’ve never met them.”

Noor spoke specifically about this difficult grief of not knowing how many family members have been killed at the protest of Outright International this June. They’d found a list of names of people killed in Gaza from October to January 31 that included over 40 names of people from her family. That was just up until the end of January. “And things have escalated a lot since then,” Noor says.

All of these contexts — their Palestinian and Syrian roots and the displacement experienced by both sides, their comfort in archives and libraries, their desire to preserve and collect everything from knicknacks to books to stories, their Hayati project, and their grief over mass destruction of culture and records — led Noor to the Lesbian Herstory Archives.

“This is it,” they say. “This is the largest archive of and by lesbians in the entire world. I’ve been seeking to try and preserve those from our identity, and now I physically have an archive that I can do that in.”

Having minored in women’s gender and sexuality studies, Noor says they care about queer history in general. “Not just SWANA, just history, period,” they say. “But with that, SWANA people aren’t emphasized in that or included in that. So that’s why I’m making it a point to so specifically talk about the identities I do…But it’s always grounded in collective liberation and in our collective liberation history at large.”

Just like as Elena Dudum writes in her Atlantic essay that Palestinians have to prove their own existence, Noor talks of how this is especially true for queer and trans Palestinians and of the flawed “logic” of certain Zionists that the existence of homophobia in Palestine justifies genocide. “It’s weird that people are like ‘you deserve to die because your people are homophobic,’” Noor says.

“Make it make sense,” Noor and I both say back-to-back.

“It was colonial white people who enforced [a gender binary and condemned homosexuality], not just on SWANA, on every culture that priorly were very queer in different ways,” Noor says. Not to say that we lived in some utopia where there wasn’t sexism, but we didn’t have ideas of binary.”

“As somebody who is queer and Palestinian and Syrian, when people throw homophobia in my face and it’s a white person, I’m like, ‘I’d like you to go a couple generations up because it’s your fucking fault that I’m dealing with this shit.’”

Queerness and gender nonconformity indeed have always existed, all over the world. Kit Heyam’s book Before We Were Trans: A New History of Gender complicates our understanding of gender and trans identity throughout history. Samra Habib’s memoir We Have Always Been Here similarly works toward an understanding that queer Muslims have always existed, its title a succinct and powerful manifesto of existence.

“We were so gay,” Noor says of distant generations. “And that’s why I think I’m so passionate about it, because the more sources I find, the gayer it gets.”

When it comes to true liberation, getting to the root of homophobia is more important than just talking about homophobia and its impacts.

Archival work is especially urgent in this era of social media, because there’s a false perception that things are being saved and recorded all the time on these platforms. But you don’t own those records; the social media companies do. And as we’ve seen with rampant shadowbanning of accounts posting about the atrocities in Gaza, everything from the biased algorithm to what can be shared and disseminated is controlled by, ultimately, those same silencing and erasing forces that seek to impede or destroy archives.

Even newspapers, often thought of as an accurate historical record for different time periods, cannot always be trusted to reflect reality. I’ve written before about the failures and flaws of journalistic “objectivity,” which often harms queer, trans, and otherwise marginalized groups by putting forth biased dominant ideologies under the guise of objectivity. Lots of content creators like Noor have collected and presented data and analysis of the biased ways mainstream newspapers have covered what’s happening in Gaza (which, of course, those newspapers refuse to call a genocide). In a few generations, if someone were to look back at our current events purely from the perspective of the New York Times, they’d get a very limited — harmful, even — picture. If we look back in history, white newsrooms all over the country failed entirely in their reporting on lynchings of Black people (in 2018, a newspaper in Montgomery even apologized for its biased, incomplete coverage of lynchings, but that’s an anomaly).

“Just general writer integrity, journalistic integrity, I don’t know what the fuck happened to that,” Noor says.

Even though she knew how biased the media is when it comes to Israel and Palestine, Noor admits they were shocked at the coverage immediately after October. “Even though I knew that these systems were the way it was, I was still just like ‘wow, y’all are really just full chest publishing this,’” they say. “It just felt weird, because when you study it, you’re like, ‘Oh, this was in 2000, so things were different then.’…And then now, it’s like, ‘Okay, well, it’s been 24 years, and you’re still being fucking weird.’ So it turns out you’re just weird. Okay. Good to know, I guess.”

This is, again, where archives can correct the record. Because with archives, especially those contained in and protected by the Lesbian Herstory Archives, there’s an emphasis on people preserving their own stories instead of these media companies who are trying — and failing — to tell the stories of others. Archives can also preserve traditional records like newspapers specifically to show their biases.

As Noor explains it: “Things have just gone in a way where I feel like things like archives or libraries are overshadowed or seen as unimportant or outdated or ineffective, when it’s like, no. If anything, this strengthens things like social media or strengthens sources on the internet or newspaper clippings, because we can put all of that into an archive and have record of all of it and then see, ‘Oh, this is how biased it was in the New York Times, but also, Autostraddle covered it in this way.’ And then you have all of it in one place. That’s really important, because we also don’t know if the internet’s going to still be around or if people will have access to that or if they’ll be able to know how to search things.”

We see this impact of archival work all the time when it comes to queer and trans history. The Lesbian Herstory Archives are a prime example of how archives can step in when other institutions and systems fail us. Throughout history, queer books have been banned or destroyed. So many queer stories were lost before they could be recorded. Mainstream media lies about queer and trans people all the time. Again, look at the AIDS crisis for a concrete and obvious example. Or, look currently at the media’s framing of healthcare for trans youth. Queer archival work is always about preserving pasts that have been deliberately hidden or manipulated. Palestinian queer archival work is working against even more tools of erasure.

Noor is undergoing training to digitize materials at the archives so that they won’t just be housed in a physical place — Noor, again, reiterates her love of the analog and the physical — but also digitally so, in the event that anything happens to the Lesbian Herstory Archives, there will be digital backups.

As for how this Lesbian Herstory Archives project will work, it’ll be a two-pronged approach of Noor conducting research specifically around SWANA queer identity and then people collecting and putting forth their own personal archives. This builds on the work the Lesbian Herstory Archives was founded for: allowing queer women and gender nonconforming people to collect and record their own stories. Individuals can create their own folder and file in the archives and add to it indefinitely as well as create specific rules for what the archive should be used for in the event of their death. Some people have a folder of every business card they’ve ever had, documenting all the jobs they’ve held through the years. Others have hundreds of boxes of everything they’ve owned. The archives collect 2D and 3D materials, including digital files, VHS tapes, CDs, DVDs, and cassettes. Drafts of creative work, handmade items, handmade t-shirts, photographs, journals, blogs, ephemera, zines, all of these things and more can be collected.

“People will be able to autonomously, their own self, submit what they want to submit,” Noor says. And that autonomy is especially meaningful to them as a SWANA individual, because a lot of times SWANA stories are told by people outside of the identity and, whether intentionally or not, it can lead to Orientalism. People will submit what they want to submit, and then Noor’s only involvement is on the technical side of processing the materials and archiving them correctly.

This is a forever project, not some one-off stint. “Basically, I got approved to be a volunteer indefinitely,” Noor says. “And I told them, ‘Are you sure? Because I’m going to be here till I die.’ And they said, ‘We have a lot of people who do that.’”

Noor’s indeed planning decades into the future for the various phases and implementations of this project. On the short term, they’re starting with Palestinians in New York or Palestinians who are willing to commute to New York to archive their materials in person. Palestine is always, always centered in their work — going back to Hayati — and in how they talk about everything. “I’m going to start with Palestine,” Noor says at multiple points of our conversation.

There’s a Google doc interested individuals can fill out to sign up for an in-person training. There are systems already in place to anonymize the collections. “And that’s a huge, huge thing when it comes to queer SWANA stuff, is safety, privacy, being able to control who sees what,” Noor says.

If people want to keep their archives completely private and inaccessible to the public and want to just know it exists out there, that’s an option. “But also, if you are somebody like me who’s just like, ‘Not only do I want to be archived, but I want everyone to fucking know, and I want it to be public. And if no one knows me for anything else, I just want them to know an Arab lesbian nerd who cared about this shit was around,’ that’s my legacy and goal. I can do that,” Noor says.

People will be able to look up Noor’s file and find whatever she wants to put in there, whether it’s written work, transcriptions of speeches they’ve given, or even their jackets.

Following the initial first phase of the project focusing specifically on Palestinians in or near New York, Noor plans to expand. “I’m hoping that this will become something that a fuckton of Arab lesbians are just in there doing,” they say. They want to open it up to the whole world.

On their individual research side of the project, Noor will be building up and adding to the Lesbian Herstory Archives’s databases to include more of the SWANA sources Noor has been collecting through the years and will continue to dig up. They’ll be adding new subject files and adding to existing subject files in the archives. “The subject files are literal physical files and these cabinets,” they say. “It’s so fun. I love it so much.” The subject files are sorted by specific words, and it’s implied that the word “lesbian” follows. So, for example, there’s an Arab lesbians file. There’s a recently added Palestinian lesbians file. There’s even a file for astrology.

“So basically, the goal is to get any and every source that we can about identity in this archive, just to have this centralized place,” they say. “And I’m not saying this is the perfect solve. I just know as somebody doing this work that there hasn’t been a place that has happened.”

This work will then radiate outward to other institutions. Noor will be helping create a research guide that will work toward updating actual library and archive databases beyond the Lesbian Herstory Archives with the sources they’ve been collecting. They hope to get other researchers and academics involved, too. “We’ll be able to do things like create our own key search terms,” they say.

This is critical, because keywords often reflect biases and limit one’s ability to easily research sources pertaining to marginalized identities. When Noor was working on Hayati, she had to search “really annoying things,” like “homosexual oriental women” just to find sources about gay Arab women. She’ll be adding keywords to the database and research guides, so that when you look up ‘queer SWANA,’ these sources will come up. “That will be so revolutionary, I feel,” Noor says.

On that note, Noor acknowledges that having access to databases in higher education institutions is a privilege. Google, in theory, is more accessible, but it’s ruled by things like SEO, which is not conducive to research or resource sharing.

“What I’m trying to fill is that gap,” Noor says. “I don’t want just nerds who care about digging through files to find stuff about gay Arabs. I want all people to find stuff about queer SWANA folks. Just being able to search it up on Google and something comes up, I don’t think that should be so fucking revolutionary, but right now, it is kind of harder.”

Noor, a certified music nerd, quotes Nina Simone to me: “An artist’s duty, as far as I’m concerned, is to reflect. the times.”

“For me, it’s all intrinsically related,” Noor says of their activism and art. “My art is an embodiment of me and what I believe in and the things I want to do. And as such, it embodies all the things I care about and advocate for as well.”

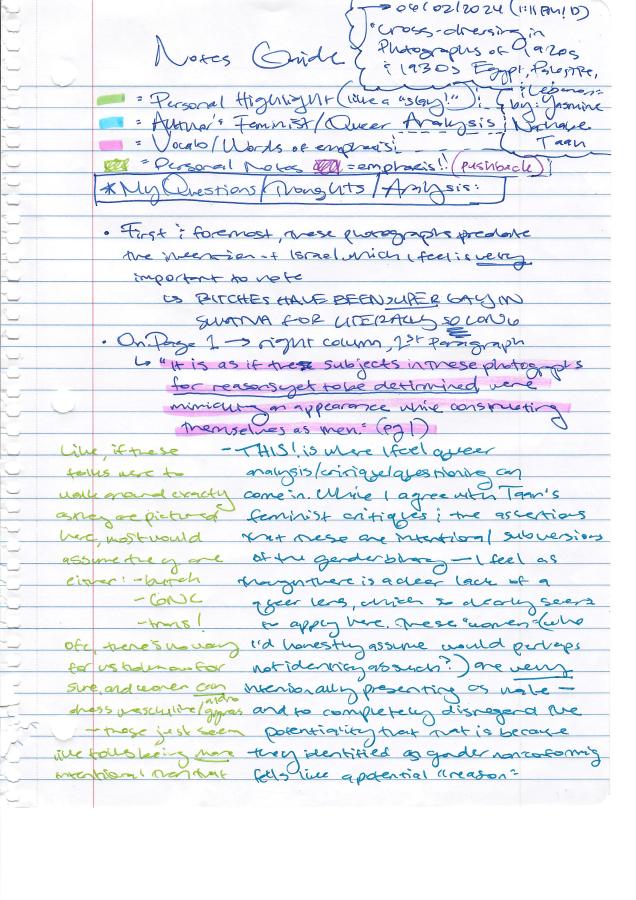

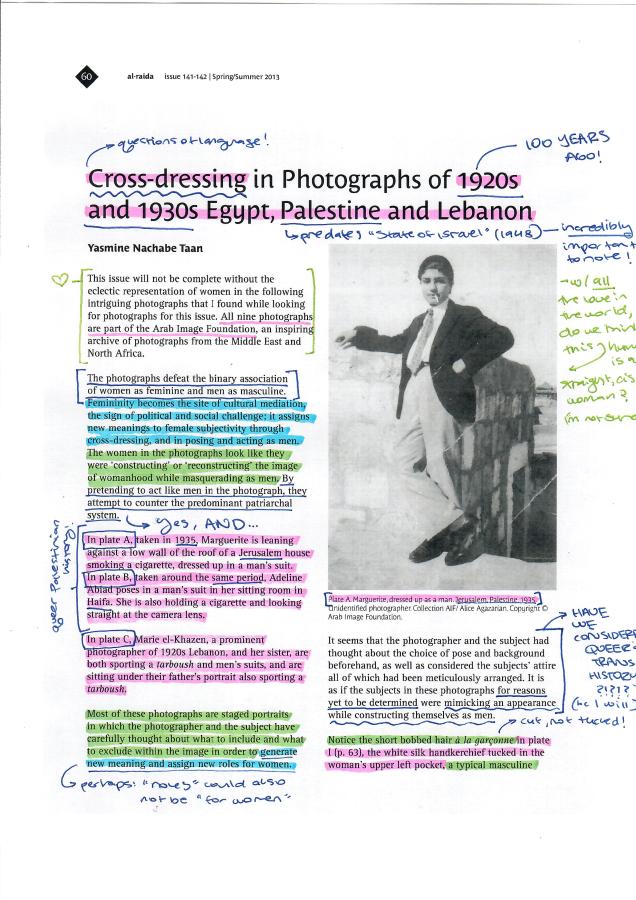

Hayati operated as both a photography project and an ethnography project, perfectly encapsulating this combination of art and advocacy. Even Noor’s Instagram grid similarly presents a dynamic mix of all these threads of their work: art, advocacy, activism, and archives. There’s a mix of selfies (gotta feed that damn algorithm), fundraisers, protest images, reposts of folks on the ground in Gaza, and even a little series called “Noor’s Notes on,” where Noor posts scans of annotated historical documents pertaining to queer SWANA experience, her handwritten notes often expanding on and filling in the gaps of the documents. Take a look (click on an image to make it larger):

Noor does hope to one day see the things that have been taken from their family. “I’d love to go to Gaza,” they say. They want to see if their grandfather’s house is still there, though they admit they have no way of knowing if it could possibly be. They want to meet their family there.

“Not knowing about my family because of the way we’ve been displaced, and then also because of that, not knowing what has been destroyed or not, I’m just left to sit and wonder,” they say.

“Will I ever get my dad’s vinyl records? I don’t know. I hope fucking so. I’d really love to play a Pink Floyd record from Syria in the 70s.”

Comments

Terrible content.

Why? I dislike AS’s view that Zionism is bad per se: (I think Israelis and Palestinians share the same homeland, the problem is the Israeli displacing, and the violence on innocent civilians of both sides). But what’s bad about archiving gay Palestinian experiences?

What’s terrible about this?

As a library and archives nerd, I love this! Thanks Kayla for this in-depth reporting!

this is so beautiful, what amazing work, I am so glad this archive exists and for the dedication Noor has!

this is so freaking cool. thank you Noor for doing this work, and thank you Kayla for bringing it to our attention!

Amazing! Thank you Noor (and Kayla!) Free Free Palestine!!!!!!!!

I love this 😭

Love this so much! Such beautiful & inspiring work that Noor is doing! Great article! FREE PALESTINE 🍉🇵🇸🫒

This is insane. Homosexuality is outlawed by Islam. In Gaza, Iran, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, homosexuals are murdered for the crime of being gay! There is only one country in the entire Middle East in which being gay (or any member of the LGBTQ+ tribe), is not only not a crime, but is accepted and that country is Israel! There Pride marches every year in both Tel Aviv and in Jerusalem! The author if this piece would suffer an “honor killing” if she were in Gaza or any of the PA controlled territories in Israel!

Your argument provides even more reason to archive the experiences of queer Palestinians (and hopefully other Middle Eastern Muslim people). If homosexuality is outlawed then people’s voices and culture will be erased, and it becomes even more important to preserve them through archives, right?