When I was 19, my first girlfriend tattooed a dove on my hip with the word “PEACE,” in all-caps, written on its belly. I was home for the summer after a year of college spent immersing myself in anti-war activist work in Chicago. I was proudly identifying as a pacifist (and more nervously identifying, for the first time, as bisexual). Within a year, so much changed — the relationship fell apart and my politics dramatically shifted; the dove and my queerness endured. Another year in Chicago’s activist community pushed me to understand my own positionality — as a queer woman, as a sexual assault survivor, as a person who grew up on food stamps — as deeply political. I hungrily read more about the history of my queer elders, my working class elders, my feminist foremothers, and realized that no social change has occurred without some kind of militant element. Suddenly my pacifist mantras seemed naive and also dangerous — who was I to condemn the use of violence by an oppressed group? Who was I to suggest those experiencing systemic violence don’t have the right to use any tool available to crush it? I went from a “bleeding-heart pacifist leftist” (this was legit my MySpace bio) to an organizer who respected a diversity of tactics, and who believed in challenging the system by any means necessary.

Despite some reminders from queer Tumbr that “Stonewall was a riot!”, most of the the modern LGBT movement I see in my day to day seems more invested in the less aggressive Love Wins!. While Pride is, at least tacitly, the celebration of the property destruction and cop-bashing that took place at Stonewall, its ties to respectability politics (and corporate sponsors) in recent years are commonly acknowledged. It seems important, then, to reflect on the use of militancy (and yes, violence) in our queer history. Not just from our patron saints Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, but also from other ancestral queers who fought oppression with glass bottles, fists, and, yes, even guns.

The use of violence — organized or spontaneous — in the fight for social change is not new, nor is it relegated to queer movements. In This Nonviolent Stuff’ll Get You Killed, Charles E. Cobb explains how the use of armed self-defense enabled the nonviolent Civil Rights movement to exist. Cobb notes, “…wielding weapons, especially firearms, let both participants in nonviolent struggle and their sympathizers protect themselves and others under terrorist attacks for their civil rights activities. The willingness to use deadly force ensured the survival not only of countless brave men and women but also the freedom struggle itself.”

As so many marginalized groups throughout history have come to realize, “violence” is context is an act of self-defense against a State that systemically enacts harm against non-dominant populations. For queers, the use of force is multi-functioning: it is an act of resistance, a method of self-defense, and a slap in the face (sometimes literally) to the discursive devices (see, for example, this Roy Cohn speech from Angels in America) that deem “homosexuals” as inherently feminine, weak, powerless. Survival, it turns out, is a question of power, and the examples below reveal the ways in which power must often be battled for.

And, as you’ll see below, “militance” can take many forms, some that we wouldn’t normally recognize as “violent.” In Joyful Militancy: Building Thriving Resistance in Toxic Times, carla bergman and Nick Montgomery note that militancy can be understood as “the capacity for refusal and the willingness to fight” and that this can “be enabling, relational, and open up potentials for collective struggle and movement in ways that are not necessarily associated with control, duty, or vanguardism.”

Regardless of whether you ultimately see the use of militant force as an admirable tactic, the truth is that any progress the queer community has made is at least in part to all those queers who refused to play by the rules, the queers who behaved badly, the queers who believed that unjust laws must be broken as a method of survival. Or, as the ruthless 1990 queer manifesto, “Queers Read This!” explains:

“Your [sic] immeasurably valuable, because unless you start believing that, it can easily be taken from you. If you know how to gently and efficiently immobilize your attacker, then by all means, do it. If you lack those skills, then think about gouging out his fucking eyes, slamming his nose back into his brain, slashing his throat with a broken bottle — do whatever you can, whatever you have to, to save your life!”

As a working-class-raised queer femme with PTSD and a mom who lives in poverty, I have a deeply personal stake in the world getting better. My commitment to investigating and sharing histories of militance stems from a real passion for actual systemic change and a belief that militancy is a tactically necessary part of that.

Below are more examples of some of the other militant queer actions and organizations who have struggled for queer liberation, using all the tools they felt were available to them. While the motivations and approaches to violence are mostly distinct from each other — some spontaneous eruptions of violence as self-defense, others calculated and strategic actions rooted in radical militant traditions — they all managed to create blows to the oppressive status quo. Whether through protecting their own bodies against police brutality, reducing the cost of AIDS medication, or simply creating a counter-narrative that enabled more mainstream LGBT groups to gain traction, their militancy pushed progress.

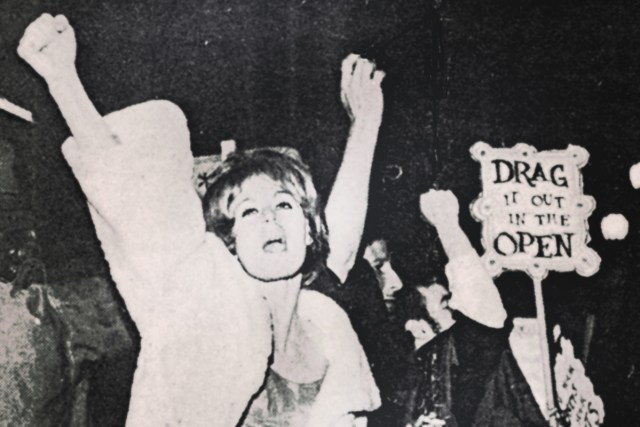

The Compton Cafeteria Rioters

In 1966, three years before the riots at Stonewall, transgender women in San Francisco stood up to police who were trying to evacuate them from The Compton Cafeteria. The restaurant was in the Tenderloin District, one of the only safer spaces transgender women felt like they could congregate without fear of violence. However, restaurant staff, fearing the women’s presence drove away customers, called the police to try to remove them. When one police officer tried to handcuff one of the trans patrons, she threw a cup of hot coffee in his face. The other trans women at the restaurant began throwing dishes and furniture, and eventually the restaurant’s front window was smashed.

In the days that followed, some other members of the queer community came out in solidarity with the riot, and in protest of the women’s arrest. The queer youth group Vanguard staged a protest of the police and the lesbian gang The Street Orphans also joined in the fighting on the night of the riots.

In her account of the riots in Transgender History, Susan Stryker notes, “The violent resistance to the oppression of transgender people at Compton’s Cafeteria did not solve the problems that transgender people in the Tenderloin faced daily. It did, however, create a space in which it became possible for the city of San Francisco to begin relating differently to its transgender citizens — to begin treating them, in fact, as citizens with legitimate needs instead of simply as a problem to get rid of.”

The Central City Anti-Poverty Program opened the following fall, and it included a liaison to work with the police on changing their treatment of trans people. Around the same time, trans activist Wendy Kohler began working with the San Francisco Public Health Department to implement attention to trans health issues, and a few months after that, the first trans peer support group formed, called Conversion Our Goal.

Like Stonewall, the Compton Cafeteria riots were borne of a spontaneous response to targeted physical harm, and like Stonewall, this action paved the way for broader structural change.

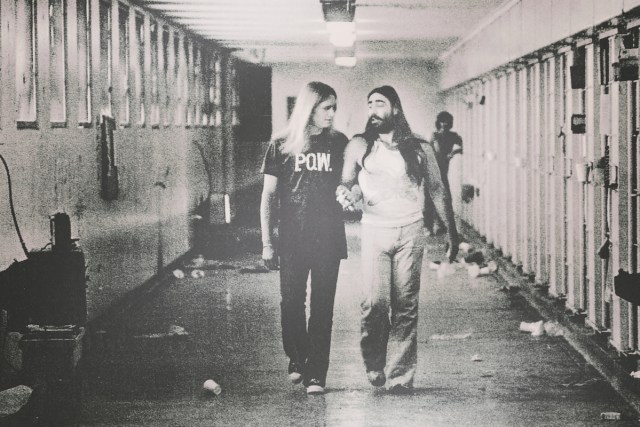

George Jackson Brigade

The George Jackson Brigade formed in 1975 by a group of radical gays and lesbians who sought to overthrow the prison system (and the entire US government along with it). The Communist-identified group named itself after the Black Panther Party member who was killed in his attempt to flee from prison. In a series of communiqués, the organization took responsibility for robbing banks, planting firebombs at racist company’s locations, and other decidedly violent acts of resistance and direct action.

In one of the organization’s communiqués they explained their view on crime, which is both a defense of marginalized people whose behavior is criminalized and a condemnation of “bourgeois” behavior that is not: “Crime is the natural response for those caught between poverty and the Amerikan culture of greed, aggression, sexism, and racism… The Amerikan people support the most notorious criminals in existence: U.S. imperialism.”

For the queer members of the brigade, violence was one of many tactics they felt was necessary for defeating oppressive systems of capitalism, imperialism, heterosexism, and white supremacy. In one of their communiqués taking responsibility for a planted bomb, they begin with a quote from George Jackson himself: “…any serious organizing of people must carry with it, from the start, a potential threat of revolutionary violence.” For the brigade members, who studied the likes of Lenin and Mao, violence was an absolutely vital tool for establishing an actual threat to the bourgeois and white supremacist carceral state. In another communiqué they explain that their insistence on armed struggle was both a short-term tactic that can “cause material damage to the ruling class” (including robbing banks as a method of wealth redistribution; bombs that damage the business and resources of oppressive institutions; etc.) and a long-term praxis that prepared them for the revolution in the US they believed was “in our future like a ship on the horizon.”

White Night Riots

In November of 1978, Dan White, a disgruntled former Board of Supervisors in San Francisco, shot and killed SF Mayor George Mascone and the first out-gay elected official, Harvey Milk. Six months later, White was convicted of voluntary manslaughter (and not, meaningfully, the harsher sentence of first-degree murder). Reports suggest that because White was also a former cop that the SFPD colluded to get White a reduced sentence (including raising over $100,000 for White’s defense).

In response to the lenient outcome, gay organizer Cleve Jones led a nonviolent march in protest. However, as the march grew so did the police presence — and the protesters’ anger. Police had been instructed to hold the crowd back, but the cops quickly began beating protestors with their clubs. As the fighting intensified, rioting began, leaving numerous police cars and parts of City Hall destroyed and causing hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of damage. After the police dispersed the crowd with tear gas, some rogue police officers broke off to assault perceived-queer people in the Castro and also vandalize parts of the strip. The officers faced no disciplinary action.

This night, later dubbed the White Night Riots, compels us to ask who is allowed violence and who is not? Who is punished for it and who is left unscathed? The courts failed them, the police did too, and so in response, the queers of the White Night Riots channeled their rage into destruction. Like many of these examples, the rash property destruction ultimately resulted in a shift in consciousness around LGBT justice (in this case, it contributed to Milk’s legacy which would result in hundreds more LGBT people in office and in leadership positions). However, even if nothing came from it other than some smashed up police cars, the spirit of queer militance urges us to understand that it does result in change.

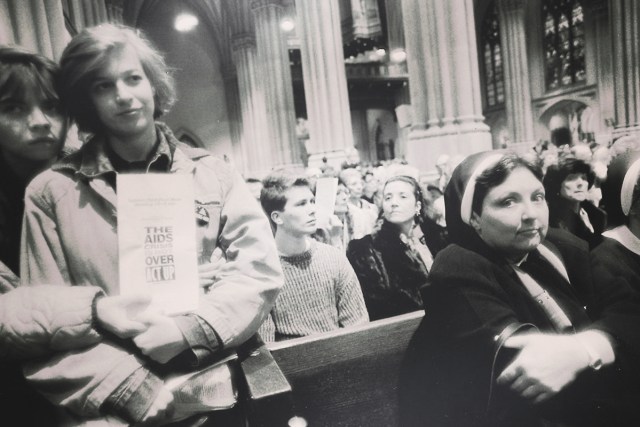

ACT UP

ACT UP (the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) was born of not just the AIDS crisis, but the government’s neglect of it. The lesbian and gay members of ACT UP were “committed to direct action to end the AIDS crisis.” Their forms of direct action included public “die-ins,” occupying buildings, banner drops, and “zaps” which targeted specific companies and organizations with disruptive behavior.

ACT UP (the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) was born of not just the AIDS crisis, but the government’s neglect of it. The lesbian and gay members of ACT UP were “committed to direct action to end the AIDS crisis.” Their forms of direct action included public “die-ins,” occupying buildings, banner drops, and “zaps” which targeted specific companies and organizations with disruptive behavior.

Stop the Church, one of the more divisive ACT UP actions, involved interrupting a service at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City and distributing condoms and safer-sex material to people in the pews, all the while shouting about the complicity of Cardinal John O’Connor and the Catholic Archdiocese in preventing AIDS education and treatment. In a reflection about this tactic, former ACT UP member Patrick Moore reflects on its relationship to violence, or at least conceptions of violence:

“I think we alienated a lot of people with Stop the Church, but I think they were mostly people who were kind of already vaguely supportive of what we were doing. They were like rich queens who kind of didn’t want to be associated with anything naughty – who were still part of the establishment. So, who cares, really, if you alienate those people, because they weren’t doing anything anyway. But, what I think it did for ACT UP is that it made people feel that we were violent, even though we didn’t do anything violent. It was so emotionally violent, that I think that it really raised our effectiveness in terms of, maybe the government taking on larger issues, or just having to deal with this somehow.”

As Moore notes, violence (real or perceived) is a tool, and one that sometimes works. In Moving Politics: Emotion and ACT UP’s Fight Against AIDS, Deborah Gould explains that during the Bush-era mainstream narratives of ACT UP either framed the group as terrorist-level violent or, in total contrast, “simply ridiculous or silly.” These contradictory discourses created rifts in the broader gay community, creating divisions on the basis of respectability. In an interview, ACT UP organizer Larry Kramer describes this as the “dual strategy” of “the kids on the ground” (coordinating direct action that was sometimes categorized as violent) and “the people inside [of government buildings and pharmaceutical companies] doing the negotiating.” Kramer explains, “at some point, as things got really awful, I became much more militant in visualizing ACT UP as an army, which didn’t go down very well. I think at one point, I actually tried to interest people in taking shooting practice.” The dual strategy of ACT UP proved effective in many ways — direct action got attention, in-the-system negotiating got tangible change, but it also created tension in the organization that Kramer credits for its demise.

Without the militancy, though, ACT UP couldn’t have won what it helped win — ultimately a world in which HIV is not usually a death sentence.

Bash Back!

Bash Back! was a group of radical queer and trans folks that started in Chicago in 2007 and formed chapters throughout the country until around 2012. The group was a response to liberal LGBT politics, including the centrality of gay marriage in the “movement.” In response to this and other more middle-of-the-road efforts, Bash Back! took to the streets, churches, RNC and DNC conventions, and more to counter reformism with radical change. For example, the group did multiple demonstrations that targeted the Human Rights Campaign (HRC), one of the most well-funded LGBT organizations in the US. One involved vandalizing the HRC headquarters in Washington, DC with black and pink paint, glitter and the message, “Quit Leaving Queers Behind.”

Some of their other slogans and messaging were more aggressive; one of their more viral protest signs read: “These Faggots Kill Fascists.”

Bash Back! members believed that what destroys us must be destroyed. Uniquely, this included not only state powers, but also mainstream LGBT groups, which they believed upheld and acted in service of state powers. For Bash Back!, anyone who isn’t investing in the abolition of the state is ultimately supporting it.

The extreme rhetoric of Bash Back! and its broader effects have parallels in other movements — Malcolm X’s rhetoric, for instance, was considered violent and inflammatory, especially when compared to that of other leaders, like Martin Luther King, Jr. But Malcolm X took the tack of addressing not only the dominant group, white people, but calling on members of his own community he saw as too moderate or middle-of-the-road to re-examine their stance. And he broadened the Overton window; without Malcolm X, MLK wouldn’t have seemed as (relatively!) palatable to mainstream white America (though obviously Dr. King was also considered deeply controversial by the white mainstream at the time).

In contemporary queer politics and activist circles, there is often discussion of the refusal to uphold “good gays” (e.g. white cis men who want to get married) as deserving of liberation while throwing under the bus the “bad gays” (e.g. trans sex workers of color). And yet, these movements continue to co-exist — intentionally or not — in a sort of symbiosis. The radical queer fringe pushes the mainstream further Left, and the mainstream center continues to make small-scale reforms.

Whether one approach is better or worse is not as important as the fact that, historically and currently, the differing ideologies within the LGBT/Q “community” creates a diversity of tactics that enable changes, big and small, in sometimes material and sometimes conscious or discursive ways.

Trigger Warning Queer & Trans Gun Club

With the uptick in violent neo-Nazi and white supremacist organizing, more leftist groups have begun to train for armed self-defense, and the queers in the Trigger Warning Queer & Trans Gun Club are among them. Like self-defense groups that have come before them (see: The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense) and their contemporaries (see: Redneck Revolt, John Brown Gun Club), Trigger Warning seeks to empower marginalized people and communities with arms training as a method of self-defense and survival.

In their Points of Unity, Trigger Warning explains how vulnerable populations not only can’t rely on the state for protection, but also often need protection from the state itself: “We acknowledge that the police have helped to foment the current crisis of violence and intimidation facing our community through their support for Donald Trump; we therefore acknowledge the need for queer people to organize for self defense.”

Trigger Warning is acting in the spirit of the fighters at the Compton Cafeteria, at Stonewall, and in the streets of San Francisco during the White Night Riots. But instead of acting in the heat of an attack, the members of the group want to plan ahead, to prepare not only for police violence at a riot, but also as a symbolic (and material) warning to far-right extremists who view queer people as, according to member Jake Allen, “weak and defenseless.” He continues, “in many ways [Trigger Warning] pushes back against that.”

There are practical outcomes to armed community organizing — take, for example, the events in Charlottesville, VA where terrorist James Fields drove a car into anti-racist protestors at a Unite the Right rally and killed Heather Heyer. Redneck Revolt, which includes queer members, stood on guard nearby, and accounts of the day suggest that without their presence more violence would have been likely. According to RR member Dwayne Dixon, “[in Charlottesville we] changed the balance of power serving as a deterrent.” Dixon explains his shock when the police left their armed group alone. He continues, “It was a three front struggle: neo-nazis, State power, and us.” And although RR didn’t stop Fields from his attack, Dixon believes, “it communicates something powerful; that a disciplined armed formation in this moment configured the political, social landscape.”

In all of these examples, queers understood that progress requires a diversity of tactics. Polite, in-the-system, and legal means of resistance hadn’t worked on their own, or sometimes at all. So they took a different approach.

And whether queers, broadly, identify these tactics as justified, we are, all of us, inevitable fighters. Whether we like it or not, as “Queers Read This!” reminds us, “You as an alive and functioning queer are a revolutionary.”

Comments

??? if anyone is interested I’d like to recommend “That’s Revolting!: Queen Strategies for Resisting Assimilation” by Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore

*Queer (dammit phone)

Thank you for the rec!

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about how many progressives seem to be putting their faith in the system to eventually beat back the rise of fascism – yet it’s so very clear that the other side is not interested in playing by the rules. So why should we?

Yessss, FKJ-PhD combined with Autostraddle is the best thing to pop up on my twitter feed in a while.

I’m a fan of Feminist Killjoys, PhD, and a fan of this article. Militancy has been on my mind a lot lately. I relocated to Portland two years ago, and I can tell you that (1) Nazi-adjacent groups such as Patriot Prayer and the Proud Boys are 110% serious when it comes to inflicting harm on communities they hate, and (2) the police make no pretense when it comes to showing who it is they serve and protect. Staying peaceful won’t keep anyone alive, and suffering patiently in hopes that the spectacle of that suffering will somehow inspire change is a costly gambit that no one is obligated to play.

“suffering patiently in hopes that the spectacle of that suffering will somehow inspire change is a costly gambit that no one is obligated to play.” Damn. Yes. Thank you for this.

Thanks for this herstory lesson!

I am so, so happy to see this kind of content on Autostraddle.

“he broadened the Overton window; without Malcolm X, MLK wouldn’t have seemed as (relatively!) palatable to mainstream white America (though obviously Dr. King was also considered deeply controversial by the white mainstream at the time).”

^ For folks who don’t know, the “Overton window” is also known as “the window of discourse” and “describes the range of ideas tolerated in public discourse.” (Wikipedia)

I remember being very pleased to learn that more radical/militant strategies actually help movements rather than harm them, by pushing the mainstream further left and making the less radical/militant strategies and demands seem more palatable, which can help get changes made sociopolitically. So, while more moderate or liberal members of movements often try to quiet or suppress radicals/militants in order to make the movement look respectable, radical/militants are actually doing them a favor.

Thanks for all the concrete examples and information in this article, professorfemme!

This is really excellent and a reminder that even non-violent actions by a disenfranchised minority are considered “terrorism” by the powers that be (see BLM).

I went to an anti-Kavanaugh rally with a baby strapped to my chest, which is about as vulnerable as a person can be, and we were portrayed by the media as an angry violent mob. All we did was walk around with signs in front of the courthouse.

The powerful will always use violence against us and we should absolutely fight back.

Slate has had a series going about radicalism and a couple of those articles seem to have a kinship with this one:

https://slate.com/human-interest/2018/10/man-hating-lesbian-insult-reclaim-anger-metoo-activism.html

https://slate.com/human-interest/2018/10/lgbtq-activism-trump-insurgency-radical-pow-resist.html

I’m very much a peacemaker (hell, even the enneagram says so) but I started to recognize that it comes (among other things) from a position of privilege and that it can be harmful rather than helpful. Thank you for this article!

Thank you all for engaging with this piece! I’m so grateful to see the support on this thread. We need liberation by any means necessary – let’s do it. <3

such an important piece, thank you!!

Thanks for the info!

Consider adding the Lesbian Avengers to the list of queer militant groups in recent history: http://www.lesbianavengers.com/about/history.shtml