This Your Love feature was written during the 2023 WGA and SAG-AFTRA strikes. Without the labor of the writers and actors who are currently on strike, movies like this one would not be possible, and Autostraddle is grateful for the artists who do this work. This review contains some spoilers.

Outfest is taking place in Los Angeles between July 13 and Jul 23. Sa’iyda Shabazz and Drew Gregory will be bringing you all kinds of reviews. If you’re interested in attending, virtually or in person, check out Outfest’s full schedule.

A good song can tell a complete story in a short amount of time. One of the things I love most about music is its ability to get a beginning, middle and end in the time it takes for you to make a cup of coffee or wash some dishes.

A short film does the same thing. It doesn’t feel like you can cram a movie into the length of your average radio hit, but it is entirely possible, and I would go out on a limb to say that any storyteller who can make a short film is a fucking genius. When you combine the length of a song with the storytelling power of a short film, you get Your Love, which is screening as a part of Outfest’s shorts programming.

Directed by queer, non-binary, Canadian-Indian actor/writer/director Sundeep Morrison, Your Love is nothing short of an absolute dream of a film. I got the pleasure of sitting down to talk with Morrison. Not only did I get to learn all about their inspiration for the film and their own journey to feeling comfortable in their queer identity, I definitely made a new friend. I love when that happens.

“When I was approached by the record label to write the story, my first question to them was ‘why do you want a queer love storyline?” recalled Morrison. “Is it just to throw something out for the month of June and then you don’t care?’ and they were like ‘no.'”

Your Love is set to Vancouver-based producer Khanvict’s re-mixed imagining of the iconic Punjabi folk song “Ik Tera Pyaar” by Noor Jahan, there are very few words spoken out loud in the film. The song tells the entire story so flawlessly that you don’t even care that you can’t hear what is being said.

“It’s such an iconic song, and it translates to ‘if I have your one love, what else do I need from the world?’ It was inspired by a South Asian woman who came out in her 60s. And so I started thinking about all of the invisible members of our community. There’s such a big pressure to be out, but it’s such a white concept.”

We both agreed that life is so different now that we often forget about the people around us who weren’t afforded the same freedoms as we were. Culture does play a huge part of that, and it is often those in non-white communities who suffer the most or the longest. There is a lot of courage in being “out” in a culture, society or country that doesn’t see the value in your humanity. But you have to come to that courage in your own time.

“So many of our queer elders, they have to bury the most sacred parts of themselves just to survive,” Morrison pointed out. “That’s something no one really talks about — that sacrifice of living the whole expression of yourself. So I’m listening to the song and I started thinking about that woman and I thought, “man, what would that love story look like?”

Your Love begins with a grandmother and her granddaughter in the kitchen together making chai. From that first moment, I was drawn in by all of the details Morrison infused into the film. “I love my Punjabi culture so much,” they beamed. “I just drew from my life — I wanted to show a grandmother’s room,” they said, noting that there was a “warmth” to their grandmother’s home and even their mother’s home that they knew they would emulate in the film. You can feel that warmth in the color palette of the film: the deep teal of the wall, the rich mahogany of the wood furniture. The characters wear rich jewel tones like purple, turquoise and yellow. The richness of the colors shows the reverence Morrison has for their culture and where they came from

The grandmother, who is named Satwant (we never see her referred to by name in the film, but it is listed in the credits), asks for her prayer book, and in retrieving it, her granddaughter learns that her grandmother had a whole secret life she never knew about.

“I was raised by my maternal grandmother,” Morrison explained. “Fridays were special — that’s when her friends would come over. They would share stories, like juicy stories. I was allowed to sit in, and a lot of the stories were about long lost love and relationships that could have been. They would trail off like, “you know, that’s just how life is,” but I would always imagine who are the people that got away?”

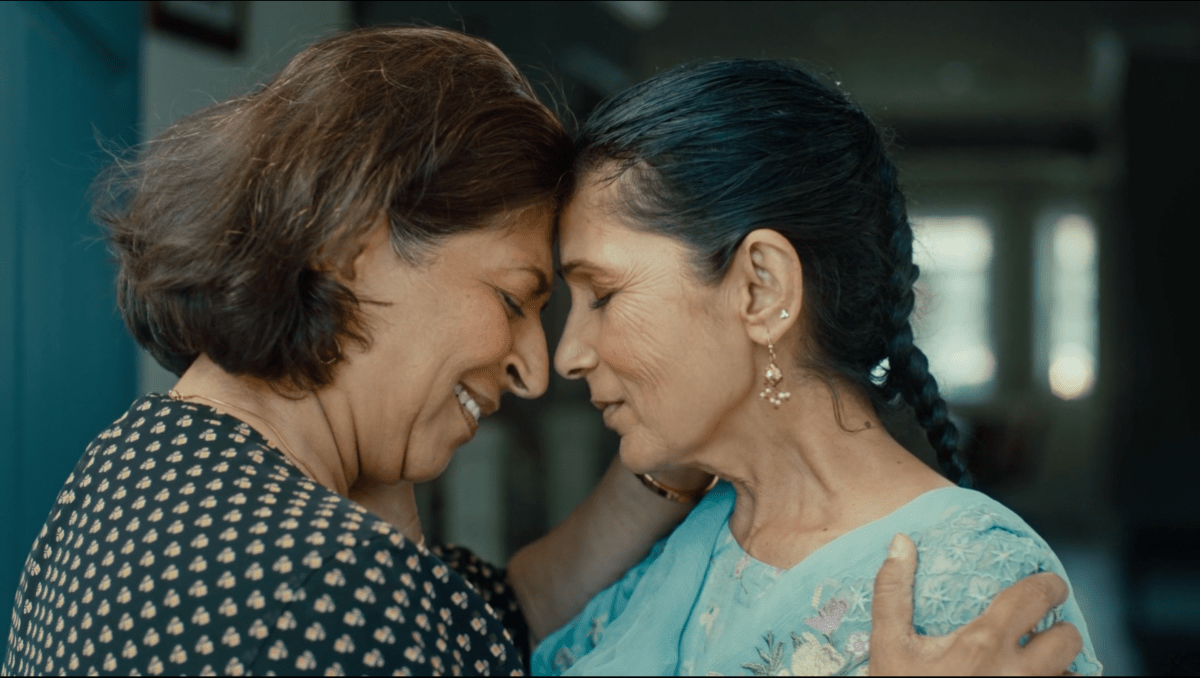

The bulk of the film acts as a flashback. We see the grandmother in her younger years. There is a young woman who she is very close to, Jasminder (again, only named in the credits) and it’s obvious that they’re totally in love with each other. They gaze longingly into each other’s eyes and discreetly find ways to hold each other’s hand. Theirs is the tenderness of young love — that all-consuming, heady obsession with just being near each other, even if the only way you can convey your love is through touching foreheads. Morrison captures the intimacy of simple touches so beautifully in these moments.

A “romantic at heart,” Morrison grew up loving Bollywood and Punjabi cinema. They had never seen “older, queer lesbian South Asian love” portrayed in the media, and so it became “important for me to show that” when it was time for them to create Your Love. And so they returned to their grandmother and her friends for additional inspiration.”One of her friends would talk about the one that got away,” they shared. The lover had a name that was gender neutral, and they explained that “it was only later that I found out that the lover she talked about was never a man, but a woman.”

The major conflict of Your Love is when the mother of Satwant catches the two young women sharing a tender moment. She flips out, and the next thing you know, we’re seeing Satwant married off to a man while Jasminder looks on helplessly. “If someone was deviating from these binaries, or had an inkling of queerness, it was like ‘we gotta marry you off right away,'” Morrison explained.

With the marriage looming, the girls get to see each other one last time (there’s that Bollywood drama!). Frantically, they talk and touch each other, relishing those last touches before they never see each other again. Satwant gives Jasminder a bracelet (a symbol of “religious iconography” that Morrison was wearing during our interview!) before tearfully pressing a desperate kiss to her lips.

I was so worried we were never going to get to see the characters kiss, but Morrison told me that it was of utmost importance for them to be shown kissing. Mainly because the Bollywood movies they watched growing up didn’t have kissing even for hetero couples, but also because they knew audiences needed the gratification of the kiss.

“Queer people have affection just like cis people do,” they laughed. “Deal with it!”

In the end, it is the granddaughter who gives her grandmother back the part of her that she had lost long ago by reuniting her with her lost love. This decision came from Morrison asking themself: “What would it look like in the world if one generation could help heal another?”

One of the many ways Morrison and I bonded was through our mutual love of our grandmothers. We both lost them when we were teens, but those relationships were hugely influential on who we are as people. I asked Morrison if they ever came out to their grandmother, and while they didn’t say the words, they believe she always knew.

“My grandma was the first person to see me fully,” they explained. “We would go to temple every Sunday, and that walk to the altar felt like a death march sometimes. You had to present in your Punjabi suit and be a proper Indian girl. There was this one auntie who would constantly pick on my attire; I was never wearing the right thing or saying or doing the right thing.

She says to my grandmother, “you have to do something about her,” and my grandmother says “about what?” And she’s like “she walks like a boy” and I remember feeling so embarrassed. My grandmother looked at her and said “So what of it?” That auntie ended up leaving and my grandmother turned to me and said “Shiva has a male and female form. We all have that. There’s nothing wrong with you.” and it was that moment that stuck with me.”

That story stuck with me too.

Would love to watch this, thanks for the review!

you can watch it online as part of the Outfest virtual programming! the other shorts look awesome as well.

https://watch.eventive.org/outfest2023/play/6493865286a854002ca7bf73

Wow, this sounds really wonderful. Thanks for highlighting it and letting us into the interview!

Where can I watch this?! This looks incredible!

you can watch it and the other shorts it screened with here!

https://watch.eventive.org/outfest2023/play/6493865286a854002ca7bf73