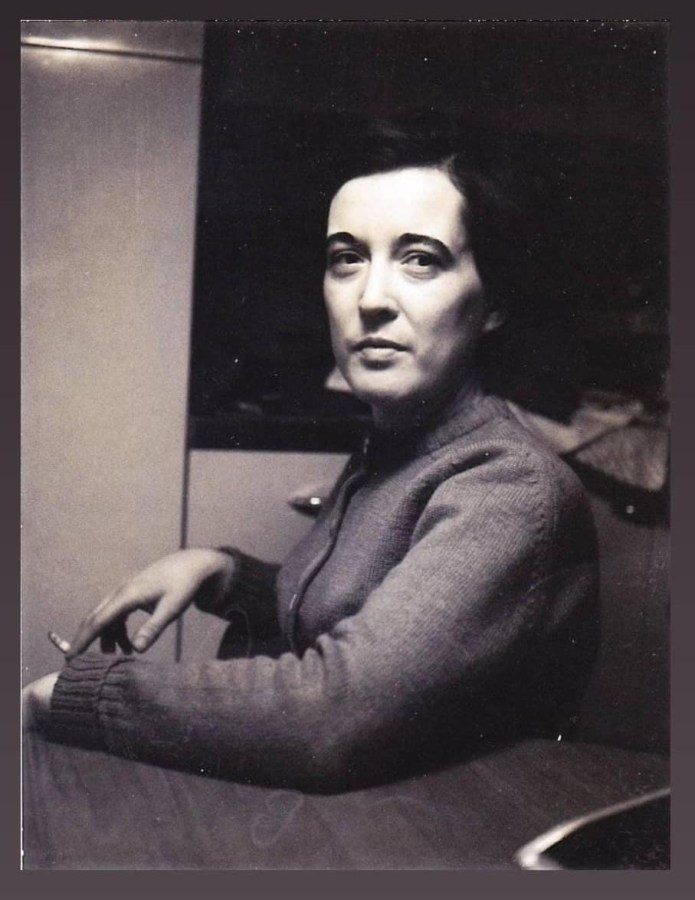

I’ve been eulogizing, just to myself, in the moments between other moments that are claimed by tasks or thoughts of the present or literally anything else. But in the minute or so before the kettle boils, after the bag and honey are in the cup, I’ll stretch my mind back to the days when staircases were mountainous and I was still learning the names of birds.

My grandmother cared for me a lot when I was young, in those pre-Kindergarten years. My grandpa was alive then, but in his final years, so spent most of his time either at the kitchen table with his oxygen tank or on the living room couch with the same. So, that left my grandma to amuse me — and to our delight, we made excellent companions.

I had a hunger for exploration and, even at that age, would happily walk for long periods (for a child of three or four). This meant we spent countless hours just walking places, including around the quarter mile path in Buffalo’s Delaware park where I’d balance on the old cobblestone curb that bordered the grass, playing an endless game of not getting eaten by crocodiles. I’d accompany her on errands, to the cobbler or to the deli. On special occasions, she’d take me to a museum or to the zoo, where I turned to her as the holder of All World Knowledge and asked about everything from why there were so many naked ladies in the art museum to why the “Lucy” skeleton of an early human in the natural history museum was my-sized if she was an adult.

On the most special occasions, we’d go to the cemetery where we’d look at the graves and feed the ducks. At one point, on one of these cemetery visits, my grandma had picked up what might have been a guide pamphlet at the main office, and read to me aloud the story behind a particular mausoleum featuring a sculpture of a young man in repose with an angel above him. He lay with one hand on a Bible on his chest and his legs crossed in a number four shape. The angel, apparently, had been a maid, Katherine, he’d been in love with whom his parents forbade him from marrying and who they fired after sending him to Europe. When he died after a lingering sickness he contracted upon his return, clutching the Bible Katherine left behind, she supposedly became the inspiration for the angel above him, perpetually welcoming him into heaven. Did his rich parents ever do right by the maid they fired who became the model for an angel in their son’s grave? Probably not. I know what I did do, though, which was decide, in my childish superstition, that the best way not to die in my sleep was to sleep Exactly Like This Man. When we returned, my grandpa joked with me that a ghost had come by looking for me.

And why did I have such an intense dread of dying in my sleep? Well, because when I would kneel with my grandma during those days, at the edge of her bed to say our evening prayers before we crawled in and slept next to each other (my grandpa slept downstairs), we’d recite:

As I lay me down to sleep,

I pray the Lord my soul to keep;

And should I die before I wake,

I pray the Lord my soul to take.

When I asked her about it, she explained exactly what it meant: that we were asking for safe passage to Heaven if we died in our sleep. This, naturally, presented me with the concept of Dying In My Sleep, which would plague me for most of my early years in one way or another. I slept like that man from the mausoleum for years to ward it off. For years!

I always knew my grandma was intensely aware of her mortality, of my grandpa’s, of mine, of everyone’s. It threaded itself through our conversations and our days together. Thanks to her, I learned early on what a DNR was, that she did not want to ever be kept alive by artificial means past the point of having agency. She was born during the Great Depression, lost a brother as an infant, lived without indoor plumbing in the Polish neighborhood in Buffalo, practiced Air Raid drills in World War II, and lost countless people — in all kinds of ways — along the way. My grandpa was also in the process of dying at the time and would pass by the time I was in the 1st grade. It had to have been heavy on her mind.

Last week, I drove through a wintery mix in my old Subaru up to Buffalo to see her for what might very well be the last time. As I approached my grandma’s bedside and my uncle woke her up, I had a feeling — despite the many “she probably won’t recognize you” warnings I’d received from my mom — that she would know me. Her eyes opened. I said, “Hi, Grandma.”

“What are you doing here?” She looked at my face and held my gaze. The question was bewildered — I didn’t live there! But it wasn’t unkind, and it was steeped with recognition. I told her I’d come to visit her, that I loved her. It’s hard to remember what I said, trying to have a moment in a room that’d become crowded with my uncles, my mom, my sister. My mom had put out a blast that I was coming up, so all of my grandma’s children were present to see me see her.

But here’s the thing. I think, on some level, I do really see her. When I was 13, I lived with her during the week for most of a school year. My dad was deployed, and my mom had decided it would be easier on her because of my after school running practice and such if I just stayed with my grandma who could drive me around or whatever. I’d pack up my bag and stay in a little spare bedroom where the entire wall next to the bed was a bookcase, stuffed with my grandma’s reading material. For most of her life, she was a voracious reader, and she certainly read the classics. A hardcover copy of Crime and Punishment sat in her living room at all times. But she liked the pulpy stuff, too. I distinctly remember her reading the entirety of The Girl Who Kicked The Hornet’s Nest series, as an example. I’d pick through her books, read them, know the things she had read, devouring some of the more scandalous books in secret. She didn’t speak down to me even when I was younger, just addressed me with a matter-of-fact tone that complimented my early grasp of language and child’s curiosity. As a kid, I was considered odd, except, looking back, I fit the mold of “The Little Professor” quite well, which would have suited her, someone who I suspect was and is also autistic.

When I lived with her as a teen, I noticed some things that stood out. She kept to a breakfast schedule, for one. Each day of the week had a specific breakfast she would prepare and eat on that day. She repeated this infinitely but still had it written on a leaf of paper she kept square to the edge of her kitchen counter for reference. She was particular about her routines, and I remember her quitting her book club because no one read the whole book and they “just wanted to chit chat,” which, valid.

Our connection, and the reason I pissed off my uncles for years by occupying the status of favorite grandchild over their kids, was one of neurodivergents who just kind of “got” each other, whether or not I grew up to be a gender-nonconforming tattooed bisexual. And in a lot of ways, I have my grandma to thank for the ways she showed me how to navigate the world, and this meant — often — with a kind of quiet disobedience, a distinct and singular approach to claiming the right to plan her own journey, even with whatever limits her life placed around her. She mythologized this part of herself, too, telling me stories about being a trendsetter; “When I started smoking, everyone[referring to her sisters and mother] decided it must be okay [for women to smoke], and they started smoking, too,” and “When I started wearing Tampax, everyone started wearing Tampax” are just two small tales from her vault.

When she found out the local state college was free (at the time), she decided she was simply going to attend because why not? She wanted to and that was always a good enough justification for her to do something. I still have the typewriter that her father bought for her off a fellow barfly while bragging about his daughter who was the first in the family to go to college at his usual nighttime haunt. She was conversational in Polish and told me stories from the neighborhood, like about how every man who came into the card shop she worked at with my grandpa’s parents got two gifts on Valentine’s Day, one for the wife and one “for the sweetheart.” She seemed unperturbed by this reality. It just was. She told me about the first time she painted her nails red and walked, head held high, through Buffalo’s Polish neighborhood while older women hissed at her and said “Devil, Devil!” when they saw her crimson-tipped fingers. And though she dropped out of college the first time, she returned, much to my mom’s dismay, at the same time she went, and to the same school where she fought with an advisor who told her women didn’t study history. She won that fight.

She also had a temper, was inconsistent in many of her narratives, and, ultimately, needed my grandpa’s help getting a job because she was so notoriously tactless that she couldn’t do so on her own. She would scoff at sappiness, unless it was directed at her. She could be hurtful without meaning it, through her bluntness. I remember being nine or ten or so, having drawn a self portrait that was on display at some school art show situation, and her remarking, “Hm. That doesn’t look like you.” Which, sure, 10-year-old me wasn’t going to be Michelangelo, and I am sure, factually, it was not an accurate representation of my face, but is that what you say to a kid? But even this, her just existing and saying the wrong thing and going on living, was a lesson.

Her approach to taking up space as herself, to finding her own company agreeable, to not needing to bend to other peoples’ will had my uncles, when I visited, calling her A Great Lady. It was an odd homecoming, reminiscing about her by her bedside while she lay there dying of a combination of a long battle with dementia and a recent fall. It’s been years since I’ve seen these uncles, for various reasons. I watched them be humans, grieving — whether that meant trying to hold a normal conversation through tears, insisting that my grandmother should still take her vitamins (for what?), or kind of dissociating and ignoring the Great Lady in the room to chat with me.

One thing I heard over and over again was that before the fall, one of the things she had still loved to talk about were the early days with me, our trips to the park, our walks and the fun that was just between us. I remembered that from when she could still do phone calls. I knew her memory was going, pre-pandemic, and so when I called her to say hello sometimes while walking to work in the morning, I’d just talk with her about the past. It kept her more engaged than the present, was more hard-wired in.

As I drove my sister back to her place where I was staying, we agreed without hesitation that our grandma probably hates this current state she’s in, that if she’d had a proper say, she would’ve chosen euthanasia. “She always said to pull the plug!” We talked about family dynamics, about how hard it was on our youngest uncle, clearly.

I visited her again on my own the next day, with only an aid, a family friend and a nurse out on worker’s comp, present (so no circle of uncles this time). I helped the aid get my grandma up and to the toilet, as well as into her wheelchair so she could go sit in the living room and have an egg and some Boost at the table. I sat talking to her for a while, and she recognized me again, this time saying nothing, but glancing around my face with her eyes. The aid gave me some time alone with her, and I said a real goodbye, told her how much I loved her, reminded her of our times again, knowing she could still hear me, even if she didn’t respond.

While my grandma was asleep, the aid told me she hoped my grandma passed soon. We’d built up a rapport that afternoon, and she told me why, that my grandma talked in her sleep when the aid was there, and that recently she’d just said, plain as day, “I just want to die.”

I said I knew that, talked about how she always talked about her DNR. She was clear, but there was nothing we could do. I said I hoped she felt like she could let go soon, now that all the family had come through.

And I drove home, back to Pittsburgh, thinking about her and the influence she had on me, on the ways she encouraged some of my more antisocial tendencies, for better or for worse. I still smile, when I think of her rocking me back and forth in a hammock one summer night, when she said, as we complained together about being annoyed by other people out in the world, “A wise man once said, ‘Hell is other people.'”

This is a really beautiful tribute Nico. Thank you for sharing it with us <3

Gen, thank you so much <3 Thank you for reading.

This touches my heart. Thank you for this beautiful piece

KatieRainyDay, thank you 😭

your grandma sounds awesome Nico, thank you for sharing her with us <3

Sai!! That means so much. Thank you! 😭

Beautiful piece! I’m so happy you and your Grandma had such an amazing connection.

Thank you for sharing your beautiful memories and stories of her. Kid-me likewise developed a bit of a thing about dying in my sleep after people talking about (elderly) relatives doing so, and hoping “that that’s the way I go”. Nobody explained that spontaneously dying in your sleep is pretty rare in younger people, so it just played over and over in my anxious little mind!

Such a moving piece. A Great Lady indeed. ❤️

Ao explorar o Mostbet PT , fiquei encantado com a diversidade de jogos disponíveis, tornando cada sessão uma jornada cativante. O aplicativo móvel proporcionou uma experiência imersiva, enquanto os bônus atrativos aumentaram ainda mais a diversão. Recomendo vivamente o mostbet-portugal.bet a todos os entusiastas de jogos.