Best Films of 2023 lists have been filled with art that grapples with the genocidal actions of powerful men. Oppenheimer, Killers of the Flower Moon, and The Zone of Interest attempt — with various degrees of success — to display the mundanity of large-scale violence. From the atomic bombs to the assassinations of Osage people to concentration camps, the killing is meticulously planned. And yet each film shows how little the perpetrators of this violence reckon with their actions — at least until it’s already been done.

Unfortunately, these works of history remain relevant. The same justifications of greed and fear have motivated Israel’s latest U.S.-backed escalation of violence against Palestinians. Meanwhile, here in the States our cruel immigration policies and prison system steal millions of lives. Few people carrying out these modern atrocities connect their actions with the actions of the past. People take what they want from history and rarely see themselves in the villains.

There is an undeniable power to Oppenheimer, Killers of the Flower Moon, and The Zone of Interest, but there’s also a limit to their depth. What do they reveal about the evils of men? They are artful, emotional documentation, and there is value in that. But the only film I saw this year that really confronted the perpetrators of this kind of violence was a four and a half hour documentary from 1976, Marcel Ophuls’ The Memory of Justice.

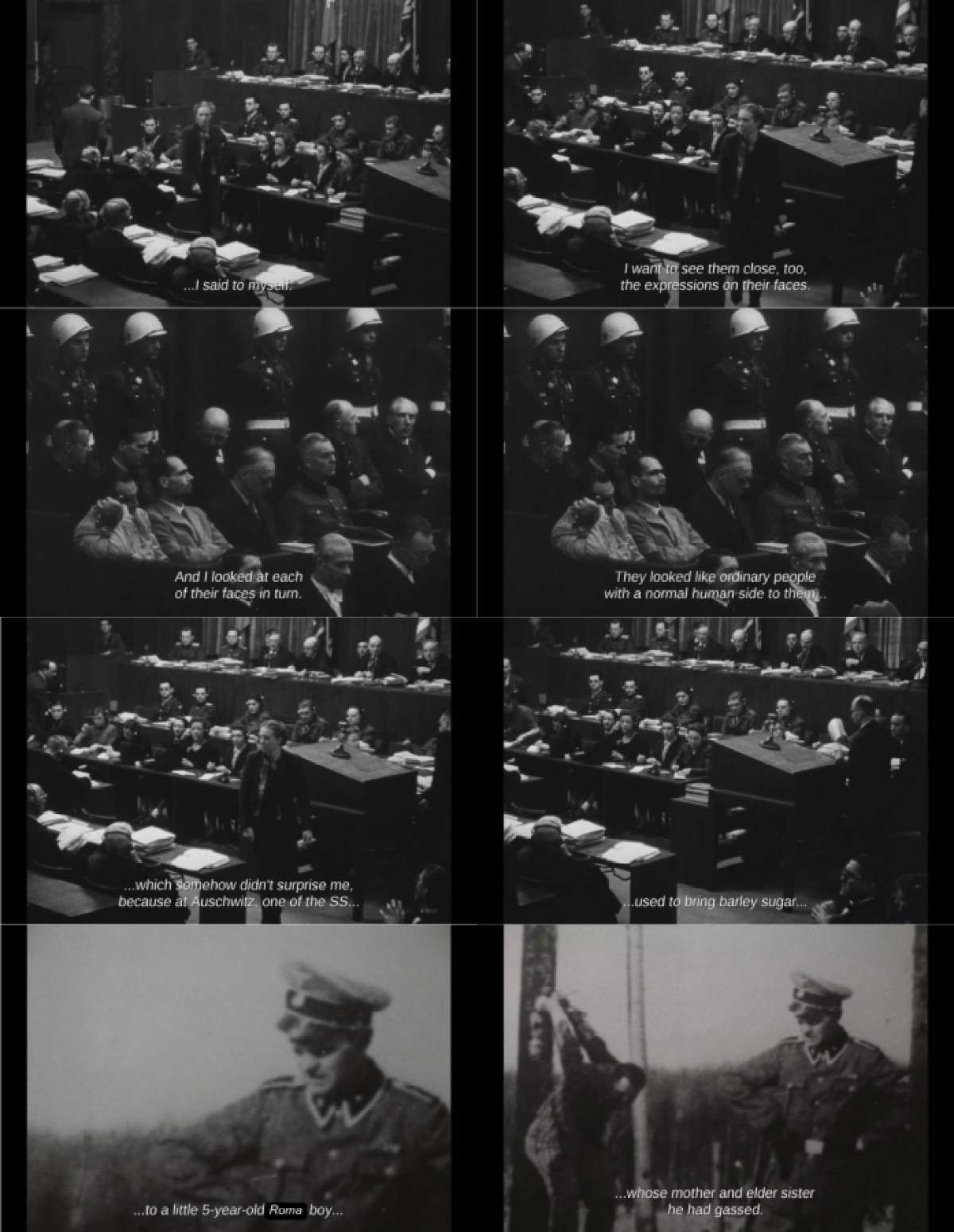

Unlike Ophuls’ more famous Holocaust documentary The Sorrow and the Pity, The Memory of Justice does not allow its continued relevance to remain subtext. It’s one thing to say we must study history so as not to repeat it — it’s another to place past and present side-by-side. In The Memory of Justice, Ophuls focuses on the Nuremberg trials and the continued reckoning within Germany. But he wisely acknowledges there is nothing uniquely evil about the Nazi regime. The film draws parallels between the Holocaust and the more recent horrors of the French occupation of Algeria and the American occupation of Vietnam.

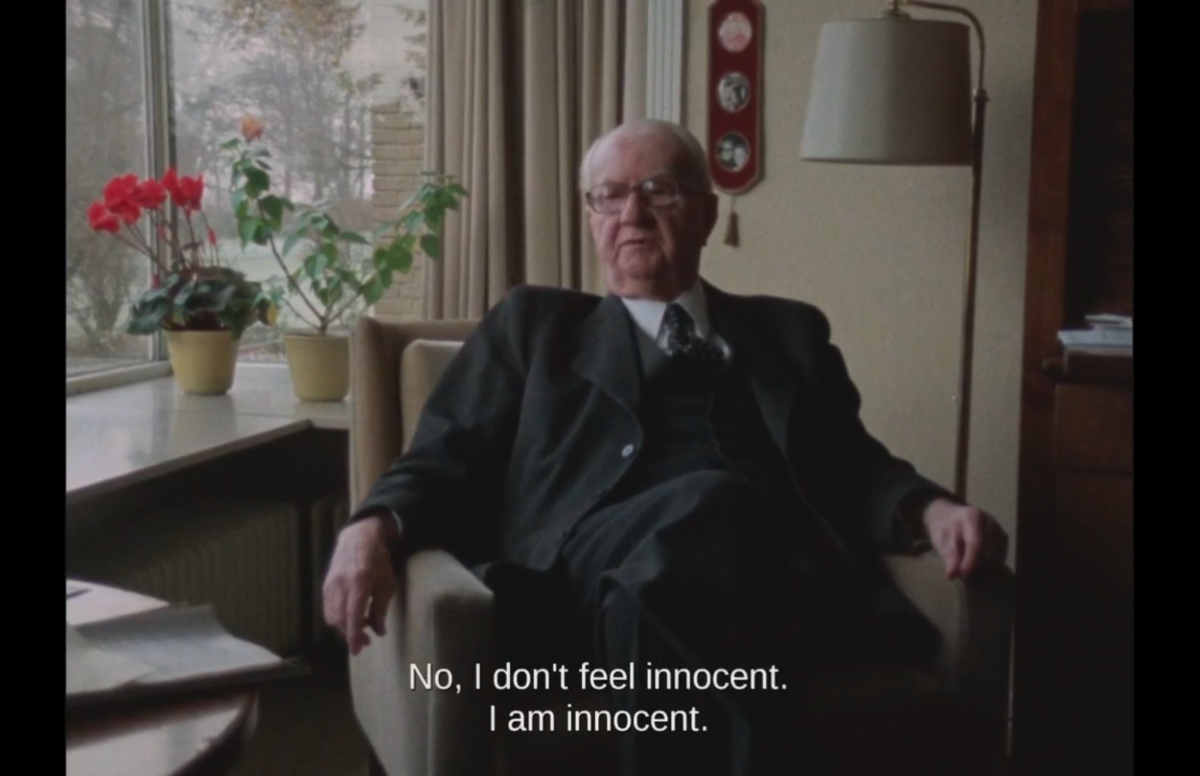

The Nazis who Ophuls interviewed use the same excuses and justifications that people use today. One Nazi refuses to admit he was ever antisemitic. Another Nazi understates the suffering at the concentration camps because “at a camp you can walk around when you like and where you like.” Other Nazis claim to not have known the scope of the violence. Even Albert Speer who notably admitted responsibility and spent his life supposedly atoning is unwilling to admit the entirety of his role. His narrative of himself as the good Nazi, the apologetic Nazi, is just as self-serving as the Nazis who deny their guilt.

The film is very explicit about the atrocities of the Holocaust. It also questions why the Nuremberg trials focused on the German actions alone. What about the bombing of Dresden? What about the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki? Only the losers of war are forced to answer for their crimes against humanity.

Calling political opponents Nazis is seen as cheap and dramatic. But this film highlights the validity of the comparison. The United States and France have carried out many holocausts, and have been led by people who acted like the Nazis. To truly reckon with the Holocaust is to remove the evil from its pedestal and recognize it as common.

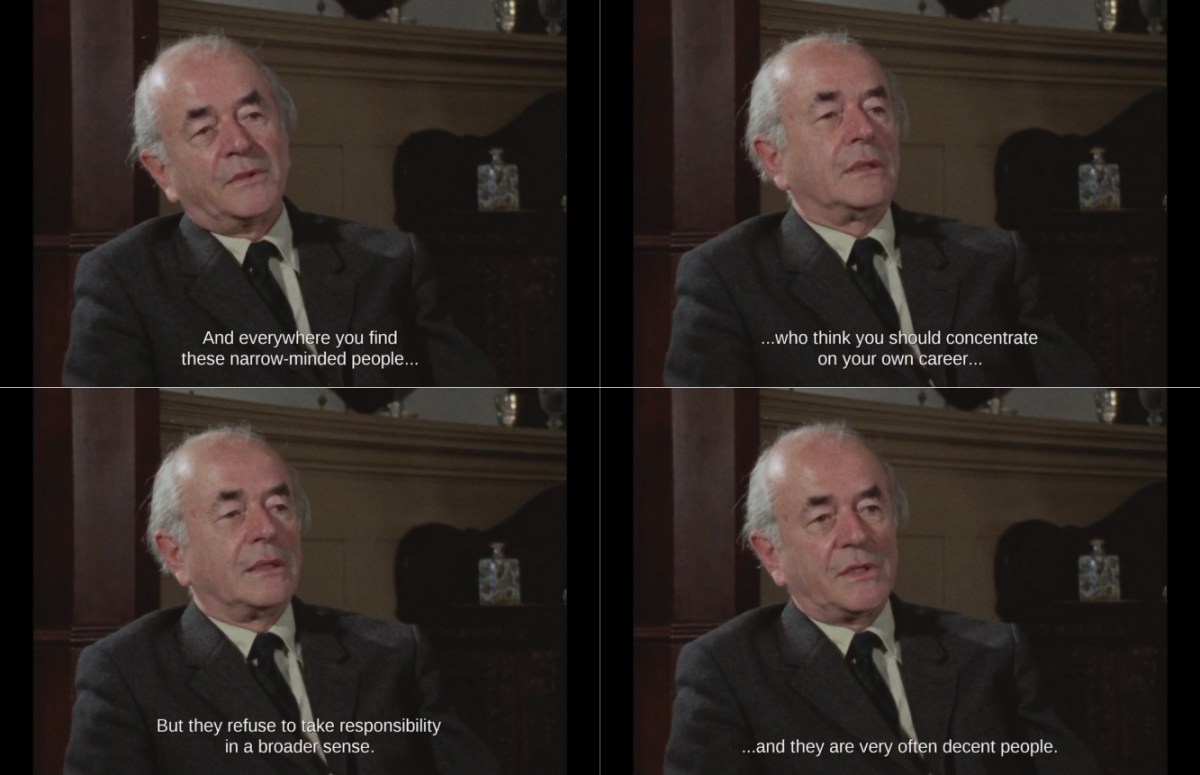

Daniel Ellsberg, who leaked the Pentagon Papers and revealed the extent of the U.S. evils in Vietnam, makes one of the film’s most frightening observations. He notes that within the Pentagon Papers there is no debate about ethics or legality, only practicality and effectiveness. Amorality is more frightening than immorality.

Showing evil on-screen — in narrative or documentary form — is not enough to stop it. But the clearest work, the most impactful work, uses history to confront the violence of today. We need more media like The Memory of Justice that excavates the past without allowing people to dismiss or misinterpret its relevance.

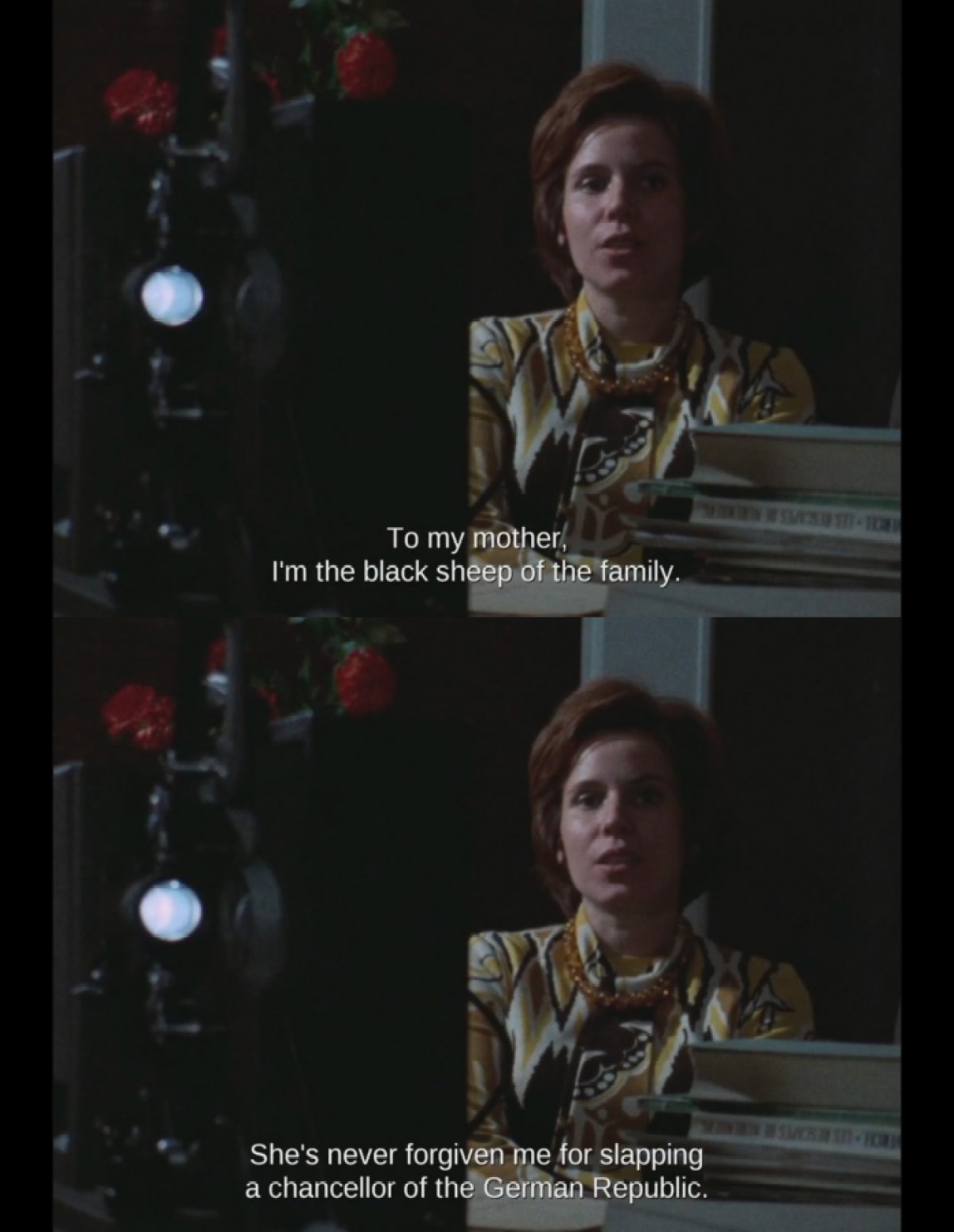

“No more genocide in my name,” a woman sings during a protest at Kent State. Watching this, my stomach dropped. I’ve heard that said so many times over the past few months as American Jews plead with our politicians to stop funding Israel’s violence. It’s easy to feel despair at this endless cycle. But there’s also inspiration to be found in the parallel history of resistance.

The Memory of Justice makes it clear that the greatest perpetrators of violence will never acknowledge their villainy. But we can acknowledge it for them. We can refuse the easy narratives of the powerful and fight for a world where human life — all human life — is valued. We can fight for a world of true justice.

The Memory of Justice is not currently available to stream.

Going on my list of films to watch!

It was restored by the Film Foundation so I really hope it’s made more widely available soon!