The LGBTQ Outdoor Summit, sponsored by REI, took place from April 1-4. This article was created in partnership with REI. Interviews have been condensed for clarity. Photographs by the author.

“Find community wherever you can and treasure it.” — Megan E. Springate (she/they) at the LGBTQ Outdoor Summit

Over the first weekend in April, the LGBTQ Outdoor Summit convened, for the first time in two years, on the ancestral homelands of the Shawandasse Tula and Massawomeck people (near Shepherdstown, West Virginia) at the National Conservation Training Center. I’ve lived in “the Paris of Appalachia” for the past six years, but I hadn’t had the opportunity to visit this part of West Virginia. I was excited and ready to connect with queer people and learn about our community’s work in the outdoors. To be honest, though, I was anxious. It would be my first time in two years being at an event this large, and it was only 65 people.

I navigated the rolling hills and twisting roads on the way to the center, my anxiety sitting next to me in the front seat while locals tailed me and I tried not to miss my turn. As soon as I got there, though, the organizers and employees of the center welcomed me and made sure I knew where to go. The organizers handed me a schedule of the events: salsa dancing that night, presentations on Saturday, and a Sunday dedicated to spending time outdoors and making connections. On my way to dinner on that Friday afternoon, a bald eagle flew over my head, the first I’d ever had come that close to me in the wild. The yellow of its feet shocked me to see in real life; the color was brighter than I thought it’d be. While walking across the campus, I exchanged smiles with my fellow Summit attendees. For a brief moment in time, we were about to fully inhabit this space, to make it our home away from home, each of us a part of a temporary but powerful queer community in the woods. It felt safe to be there.

That safety means a lot, especially with the wave of anti-LGBTQ legislation introduced by legislators across the country. At this summit, conversations around making outdoor spaces safe for queer and especially trans people, and trans people of color and youth, were front and center. REI and several other companies have spoken up to support LGBTQ rights in the face of this anti-trans and anti-LGBTQ legislation. REI has also reached out to their employees and members about supporting the Equality Act. By speaking directly to their members and showing support for their LGBTQ employees, REI is using their platform to materially make a difference. I hope that we continue to see visible action on the part of companies like REI, both in condemning anti-LGBTQ bills, and as leaders in the outdoor recreation space, including external donations and internal support for employees. It’s important for recreational companies to use their platforms to speak directly to their customers about inclusion, especially because their customer bases include many of the people that queer and trans folks share space within the outdoors.

After dancing that first night, we gathered in front of a fire, some of us talking about the stereotype of “outdoorsy lesbians.” It is a stereotype for a reason, as there is a real history of queer people escaping to nature to be themselves. On the other hand, it’s deceptive because there are so many barriers the LGBTQ and marginalized communities face when trying to access the outdoors — transport, finances, knowledge, time, accessibility, safety and more. Summit attendees were there to talk about and address those barriers, or to form connections to help them do so in the future.

I met some younger participants who’d spent two of their early adult years in a pandemic. Some had never gathered in an intentional LGBTQ space. One person told me that they weren’t out at home, but that here, they could be themself and no one would bat an eye. It was overwhelming, and it was like coming home all at once.

Saturday

On the first full day of the summit, Cimmaron Craig (he/they) helped set the tone for the space. The event organizers, Elyse Rylander (she/her) and Hannah Malvin (she/her), hoped that for this iteration of the summit, we would be able to focus on cultivating connection and finding joy.

Throughout the pandemic, in my role as Membership and Fundraising Director, I’ve poured myself into trying to keep Autostraddle around, draining my well and staying, too often, glued to a computer screen, ignoring my need to move my body, to be in nature, to connect with others or myself. I’d been an out member of the LGBTQ family as a bisexual for a long time, but I came out, again, as nonbinary/genderqueer/trans in February of 2021. Because of the pandemic, I hadn’t had many opportunities to celebrate my identity with queer people other than my partner or a few close friends. I hadn’t been able to let myself think about my own journey — I had to stay focused on what other people needed from me. When Cimmaron invited us to close our eyes and breathe together, I felt one hot tear fall down and dampen my mask. It isn’t easy to give yourself space for joy, sometimes, when you’re not used to it, because that means that you have to acknowledge how long you’ve gone without. I know I wasn’t alone at the Summit, in finding joy being a challenge — I wasn’t the only one with tears in my eyes — but we made space for joy nonetheless.

Jessica Manuela Loya (she/her/they) was the day’s keynote speaker and generously gave me some of her time. Jessica lives and works in Washington, D.C. where she wants “to make sure that LGBTQ leadership in the outdoors is a part of the national narrative… when it comes to [national] policy.” They told me, “The fact that the theme is joy and connection really shows that just as much as it is important for us to advocate for ourselves for the improvement of everything around us for our lives, for future generations, it is also important to take space and laugh.”

Jessica Manuela Loya

“I don’t think that I, before this, ever felt like I connected to the LGBT community because I had worked in and prioritized my identity as a Latina. And I had not, at least as an adult, found the spaces where I could be with the LGBT community and to find them where all of my love connects — my love of nature, my passion for the outdoors, my love of community-building — to find it here is incredibly gratifying, and it makes me hopeful for my future. ”

When I asked Jessica what the summit was like for her she told me, “I think to be loved and seen in a larger community as a queer, outspoken woman of color, to feel ‘safe’ is,” they paused, “I could not have asked or needed anything more than this after what has been some very turbulent earthquake years in my life.”

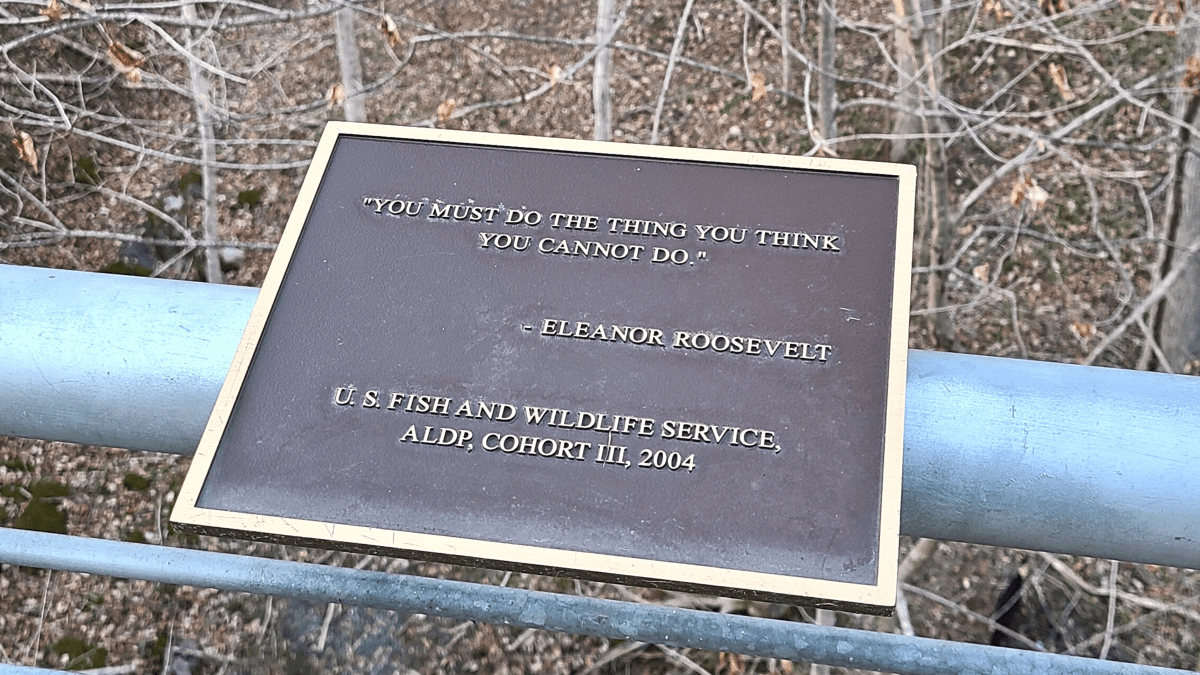

Another person I spoke to, Ollie Zanzonico (they/them), came to the summit representing the Pride Employee Resource Group at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Like Jessica, Ollie is a part of the work queer and trans people are doing across the country to make outdoor spaces more welcoming for everyone.

Ollie Zanzonico

They asked, “how can I do this [provide community like that found at the summit] for other people?… Like, this is really meaningful for me… and I can’t imagine, well, I can imagine, somebody else who still needs that community and needs that connection. How can I do that for them? It’s hard. I feel a lot of pressure because I feel it’s so important.”

Ollie shared, “I think a lot about why queer people don’t feel comfortable in outdoor spaces — and it’s not just any one thing — it’s a whole really overwhelming systemic structure. Certain culture and conservatism and old-fashioned beliefs that exist in some of our most beautiful places that also have this really dark history or a really dark side to them…When we talk about diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives that we’re pushing in the Fish and Wildlife Service [we ask] who is America? Who are we serving?… I just want public lands to fulfill their mission, to serve the public — and that’s everyone.”

The LGBTQ Outdoor Summit brought me so much hope for what’s next for queer people in the outdoors, because of the people working on queering outdoor space in all different ways, from government policy, to volunteer outreach, to people leading youth groups, to someone hiring queer people, one by one, for a backwoods carpentry crew.

On Saturday afternoon, Hannah Malvin (she/her) interviewed Megan E. Springate (she/they), editor of the LGBTQ Heritage Theme Study. The first of its kind and a project of the National Park Service, which brings together peer-reviewed writing by experts in LGBTQ studies, writing on place-based LGBTQ history. Megan told summit attendees, “It’s important to push back against people who say, ‘This is the way we’ve always done it.’”

Pushing back against that ‘way we’ve always done it’ mentality is a huge part of making outdoor spaces more inclusive, according to Neak Loucks (they/them). They’ve worked in conservation for the past three years, and in line with their dissertation, are interested in finding and helping to create queer community in conservation and the outdoors.

Neak Loucks

“I think that there are a lot of people in that space who have a lot of good intentions. And I think [they] are not always used to receiving feedback like ‘oh that you might not know how to make a space inclusive for someone of X identity.’”

“Wilderness, for example, is a cultural value and it’s a social construction. and the creation of wilderness spaces in the United States is premised on the removal of Indigenous people. So that’s one of those cases where you can have tension between people wanting to be more inclusive, wanting to incorporate Indigenous perspectives, but then their own idea and value about wilderness can come up against, like ‘oh if you want to be more inclusive, you kind of have to interrogate that history’… As a queer and trans person in the conservation space, it has definitely been a process of educating people.”

When I asked Neak what they were taking from the Summit, they said, “The power of seeing people having those little pockets of work, because sometimes it seems like you’re barely moving the needle, or your change is so small it can be disheartening, but the reality is that is the nature of how people learn and change and grow.”

“Maybe I’m only getting four shovel-fulls of change per month, but I know this person over here is doing the same kind of thing in that space, but that is heartening because it’s like okay we all have shovels.”

This rang incredibly true to me and my role when I am leading initiatives and asking for collective action on the part of our readers at Autostraddle. I often say that we don’t have to do it all when each person does a part.

Hazel Platt (he/him or they/them) attended the summit representing the Pacific Crest Trail volunteer program and spoke about the value the event held for him. He shared, “I feel like it’s often very lonely going to work, and just being like, ‘oh I am the only out trans person at my organization.’ And I’m often working with volunteers — working with a lot of people that might not have any clue about any queer issues and things like that — and it can be really hard to feel like I have to be so vulnerable all the time. I put my pronouns at the end of my email signature and send emails out to lists of 10,000 people… It just can feel like a lot some days. So just to feel like, okay, there’s all these other people doing this thing and pushing for equity and pushing for more queer people in these spaces. It just feels a lot less lonely.”

Scout (they/them), who is a backcountry carpenter, builds and maintains structures on long trails. They, too, spoke about queering the outdoors in their everyday work life.

Scout

“I’ve been intentionally trying to shift that [the feeling of being the only queer/trans person in an outdoors space], not just by being in that space… and more like, creating invitations, opening the door for somebody. Being like…’I want you to know that I will be here to be another queer person that you can see doing this work and hopefully you can explore it and thrive.”’

“One of my crew workers is returning from last year who is also queer and trans and it’s just like, that feels so good. Because it’s mostly them making that choice, but I’d like to think some of it was because I was very intentional about making it safe for them to be in the outdoors… I’m so just ecstatic, like I’m over the moon that they’re coming back… I just want folks to feel like they can do this work and feel in community simultaneously.”

Sunday

On the second day, I ventured into the woods on a nature walk led by Sean Binninger (she/her). Sean showed us how to identify certain bird species and we all watched through binoculars while a woodpecker pecked away for insects in the wood of a dead tree still teeming with life. We came across a patch of white flowers, and though someone identified them as twin leaf plants, Brian (he/him) remarked that he was hoping they were bloodroot. He told us about the Bloodroot Cafe in Connecticut, a lesbian-run cafe and bookstore in operation for over 40 years. He talked about visiting in the 70s (or 80s) and told us that he “dined on hearty food and rhetoric” which got a few chuckles from the group. It was one of those moments of being in an intergenerational queer space, and one of collective learning where that truly resonated with me.

Hannah told me, “One of my favorite parts of working in building queer community is the intergenerational piece… it can be fascinating and powerful and moving and intense and special to learn about one another and to learn more about how you fit into this larger community and its history and its evolution.”

Hannah Malvin

Among the conversations about increasing access to nature, everyone I spoke with brought me a story about the healing nature of… well, nature!

Neak told me, “I think about the ways in which being in natural spaces is actually an early space of connecting with my experience of gender… My hope is that through engaging in building queer outdoor community, helping others become more aware and change their behaviors, that more queer people have more ability to tap into that joy.”

Hazel said, “The outdoors has been profoundly healing. Being able to go out into the woods for an extended period of time has been a way I’ve gotten through some really tough stuff in my life.”

Their words brought me back to being a kid, myself. In the early years, I lived in a rural area, and ‘play was so often disappearing into the outdoors in the morning, coming back for lunch after walking for hours through the woods along an 18-mile creek, play-acting or spotting red-tailed hawks in the trees. Now, I am starting to see how spending so much time outside in my childhood fought some of my dysphoria or fear around being queer or nonbinary. Spending so much time outdoors gave me a sense of being a natural being, of having a place under the trees and the sky.

Christopher German (he/they), who’s worked in the queer youth outdoor space, said “To me, the importance of queer youth being in nature [is] seeing that nature is also queer, and understanding that they are natural, and that there’s nothing wrong with them, or any mistakes that were made on them.”

Luke Warner (he/him) is a trans man and Association of Nature and Forest Therapy certified nature and forest therapy guide. We talked about how research actually does prove that access to the outdoors can heal. Luke said, “I started looking into research because I studied risk for my master’s degree. I was really interested in the ways that nature interventions and connecting with nature could be… used in a way that could alleviate some of the main things we [LGBTQ people] are at higher risk for — things like depression, anxiety, attention disorders.”

Luke Warner

There were a lot of times that we talked about not just the queerness of nature, but also the value of its lack of scrutiny. Luke said, “Those things outside are really not interested in me or my identity. They will keep going, regardless of how I identify and who I am… these birds here will keep doing their thing, and that can actually be a really validating and calming experience.”

Earlier, I named some things that companies can do to help the LGBTQ community increase accessibility to the outdoors and in work in the environmental and conservation sector. I want to emphasize that when REI and other outdoor companies directly support LGBTQ-led organizations and events, such as The LGBTQ Outdoors Summit and other LGBTQ-led organizations in the outdoor space, these companies are demonstrating that they understand that it’s important to trust LGBTQ leadership to know what’s needed for our community. If you’re a company (or an ally) the best thing to do when considering access and equity in the outdoors is to support the people who are already engaged in this work and activism, especially leaders who are Indigenous, Black, people of color, queer, trans, who are women, and who hold more than one of these identities.

There were more connections and more joy this weekend than I could begin to contain in a single article. Even on a personal level, I left feeling recharged and confident in my ability to find a way to feel at home when next I ventured outdoors. In fact, I went camping my girlfriend and our dog this past weekend. After a long winter, my body had forgotten how deeply healing it is to be among the trees, under a full moon, away from cell phone signals, away from demands on my person. Still, in an attempt to capture the vastness of these feelings, I’m going to close with some words from Jessica and Scout.

Jessica shared, “I hope…that LGBT communities all over the country…know that they are welcome and they are worthy of all of the love and joy and connection that comes with being in a community like this but also going outside and standing in the sun.”

Scout said, “I hope other people see the invitation [of this article] like, hey, maybe…you thought you were the only one, you’re not. We’re here and we’d love to have you so so much…There are people working diligently to make these spaces safe and welcoming for all of us.”

So, if you’re hesitant, I also hope that now, at the very least, you know some of the queer and trans people who are out there — in the outdoors, working for you, inviting you, waiting for you.

They, and I, hope you will.

As I reflect on the conversations I had with fellow attendees at the LGBTQ Outdoor Summit, and some of the experiences they shared with me, I wanted to speak to a few notes on creating safe space when engaged in queer community-building:

- When you’re in a space, consider who you’re choosing to connect with and who you are not. Question if you are not engaging with someone because their identity is different from yours. If you’re in a position of privilege, challenge yourself.

- Don’t assume anything about someone else’s pronouns, gender, or trans status.

- Interrogate dominant frameworks! Part of queering the conversation is checking (and queering) your sources, especially if those frameworks were established by cishet white men.

- Keep accessibility at the forefront, not as an afterthought. Always design with accessibility from the ground up.

Opportunities and Resources

Join REI Co-op in urging Congress to pass the Equality Act and finally extend federal civil rights protections to the LGBTQ+ community

Sign up for Pride Outside’s newsletter.

Volunteer virtually with Stonewall Rangers.

Join the LGBTQ Affiliate Appalachian Trail Crew in 2023.

Read the entire LGBTQ theme study online.

Connect with mentoring and job opportunities through The Bridge Project.

Watch the Patagonia film, They/Them: One Climber’s Story. Read Abeni’s interview with Lor, the climber and central figure of the documentary, for Autostraddle.

Nicole, thank you so much for bringing this to us. As an outdoor queer who didn’t grow up seeing a lot of people like me outside this is fascinating. I’ve definitely wanted to get more involved in things like trail upkeep and advocacy and I’ve felt a little hesitant because of my own anxiety about being a noticeably black queer person in the wilderness. I’m all fired up to make more space for us out there and help people feel more comfortable being in the outdoors.

Yes! I love this so much for you!! Getting people fired up about making space for queer people in the outdoors was my hope & dream for this article. Thank you so much for reading <3

This is my world! As a queer public servant, I’ve done several of these community-building things (and others). I considered going to this summit but already had plans so it’s lovely to read about it.

P.s. it’s National Park Service (no S on Park) 😉

Thanks for sharing this. I grew up on lots of camping, canoeing, tubing and hiking trips. I absolutely love nature in the outdoors, but often feel nervous in small towns and outdoor spaces. This was truly a breath of fresh air!

Why are events like this so white? I knew before even getting there what the group shot would look like… and putting pictures of the few poc up top was just… so white.

This is awesome Nicole! I’m just now seeing this. Thank you again for interviewing me and for writing this piece. It was so wonderful to meet you :)