This article includes spoilers for the lesbian storyline in 2023’s The Color Purple. If you have not yet seen the film, you might enjoy a spoiler-free review instead.

Premiering this week, more than 40 years after Alice Walker’s Pulitzer Prize book in 1982 and just shy of 20 years after its original 20025 Broadway debut, audiences have been promised a version of The Color Purple that will be a “bold new take on the beloved classic.”

But, what does “bold” mean? In all versions of The Color Purple, the beats of which are familiar to most audiences, Celie, the protagonist, is severely abused by both her stepfather and then later, her husband, Mister. Throughout her life, Celie’s memories of her sister Nettie, along with friendships made with other women along the way, teach her how to be strong in ways she never knew possible. Key to those relationships is Celie’s romantic awakening with her husband’s mistress, Shug Avery. In Alice Walker’s novel, Shug and Celie become lovers to one another and, even after decades, we have yet to see their relationship met with the same ferocity of which Walker first penned them.

In 1982 Alice Walker wrote a Black queer text so ahead of its time, that 40 years later we’re still fighting to catch up. Here is a history of the most famous Black lesbian kiss in our lifetime.

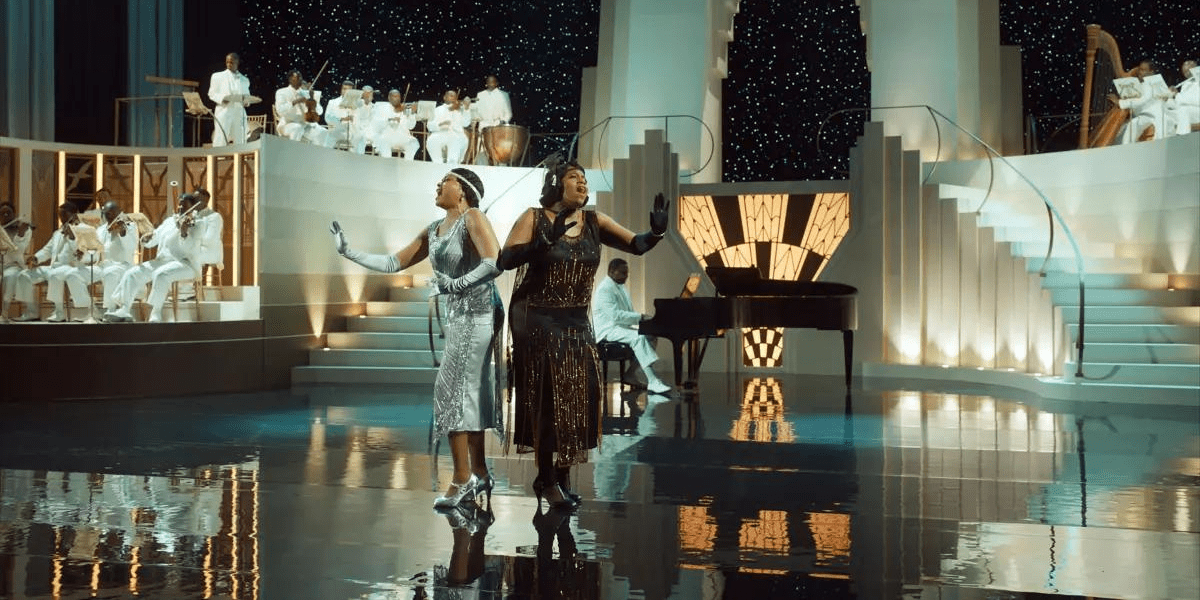

Fantasia Barrino as Celie and Taraji P. Henson as Shug in The Color Purple (2023).

1979: Before The Color Purple

I’d argue that the history of queerness in The Color Purple begins roughly three years before the book even published. In 1979, Black feminist lesbian scholar and activist Barbara Smith wrote “Toward a Black Feminist Criticism,” a pivotal work in feminist theory that continues to be studied for decades. It’s widely accepted as the “the first explicit statement of Black feminist criticism.” At the time, Smith was already considered a leading voice in Black feminist pedagogy, having been a member of the National Black Feminist Organization, the Combahee River Collective, and would go on to found the famed Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press (at her friend Audre Lorde’s suggestion, no less).

Most directly related to our interests, in “Toward a Black a Black Feminist Criticism” Smith argues that all the “segments of the literary world-whether establishment, progressive, Black, female, or lesbian — do not know, or at least act as if they do not know, that Black women writers and Black lesbian writers exist.” This is a rallying call. Black queer and lesbian writers were already building generation-defining careers at the time, but as Dr. Christopher S. Lewis writes in “Cultivating Black Lesbian Shamelessness: Alice Walker’s ‘The Color Purple'” there is one particular trend to note — three years later, in 1982, four seminal Black lesbian texts were all published at the same time: Audre Lorde’s Zami: A New Spelling of My Name, Ntozake Shange’s Sassafrass, Cyprus, & Indigo, Gloria Naylor’s The Women of Brewster Place, and Alice Walker’s The Color Purple.

Of those books — each important in their own way — The Color Purple would go on to win the Pulitzer Prize, becoming the first and still only novel to do so with a Black queer protagonist (Walker never names Celie’s identity directly, though the character is often read as a lesbian). Alice Walker would also become the first queer Black woman writer to win the award.

Taken in that context, it’s not difficult to draw a line directly between Smith’s original lament and what follows. Alice Walker’s The Color Purple is written amidst a wave of other Black queer women writers who are staking a claim. These are women who socialized together, who were each other’s writing partners, creating deeply personal and intellectual overlapping circles. So much of The Color Purple is tied to Alice Walker’s family history, some of which we will talk about in a bit — but it’s also impossible to divorce it from the feminist, queer, political landscape of where it lands.

1982: The Color Purple Is Published

When Alice Walker published The Color Purple, first and foremost she was interested in writing a tribute to grandmother. Her grandmother, Rachel, as described by Walker, was “a kind and loving woman brutally abused by my grandfather.” This description came in in 2019, after an actor in a regional production of The Color Purple refused to play the role of Celie. Based on Walker’s written response, I presume that the actor objected in part to Celie’s queerness:

“It is safe to say, after a frightful life serving and obeying abusive men, who raped in place of ‘making love,’ my grandmother, like Celie, was not attracted to men. She was, in fact, very drawn to my grandfather’s lover, a beautiful woman who was kind to her, the only grown person who ever seemed to notice how remarkable and creative she was. In giving Celie the love of this woman, in every way love can be expressed, I was clear in my intention to demonstrate that she too, like all of us, deserved to be seen, appreciated, and deeply loved by someone who saw her as whole and worthy.”

In writing Celie’s relationship with Shug, Walker felt as if she was paying her grandmother back a gift, providing something in a fictional realm that perhaps her grandmother was or was not able to fulfill in her life. A Black queer granddaughter, finding a connection through her words to the her (likely queer) Black grandmother, who had always been kind to her.

The Color Purple is known for its spirituality, framed by Celie’s letters to God, a fact that has been underscored by the heavy presence of gospel in its musical adaptations. Those Black Christian traditions are often used to distance The Color Purple from its queerness when for Walker they were always knotted together as one and the same, “I believe, and know, that sexual love can be extraordinarily holy, whoever might be engaging in it, I felt I had been able to return a blessing of love to a grandmother who had always offered only blessing and love, when I was a child, to me.” To express love is, intrinsically, an expression of holiness.

When we talk about The Color Purple novel in comparison to the adaptations that follow it, often — especially as gay people — we zero in on how gay the book is. And when we say “how gay the book is” we’re talking about the sex (I’ve also been guilty of this). The fabric of what Walker was painting was so much more.

It’s purposefully Shug who tells Celie “I think it pisses God off if you walk by the color purple in a field somewhere and don’t notice it,” marrying the book’s two central themes, its spirituality and its queerness, into a single sentence. The literal color purple, of course, has historically been used as a code for queerness, a fact that I am sure was not lost on Walker when she wrote both that sentence and the book’s title. At one point in the novel, Celie says that to her all men look like frogs. Walker’s decision to write Shug as a blues singer pulls from a well-known history queer blues singers during the early 20th century; though I’d argue most prominently Bessie Smith, whose biography had just published in the decade prior, explicitly naming her bisexuality, and like Shug often get lovers of both genders at the same time. Celie’s chosen career path towards financial independence is to make pants — which is certainly a small note within the broader themes of the book, but has been read as a symbol of her queerness by quite a few gay readers. There are so many ways that queerness in The Color Purple is about wholeness far beyond sex.

But also, there is the sex. Celie washing Shug’s body becomes a moment of awakening, Shug is the first person to teach Celie about her clitoris, that sex can feel good, and the first person to guide her through masturbation and oral sex. Theirs is the only time that Celie experiences caring, loving, consensual sex. In fact, at the time of its publishing, The Color Purple contained one of the most vibrant and explicitly described sex scenes — between partners of any gender — up to that point in history. Celie becomes insatiable, writing in her letters “I am like a bee. Shug likes honey. I am after her all the time.” Their relationship spans decades.

Still, it is about what their sex teaches Celie. Walker uses Shug to help Celie regain her voice, her courage, her self-worth, her independence. In her 1997 book The Same River Twice: Honoring the Difficult, Walker reflected that she wrote The Color Purple because she “wanted to give my family and friends an opportunity to see women-loving women — lesbian, heterosexual, bi-sexual, ‘two-spirited’ — womanist women in a recognizable context. I wanted them, I suppose, to see me.”

1985: The Color Purple (dir. Steven Spielberg) Is Released

Whoopi Goldberg as Celie and Margaret Avery as Shug in The Color Purple (1985).

In Steven Spielberg’s 1985 adaptation of The Color Purple, Shug’s and Celie’s nuanced, layered queer love story is reduced to a single ambiguous scene, changing the course of all the adaptations that come after.

In it, Celie cries that no one loves her. Shug – who’s first words to Celie upon meeting her are famously “you sho is ugly!” — assures Celie that she loves her, before gently kissing her. First on her right cheek, then her forehead, her left cheek, and finally, her mouth. The camera follows Shug’s hand as it caresses Celie’s shoulder. Then, Celie’s hand as it reaches out to clasp Shug’s. Their faces are reflected back across the room’s mirrors. The camera pans to the bed they are sitting on, before cutting away to a wind chime carrying a tune.

The work with color here is also of note. As opposed of signature purple (the color that Shug tells Celie is from God), as María Frías points out in Walker-Spielberg Tandem and Lesbianism in The Color Purple, “Walker’s verbal and sexual passion is replaced by the predominance of the color red — both Celie and Shug wear sophisticated red clothes — and the lighting, together with a sensual music, give an atmosphere of intimacy, warmth, and complicity.”

Still, whatever subtext might be gleamed from the scene, it’s also a part of clear decision to eliminate the novel’s prominent lesbian themes. Spielberg admits as much in a 2011 retrospective of his work with Entertainment Weekly, saying “There were certain things in the [lesbian] relationship between Shug Avery and Celie that were finely detailed in Alice’s book, that I didn’t feel could get a [PG-13] rating.”

In The Same River Twice, Walker similarly recalls hearing from The Color Purple producer Quincy Jones that there had been numerous letters from people who were “adamantly opposed to any display of sexual affection between Celie and Shug,” including threats of boycotting the film if those scenes were included.

This also aligns with Whoopi Goldberg’s memory. In a career retrospective with The Television Academy, Goldberg names the NAACP’s attempted boycott campaign as being one of the reasons that The Color Purple, nominated for 11 Oscars, walked away with none. The NAACP’s protests, and surrounding conversations, focused largely on the character of Mister and what that role said about Black masculinity. Still, the hot point of the film’s potential queerness was not lost on conservative audiences. As Goldberg jokes, in the mid-1980s saying the word “lesbian” on screen was barely permissible, let alone being able to depict a multi-faceted queer sexuality.

The small scene in 1985’s The Color Purple we were provided with came at Alice Walker’s instance. Even still, as Walker looked back, “I knew the passion of Celie and Shug’s relationship would be sacrificed when, on the day ‘the kiss’ was shot, Quincy reassured me that Steven had shot it ‘five or six’ different ways, all of them ‘tasteful.'” (Italicizing my own.)

That decision has ultimately haunted Spielberg’s career. He’s acknowledged, “I was shy about it. In that sense, perhaps I was the wrong director to acquit some of the more sexually honest encounters between Shug and Celie.” But when pressed if, given the benefit of time, would he change that decision, Spielberg holds firm: “I wouldn’t, no. That kiss is consistent with the tonality, from beginning to end, of The Color Purple that I adapted.”

While that might be true, it’s not consistent with the novel that Alice Walker wrote.

2005 and 2015: The Color Purple (And Its Revival) Premiere on Broadway

Jennifer Hudson as Shug and Cynthia Erivo as Celie in The Color Purple (2015).

Walker’s unease with Spielberg’s adaptation led Scott Sanders, producer of The Color Purple musical, to approach her with care and caution about his interest in adapting her work for the stage. In an interview with The Los Angeles Times (a piece which, in full disclosure, also cited my recent review of The Color Purple — a fact I discovered while conducting research for this article), Sanders reflected that Walker told him, “‘The relationship between Celie and Shug is very important to me.'” In return, Sanders promised that he wanted to expand their relationship beyond what was depicted in the film, saying “‘This is Broadway, we can touch on subjects like this, it’s not an issue.'”

And, despite the fact that various interpretations of the musical and its revival over the years (based on individual stagings, director’s choices, or companies) still often attempt downplay Shug and Celie’s relationship, Brenda Russell, Allee Willis and Stephen Bray’s lyrics hold true to Sanders’ word. They crystalize two women in love, and the subsequent impact that love story has on every other part of Celie’s life.

In “Dear God — Shug,” Celie washes Shug while Shug recuperates from her overuse of alcohol. Celie compares witnessing Shug’s naked form to worship (“I wash her body and it feel like I’m prayin’/ Try not to look, but my eyes ain’t obeyin'”). Later, when Shug overhears the verbal abuse that Mister spews at Celie, she has a love confession of her own in “Too Beautiful for Words.” When the pair first met, Shug said “you sho is ugly,” but now? Shug tells Celie, “The grace you bring into this world’s / Too beautiful for words… Oh, don’t you know you’re beautiful / Too beautiful for words.”

It’s the first time anyone in Celie’s life (besides her sister, Nettie) has seen beauty in her.

After Shug performs at Harpo’s Juke Joint (a song called “Push Da Button,” most certainly a reference to the fact that in the 1982 novel, Shug teaches Celie about the pleasure brought forth by her own anatomy through referring to her clitoris as a button), Shug and Celie steal away to spend the evening together. In the privacy of Celie’s bedroom they kiss, and in “What About Love” they proclaim not only their love for each other, but their vulnerability.

Celie can’t believe it, “Is that me who’s floating away / Lifted up to the clouds by a kiss / Never felt nothing like this.” While Shug, despite being far more experienced, finds herself stunned at the dawning of this new relationship. “Is that me I don’t recognize / …I had it all figured out.”

They ask each other:

“But what about trust? /

What about tenderness?

What about tears when I’m happy?

What about wings when I fall?

I want you to be a story for me that I can believe in

Forever”

It is, to the best of my knowledge and research, the only love song between two Black women to have ever been performed on Broadway.

When Shug asks Celie what she wants, Celie admits that more than anything, she just wants to be with Shug. This sets the plan in motion for Celie to leave her abusive home to live with Shug in Memphis. Once settled at Shug’s home the couple, along with Shug’s husband, Grady, and Harpo’s ex-girlfriend, Squeak, form a kind of queer domesticity. Grady and Squeak eventually decide to become a couple on their own; Shug and Celie stay together.

Ultimately, Celie and Shug break up. Shug wants Celie’s permission to run away into a short affair with a 19-year-old blues flutist in her band. Celie refuses, singing back their original promise to each other through her tears (this is called the “What About Love (Reprise)”). In their own way, in their own time period, Celie and Shug took vows. While its painful, Celie lets Shug go because in their relationship she saw and found value in her own self-worth.

From their breakup comes Celie’s “I’m Here,” a barn burner of a ballad that has brought every house I’ve ever seen it performed in to tears. It’s there that Celie finally repeats back the words that Shug first sang to her, “I’m beautiful.. yes, I’m beautiful.” This time, she believes it.

As the show comes to a close, Celie sings another refrain in her reprise of the titular “The Color Purple”:

“God is inside me and everyone else

That was or ever will be

I came into this world with God

And when I finally looked inside

I found it.”

Those are words that, once again, Celie first heard on Shug’s lips. It’s the last memory given to the audience. That through Shug, Celie learns to love herself, to find her beauty, and to find her God.

2023: The Color Purple (dir. Blitz Bazawule) Is Released

Taraji P. Henson as Shug and Fantasia Barrino as Celie in The Color Purple (2023).

For his take on the work, now four decades in the making, director Blitz Bazawule was tasked with joining together both Spielberg’s adaptation of The Color Purple that is familiar to most audiences, along with its musical partner, and Walker’s own source material.

Specifically, producer Scott Sanders has said “it was important for us to make it abundantly clear to audiences that these two women had both a sexual relationship and a loving relationship, and that Celie had one love in this entire story.” That sentiment is echoed by screenwriter Marcus Gardley, who noted ahead of the film’s premiere that “I wanted the love story to be prominent and didn’t want to brush over that these two women are in love.”

In Bazawule’s version, Shug no longer calls Celie “ugly” when first meeting her, but in exchange she also never gets to sing her first love song to Celie, she never gets to tell her that she is “too beautiful for words.” That decision undercuts the foundation of their relationship; it’s in the reflection of Shug’s warmth that Celie is supposed to find herself for the first time.

Instead, the majority of Shug and Celie’s relationship occurs in Celie’s imagination, as opposed to within the main text of the film. Throughout The Color Purple, Bazawule inserts stylized asides to bring forth some of the musical elements, particularly (though not only) as it relates to Celie’s inner thoughts. These choices directly impact Shug and Celie. Instead of Celie and Shug’s romance existing as a part of our lived reality, they now find each other inside of a small world of Celie’s own creation.

There are moments where this magical realism approach strengthens the narrative, such as when Celie washes Shug’s body for the first time and the world melts away around them. There are others, such as musical’s signature love song “What About Love,” where Bazawule’s direction feels less clear.

In this version of “What About Love,” Shug sweeps Celie away on a private date to an empty theater, and Celie imagines the two of them together in the style of an old Broadway musical, proclaiming their love. However, since the song now takes place in Celie’s imagination, the audience is left wondering if their love declarations and vows are even real or long-lasting. Worse, while singing a song about lovers who are learning what it means to trust in each other, both Fantasia Barrino and Taraji P. Henson are puzzlingly directed to walk away from each other, rather than become close.

The two do still kiss, a chaste and closed mouth one (though, admittedly, long). The camera slowly pulls away from the couple, instead of inviting the audience into their intimacy. Bazawule confusingly also chooses to backlight their silhouettes in this moment, one that queer audiences in particular have waited nearly 40 years for, leaving Shug and Celie in shadows — as if to say that theirs is a love that is meant to hide.

“Celie’s mind goes into this incredible place of what she believes love is, and when she comes back into reality, it has happened to her,” Bazawule explained to the Los Angeles Times.

But we’re never given a full sense of what this moment means to Shug. The next morning, presumably following their first time together (the actual sex scene in question is cut away), we see Shug’s hand graze Celie’s waist. Mere seconds later, Shug is already out of bed and never looks back at the woman she spent the night with? Their long-term relationship is not established and their time together is never directly mentioned again, almost as if to apologize to film audiences for its inclusion at all. It’s not made clear that Celie later moves to Memphis to be in a relationship with Shug. Their break up song (a return to “What About Love”) is cut entirely, thus robbing Celie’s most famous ballad, “I’m Here,” of its key queer catalyst.

The team behind the new Color Purple has argued that the decision to divorce “I’m Here” from Shug and Celie’s breakup is to recenter it on Celie’s own self-definition and self-creation, rather than have it be in response to a broken heart. They see this is Celie coming into her own, on her own terms.

But of course, Celie coming into her own in the context of her relationship with Shug is… what the story is supposed to be about. It is from Shug that Celie that learns she is beautiful. It is from Shug’s heartbreak that Celie learns that “I don’t need you to love me” because she can love herself. In the setup of the newest The Color Purple, she learns neither.

In his interview with the The Los Angeles Times, Scott Sanders responded to similar criticisms of the new adaptation, stating “There was nothing intentional to soften the relationship and, quite frankly, we thought we did a beautiful job with it… We show that they kissed, that they were romantic, that they slept together at least once. But how many scenes do you want to keep going back to the bedroom?”

While it’s true that an awkwardly backlit kiss, two fantasy sequences, and a suggested night together moves the needle on this latest The Color Purple film closer than the last time the story was depicted on screen, it’s simultaneously still a far cry from what Walker actually wrote and the reasons why she wrote it.

Brooke Obie put it well for Andscape, Blitz Bazawule “makes a choice to show us the bed shaking as Celie is raped by Mister. And he also makes a choice not to show us Celie’s consensual, sexual romance with Shug that’s foundational to who she becomes. It matters that Celie’s relationship with God and herself are discovered and explored through the lens of her lesbianism. It’s a necessary testament to the liberating force and inherent holiness of queerness.”

(Sanders wondered, “how many scenes do you want to keep going back to the bedroom?” I’d argue, at least as many times as Celie is shown being raped. But that’s just me, personally.)

Notably, the new Color Purple also neglects to make it clear that it is Shug, along with Mister, who helps bring Nettie home to Celie after all their years apart. Thus depriving Shug of the final moment where she shows her love for Celie by reuniting her with the greatest love in her life, her sister. This changes the tone of Celie singing the film’s concluding “Color Purple (Reprise)” lyrics altogether, removing direct context of Shug from Celie’s final words.

Funny how that worked out.

I don’t know where The Color Purple will go from here. I hope that one day, maybe in time for its next revival in 2040, we’ll finally be able to match the complexity and beauty of a love story between two Black Southern queer woman that Alice Walker wrote back in 1982. It will have been a long, hard fought, winding road — a history of half-truths and choked silences, of two steps forward and one step back, but one with a destination of hope. And I believe that seeing our wholeness and holiness will have been worth it.

thank you for this thoughtful examination Carmen! i truly think that the only way we’ll get to see Celie and Shug’s relationship play out the way it is supposed to be is if a Black queer woman adapts it.

💯

I’d love to see that

Interesting article. As someone who hasn’t read the book or seen the Spielberg movie and wasn’t that familiar with the story, I thought the new movie made their relationship very clear, that Celie obviously had a lesbian awakening, and that they were together after leaving and remained together for the rest of the movie. Sounds like it’s (long past) time to read the book!

Thank you for this, Carmen. It is absolutely maddening that Celie and Shug’s relationship continues to be downplayed on screen, even in 2023. Thank the Lesbian Jesus for the Broadway adaptation!

Thank you so much for this article highly informative and enjoyable!!!!!!!!

I’ve read quite a few articles from you Carmen but this… this was so good, I think I have to come back again. A part of me was tempted to flag the parts I enjoyed the most but the truth is that there isn’t a single word that did not sing here. Thank you for writing this.

I could not agree more!

I’ve been dreaming about a Dee Rees adapted/directed Colour Purple since Pariah and Bessie, she’s the only artist I can think of who could nail the interiority, eroticism and musicality of the book and musical.

It’s a shame this version doesn’t seem especially interested in the complexity of Shug and Celine’s relationship arc, the defensiveness of ‘see we let them kiss and spend the night together’ just shows such a missed perspective of all the wonderfully detailed beats that exist within the text.

This is beautifully written and important. Thank you!

THANK YOU SO MUCH FOR THIS REVIEW!! I’m so grateful Autostraddle is a place where this history and perspective can be articulated.

I would also add that the scene where Celie washes Shug is played for laughs ultimately, because it ends with Celie doing something clumsy because she’s daydreaming and Shug being like WTF? Further reducing Celies queerness to a punchline, encouraging audiences to laugh, and further confusing the audience as to whether Shug reciprocates Celies attraction at all.

In elementary school I read the book, and in middle school I saw the movie and read the book again. I have come back to it twice in my adult life, suffice to say it has made an impact on me.

When watching the movie I remember feeling acute aching lesbian anticipation for the Shug and Celie scenes. While watching, that horrible feeling happened where you had to accept that realness would be excluded from the story and at the same time also feeling so desperate for validation. It is such a detrimental experience, definitely a building block of internalized homophobia. Wish there was a word for this.

I did not see the musical and although I want to see the new movie I’m not sure that I will. Thank you for this thoughtful review.

It would be nice if at least one of the websites discussing this book right now would acknowledge that Alice Walker is both a David Icke supporter and an unapologetic hard core TERF, and it kinda sucks her work is still treated with reverence without regard to any of that.

Whoa. I didn’t know any of that.

It’s been driving me nuts as the musical has led to renewed focus on the work.

Here I’ll quote her from her defense of Rowling:

“The use of “guy” for both male and female eroded the ability of children to easily feel confident in which gender they were,” Walker writes in her essay, defending Rowling’s views. “From that confusion, considered irrelevant, apparently, to the forming of young minds, has come much cutting off of parts and restructuring of essential physical equipment. If such restructuring is freely chosen at eighteen or twenty, at least there is a sense the person involved may have lived long enough to know, definitely, what is desired. Younger than that, I feel there may in fact be reason, later on, to mourn and weep. After all, the human body is a miracle, of whatever sex, tampering with a miracle is unlikely to serve us”

She is straight up terrible.

And I kinda hoped this website would be aware of that.

I had set this aside to read and am only now coming back to it. It answers so many of the questions I had after seeing the latest film—the choices particularly in the theater scene confused me. I am sure it took a great deal of time and research so I wanted to circle back and thank you for writing it, Carmen.

Thank you! That is so kind!!

I loved this post! I had never really thought about the significance of the color purple in 90s culture, but now it makes so much sense. Katy’s poem really added depth to the article – thanks for sharing!

This was such a fascinating read! I love how you delved into the cultural significance of the color purple and its evolution over time. It really added depth to my understanding of its impact and representation in different contexts. Thank you for sharing this insightful perspective!