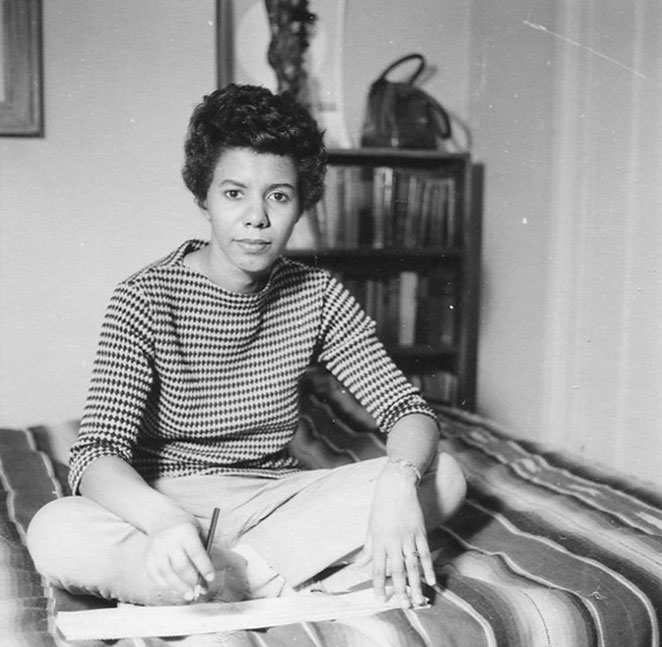

Feature image courtesy of Lorraine Hansberry Properties Trust.

“For some time now—I think since I was a child—I have been possessed of the desire to put down the stuff of my life,” Lorraine Hansberry wrote in To Be Young, Gifted, and Black. That impulse, heightened by the Hansberry family’s harrowing experiences with segregation and discrimination in their native Chicago, drove her to write one of the greatest American theater scripts, A Raisin in the Sun. In a new documentary, airing January 19th on PBS, director Tracy Heather Strain (Race: The Power of an Illusion) picks up what Hansberry put down.

As you might remember from high school English class, Raisin focuses on the Youngers, a family that both resembles Lorraine’s activist/real estate broker kin and their lower-income tenants. When the play’s patriarch passes away, his brood clashes over what to do with his modest life insurance check. Despite having different ideas about how to go about it, each member basically desires the same thing: an easier shot at life in America. Nearly 60 years later, this longing still persists. The first work by a Black woman to be performed on Broadway, Raisin became a commercial and critical success, scooping up the New York Drama Critics Circle Award for Best Play in 1959. It would be adapted for film, using the playwright’s script, in 1961. Lorraine, who wrote as though she’d lived multiple lifetimes, was only 28.

Lorraine’s work was so intensely influenced by her life, so it’s a bit strange to admit that we know more about her plays than we do her biography. But make no mistake: Lorraine—“Sweet Lorraine,” as her friend James Baldwin called her in his eulogy—was a literary rockstar; an uncredited beat poet. She chain-smoked too much. She made it rain on grassroots integrationists in the South while giving the Kennedy brothers a tongue-lashing for their failure to protect the region’s African-Americans. She inspired a Nina Simone song. She was clocked by the Feds. She wore pearl earrings. She gave a generation of Black actors the roles that would define their careers. She bedded white people years before miscegenation was legalized. She pissed off American theater. She pissed off American theater critics. She named her home in upstate New York Chitterling Heights. Years before Stonewall, she penned letters of solidarity to the early lesbian publication The Ladder. She had a mean sense of humor that continues to defy the “serious activist” stereotype. She didn’t stop until her body made her stop.

Sighted Eyes/Feeling Heart: Lorraine Hansberry touches on all of this and more. It’s a first-of-its-kind documentary, connecting the important plays our teachers had us read with the intrepid woman behind them. While there are touches of Lorraine in Raoul Peck’s near-perfect film about Baldwin, I Am Not Your Negro, his documentary concerns itself with the perilous state of race in America first and—by honing in on the author’s murdered friends Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, Jr.—brotherhood second.

But Lorraine, who died at 34 from pancreatic cancer that her doctors and loved ones didn’t notify her she had, was also killed by white America. At the time, the medical establishment regularly encouraged husbands, fathers, and male friends to hide potentially lethal diagnoses from female patients. Ironically, Lurleen Wallace, wife of the governor from Alabama who infamously refused desegregation, faced a similar fate.

When viewing Sighted Eyes/Feeling Heart at DocNYC this past fall, I was struck by Peck’s failure to consider Hansberry’s life and death worth their time on the screen; instead, she was relegated to the footnotes. After seeing I Am Not Your Negro, some moviegoers questioned why Peck didn’t allude to Baldwin’s queerness. It was an inquiry I didn’t feel was mine to answer. But in thinking about Hansberry now, I find myself asking different versions of the same question. Did Peck view sexuality and gender as distractions from his primary subjects (race and masculine solidarity)? Did he not want to ruffle viewers with homophobic or misogynist leanings? Wouldn’t addressing the systematic paternalism that harmed an exceptional Black woman only enhance the ongoing conversations about race in America? While it won’t kill us to acknowledge multiplicity, it certainly will if we don’t.

Sighted Eyes/Feeling Heart, fourteen years in the making, is a great example of a work that thoughtfully and creatively layers ideas about gender and sexuality alongside race. In addition to readings from Lorraine’s private journals, the film features a ton of esteemed folks familiar with her, from feminist scholars and theater critics to legendary actors like Sidney Poitier and subversive writers like Ann Bannon; some of whom weren’t afraid to spar with one another’s ideas or Hansberry’s work on-camera. Like Lorraine’s second play, The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window, Sighted Eyes/Feeling Heart fearlessly and gracefully tackles the mix of identities—femininity and queerness among them—that Peck found too overwhelming.

Like women the world over, Hansberry was deeply influenced by French feminist Simone de Beauvoir’s book The Second Sex; Sighted dramatizes her devouring the book, page by page. As a nod to this, Strain cleverly juxtaposes French pop music and archival footage of happy Black couples, crafting a culture clash that hints that all was not well in domestic paradise. The moment echoes Peck’s pairing of happy white family portraits with voiceovers that critique white ignorance. By indulging each and every social complication, Strain doesn’t seem at all worried that a gentle feminist indictment of the midcentury Black family will derail her life’s work.

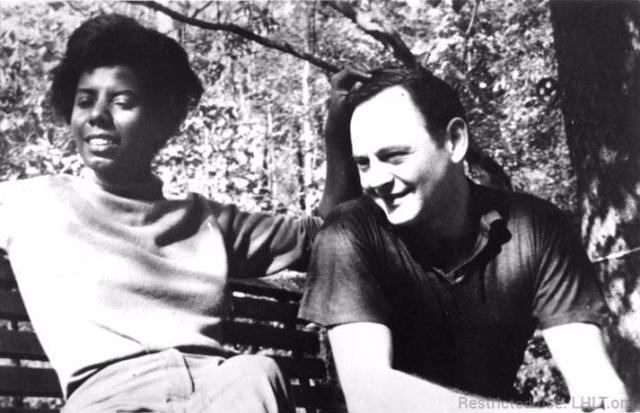

Lorraine moved to NYC in 1950 and married the Jewish publisher Robert Nemiroff three years later; she was 23. It was a creatively beneficial relationship for both, Robert penning songs and Lorraine toiling over—and sometimes nearly abandoning— what would become her first play, A Raisin in the Sun. Upon coming into some serious cash, Robert was able to bankroll Hansberry’s career, and, posthumously, serve as her literary executor.

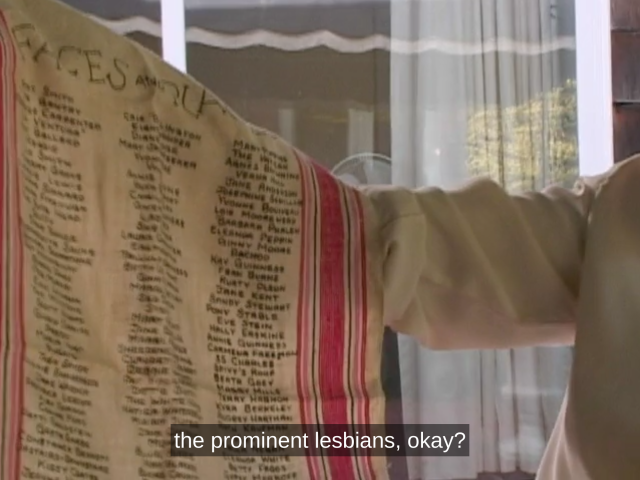

While Lorraine’s political alignment with early gay activists is old news, Sighted Eyes/Feeling Heart is the first major effort to confirm and embrace Hansberry’s own orientation. By the time the couple divorced 1962, Lorraine had long been actively and delightfully gay, having published pulp under the pen name Emily Smith and—as the late, great, Edie Windsor divulges in interview—partied on Manhattan’s mafia-owned lesbian bar circuit. This second revelation sent me scampering back to Edie & Thea: A Very Long Engagement to see if Lorraine’s name or pseudonym was on that “prominent lesbians circa 1960″ towel that Edie eagerly whips out. As far as I can tell, she wasn’t. Apart from her own journals that use acronyms for her queer loves, Hansberry didn’t leave much trace of her romantic past. As the director explained in a Q&A after the film, she was able to locate at least one woman who’d had a relationship with Lorraine, but—wary of either disrupting the writer’s legacy or unethically outing the dead—she backed out of being interviewed at the last moment.

It’s in Sighted’s moments of thoughtful picking and choosing what to include that Strain is her best. She finds a great balance between the humanity and humor that should define how we remember Lorraine. In one of the playwright’s trademark end-of-year lists, dramatized in the film, Lorraine annotates her ‘likes.’ As obsessed with the why and the who of human life as ever, the list includes ‘my homosexuality’ and ‘Eartha Kitt.’ Same girl, same.

If I were to make a belated Hansberry-style end-of-year list for 2017, this doc would definitely be on it.

Lorraine Hansberry: Sighted Eyes/Feeling Heart airs Friday, January 19 at 9 p.m. on PBS, and will be streaming online Saturday on PBS.org.

Comments

I AM GAY FOR THIS!!

(also thank you for this thorough write up, I can’t wait to see it)

Yr very welcome! I hope you come back and tell us all of your thoughts!

I gasped aloud when I saw this. Lorraine Hansberry is everything.

Just finished watching it. This documentary is everything.

So excited for this! I saw her letters to The Ladder at the Brooklyn Museum show you mentioned and fell in love with her fierce wit.

Hi! I wanted to add something that didn’t feel 100% relevant to the film (which Robert had a role in creating).

Shortly after I finished writing this, the @lgbt_history Insta I <3 so much commemorated Lorraine's death with a post that, like the doc, goes into more depth about her childhood and also casts Robert's handling of Lorraine's estate in a much more critical light. It's worth including this in the conversation, I think.

https://www.instagram.com/p/Bd2nwpVjq-o/?hl=en&taken-by=lgbt_history