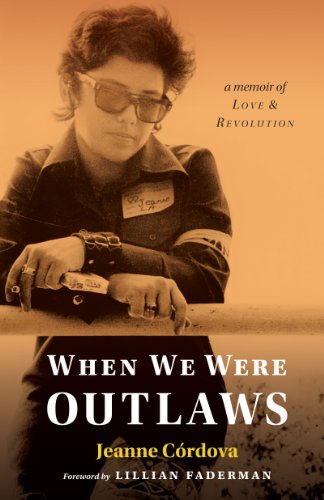

Of the many disparaging terms that have been applied to the 1970s women’s liberation movement, perhaps the most damning, in our contemporary “sex positive” culture, is “unsexy.” “Puritanical,” “moralistic,” “anti-sex”: even lesbians sometimes fling these terms at the second wave. If appellations like “prudish” or “anti-erotic” sound to you like apt descriptors of second wave lesbian feminists, then Jeanne Córdova’s memoir, When We Were Outlaws (Spinsters Ink, 2011), will make you rethink what you think you know about feminist history.

If you’re not familiar with the name Jeanne Córdova, this is a measure of the extent to which contemporary historiographies of queerness have erased, or revised beyond recognition, the world-changing political work of lesbian feminists. Córdova was the founder and News Editor of the Lesbian Tide, a widely read newsmagazine that was the first periodical in the U.S. to boast the word “lesbian” in its title. She was also a key organizer of the National Lesbian Conference at UCLA in 1973, which at the time was the biggest gathering of lesbians in history. And she worked as an investigative reporter for the radical Los Angeles Free Press; her assignments for the Press included interviews with Angela Davis (Córdova accurately intuited that Davis was a lesbian and pressed her, unsuccessfully, to come out), the Weather Underground (whose members led Córdova, blindfolded, to their secret meeting place) and Emily Harris (Harris was a member of the Symbionese Liberation Army, the kidnappers of Patty Hearst; after her capture by the police, she granted Córdova her first interview from jail).

“Being an activist leader brought dozens of women to my bed,” Córdova recalls. “Power seemed to attract people, and my political life put me at the center of the action.” Córdova was far from the only lesbian feminist who was getting lots of action. Monogamy was passé and patriarchal, so lesbians juggled primary and secondary lovers, who were squeezed into schedules crammed full of political and social events — women’s meetings, marches, kiss-ins, concerts, collectives, dances, and protests — which were pulsing with erotic energy. Think the second wave was all vanilla, all the time? The sex scenes in When We Were Outlaws shatter that misconception. Although the lesbian feminists of the 1970s are often caricatured as dour and dull, Córdova’s exciting book shows that these were sexy, powerful, creative, daring, and passionate women.

They were also a far more racially and ethnically diverse group than the familiar cliché of the second wave as a “white woman’s movement” suggests. The stereotype of 1970s lesbian feminism as a white movement obscures the important contributions that women of color — including Córdova, who is Chicana — made to second wave political activism. When We Were Outlaws details the ways that the women’s movement unfolded alongside, and in alliance with, numerous other social justice movements, such as Black equality, Black nationalism, and Chicano liberation. These alliances are illustrated in Córdova’s memoir when, at a strategizing session convened to teach lesbians how to resist the surveillance and interrogation techniques of the FBI (who routinely spied upon political activists), Córdova chats with a lesbian feminist friend who participates in both the women’s movement and “solidarity work with Central American causes.”

Today, lesbian feminists of the 1970s have a reputation for having been transphobic. This charge does not take account of the very different conceptions of gender identity that prevailed in this earlier era. As Córdova explained in an interview with me:

In the 1970s the terms “trans” and “transgender” were unknown — except for a few entertainers like Christine Jorgenson and small groups of mostly African American sex workers, who related to the “drag queen” parts of the gay and lesbian movement and called themselves transsexuals. There were a very few lesbian activists who called themselves transsexuals. The one I was closest to was Sue Cooke, a Lesbian Tide photographer for many years. Anyone who called herself a woman was welcome to serve on our staff. The National Lesbian Conference of 1973 at UCLA was the first time I heard that the issue of transsexuals in the lesbian feminist movement was controversial. A transsexual woman had intended to sing during a talent show, but she was surrounded by a major controversy over whether she, as a trans person, should be allowed on stage at a lesbian conference. A vote was taken on this question, and the vote was something like 740 to 765. I don’t remember who got the majority, but the vote stays in my mind because it was so evenly split.

Clearly, second wave radical lesbian feminist opinion was not monolithic in regard to the issue of trans inclusion. Although this topic does not come up in When We Were Outlaws, Córdova, who herself is a gender nonconforming woman and a longtime trans ally, has published numerous essays in support of trans activism.

Córdova’s memoir also gives lie to the oft-repeated claim that it was rigid identitarianism on the part of second-wave feminists that led many lesbians to shun working with men. Córdova recounts her betrayal by her “political godfather,” Morris Kight, a prominent figure in the Gay Liberation movement who had helped the young Córdova acquire the political organizing savvy that she would put to use throughout her lifelong career as a political activist. Unfortunately, Kight proved to be as sexist as Córdova’s real father, who, when Córdova was nineteen, physically threw her and her lover out of his house and onto his front lawn (nearly breaking Cordova’s lover’s knee in the process) when he realized they were lesbians. As the director of the powerful Gay Community Services Center, Kight illegally fired eleven of the center’s feminist employees, including Córdova; the “Gay/Feminist 11” and their supporters then took the desperate — and for Córdova, very ambivalent — step of going on strike against a gay organization. In the midst of formal negotiations with the strikers (whom he insisted on calling “dissidents”), Kight stated bluntly, “GCSC is about gay liberation. I can see in retrospect that we shouldn’t have hired you feminists in the first place.” Los Angeles lesbian feminist activists’ split from gay men, Córdova explains, was part of a nationwide trend, as lesbians across the country were repeatedly confronted by many gay men’s intractable hostility toward feminism.

In the hands of a less skillful storyteller, the minutiae of decades-old political controversies and intra-movement conflicts could easily become tedious. But Córdova’s “novelized memoir” is riveting. The book segues between an account of the author’s adventures as a dynamic and highly accomplished activist and a portrayal, both comic and poignant, of her not-so-smoothly-conducted romantic affairs. Unsparingly honest in her rendition of what she now describes as her “sexist training,” Córdova depicts her younger self as a twenty-six-year-old “baby butch-looking dykelet” who does not always treat the two femmes in her life with honesty and respect (for example, after professing her love to her secondary lover, she comes home to a dinner prepared by her live-in girlfriend, to whom she insists that the other relationship is only a casual affair). I alternated between laughing and fuming at Córdova’s buffoon-like behavior, which provided a striking contrast to the integrity and commitment that characterize her political work. At times, I wanted to halt the flow of the fast-paced narrative, reach inside the book, and shake the young lesbian Córdova was in 1974 — and after shaking her, make her sit down and listen to a lecture inspired by the principles (such as “The personal is political”) that her generation of feminists taught mine (I was in nursery school and kindergarten during the crucial years of the women’s movement that When We Were Outlaws brings to life).

Eventually, Córdova suggests, she will learn these feminist lessons herself. During one of the pivotal moments in her story, a heartbroken Córdova, embroiled in the controversy with the Gay Community Services Center, seeks advice from the influential Los Angeles Radical Feminist Therapy Collective. Radical feminist therapy, which grew out of the anti-psychiatry movement, asserted that ordinary people could solve their problems without the help of mental health professionals; in “problem-solving” groups, radical therapists taught that being truthful about one’s emotions and identifying political oppression as the source of psychic pain were key to living an honorable life and effecting radical political change. “What do you need, Córdova, to get centered today?” asks one of RFTC’s members, initiating a session in which the radical feminist therapists guide Córdova in getting in touch with her pain, her feelings of powerlessness, and her rage — and, from that place, help her craft a better political strategy. This is one of many scenes in When We Were Outlaws that vividly illustrate the brilliance, the inventiveness, the energy, the courage, the dedication — and yes, the sexiness — of the women’s liberation movement. Córdova’s remarkable history of a life at the center of a world-transformative social movement should be read by all lesbians, feminists, and political activists — and indeed by anyone who wants to know, as Córdova asks, “How does one recognize a social movement when it comes calling at your door?”

Anna Mollow’s essays on queerness, feminism, fat politics, disability, and chronic illness have appeared or are forthcoming in Bitch, WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly, Social Text Online, The Journal of Literary and Cultural Disability Studies, MELUS: Multi-Ethnic Literature of the United States, and the Disability Studies Reader. She is the coeditor, with Robert McRuer, of Sex and Disability (Duke UP, 2012). Anna is a Ph.D. candidate in English at U.C. Berkeley, where she is the recipient of the Andrew Vincent White and Florence Wales White Scholarship.

“Today, lesbian feminists of the 1970s have a reputation for having been transphobic. This charge does not take account of the very different conceptions of gender identity that prevailed in this earlier era.” I really appreciate Jeanne Cordova as being one of the few second wave feminists who wasn’t also transphobic. Truly I do, she deserves big props for it. Along with people like Angela Davis (who has made some very positive statements about trans people and the Rev. Freda Smith (one of the founders of the Metropolitan Community Church) as well as a few feminists like Andrea Dworkin (who was, at least, on the middle of that issue), there were a few people who weren’t transphobes. But most were, and overwhelmingly were virulently so. And, btw, include respected people like Gloria Steinem and Adrienne Rich in that camp.

It had nothing to do with supposed ‘different conceptions of gender identity’ or that no trans women were known. Beth Elliot, the trans woman Cordova is referring to, was viciously and decisively kicked out of a lesbian feminist conference in 1973 after being long involved with that movement… people were screaming at her and calling her a rapist (not for what she did but for who she was). She was very well known at the time. A little later in the 70s Sandy Stone was fired from Olivia records because she was trans (and yes, there were a few women who worked at Olivia who defended her) because of the outcry from 2nd wave transphobes. This was a very well known case in the women’s community. And the reality is, many of these second wave transphobes are still saying the same old-same old old or haven’t even bothered to own up to their attitudes during that era. Nor does being a gender variant woman like Cordova mean you’re likely to not be a transmisogynist. Some of the worst transphobes in that movement were MOC people.

Again, I appreciate the history from an amazing feminist and woman like Cordova but, in the process, please don’t smooth or finesse over the transphobic ugliness which was/is a reality of the vast majority of 2nd wave feminists. It starts sounding like making excuses.

Well put. A wonderful response.

I’d add that, seeing Mollow’s link which supposedly situated Cordova as a trans ally, such an identification deserves an asterisk. Her enthusiastic embrace of the MichFest founder Vogel’s statement this spring, in which trans women were again strictly banned from MichFest, and her lack of support for the boycott, is not allyship in my book, at least. Cordova’s language suggests tepid liberal tolerance rather than understanding acceptance. After 22 years, the time for gradual “change from within” patience is over. Done.

Having personally experienced the irrational transphobic hate from TERf’s in very violent ways, this sort of “finesse” is incredibly offensive. It’s 2013, and we are still the bottom of the barrel to most cis people – feminist, right-winger, whatever… It hurts and gnaws at my heart. It really does.

In all fairness to Cordova, she both accepted certain parts of Lisa Vogel’s statement and challenged other parts of it. She questioned the very concept of a universal “raised as a woman” experience which is one of the core tenants of MichFest’s exclusion policy. Yes, she did consider Vogel’s self-serving recent statement about the WBW policy to be healing and thoughtful, which I seriously question. She agrees with Vogel’s statement that the very act of including trans women as part of the MichFest community is inherently destroying the very identity of WBW… which, IMO, is kind of absurd. But Cordova isn’t anywhere near what I would consider a transphobe second wave style and she genuinely seems to want inclusion of trans women (just maybe while being rather too solicitous of the feelings of genuinely transphobic people). I don’t like to see people with widely disparate views (say, a nasty transphobe like Robin Morgan and someone like Jeanne Cordova) tossed into the same barrel… I don’t think that’s fair either.

A million times this. The wealth of anti-trans theories, attitudes, and manifestos that came out of the second wave (and the near-complete dearth of counter-argument within the movement at the time) play a significant part in why I, as an openly queer and not-100%-cis-passing trans woman, have virtually zero safe spaces in the world where I know my very identity will not be put on trial.

The article’s points about the attitudes in the sex-positive movement toward the ideas and expressions around sex from the second wave are well-taken, and I’m glad I read them and was given something to think about. The whole section of the article sweeping aside the virulent transmisogyny of the movement came off very badly and dismissively to me. If it was meant to have a different effect, that intention was not carried through the writing.

Wow… O.o

The erasure here of the endemic transphobia which infected the feminist world of those days (and still does in certain circles) is totally not ok.

For instance, the “votes” to which “Mustang Sally” was humiliatingly put, as if that were in any way ok, were far from civil. She was widely abused, screamed at, dehumanized, her safety threatened. She was booed off the stage for her very existence. As were ALL transsexual women of the time in supposedly “safe” womynspace.

And it is laughable to imply trans women weren’t there in numbers, pitching in from the beginning. Cordova betrays her incredible ignorance in this. Silvia Rivera, Beth Eliot, Sandy Stone… Such activist names are hardly obscure; the outrageous public abuse they received through the 70’s is on record. By 1980, the chorus of “tranny hunt” hate was so loud, most trans women in feminist and lesbian circles had been driven away or into deep stealth. For about twenty years, the mainstream view in feminist circles was one of emphatic cissexist, transmisogynistic rejection of trans people, especially and ironically against women, which has had long and lasting effects to this day via increasing the marginalization of trans people in society. “The Transsexual Empire” was their bible. Feminists of repute such as Janice Raymond, Mary Daly, Germaine Greer, etc. worked with right wing hate groups to secure a regime of social violence which set all trans people back 25 years.

We simply had no real ally presence back then. Not in feminism, not in Gay and Lesbian community, not in the mainstream. No matter how many cis lesbian feminists had private reservations, they weren’t piping up. The actual record shows that “clearly”, second wave transphobia was practically monolithic.

For whatever obtuse rationales of rigid ideology or base emotion, trans women were the most hated, sacrificial Others of the feminist movement during the Second Wave. That Cordova (and Mollow) would cavalierly dismiss this, minimize the issue even to the point of suggesting that trans women weren’t present in palpable ways in lesbian activism, is disrespectful to the victims of this “herstory” of violence enacted by privileged cis feminists on trans bodies.

For a more comprehensive review of the shameful events alluded to, I suggest this – http://queerswithoutborders.com/QueerArchives/1971/01/the-gay-lesbian-and-feminist-backlash-against-trans-folks/

Attempts to apologize for the bigotry of the past only scares away women who might embrace the whole story of feminism if it was told with more honesty.

It is so telling that she couldn’t remember how the vote went down…no one who has ever had the validity of their existence put to a vote (or who cares about someone has that done to them) would ever forget the outcome. Pleading that people didn’t know better back then is ridiculous (half the people in that evil vote knew better). Claiming her as an ally now is utterly absurd.

Thank you Brighid and Ginapdx for summing this problem up better than I can. I get way too upset talking about the cruelty of my mother’s generation of feminists.

Whichever way what happened happened. There’s no way to right it anymore. We can’t do anything, as cultural genocide is not a matter of forgiveness. No one would ask for it – and more to the point, who would have the authority to give it?

The lots have been cast and all we can do is to act the roles fate has handed us with honour. If your role is that of an enemy, an agent of the oppressive system, all you can do is wear the uniform with pride and make sure it’s neat and clean. And do your best…as indeed the big bogeyman that is the mainstream establishment has proven to be MUCH more humane than its opposition ever was:

70s: Organised effort of extermination vs…systemic injustice i guess

90s: Continued persecution bridging generations vs…grudgingly given human rights

2010s: Passive-aggressive lip service vs …actually nothing and being fairly on board and most importantly, doing stuff

It’s an UK timeline but it is illustrative generally. Bite the hand that feeds you? Or settle a vendetta? Your choice.

Of course this is personal for me. My almostgirlfriend (a complicated semi-relationship, she was a transsexual woman) decided on hard reset and i blamed myself for ages for not tearing this rubbish out of her hands and making a book pyre. Nowadays i would do that in a sec.

Millions and millions nightmares and 10 years later my close friend was evicted from a women’s household by a feminist landlady. her crime: bringing home a transsexual woman. The year…was 2013.

But it’s my feelings that are personal – timelines and facts are common and objective.

All i can say – always remember above and beyond all you’re queer women – your sexuality won’t go away and you should be proud of it. And you are entitled to it. And being gay/bi has absolutely nothing to do with belief in systems of political ideology. You are not looking for company of other queer women to change the world according to some idiot’s book. You are doing it to find each other and not to be alone in this world. You belong here – and it’s ideologies that can fuck off and look for their drones and peons elsewhere.

I really appreciate these responses. I genuinely liked everything about this article that did not have to with trans women, but the erasure of our victimhood and downplaying of past atrocities pretty much trumps everything else. Anna, I have no doubt that you had the best of intentions–but it would be really nice to hear your thoughts on some of these replies!

Please forgive me for a very belated comment, but as a transsexual Lesbian feminist of the Second Wave, I would like to affirm that solidarity from my Lesbian sisters who were nontrans was widespread and powerful. Sadly, transphobia was also widespread, so a balanced view needs to acknowledge both sides of the picture.

During the years 1973-1975, I experienced both wonderful inclusiveness in such places as Gay Community News in Boston, where Lesbian feminism was very strong and there were a number of articles published on the intersection and overlap of the Lesbian and transsexual communities, and the kind of anti-trans prejudice expressed against Beth Elliott at the West Coast Lesbian Conference in 1973 and later against Sandy Stone and the Olivia collective in 1976-1978. Fortunately, I did not face an ordeal like that of Elliott or Stone, but certainly encountered prejudice and exclusion.

However, when such prejudice and exclusion arose, there were sisters ready to challenge anti-trans prejudice, including Butch sisters, many of whom experience the day to day marginalization and risk of being a gender variant woman. This is the same spirit shown by Jeanne Cordova in her 2013 statement on Michfest linked to above, in which she addresses Lisa Vogel with respect but makes clear her support for a policy of inclusion for all female-identified people.

Any attempt to deny or downplay the presence of virulent transphobia in the Second Wave would be misguided and wrong. But likewise, to get a balanced perspective, we must not downplay the role either of transsexual Lesbian feminists in the 1970’s, or of the nontrans Lesbian feminist sisters who supported us and sometimes themselves endured personal attacks for the sake of an inclusive women’s community.