Laurie Penny, a columnist and freelance journalist, recently released her book Cybersexism: Sex, Gender and Power on the Internet. This short 42-page work is part of her upcoming book, Unspeakable Things: Sex, Lies and Revolution, which will be published by Bloomsbury in 2014.

The book covers not only misogynistic online abuse as it is most explicitly known (“make me a sandwich, bitch”) but also the more subtle ways in which sexism codes and polices women’s behaviour online. Penny argues that far too much is done in the name of “protecting” women: restricting access to the internet, scaremongering about “sexualisation” (“the magical process whereby pre-teen girls catch a glimpse of some airbrushed boobs on a pop-up ad and are thereby transformed into wanton cybersluts, never to be reclaimed for Jesus”), and naggy, hostile cautions about what we say or do or wear on the internet.

Although the technology is new, the language of shame and sin around women’s use of the Internet is very, very old. The answer seems to be the same as it always has been whenever there’s a moral panic about women in public space: just stay away. Don’t go into these new, exciting worlds; wait for the men to get there first and make it safe for you, and if that doesn’t happen, stay home and read a book.

Social media, she points out, has long overtaken porn as the number one use of the internet. Relegating cybersexism to the domain of shady lurkers fapping to amateur teen porn is archaic and misguided. Just as misogyny was never only for fundamentalist preachers and back alley rapists, the troll is not just the lone dishevelled man living in his parents’ basement. The troll is someone you went to school with or still go to work with; the troll is the man with a verified Twitter account who loves women and just wants them to know what’s best for them. The troll is not a “troll”: the troll is a real person who exists in both physical and virtual spaces, and whose sexism cannot be assumed to be neatly confined to just one sphere.

It’d be nice to think that the rot of rank sexism was confined to fringe sites. The truly frightening thing, though, is that the people sending these messages are often perfectly ordinary men holding down perfectly ordinary jobs: the person who wrote the drooling little note to me above [a violent rape and murder fantasy] and ran the site it appeared on was an estate agent called Richard White, who lived in Sidcup, outer London, with a wife and kids, and just happened to run a hate website directed at women and minorities. The Internet recreates offline prejudices and changes them, twists them, makes them voyeuristic, and anonymity and physical distance make it easier for some individuals to treat other people as less than human.

This is an account and critique of cybersexism that centres Penny’s own experiences, which is both its greatest strength and weakness.

Penny’s writing is strongest when it is her own narrative that takes the stage. Her account of the numerous and varied ways in which the internet has taken root in her life – from LiveJournal to professional writing, “growing up” with the internet, so to speak, as most of her audience is likely to have done – is compelling and relatable, making it easier to appreciate the grey areas of cybersexism and its insidious influence in how we make decisions both online and in real life. Do you put your real name to your writing? Will what you do today end up on Facebook tomorrow, and show up on your future employers’ (or paramours’) Google searches two years from now? How do you deal with rape threats being hurled at you for daring to do so much as game while female? As a very public figure on the internet, there is little doubt that this is an area that Penny is uniquely qualified to talk about – she knows intimately of the bomb threats and paralysing anxiety that she talks of because they come straight from her own life.

Laurie Penny (via Charlotte’s Word Web)

On the flip side, the areas she chooses to focus on at times reflect too much of her personal investment. This is most evident in the disproportionate number of pages devoted to discussing “geek culture,” which, while interesting, seems to clash with important ideas put forth earlier in the book that the internet is not monolithic and that the people who use it – and abuse or control women on it – come in all shades. She curiously subsumes issues to do with the tech industry, which remains infamously hostile to women both as producers and consumers, under this header when this field has grown far beyond the isolated work of hoodie-clad introverted nerds – no matter how hard Mark Zuckerberg’s public image tries to convince us otherwise. The book concludes with optimism that “the social space of the internet will start to look very different […] once the geek community finally wakes up to the fact that the harassment, bullying and intimidating of women online is a clear threat to the principles of freedom of speech and egalitarianism,” rather puzzlingly contradicting the point that she seemed to be initially making that tackling cybersexism requires broader change targeted at a societal level, not at any particular group of internet users.

Mark Zuckerberg: the public face of today’s tech industry, but it’s far from geeks alone who are driving and building this billion-dollar industry (via News One)

The generalisations she makes in the book about what cybersexism looks like and why it comes about run the risk of homogenising the experience of online misogyny, neglecting that it manifests itself in different forms to different people. Especially given the climate in which this book was written and published – in which feminism is increasingly framed against a broader background of intersectional thought – it comes across as a glaring omission that there is not so much as mentions of, say, transmisogyny or hostility towards women of colour (often from within feminist circles).

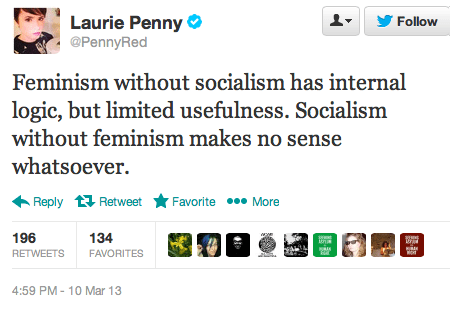

Drawing more on Penny’s background and her work as a socialist feminist, I would’ve been interested to hear her thoughts on how capitalism and sexism intersect on the internet. Working to realise the vision of “the internet is for everyone” requires more than anti-(cyber)sexism, and feminism similarly requires more than online activism, and Penny seems uniquely situated to talk about this; it’s a pity it didn’t come up more.

Cybersexism is neither definitive nor comprehensive, as much as any work can be in this field: it relies on anecdotes and popular examples to back up arguments, and raises more questions than it answers. Aside from a greater understanding of its limitations, a few of which I’ve outlined here, I feel that the book would have benefited from a resource list or in-text links to other works which deal with issues important to cybersexism as an overall phenomenon but tangential to Penny’s specific slant on it.

It’s currently only available as a Kindle Single on Amazon UK (£1.49) and Amazon CA ($2.99). If you don’t have an e-reader, you can download a free reader app or use the Kindle Cloud Reader in your browser.

Laurie Penny is one of my fav young feminist writers, so thank you for linking to this. Maybe she didn’t include transmisogyny in this chapter, but she’s written about it extensively in past and, unlike Caitlin Moran or someone like that, has written about it with power, understanding and compassion.

I completely agree! Which is why it was especially noticeable that she excluded it. I suspect we’re just seeing a work in progress, though, and I’m keen to read the rest of her book when it’s published.

An equally big if not bigger omission seems to me her failure (as far as I can tell) to include information on how the internet is inaccessible to many women with disabilities. Women with disabilities also face the kind of hostility other disadvantaged groups of women face online – but on top of that, they struggle to simply gain access to the internet because of inaccessible technology / websites.

For example, a survey recently published by the Office for National Statistics showed that in the UK 3.8 million disabled adults had never used the internet, and they make up 54% of adults who have never used the internet – http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/rdit2/internet-access-quarterly-update/q2-2013/sty-ia-q2-2013.html

And, I mean, it’s not like there are completely distinct groups of disadvantaged women who struggle to access the internet – women with disabilities who have never accessed the internet tend to be both old and poor, women of colour are more likely to live under the poverty line so they’re less likely to afford an internet connection etc intersectionality etc.

I agree with this too. I am always deeply skeptical of the claim that “the internet is for everyone” whether as an aim or a(n annoyingly idealistic, inaccurate) view of reality. Penny got it right at the start of the book that the internet, for most part, reflects how things already are — both in terms of inequality as it manifests in the online sphere and the inequality in access to this sphere in the first place — and it is nowhere near an egalitarian utopia. This seems to have gotten lost towards the end of it.

I mention the bit in the review about capitalism & sexism exactly because I thought that Penny, as a socialist, would talk more about socioeconomic inequality in access to the internet but it wasn’t there.

It’s one chapter of a book. I’m going to withhold judgement about what it does and doesn’t cover until I can read the entire work (and I’m looking forward to it). I think that’s only fair especially given that she has written about aspects of all these subjects previously.

LAURIE PENNY!! She’s kind of the very good, actually.

I honestly don’t understand why this article doesn’t have more comments because this topic is super relevant and not talked about enough. I’m so glad you brought this book to my attention because I don’t know how many times I’ve had to contend with white male dudebros who insist that sexist trolling is an inevitable part of the Internet that doesn’t reveal anything about a larger trend of societal misogyny. And then, of course, there is the “don’t feed the trolls” mindset, which translates to “put up with anonymous death threats, bullying and a slew of racist/sexist/transphobic comments on a massive scale because responding in any way is giving the ‘trolls’ the reaction they want.”