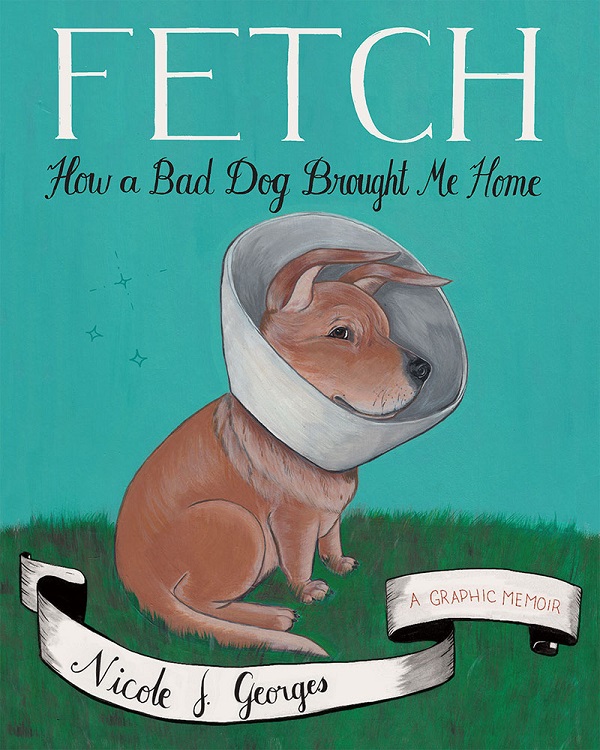

Readers of queer books are quite familiar with coming of age stories, which usually involve the main character moving away from home, exploring different identities, coming out, becoming politicized, and joining like-minded communities. These stories are wonderful, still much-needed — and often indistinguishable from each other. But there’s something quite distinct about the graphic memoir Fetch: How a Bad Dog Brought Me Home by Nicole Georges, a queer feminist coming of age story told through her relationship with her dog.

Georges set out to tell the story of Beija, her “difficult” dog who had recently passed away, but found herself talking about growing up, too. As she explains in an interview with Autostraddle: “I started writing [the memoir] just by thinking about all the different things I needed to say about Beija that were important to her life and, incidentally, they were milestones in my life.” Some were simply important moments Beija was around for; but others, as Georges explains, “were things that, through having to speak up for her, or protect her, or make choices based on her, actually affected my own coming of age and adulthood.”

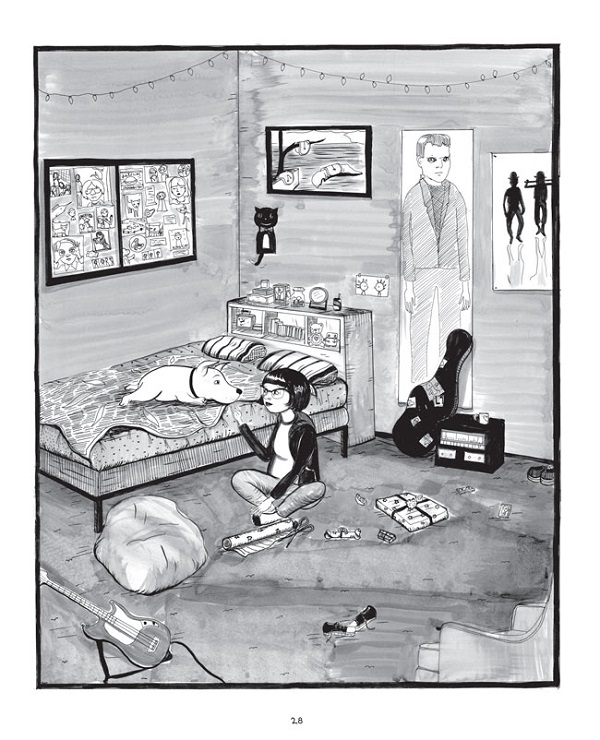

Georges initially bought Beija as a present for her high school boyfriend Tom in an effort to help him heal after having his childhood dog taken away. Even though Georges cleared it with his mom first, his family did not allow him to keep the dog; her family didn’t want another dog, especially not one as high maintenance as Beija. Thus, Beija becomes what Georges calls “the baby I had in high school.” She had no idea how much Beija would change the rest of her life.

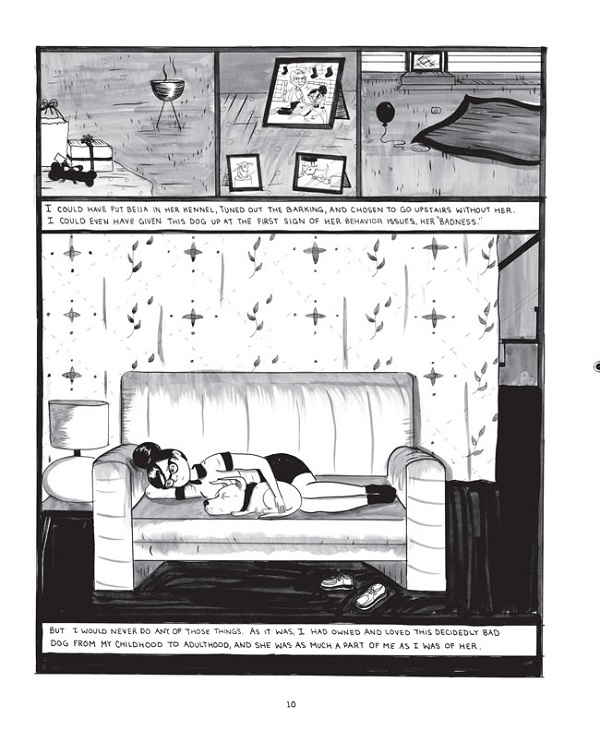

Beija accompanies Georges as she and Tom move to Portland, Oregon; through their eventual break-up; as she moves from one punk house to another; on her journey to the identities queer and feminist; through depression and suicidal thoughts; and along her growing career path as an artist, zinemaker, and graphic memoirist. Beija becomes, in Georges’s words, her “familiar,” her “demon” (like in Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials), or her “horcrux” (a la Harry Potter). As Georges simply puts it: “Dogs are pack animals. Beija and I … were each other’s pack.”

Georges’s fierce determination to protect Beija’s right to body autonomy and consent has clear links to her emerging feminism. Early on in the memoir as yet another person is passing through one of the punk houses Georges lived in, she has to explain to a man why he can’t pet Beija. In response to his comment about why she has such a “funny-looking dog if no one can touch it,” she passionately asserts: “Because she exists for more than that. Beija isn’t here for you to pet. She has her own likes and dislikes, her own desires, and if she says she doesn’t want you to pet her, then back off!”

Such early interactions are the foundation for not only Georges’s budding feminism but also her vegan politics. Georges explains the thinking behind the links between feminism and veganism that the memoir makes, referencing The Sexual Politics of Meat by Carol J. Adams, which:

…puts forth this parallel about how the patriarchy and men talk about women’s bodies and animals’ bodies … They have the same kind of ownership and objectify them in the same way. Sometimes there are those really gross intersections where a pin-up of a woman is sectioned off like cuts of meat. [Adams] draws all those parallels and that imprinted on me. Having my dog not perform in the way that people wanted her to perform, as a dog should, in a subservient way where she was there for their pleasure, I was like, my dog is a fucking awesome dog, and she is deep and she is great, but she’s not for that. And just because she’s not like that doesn’t mean that she doesn’t have worth. Just like if I don’t smile at some guy in the street it doesn’t mean I don’t have value.

As Beija and Georges grow together, there are beautiful moments of humor, vulnerability, and learning. Georges extricates herself from being the “mom” of punk houses and starts spending more time with feminists and lesbians. She comes into her queer identity slowly, sharing a story that disrupts the dominance of the “I-always-knew” gay narrative. There are some beautiful scenes focused on her new interactions with queer women, as Beija sits contentedly in the corner of the panel. Georges elaborates on her exploration of her journey to queerness in the memoir:

I can emotionally connect to cisgender men up to a point. And then after that point I cannot. … Now I know from ‘going gay’ that there’s more, there are deeper levels to go. Everyone I’ve ever dated is on almost exactly the same place on the masculinity scale, actually … But cisgender guys, for whatever reason, be it biology, or the way they were socialized, but I just can’t connect with them as deeply as what makes me 100 percent happy. Now, I think queer is the best word, at least for me it’s the best. It’s fun to call myself homosexual or gay, but queer is more appropriate and inclusive. In some ways it felt like a choice, but it was a choice of whether you want to be 100 percent happy or 45 percent happy. Some people think gayness is like, you see another set of genitals and you’re like bleh, barfing. For me it was never that way.

Over the course of the memoir, Georges discovers how to be loyal to herself while choosing to be a caretaker for Beija. She explores and deals with the dysfunction of her childhood, and learns to be a better pack leader for Beija. Both she and Beija learn that, while strategies of self protection can be comforting, they can also be stifling. Throughout, Georges doesn’t shy away from drawing parallels between her own qualities and Beija’s, even when it’s sometimes the bad things that they have in common.

Fetch is a beautiful love letter to a pet, a coming of age story, and an exploration of all the complexities of what it really means to take care of another living being. At the end of the memoir, you remember that Georges bought Beija for her then-boyfriend, to heal his heart after losing his childhood dog; but it was Georges’s heart that Beija helped heal and grow, in the end.

saw this book at Flamecon! It sold out before I could get a copy, but her new dog did a great job entertaining visitors to the booth.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BX_YrBCFvI7/?taken-by=ponyogeorges

So cute! I got to ‘meet’ her new dog via Skype too.

This sounds like great read and also a great cry!

I picked up a copy of this book at FlameCon, and I’m pretty excited about it.

I love a good graphic memoir and I loved Calling Dr Laura. Thanks for alerting me to this!

Oh my. This is gonna make me cry

Yes, but in both good and bad ways.