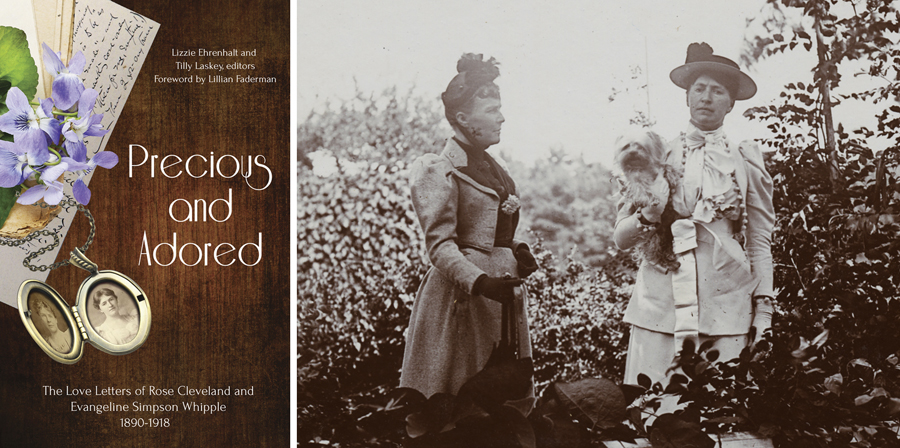

Left: the cover of Precious and Adored. Right: Rose Cleveland (left) and Evangeline Simpson (right) around 1893; Kingsmill Marrs Photographs, Collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

In my work as a public historian, I do a lot of thinking about the small actions that erase queer and trans history. Omitting a sentence from a book or an exhibit can have big results, amplifying silences and widening gaps in public understanding. The erasures we end up hearing about are usually public and dramatic; the straight-washing of queer icons in biopics, for example, has attracted a lot of attention over the last couple of decades, as has the failure of newspapers to mention same-sex partners in obituaries. Other times, however, our history is effaced in more subtle ways—with a gesture as small as, for example, taking a bundle of letters out of a box and putting it in a different box.

This is what happened at the Minnesota Historical Society in 1969, when library and archives staff removed a set of letters from a manuscripts collection because it suggested that two women had a sexual relationship. They weren’t wrong about that part. Rose Cleveland, a sister of President Grover Cleveland, fell in love with Evangeline Simpson (later the wife of an Episcopal bishop) in Florida over the winter of 1889–1890 and documented the evolution of their relationship in letters she sent over the next twenty years. (Disclosure: I’ve worked at MNHS since 2008.) Spooked by the potential for scandal, the staff placed them in a separate box, sealed it, and closed it to the public. The box remained sealed until 1978, when historian Jonathan Ned Katz heard about it via the Gay Task Force of the American Library Association and sent a letter to MNHS. Afterward, MNHS staff lifted the use restriction.

To further undo this erasure in the fiftieth anniversary of Stonewall, curator Tilly Laskey and I collected, transcribed, edited, and annotated the letters and published them in Precious and Adored: The Love Letters of Rose Cleveland and Evangeline Simpson Whipple, 1890-1918. Because I see Autostraddle as their spiritual home in the twenty-first century (seriously; Rose and Evangeline would have loved Vapid Fluff) I’m sharing a couple of my favorites here.

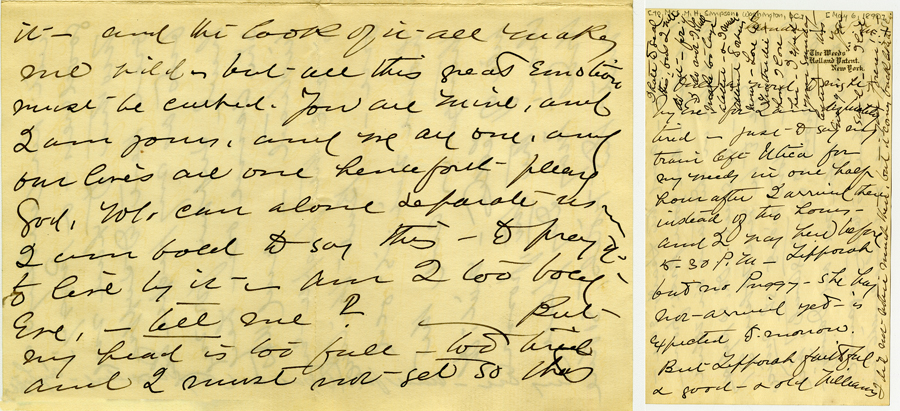

Letter from Rose Cleveland to Evangeline Simpson; Whipple-Scandrett papers, Minnesota Historical Society

The first letter is semi-famous among sexual historians for its description of two women giving each other an orgasm. (Really!) It is pretty breathtaking, and it’s one of the most explicit expressions of same sex-desire written by a woman that has survived from the Victorian period. But it’s the second letter, I think, that is most valuable as evidence of the emotional life of a woman who loved another woman in the 1890s. Anyone who’s been broken up with—but especially a queer person—can relate to Rose’s anguish as she pleads with Evangeline to reconsider her decision to marry their mutual friend, a seventy-six-year-old Episcopal bishop. (Okay, so maybe we can’t all relate to the bishop part.)

Evangeline went through with the marriage, and when she did, Rose wasted no time in planning a multi-year trip to Europe with a different mutual friend. Even then, she kept the letters coming, writing manically from Austria and Italy and Egypt as if to remind Evangeline, “I’m still here, and I still love you.”

The saga does have a happy ending, if a short-lived one. The bishop died, Rose and Evangeline saw each other more often, and in 1912 they moved to an Italian town called Bagni di Lucca. Rose lived out the rest of her life with the soulmate she’d refused to give up on, maintaining her characteristic mania until her death from influenza in 1918. Before Evangeline died, in 1930, she asked for a tombstone to match Rose’s, and she was buried in Bagni di Luca next to the woman she’d described as her “precious and adored life-long friend.”

Left: Rose Cleveland by Roseti, ca. 1890–1896. New Jersey State Archives: Department of State. Right: Evangeline Whipple by Roseti, ca. 1890–1896. Whipple-Scandrett papers, Minnesota Historical Society. Center: the matching gravestones of Cleveland and Whipple in the English cemetery at Bagni di Lucca, Italy, 2012; Ppoto courtesy of Tilly Laskey.

What do we lose when letters like Rose and Evangeline’s are kept from the public, even temporarily? A moving human story, for sure. Validation of queer experiences, definitely. But when you multiply this one relatively minor absence across all of the archives and libraries that have restricted “controversial” content, you also lose the totality of queer history.

The best way to fight this, I’ve come to believe, is to bring more queers and trans folk into cultural institutions. As librarians, archivists, curators, and editors, we can stop the erasure before it starts. We can lead projects that insist on queer and trans representation, as I hope Precious and Adored does. And we can put together a more honest, complete, and meaningful picture of history because of it.

Rose Cleveland to Evangeline Simpson, Murray Hill Hotel, New York City

Friday morning, May 9, 1890

Yes, I too woke before seven that Tuesday morning, and I think my first consciousness was of your absence—not presence. There is no such dear delusion possible to me, and it is only by your constant coming by letter, and all the dear words you can swear by, that I can be sure of you, Eve! A sad fact, darling, but a true thing. You must swear, Eve; take all the oaths you can to keep me easy: until I have you.

The photographs are before me. I wish to keep all of them, but not one of them shows me even your shadow, my Eve. My Eve is all light and joy and triumph, like a red rose just open on a June morning, with the look of one who has found, not lost—one who has reached and no longer seeks and searches earth and air for resting place. All these faces look other ways—either of sad loss, or sad search, or hopeless indifference, or dutiful effort, or proud acceptance of unlit days, all something except what my Eve looks into my eyes with brief bright glances, with long rapturous embraces,—where her sweet life breath and her warm enfolding arms appease my hunger and quiet my unrest, and carry us both in one to the summit of joy, the end of search, the goal of love! Here is no Beyond! Give me the looks of this Eve, and I will call it her shadow and it shall guide me to her, every inch of the long way, and keep me safe for her!

But this image will never get out of my brain; my Soul alone will give me back this reflection of the Woman who is my World—my Earth &—God forgive me—my Heaven!

Of all these pictures I like the Egypt the best because it looks least like you, and least unlike the Thou I claim. But I love these shadows of your former self, Eve—they are all full of sweet or sad significance, and if I put them in a book with a name they would be a history which I would call “The Makings of Eve.” But the last chapter would not be there. Well, send me another—that one I want—and let me keep what I have!

This Wednesday letter, with the yellow blossoms & the bit of flox from the old Washington garden, is in the same mail & records my first deliverance from our Weeds in awfully dear words of promise and love. Please remember, Madam, that I have a writing that can appear as evidence, if you do not fulfill your contract . . .

Ah, my Cleopatra here before me looks a very dangerous Queen—but I will look her straight in those wide open eyes that look so imperial, and will crush those Anthony-seeking [sic] lips with her army close over me (alas for my hair—not all those armlets) and she becomes my prisoner, because I am her captive!

4 P.M.

…

I have not been able to do a very driving business to-day, Eve. And only five letters beside yours show for my perseverance. I have had a rebellious “small of my back” which protests against such constant erection over this desk—and several times I have loafed off on this broad lounge, reading Browning’s Poems because they were in reach of my hand, & because you have them—or lying with my hands clasped under my head, as you do, thinking, oh, of course, of you—and seeing many visions of you in this room. Dear, dreamy, full-of-comfort Eve—will they come here?

I read your words over—for answer—“Yes, darling, I shall be with you, surely, in the autumn.” But the days will be long, Eve. They cannot be short—only I shall have to work while I wait.

There is an absurd rumor in New York that I am to be married—& people are writing & congratulating me conditionally. It’s very awkward for me to deny these rumors, Eve—what shall I do about it?

…

These are terribly long letters—I never dreamed I should wander on so, and still find so much to say—but I shall stop it after you sail, & only write, say, two sheets in a letter—to match “in a measure” yours. How much kissing can Cleopatra stand?

My love to Motherdie. I shall be so glad of King’s picture.

[Rose]

Rose Cleveland to Evangeline Simpson

summer or early fall 1896

Station 3:30 p.m.

Wingie,

I have been trying to find just the right thing to say—but nothing comes. The right word will not be spoken. A frightful storm may just come—and in the greatest hurry I have got to this station an hour before the time, lest if I waited I could not come at all.

A newspaper reporter has followed me from the hotel, where he blocked my way & was repeatedly refused but waited hat in hand, following me, standing before me, though I say over and over that I will [sentence ends here]

What is yet for us I cannot see. But I think you will need me yet—in a future, perhaps. I do not think you need me now. But I plead that you will consider what I said this morning. I will give up all to you if you will try once more to be satisfied with me. Could you not take six months for that experiment? We would go away from everyone.

I wish for your happiness and good. Think what I said this morning, and do not decide hastily that there is only this one way. Remember our Florida.

If—after all—there is but this way for you—if you will do this thing—then I will not stand in the way. That means that I will study only for your comfort and pleasure and happiness. That will mean to take myself out of your way—for awhile, at least—and to reappear only when I can act gracefully and well in my new role.

Do not dream that I blame you. Never—never. However, it should have been my due to at least have known the danger. I have guarded against it—however much I would blame another who to another did this—never, when it is you to me. It is too deep for blame because it is all too deep for comprehension. The pain, the strangeness, the surprise, the wrench, the hurt, the wonder. There is no fright about it now.

I do not know whether it is I who understand or you. Perhaps we neither of us understand each other.

I cannot write. It is nearly time for me to leave. God bless you—you can depend on me.

Rose

[written on back of last page:]

I cannot speak nor write of my love. You know——.

Thank you for your work. Our queer history is rich and vibrant and makes me so fucking proud

You’re welcome. It makes me proud, too.

This is wonderful! Thank you for your work bringing these women to our attention!

P.S. just ordered a copy

Hi this is Lizzie’s wife and I’m just so happy that she got to write an article for autostraddle!!!!!!!

Bless public historians! This is a wonderful find!

“I cannot speak nor write of my love. You know——.”

…brb, gotta go stitch my heart back together

Right?? This is one of my favorite things about historical documents like this; so much of our lexicons and styles have changed, and then you hit a moment like that and just go Oh, I *know* this.

I’m not one to romanticize the past, but Victorian letters between women make me feel like we’ve lost something as a society

…or maybe it’s just that I have the expressive talent of a slug lol

I live in a town with a lot of Grover Cleveland descendants, I’m going to suggest to our library director that they purchase a copy for pride month! Love this whole thing (well except for the dying from influenza part).

That’s great; I appreciate it.

Amazing, definitely going on my to-read list!

I immediately ran to the library catalog and downloaded this from Hoopla. It looks fascinating and wonderful, and thank you for this article! I wonder how many more sealed boxes about other people are out there–though I’m sure lots went up in smoke.

“Omitting a sentence from a book or an exhibit can have big results, amplifying silences and widening gaps in public understanding.”

This resonated with me so much, and it hurts.

I’m working as a tour guide in a restored house that was just FULL of queer artists. The organisation is very cishet and only in the last 3 years or so has started emerging the queer history. The other guides are older women, many of whom have worked there for 5+, 10+ years, and were told earlier on that the public would not tolerate too much detail about the queer aspects. We have a basic script but each guide makes it their own, and this means it is so easy for the queer elements to be completely or somewhat erased depending on the tour.

Also, we recently launched a new, special ‘queer tour’ (with barely any queers involved in the writing of it).

I have too many feelings, honestly. I’m so frustrated and upset knowing that a guide could erase the queer stuff when it is so important for us to feel seen, to feel belonging in history. I am upset that the queer tour is a special tour, not the regular one. I know it comes from a fear of upsetting the mostly older, richer public or the families who visit. I feel a deep desire to change things but I don’t know how to. I know this is just the symptom of an organisation whose commitment to queerness is mostly performative and it kills me.

If anyone has any encouragements, strategies or wants to talk about this I’d love to.

Yes! I’d love to chat about this. I am experiencing similar questions at my historic site.

This is wonderful, thank you for bringing it to us!