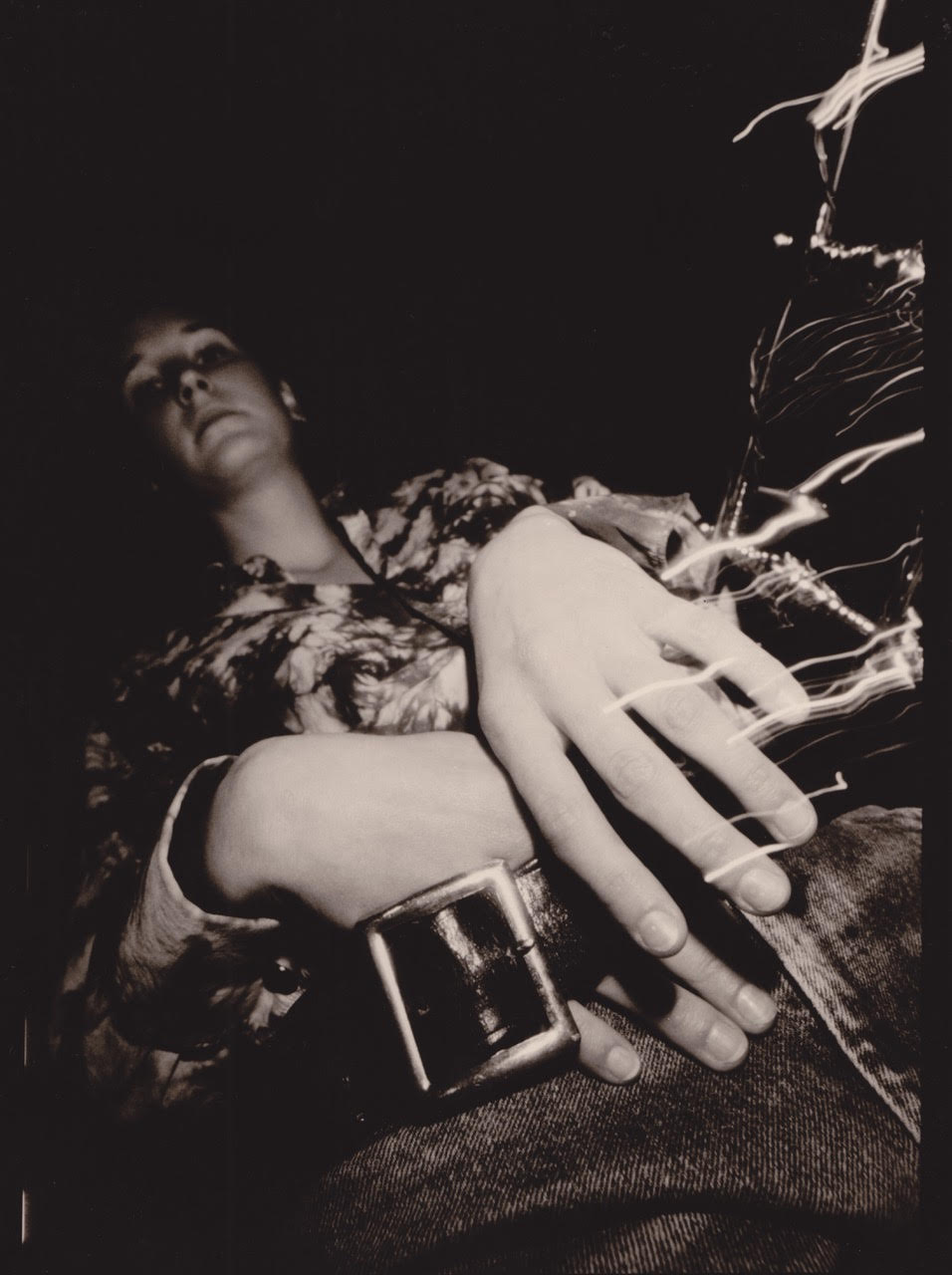

feature art: Autostraddle // photo: Phyllis Christopher

Phyllis Christopher’s Dark Room merges queer sex and protest during a tumultuous time. In the late ’80s, Christopher left her hometown of Buffalo, New York, and headed to San Francisco, where she captured powerful images of ACT UP marches, Queer Nation kiss-ins, S/M, drag kings and a queer community in flux. Phyllis also became a contributor and photo editor at On Our Backs, an erotica magazine that proudly bore the tagline, “entertainment for the adventurous lesbian.”

Dark Room is a gorgeous collection of Christopher’s black and white photographs taken between 1988 and 2003. The book also includes writing by Susie Bright, Laura Guy and Michelle Tea, as well as an interview with Shar Rednour. I chatted with Christopher about Dark Room and her experience documenting San Francisco’s flourishing lesbian culture in the late ‘80s and ‘90s.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Ro White: Can you tell me a little bit about your artistic background? And then what drew you to documentary photography and erotic photography?

Phyllis Christopher: I did photography from the age of 12. It was kind of the way I dealt with the world. And it got me through a lot of social events, especially family events. I picked up the camera and never really put it down. I got a BFA in Buffalo at the State University of New York there. I was living in Buffalo, which was really not the best place to be. It had a good queer community, a very supportive community, but it was small. And I visited San Francisco and just realized I needed to be there, especially when I was young, and I just got in a car and went with a friend. We didn’t know anybody, and it was just the best adventure ever. And it was a period of a real critical mass of women, especially the lesbian community, coming together and really wanting a voice, really wanting to develop our culture and show our culture.

I’ve spoken about this a lot — it was at the height of the AIDS epidemic, so, late ‘80s. It was a terrible time for all of us. We were watching our friends die. The women’s community was sort of having to be strong and develop a voice out of that grief. We were really partying hard and having to demonstrate constantly. One of the reasons I was interested in photographing sex was, for one thing, no one ever talked about lesbian sex in the mainstream press. So we wanted to communicate and develop a language and educate each other. It was also a time when you had to graphically talk about sex. People were dying because they were having sex, and the government, the doctors — no one was telling us anything. We were learning new things every day, and we had to communicate it. It became necessary to be very graphic.

Ro: And you were still living in Buffalo when you sent your photos to On Our Backs — is that right?

Phyllis: Yeah, I was working on a series of unusual nude portraits. I started photographing myself to explore my own body image, and then my friends saw them and wanted to be photographed themselves, which has always blown my mind. I’m not an exhibitionist — I started out photographing myself as a challenge — but exhibitionists are what make the work, because they love being photographed, and it’s a back and forth relationship. So I started photographing my friends running around naked. One of my friends in Buffalo who was really into S/M and leather said, “Photograph me in my attic,” so we did this sort of dark, leather spread. I sent it to On Our Backs, and they loved it and published it. It was definitely one of the reasons I moved out [to San Francisco], because On Our Backs was the only thing. There was obviously no internet. This was the only way to communicate about sexual education or entertainment or lesbian culture.

Ro: It seems like the people you photographed for On Our Backs were willing to do that during a specific time, before the explosion of social media. Do you think there’s room for erotic photography on the internet right now?

Phyllis: Well, I see a lot of great things on Instagram, a lot of great lesbian erotic work. I don’t think my work would have happened if we had internet. It was an era when you could lose your job or your children for being a lesbian. We’d all lost our biological families. People felt safe in that bubble of San Francisco and in the confines of who they thought was going to look at the magazine, so there was a lot of freedom. I had an understanding with my models. First of all, it’s a collaboration, and we had an understanding that nothing would [be published] unless they liked it. They got to see the proof sheets. But yeah, I think there should be real lesbian erotica on the internet now, because what I’m hearing from young women is that if you Google “lesbian sex,” it’s all this straight crap, which is really depressing. I’ve also been hearing from young women that they need something like On Our Backs right now. And I was shocked. Maybe ten years ago I started hearing this, and I was like, you gotta be kidding me!

Ro: I know that On Our Backs was controversial, even within the lesbian community. Can you talk about that?

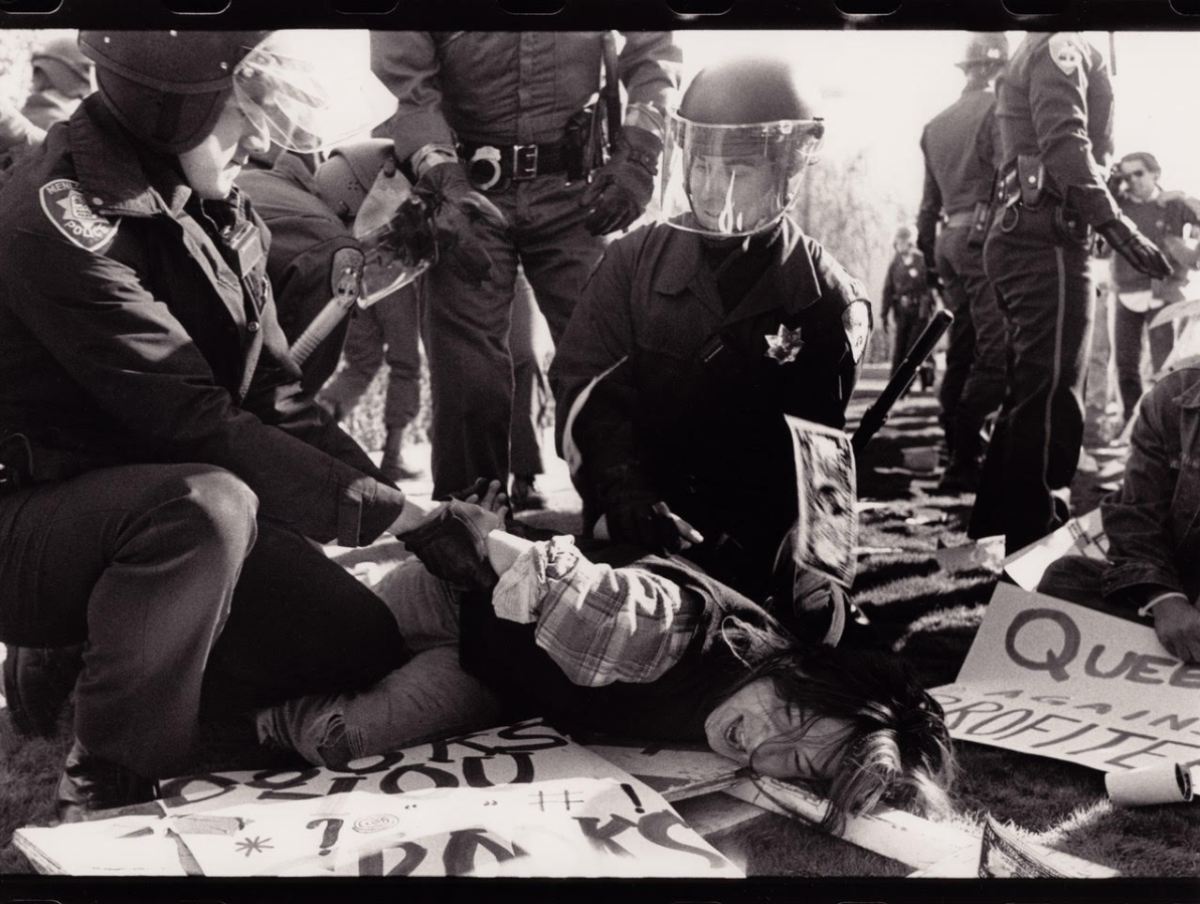

Photo by Phyllis Christopher

Phyllis: Yeah, it was one tool. We were trying to please everybody. I worked as the photo editor for a few years, so I got to understand the magazine business from that small perspective. There was a lot of division in the lesbian community. There were people who felt like portraying sex at all was misogynist and to photograph a naked body of a woman could not be done in a respectful way. It was objectifying the woman. And I was in the other camp that said, “No, we need to take the power into our own hands. We need to photograph each other and really empower ourselves sexually by doing this.” On Our Backs tried to appeal to everybody because it was the one thing we had, so they would have very vanilla sex, they would have S/M sex. They were open to publishing anything that they thought would speak to various parts of the community, so it inevitably pissed other parts of the community. It’s the most entertaining thing to look at the letters page because someone’s always mad about what was previously published. “There’s not enough of this. There’s too much of this.” No one was ever happy.

Ro: I think that’s true for any queer media published in any era. It’s certainly true right now. You took the photos that are featured in Dark Room between 1988 and 2003. Was this publication a long time coming? Is there a reason why you wanted to put this out now?

Phyllis: I always wanted this body of work to be a book since probably the late ‘90s, and there was no publisher interested in it. Nobody really understood it. They thought it was either frivolous to photograph sex, or it didn’t appeal to them. What actually happened was about five years ago, I started getting phone calls and people visiting my house. I’ve moved to the north of England, to a fairly small town called Newcastle, and ended up bringing my whole archive with me. And more and more PhD candidates, students, young women artists were wanting to see my archive and talk about the work, and I realized in academia, they’re very interested in this era right now, starting in the late ‘80s, to look back at the politics. So it sort of became the right moment to publish it. I thought, well, let’s see if there’s an interest, and I did get interest. I was lucky. I met Book Works — that’s my publisher — at a book fair, and they got it. They understood that the street protest photographs worked with the sex photographs.

Ro: Can you say more about why you chose to show the protest photos alongside the sex photos?

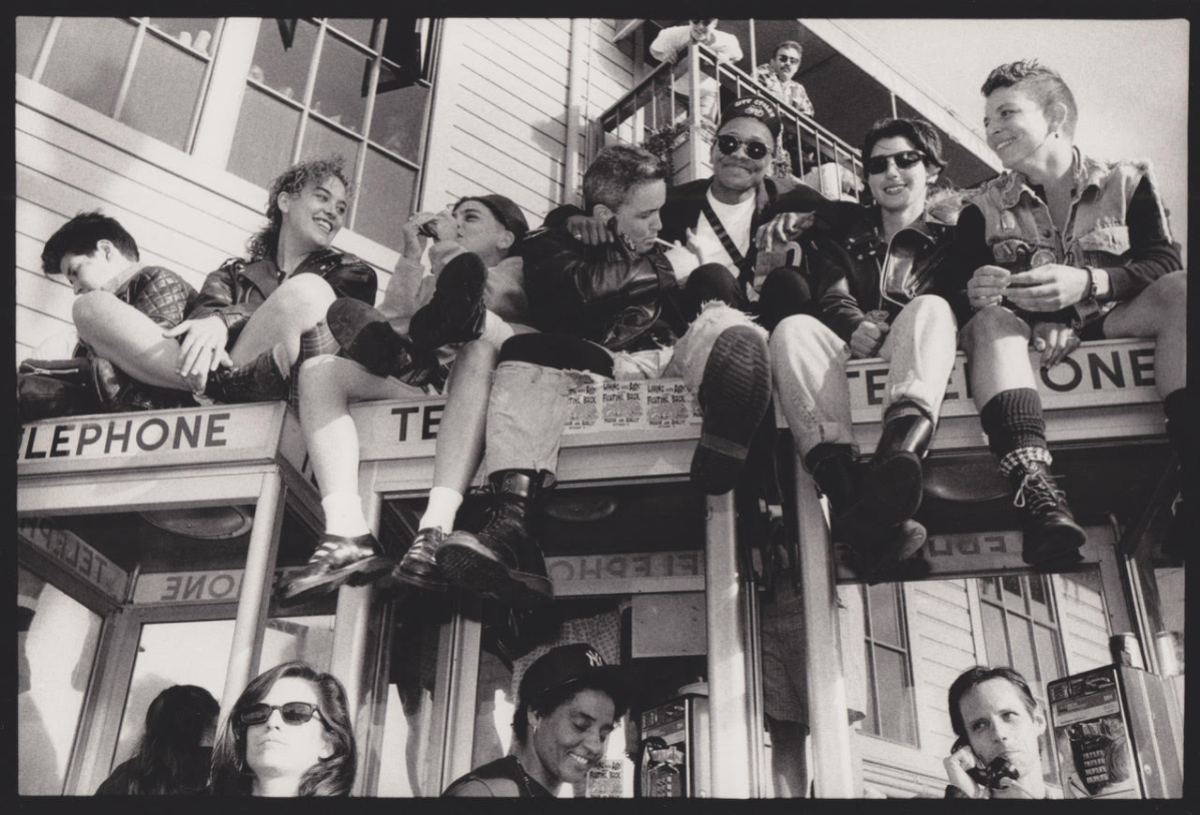

Phyllis: It was sort of like a day in the life, you know? That was the era. It felt like there were constant protests — maybe a couple a week. We were out there protesting for more medication. There were ACT UP protests. There were Queer Nation sit-ins just for visibility. You could start a riot by just kissing someone of the same sex. It was just a very fun and vibrant time. So that was the daytime atmosphere. And then there was this real vibe in the lesbian community — women were desperate to be photographed because they weren’t seeing themselves anywhere. It was not hard to find people who wanted to be photographed, and On Our Backs was the outlet for it. And everyone was very political. It was a political statement to portray sex, to portray queer sex, as it was to demand civil rights in the daytime.

Ro: You must have a massive archive to choose from. How did you choose the photographs for Dark Room?

Phyllis: We decided that it should be darkroom-based, that it should be black and white film-based. Because frankly, that’s my favorite work. We went with my favorite images. I’m a black and white photographer, primarily. So then the book was called Dark Room. These have been my favorite images for twenty years, and so it was like the baby had to be birthed. I have time here and there to look into the archive at the outtakes and the color work and all of the other stuff, and I’m finding that really interesting. There are all sorts of other stories happening because I’ve kept almost everything I was able to transport. I shot a lot of book covers and photographed artists and writers. Then I did digital work, which has a slightly different feel.

One point about the black and white work is that it was very private. One of the reasons why I like black and white is I had total control over it. I would go home and develop it in my kitchen sink. The models would come over and see it in my house, and they knew it wasn’t going to be seen in a lab or get censored by somebody who was uncomfortable with it. And that’s not true with color work — you usually have to send your color work out. So the black and white work has a certain intimacy to it.

Ro: You have a history of showing your work in some non-traditional spaces. I know you’ve had shows at Stormy Leather and Good Vibrations. Why did you choose to do that? Or were you forced to do that because of the nature of your work?

Phyllis: To this day, art galleries aren’t really comfortable showing very graphic work. Until a couple of years ago, the art world seems to have found an interest in this work, and I’m just really happy it happened before I died! I just feel really lucky. I love this work. I wanted to have a book out there for other people, for other women to have access to it. I didn’t have any aspirations to be in a fine art gallery, or I just didn’t bother. I mean, they would have just said no, and it wasn’t until 2019 that the Still I Rise show in Nottingham asked me to put only the protest photos in. And I was so happy about that. That was sort of the turning point. I thought, wow, now people are looking back at this era, and they value the protest photos. Because before, I would be in group shows with straight sex photographers, and it was just a sex-based thing. They only wanted to ever see the sex stuff. So that was a turning point, and then after that, I thought, I really want these combined because they make sense together. They fill out the whole picture.

Photo by Phyllis Christopher

Ro: There’s one series of photographs in Dark Room that I want to know more about — the photos of women peeing in the street! Was that something the models initiated?

Phyllis: The pee series started in the late ‘90s and went on for about four years or so. I couldn’t believe that my friends were having a good time peeing for the camera. But it’s really liberating, especially for women to stand up peeing in public spaces, because we never do. We’re always hiding.

It happened by chance. This amazing friend of mine named Ivy was posing for some photographs we were doing for a video documentary, and she needed to have a pee break. So the whole crew turned off the lights and everything, and then she turned around. And I was thinking the same thing. She said, “Don’t you want to photograph me?” I was like, “Yes!” So I photographed her, and I really liked the photos. She liked them. And it just set a whole new project going. Friends would see them. Other women would see them. We would pick different locations, and we continued down that line. I just thought it was very sexy to see this outward portrayal of a woman’s power — of a woman doing something like that in public and feeling really good about it. It was a lot of fun.

Ro: It seems like much of your work focuses on lesbian signifiers — the visual language that queer women were building at the time to identify each other. In what ways have you seen that visual language change over time and in what ways has it remained the same?

Phyllis: Yeah, it’s something I’m still interested in. There are still things that are the same. My friend Jade Sweeting is photographing lesbian semiotics right now. She actually curated a show that we were all in that started the ball rolling for the book and everything. But she’s also interested in that question. She’ll photograph keychains — you know, keys on a ring on someone’s belt.

I think younger generations possibly present themselves — perhaps there’s much more subtlety, and there are many more choices, which is wonderful. My era was very butch/femme, and not a lot of gray areas, maybe? I think in America there are still flannel shirts, aren’t there?

Ro: Oh, yeah. I can personally attest to that. Tell me about the writing that’s included in this book.

Phyllis: It was my dream team. I wanted everyone to bring their different perspectives. I wanted to just have a conversation with [Shar Rednour] as someone who I worked with on the magazine. And then Susie Bright, who is an amazing writer, who I always turn to for inspiration and knowledge — I wanted her perspective. And Michelle Tea is one of my favorite writers, and she was [in San Francisco] at the time. And then Laura Guy, who’s an incredible academic and who worked so hard on this book — I can’t say enough about what she’s done as an editor and photo editor. I wanted her academic historical writing in it. So I think it rounds it out very nicely and gives people perspective from various different angles.

Ro: Is there anything you’re working on right now that you want to talk about?

Phyllis: Mostly, I’m busy promoting the book. However, I’m looking at a grant so I can tell more stories from the archive. I really would like to go in there and see what other narratives are going on, because I photographed pretty much non-stop in San Francisco. I would photograph parties. I was doing a lot of magazine photography of writers and poets. So I want to go back in and look at the idea of queer family, in the sense of who were, who I consider my family, who supported me at the time. And I’m interested in comparing it to my nuclear family now, because I’ve adopted a son with my partner, and I’ll develop that perhaps as a show.

Photo by Phyllis Christopher

You can purchase Dark Room through Book Works. A US publication date is TBA.

Amazing interview and amazing photographs! Would love to read more like this

Delurking after years to say how much I appreciate the 80s coverage and especially this article.

I lived in SF in the late 80s, in a flat full of lesbians and our lovers, and On Our Backs was always around. After growing up with exactly zero information about lesbians I loved the honesty, variety, and affirmation of OOB. It made possible a lot of necessary and empowering conversations. The DIY, “we’re making and taking our space” vibe was intensely creative. I see Autostraddle as right in line with that history.

Also, adding a yes to the flannel witness. Flannel then, flannel now.

“I see Autostraddle as right in line with that history” is SUCH a high compliment! Thank you so much for this comment!

Why I read Autostraddle nearly daily!

Please stay and comment more! I bet I’m not the only person on here who’d love to hear your perspectives

Thanks, I’m feeling old in a good way now.

This was a great interview, thank you!

This was amazing! Just ordered my copy! Can’t wait!