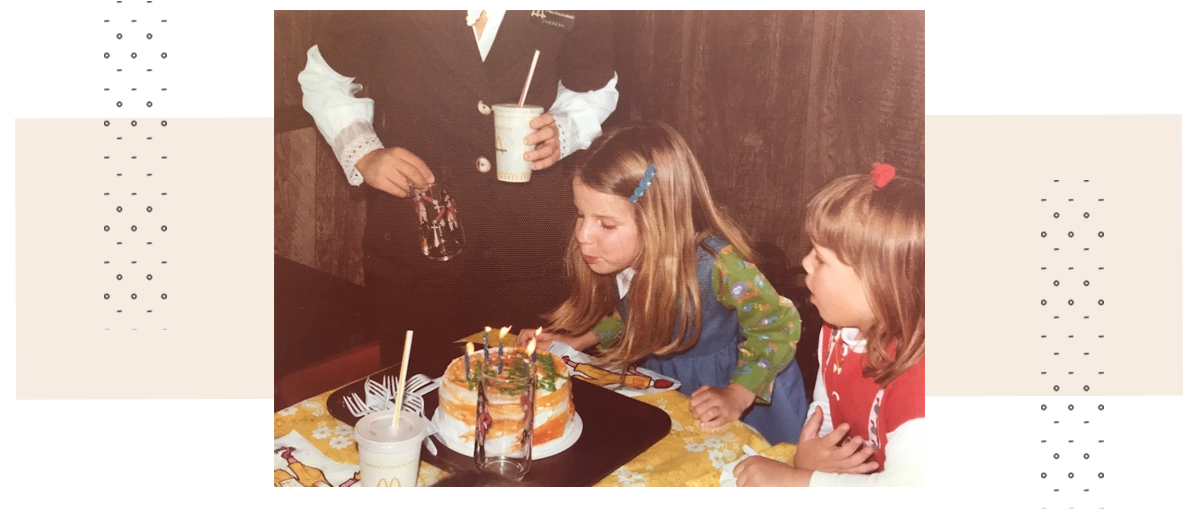

I always thought the date of my birth was cool. June 12th. The day itself often wasn’t all that remarkable. Maybe it’s because there aren’t a lot of photos from my childhood, no visual anchor, no placeholder for these events that lacked any real distinction from the multitude of birthday celebrations I have attended over the years or the thousands of other days I have lived so far. I can remember the feeling of being plunged down the water at the Family Fun Center slide, my skinny sunburned body flung so far up that I was certain I would go over the edge and fall 40 feet into the parking lot below. That’s what imprinted, that mix of terror and excitement that I can still sense in my body today.

June was Gemini season, and Gemini was the sign of the twins. A doubling of what was meant to be single. I didn’t have an actual twin, but for much of my life I would either feel as if I were two different people or that I was only one half of something whole.

![]()

Julia shared my birthday. She and her family — all of them blond, tanned and athletic — materialized at the neighborhood pool one afternoon when I was nine or ten. There weren’t many kids nearby so it felt magical that this beautiful Gemini girl would show up out of nowhere.

We became best friends, in the way kids so easily do when their ages and physical proximity make it convenient. We became inseparable. The minute I got home from school I changed out of my uniform into play clothes and ran down the hill to show up, breathless, at her door.

I loved hanging around at Julia’s house. She was more worldly than I was, having moved around a bit and gone to public schools. Her mom, Katy, wasn’t like the other mothers. She didn’t shave her legs or wear a bra. She was an outspoken feminist, a woman who had armed her daughters with proper information about things like equal rights and anatomy and sex.

Julia and her family seemed to fit in with the world in a way mine never could. I wanted us to be just like them; I wanted to be sure of who I was and where I belonged. Julia was comfortable in her body, confidant in her movements. These were traits I longed for. Everyone seemed to love Julia.

Everyone except my father.

I think it must have been Katy’s outspoken liberal views that eventually caught his attention. She was pro-choice, she believed young women should have free and easy access to contraception and she wasn’t afraid to say it. This was a direct affront to everything my father believed. He started to forbid me from seeing Julia, telling me that because her family wasn’t Catholic they were going to Hell and I didn’t need to waste my time on people who were going to Hell.

I was confused. Can’t people get baptized at any time and get forgiven for their past sins and still go to Heaven? This is what I had gleaned from the teachings so far. It didn’t matter what you were before; anyone could be saved. Of course, you were supposed to live in accordance with God’s laws, but there was room for error. Ours was a religion where confession was redemption, humility and a dash of holy water equalled salvation. Theoretically you could sin nonstop all the way up to the very moments before your heart stopped and your soul left your body. And if a priest arrived in time to deliver last rites, if you repented, you would appear in front of God for your final judgment and be found worthy of spending an eternity in His loving arms.

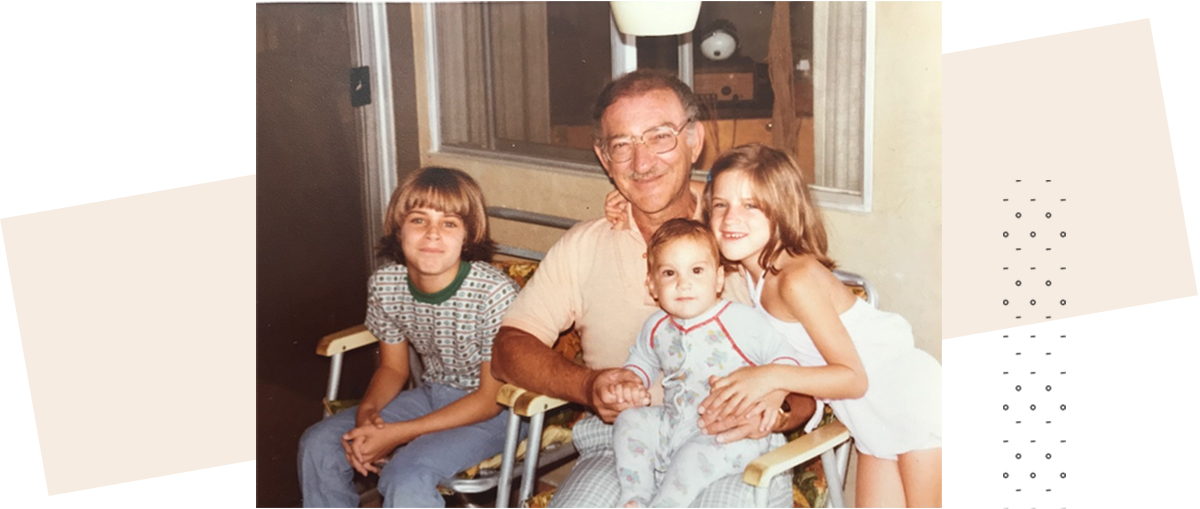

I knew this because my father was going to Heaven, and he hadn’t gotten baptized until college. He was raised an Orthodox Jew, the only child of Victor and Dorothy. Mel was an exceptional student, a kid genius, a tall handsome science nerd who built a crazy contraption in a high school physics class that smashed atoms. He won a national award for that, got a little feature with a photo in a prominent girls’ magazine. He had been groomed for rabbinical school, and went to NYU against his mother’s protests. It was there that he would meet Mary Alice, a brilliant, beautiful Catholic girl.

He began taking Catechism classes and proposed to my mother. They had a quick civil ceremony to keep him from getting drafted and planned a proper church wedding for once he completed the process of his conversion.

It has an air of the romantic, doesn’t it?

Mel had been carrying this enormous familial responsibility of being the only child, a son, of a Jewish mother. Her entire world, the entire world, revolved around him. He hadn’t chosen this life, a life that would keep him from being with the woman he loved. But becoming Catholic, this was the way forward for him.

He would be saved.

![]()

My grandmother refused to go to the wedding. She didn’t belong there, she said, she wouldn’t step foot in a church. She was hurting, embarrassed. Full of shame and anger. Dorothy would never accept that he had chosen this girl over his faith. That he could just turn his back on her and everything she had raised him to be. She could barely speak to him.

But once the grandchildren started arriving, first my brother, then me, she was back in their lives. We were babies, after all, and we bore her name even if we would never be properly Jewish. My mother put up with the hour long daily phone calls, brought us for weekly visits to the house on Shore Parkway.

Dorothy had opinions on every aspect of child-rearing, demanded to know our feeding schedules, how we were napping, the consistency and frequency of our bowel movements. My mother accepted the endless pieces of unsolicited advice, primarily with grace, as young mothers of her generation and upbringing were taught. But Mel didn’t want his children to have this Jewish influence; he didn’t want to have to negotiate the difficulties of trying to integrate these two opposing parts of himself. He needed space from his past. By the time my second birthday rolled around he had moved us across the country.

Away from his mother he had the freedom to identify as Catholic. He would never take his new religion for granted; I think he felt as if he had to work harder to prove that he belonged. He changed his name to James and was ordained as a deacon. He stood in his vestments every Sunday, distributing Holy Communion and sometimes preaching the homily. To me, he was special, appointed to be one of God’s representatives on earth.

His dedication extended beyond the church doors. He became the editor in chief of the diocese newspaper. He visited the sick and the elderly. He spread the Word. He wanted his children to emulate this quality of Christianity, too, and when it came to what my father wanted, there was no room for negotiation. He insisted that we hold ourselves to higher standards than any of our friends and neighbors. Everything we did, said, wore had to be in line with our religion.

I loved being Catholic. To me it meant a childhood exploring the enormous mysteries held in the many alcoves and nooks and stairways of the cavernous Immaculata . This church, the university library, and the surrounding lawns and rooftops were my playground.

My father didn’t talk much about how he was raised; questions about his early life were answered vaguely or not at all. The stories he shared were a carefully redacted mix of his academic successes and accomplishments. He didn’t offer up any clues to his past in our community either. He was cautious and controlled about his image. Despite his role in the clergy, he was difficult to get to know, and he didn’t form many close bonds. It was as if he forever needed to hold people at arm’s length, lest they find out his truth.

I didn’t know that my father had ever been anything other than Catholic until I was sent off to Brooklyn on my sixth birthday to spend a sweltering month with Dorothy and Victor in the house where he grew up.

It was my grandfather that met me at the airport that June afternoon and I loved him instantly. His eyes twinkled in the way that Saint Nick’s did in one of my Little Golden Books. Victor’s belly wasn’t big and he didn’t have a white beard, but he gave off the strongest Santa vibe of anyone I had ever met. He swept me into a bear hug and pulled a silver dollar from my ear.

Dorothy couldn’t have struck a stronger contrast as we drove up and I saw her on the front stoop, her arms folded across her ample bosom. She stood squarely in her flowered housecoat, her hair set in tight curls. She didn’t smile while she looked me over. She commented on my thinness and wondered aloud what my mother was feeding me. She inspected my nose from every angle. Once she was satisfied with what she saw, she softened a bit and hugged me. There was even some cheek pinching, along with promises to fatten me up.

She led me into the house and before I got settled she wanted to go over the rules. Most of them had to do with food. She had the same level of intense interest in my cycles of ingestion, digestion and elimination as she had when I was a baby. But there was one rule in particular she said that was very, very important for me to understand.

I was not to talk about religion under any circumstances. Not to her and not to anybody else I might encounter while I was visiting.

As far as she was concerned, I wasn’t Catholic, but I wasn’t Jewish either. I had no religious identity. I was just a girl who didn’t go to church and didn’t go to synagogue. I didn’t have to make up elaborate stories, she said, I just shouldn’t talk about it.

“If someone asks you where you go to school,” she warned, “Do NOT say the name. Just say you go to the neighborhood school.”

Being a Catholic was everything to me. It wasn’t just church and school, it was all of my friends and the clothes I wore. It was the only thing I knew, the container in which all of my experiences were held. I didn’t know how to not bring it up unless I didn’t talk about myself at all. Plus it was lying. And lying was wrong.

I felt ashamed. I felt like it hurt her to look at me. And I really had no idea why. My stomach started to ache. I wanted to go home. As she toured me through the house, there were pictures of my father everywhere, as a baby, as a toddler in short pants and a cardigan sweater, as a boy at temple, as a teenager celebrating Hanukkah. His room was packed full with his science awards, his collection of Mad Magazines, the pantry full of his favorite foods.

Later that evening we all sat outside and looked out over Gravesend Bay. My grandfather had his arm around me as he pointed out fireflies, which I had never seen before. I was homesick, but Brooklyn seemed mysterious and exciting to me, and so did this house full of secrets. As it grew darker Dorothy went in to grab us sweaters. Grandpa leaned over, winked, and pulled a couple of quarters from my ear.

![]()

It was surprisingly easy for me to follow my grandmother’s directive that first summer. I was a rule follower, continually filled up by the accolades I received for getting top marks on exams, by exceeding expectations. I thought God would understand my situation, would forgive me my trespasses. My grandfather was so much fun; we were having incredible adventures in the city, it made up for the discomfort I felt about how my grandmother looked at me. I threw myself into being this in-between girl, the one who wasn’t either. It was easy to pretend to be someone else when I was so far away from home.

But I was curious about Judaism now, what it meant and why my father had rejected it. Somehow what he had done had put me in direct opposition to it, and to my grandmother. She had forbidden me to talk about religion and any attempt to broach the subject with my dad was shot down. His anger was quick when it came to Dorothy, to any reference to the fact that he hadn’t grown up Catholic. I had already learned that it was better to not anger him. His word was always the final word.

I don’t know when I first read Anne Frank’s diary; I devoured books when I was younger and like birthdays, I’ve run out of ways to hold onto to all of the details surrounding each one. But I do remember laying on my stomach on the shag carpet in our living room, sunshine warming my back through the big picture window. I remember opening to the first entry and reading her words: “On Friday, June 12th, I woke up at six o’clock and no wonder, it was my birthday.”

Another birthday twin, a Jewish girl who found solace in her writing. I read her words over and over, horrified at what she went through. Looking for some way in which we might be the same.

I wasn’t Jewish, even though by now I knew that my last name was. And it seemed that somehow I was tainted by this thing that didn’t really belong to me. Why would my father deny it so strongly? Why would this girl who shared my birthday, who could have been me in a past life, why would this girl have to hide away in an attic to try to stay alive?

And what was it about being Catholic, about my Irish half, that made it impossible for my grandmother to love me as I was?

It seemed better to be one or the other, to sit at a polarizing end where there would be some people that might accept you. But instead, I was caught in the middle, my DNA mixing into something neither side wanted to claim.

As I grew up I continued to live in that in-between space. I would reject my faith and refuse to get confirmed; I began challenging and then rebelling against the dogma that was continually being forced on me. I lost interest in what it might mean to be Jewish as well. This thing that had caused so much pain and hatred — it just became easier to deny it was part of my ancestry.

Being a Gemini took on a new meaning for me. Inside I was two girls, one half-Catholic, one half-Jewish, but not identifying as either. I would jokingly offer up my astrological sun sign as an excuse for my own bad behavior, maybe as a promise, a warning, that you might get more than you bargained for. “Who, me? I’m a Gemini,” I would smirk over a beer, “Both of me.”

![]()

I carry that generational wounding deep in my bones. Like my father, I spent a huge part of my life self-isolating to stay safe from exposure, forever conscious of what version of me might be expected to show up in any particular situation. I was better at the social stuff than he ever was, but I still struggled to be okay with myself, to make connections that felt genuine, easy.

Writing has become my refuge again, a place for me to find and then practice using my voice. I think about Anne fearing for her life in the attic in Amsterdam, with only her words to comfort her. I think of the six million Jews who died because of small-minded hatred.

I think about Julia, too. The night she snuck in to say goodbye and how she hid in my closet when he unexpectedly came home. How she fled from my house because he frightened her and how I chased after her down the short wooded path that led to her street, and held her under the trees were we had shared our secrets. I had loved her because she I thought she was whole.

And I see, finally, that I am whole. I wasn’t ever half, or two. These weren’t fractured pieces that didn’t fit together. Once I cleared those voices that had become the architects of my negative self-talk, once I allowed my true self to come out, first through my diaries, and then to the people around me, I started to see who I really was. Not broken, but a strong and beautiful blend of heritages and experiences and and my own queerness. A unique blueprint that I could finally love.

![]()

My father died this summer. He hadn’t spoken to me in over 20 years. He didn’t like the version of myself I was becoming, and, like his own mother, found it, and me, unforgivable. But unlike her, he couldn’t soften enough to try to be part of his grandchildren’s lives. I had just started to forgive him, not for the cruel words, not for being absent. But I had gained some perspective on what it was like to have a secret that caused crippling shame, how conflict is so much about misunderstanding, about unwillingness or inability to see things from someone else’s perspective. And how those things can begin to feel insurmountable over time. I knew how it felt to not be seen, to not feel like I fit in anywhere. I think that is something we shared, like our love for writing and photography.

I don’t really know much about how he lived the last part of his life, but it wasn’t with the same vigor for Catholicism he’d had when he was younger. He stopped going to church after my mother left him, got married on a beach somewhere to a Jewish woman with a lapsed faith of her own. They traveled, he collected art. He slowly distanced himself from all of his children.

A few weeks after he died I received a copy of his documents from the trustee. I knew I had been disinherited, but nothing prepared me to see it in writing, to imagine him sitting in his attorney’s office, giving him my name, directing him to expressly leave me nothing because I had had “little contact” with him for many years. My father had spent the last few decades denying that I even existed. But legally, I was still his daughter and I had to be mentioned or I might claim the rightful portion of the money my grandparents had always intended for me.

But in those papers he got my birthday wrong. He got all of our birthdays wrong. In an ironic twist that is not lost on this Gemini, he made me and my substantially younger brother twins. My father was not a man who made sloppy errors. The mistakes confound me. Are these inconsequential details to him? Evidence that he really had just erased me as thoroughly as he had his own past? Or was this one last attempt to remove the real me, my very birthright, from his narrative?

The estate was substantial. He had invested Victor and Dorothy’s money well. He left his two sons each just a few thousand dollars.

Everything else goes to the Catholic church. 🎈

edited by rachel.

Comments

Wow, Bettie. Former Catholic here sending you all the hugs. Peace be with you.

Thank you. xo

Bettie, this is a brilliant and absolutely stunning piece of writing. I will be thinking about it for a long, long time.

Thanks for your kind words, Heather!

Oh,wow. Thank you for sharing this with us.

Thank you for reading it.

This was amazing, thank you so much!

Thank you!!

Wow geez—so much in here. Wonderful storytelling

Thank you, Ashley!

Wow, this made me feel things. Thank you.

I was raised, and still am, secular. My mother had Jewish ancestors but was also raised secularly. My dad left Christianity, and I can feel the tension with his side of the family, interwoven with history of my dad’s previous marriage.

Thank you for reading and sharing a little bit about your own experience. I’ve had quite a few people reach out to me this week about their own family situations where religion has created tension and discord. It seems to be a theme people can really relate to.

Beautiful, thank you

Thank you!!

This is a very beautiful and careful piece of writing. Your description of having to not talk about your faith when visiting your grandparents is similar to a story my grandmother told me about her childhood. Her mother was an Irish Protestant who had married an English Catholic and converted, so my gran and her sister were raised Catholic. Every summer they went to stay with their mother’s relatives in Ireland, but their mum never told her family she had converted. My gran didn’t really go into it, but I presume they were also under instructions not to talk about religion. I think there was definitely a similar pain there about knowing that there was this separation but not understanding it.

Thank you for your kind words and for sharing. My Irish grandmother (who doesn’t make an appearance in this story) certainly had strong opinions about both the Protestants and the Jews, but thankfully I didn’t pick up on much of that until I was older.

There is so much here and I’m still trying to unpack even a little bit of it. It’s amazing you got this out, thank you for sharing and just wow. wow. wow.

Thank you so much!

As a raised-Catholic Jew, this whole essay has settled deep into my heart. Thank you for writing it.

I’m a preacher’s kid. My partner has one Jewish parent, one Catholic.

This filled me up.