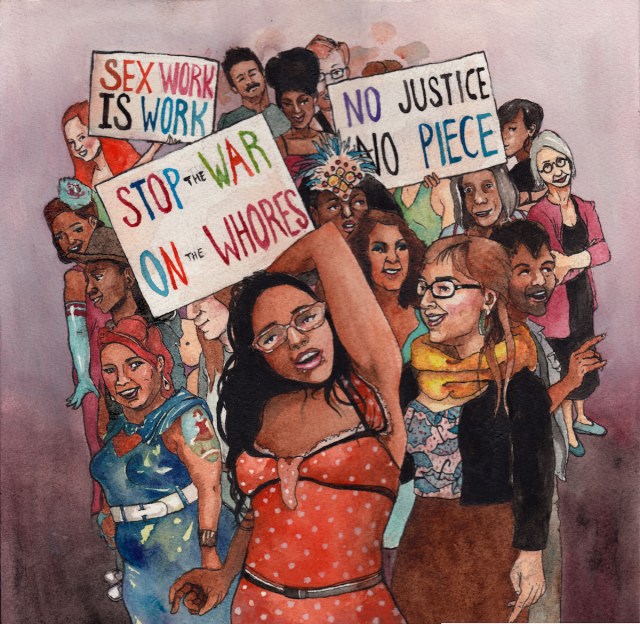

On April 11th, 2018, I opened my Instagram with a heavy heart. My feelings of anxiety and confusion were mirrored back in the posts that filled my feed. FOSTA had just passed and sex workers everywhere were left reeling in the aftermath. With a quick vote and stroke of a pen, one million people found themselves unable to work safely. Over three months have passed and the mood on Instagram has shifted. Although the feelings in the community are still dismal, there is a sense of solidarity. Leading up to the approval of the bill, hundreds of sex workers took to their accounts to urge people to repeal the bill, to call their senators and prevent this legislation from passing. Now that it’s passed the outcry of injustice hasn’t faded, it has evolved. Now flooding my feed are resources and survival tips from one sex worker to another. Sex workers are resilient and face near-constant opposition via social stigma or legal obstacles. Regardless of the conditions, for some people, it is the only way to feed their family. The FOSTA-SESTA package-bill is not going to save sex trafficking victims; it’s just going to turn consensual sex workers into victims themselves. Decriminalization is the only solution to preventing sex trafficking and separating sex workers from that label.

People who aren’t in the industry often label my own job as dangerous and exploitative. I’m a stripper, and in the world of sex work, dancing is considered relatively cushy. I have the privilege of it being (mostly) legal, I have bouncers in the building who can handle unruly customers, and if someone threatens me, there are cameras and people everywhere. In order to stay open and legal, sex acts are heavily discouraged by strip club owners and can result in the termination of dancer contracts. However, for some full-service sex workers, strip clubs are now the only place besides the streets to safely meet clients.

Across the states, laws on nudity vary by jurisdiction. What is legal in one city might land a dancer in jail in another. In the case of Oregon, friction dances with two-way contact are legal, yet in Ohio, that same style of dance could get you slapped with a Lewd Conduct charge (as in Stormy Daniels’ case recently). Some cities allow full-nude air dances while others only allow table dances. These regulations are rarely enforced and hardly publicized making it difficult for strippers to feel secure in the eyes of the law. In addition to creating legal gray areas, this type of “hush-hush” atmosphere makes women vulnerable to police sexual-violence and jail time as a result

In 2006 during an interview with The Inquirer, from inside Pennsylvania State Prison, former Trooper Michael Evans remarked, “If it’s a former stripper or a prostitute, they might think no one will believe them… [M]ost of these people don’t have the highest self-esteem. That’s why they become preyed upon.” I concede that most strippers and full-service sex workers would think twice before reporting an assault to the police, especially if an officer of the law commits that assault. Many women report sexual assault only to have their appeals for justice dismissed. Great deals of these women hold traditionally respectable jobs and still struggle to be believed without the stigma that women in the sex industry have working against them. However, I reject Evans claim that low self-esteem causes these women to experience sexual assault at the hands of officers and others. Instead, women make easy victims for predators due to the social stigma that surrounds their job. It’s common for public officials to make use of the gray haze that surrounds sex work to bolster their moral image.

Just this January, numerous strip clubs in New Orleans were subject to police raids under the guise of “human trafficking” takedowns. Eight clubs had their liquor licenses revoked with the justification that prostitution, drug dealing, and lewd acts were being performed inside. However, no human trafficking arrests were made. Instead of pimps and sex-traffickers, dancers were arrested and charged with everything from performing a lewd act to prostitution.

Critics argue that police are targeting sex workers instead of real sex trafficking victims; they cite the lack of sex trafficking charges that have been filed after the raid. When questioned about the missing sex trafficking charges, ATC Commissioner Juana Marine-Lombard remarked, “Prostitution in and of itself is sex trafficking.” This simplification of such a nuanced subject takes agency away from the women who choose to do full-service sex work. It also undermines and takes the focus off of real sex-trafficking victims. To use the terms “prostitution” and “sex trafficking” interchangeably is not only harmful, but legally incorrect. Melissa Gira Grant, a Senior Reporter at The Appeal, a national criminal justice news outlet, makes note of this difference in her story on the NOLA raids: “[…] prostitution is not trafficking. Trafficking, as it is defined by the state of Louisiana and under federal law, requires force, fraud, and coercion; prostitution does not.” This differentiation is often glossed over by both the mainstream media and government officials.

Yet this legal distinction seems to mean nothing to not only popular media, but members of the House who on February 27, 2018, passed FOSTA-SESTA with a vote of 388-25, or to members of the Senate who on March 21, 2018, passed FOSTA-SESTA with a vote of 97-2. With names like Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act (FOSTA) and Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act (SESTA) these joint-bills seem like a safe way for members of Congress to tout their morality and compassion. However, impact matters more than intent when it comes to saving lives and these bills not only do nothing to actually reduce sex trafficking, but they also create dangerous conditions for both sex trafficking victims and consenting sex workers.

Pre-FOSTA, many sex workers considered the Internet viable a place to communicate with both clients and each other. They were able to use websites like Backpage and Craigslist to post ads and screen clients. After the FOSTA-SESTA bill passed, sex workers couldn’t do much but watch in horror as their places of refuge shut down. Fancy, a full-service sex worker and teacher in academia, outlined the necessity of these websites and the importance of screening clients during a phone interview on April 17th 2018:

We want to make sure that they [clients] have no issues with our boundaries, that they have never been aggressive or violent. That they have never stiffed someone on payment, any kind of acts of aggression we want to weed out as much as possible, and the internet really gave us the freedom to do that, I was an isolated worker for 13 years before discovering online communities and working online, and the difference in safety was incredible, and I’m watching […] all of that disappear now.

It’s important to understand what FOSTA-SESTA actually means legally before beginning to understand its negative impacts on the sex industry. FOSTA-SESTA will retroactively hold social platforms legally and criminally responsible for the content and actions of their users. This means that if a user posts an ad for a sex trafficking victim on Craigslist, not only would the trafficker be prosecuted, but the host of the ad space (Craigslist) would be held liable as well. While this may seem like a reasonable approach to prevent sex trafficking, it actually makes it harder for law enforcement to locate victims and keep tabs on known traffickers. As disarming as it is, without the online advertisements of victims, officers are left without necessary tools to send help.

Lawmakers do a disservice to actual sex trafficking victims when they focus on criminalizing sex workers and their clients. Amnesty International makes note of this on their Q&A page pertaining to the human rights of sex workers, “ …criminalization of sex work can hinder the fight against trafficking – for example, victims may be reluctant to come forward if they fear the police will take action against them for selling sex.” Criminalizing sex work effectively forces both groups of people off the Internet and onto the street, which is a dangerous place to be.

According to Fancy, not only have sex workers followed the progression of FOSTA-SESTA since it was first introduced in the House, but pimps have been as well:

Almost everyone I know who is out as a sex worker and active on Instagram has been getting DM’s from pimps that use fear tactics regarding FOSTA, because the pimps also know, and predators in general, serial killers, rapists, they all know about this law and they are aware of what it does [. . .] Right away when FOSTA became a serious concern [. . .] myself and everyone I know whose out as a full-service sex worker started getting messages from pimps saying ‘oh its not safe on the streets, it’s not safe on the internet, you can’t find clients, how are you gonna eat, come work with me [. . . ] and they rely on the fact that we’re all panicking about FOSTA to try to fool you.

It is questionable whether any of this information matters to those who passed FOSTA-SESTA. With this legislation pushing more sex workers onto the street, the incidences of murder, rape, and assault are inevitably going to rise. It is difficult to directly back up this claim due to a grievous lack of comprehensive data on violence against sex workers — however, if one works backwards, and searches for reduction in violence against women, a recent study conducted by researchers at WVU and Baylor universities finds that when Craigslist introduced the Erotic Services section, violence against women was reduced by 17.4%. Furthermore, the study found that to match this same reduction without the use of an Erotic Services section, 200,832 additional police would have to be employed, amounting to an extra $20 billion per year using higher levels of police employment.

For the vast majority of full-service sex workers, going to the police for help is not an option. Fancy explains the hesitation: “Most full-service sex workers, especially street-level, women or people of color have experienced violence at the hands of the police, and historically, the police do not see sex workers as believable victims and typically they arrest us for being assaulted. They’ll arrest us on a prostitution charge if we report an assault.” Authorities are more interested in arresting consenting adults than actual victims of human trafficking. In fact, while much of the blame for trafficking is placed on the sex industry, over half of sex trafficking victims originate from the foster care system. According to the National Foster Youth Institute, 60% of child sex trafficking victims recovered through FBI raids across the U.S. in 2013 were from foster care or group homes. In a recent analysis of the accounts of 292 survivors of sex trafficking, Polaris Project states, “A significant number of survivors disclosed that their trafficker was a family member. Parents or other relatives in caregiver roles were cited as being controllers, typically when the survivor was a minor.” The Polaris Project breaks this number down with 31.51% of victims being trafficked by a romantic partner, and 9.59% trafficked by a family member. Therefore, a key to preventing trafficking may not be targeting online hosts, but paying closer attention to the federal and local foster care systems.

Aside from the faulty correlation between sex work and trafficking, sex workers are consistently put on the spot when it comes to the subject of exploitation in general. Author Melissa Farley, states in a paper presented at Psychologists for Social Responsibility annual meeting, “Prostitution occurs because the person being sold for sex would not agree to have sex with the buyer unless he paid for it.” She further pushes that money is a means of coercion, and when money is involved, consent is removed. While Farley is correct in her initial statement — after all, it is fair to assume sex workers wouldn’t be interested in sleeping with their clients for free — she neglects to recognize that money is a means of coercion for everyone. Fancy backs up this assertion that often sex workers are held to a different standard than other workers:

How I handle things like that now after many, many years of dealing with it, is just asking people to hold their jobs to the same standard that they hold sex work to and see how that works out. Like do you enthusiastically consent to do your job for free? Then why should sex workers? Do you feel that your boss exploits you? In what way is that exploitation better than the exploitation that may occur with sex work?

The FOSTA-SESTA package-bill does little to address the fact that the majority of sex trafficking victims have roots in the foster care system and instead puts the blame on host sites. Even if the sex industry does play a role in sex trafficking, it is important to understand that consent exists on a spectrum as well as coercion.

The Polaris Project reports, “survivors who reported working for strip clubs and formal escort agencies were more likely to describe their controller as an employer. Some survivors of formal escort agencies disclosed knowing that they would be engaging in commercial sex from the outset of the situation. However, they reported that the nature of the situation was frequently not what they expected, and survivors reported experiencing debt bondage, blackmail, threats, and sexual abuse that prevented them from leaving the situation.” Those last two sentences are important because they highlight the complexity of consent.

Using sex trafficking and prostitution interchangeably normalizes the incidences of sexual assault experienced by sex workers and implies a certain degree of consent to the abuse experienced by sex trafficking victims. After all, many people believe that in a certain way, sex workers are consenting to their abuse. To the public, violence is an unavoidable and expected part of sex work. This implication is repugnant but all too common and prevents both sex workers and sex trafficking victims from seeking police help.

In Prostitution Policy: Revolutionizing Practice Through A Gendered Perspective, Lenore Kuo expresses the harm of normalization and indifference: “Ambivalence is core to violence against women in general, but ‘prostitutes are subject to it in the extreme.” Indeed, these attitudes create an insidious “credibility culture” where a person must be seen as a credible victim by both the public and law enforcement in order to be taken seriously. This phenomenon is illustrated by politicians’ unwillingness to listen to the voices of the marginalized people they supposedly represent. It’s reasonable to believe that to a certain extent, public officials do recognize the difference between sex work and sex trafficking. The various NOLA strip club raids in late 2017 and early 2018 in search of sex trafficking victims that instead resulted in prostitution charges is evidence of this. Ignorance is not to blame for past legal assaults on the rights of sex workers, nor is it to blame for the recent legislation calling for a ban on all hosting sites. Instead, it is morality politics at play that are resulting in the deaths of sex workers across the nation.

As referenced earlier, Craigslist’s’ introduction of the Erotic Services section reduced violence against women by 17.4%, this percentage is based on one single website. That statistic doesn’t take into account the numerous other hosting sites that popped up after, allowing sex workers the ability to screen their clients. The researchers summarize their analysis with the suggestion that the reduction in violence against women was due to sex workers gaining the ability to work indoors instead of street-side, in addition to matching with safer clients via online screening.

It cannot be emphasized enough how important harm reduction techniques are to the safety of sex workers. The ability to work indoors can be the difference between life and death. Fancy maintains that access to online hosting sites and screening tools made a profound difference to her personal safety.

We want to make sure that they [clients] have no issues with our boundaries, that they have never been aggressive or violent. That they have never stiffed someone on payment, any kind of acts of aggression we want to weed out as much as possible and the Internet really gave us the freedom to do that. I was an isolated worker for 13 years before discovering online communities and working online, and the difference in safety was incredible, and I’m watching all of that disappear now.

This puritanical agenda is stripping sex workers of their ability to practice online harm-reduction techniques and is forcing both victim and sex worker to disappear into offline shadows.

One underreported issue is that of racial disparity within the sex industry. Sex workers of color are more likely to be targeted by law enforcement than their white counterparts. According to a 17-year-long study examining arrest data from three heavily populated cities in North Carolina, “Law enforcement’s focus on outdoor prostitution appears to result in black females being arrested for prostitution at higher rates than their white counterparts and at rates disproportionate to their presence in online advertisements for indoor prostitution”. Unfortunately marginalized groups, more often than not, serve as the “canary in a coal mine” when it comes to human rights violations.

Until sex work is decriminalized victims of sex trafficking will be vulnerable to not only their traffickers but to the persecution of their peers and local law-enforcement. Marginalized individuals within both groups will be forced to operate in the shadows and if discovered, subjected to the scrutiny of law enforcement. It is time to examine whether policymakers are truly devoted to ending sex trafficking. The voices of sex workers may be easy to ignore, but the statistics in favor of online screening tools are glaring. Meanwhile, as long as Congress and the electorate play respectability politics and deny sexual agency, sex workers will continue to die.

Comments

I appreciate the detail and nuance in this article – it’s one of the most thorough critiques of FOSTA-SESTA I’ve read. I definitely learned a lot, and I’m glad AS is publishing reporting like this.

Thank you for your feedback! Honestly, the scope of sex work focused laws is so expansive, it’s wild. These laws definitely have a ripple effect and impact so many people, including non-sex workers as well. Thanks again, for your kind words.

Same; I was familiar with the outlines of FOSTA-SESTA but learned a lot reading this (and I’ve added “Prostitution Policy” to my to-read list). I joined A+ to help support pieces like this.

Thank you for your support! I’m really grateful to Autostraddle for accepting my article for publication and I’m very thankful to Fancy for giving me some of her time and emotional labor to talk about FOSTA-SESTA. I learned a lot during the process of writing this, so I’m happy to know that others took something from this too.

Thanks for writing this! It’s clear and personal and actionable. I’m so angry that sex workers’ lives are being made more vulnerable through this

Thank you for your comment! Sometimes I worry about “droning on and on” so I’m glad you found it readable.

Thank you for taking the time to write this. I definitely learned a lot and now have something to reference when talking about this issue with other folks. You also provided a book for further reading, so I hope my library has a copy.

I’m also curious as to how this affects sex workers in Nevada, where sex work is legal.