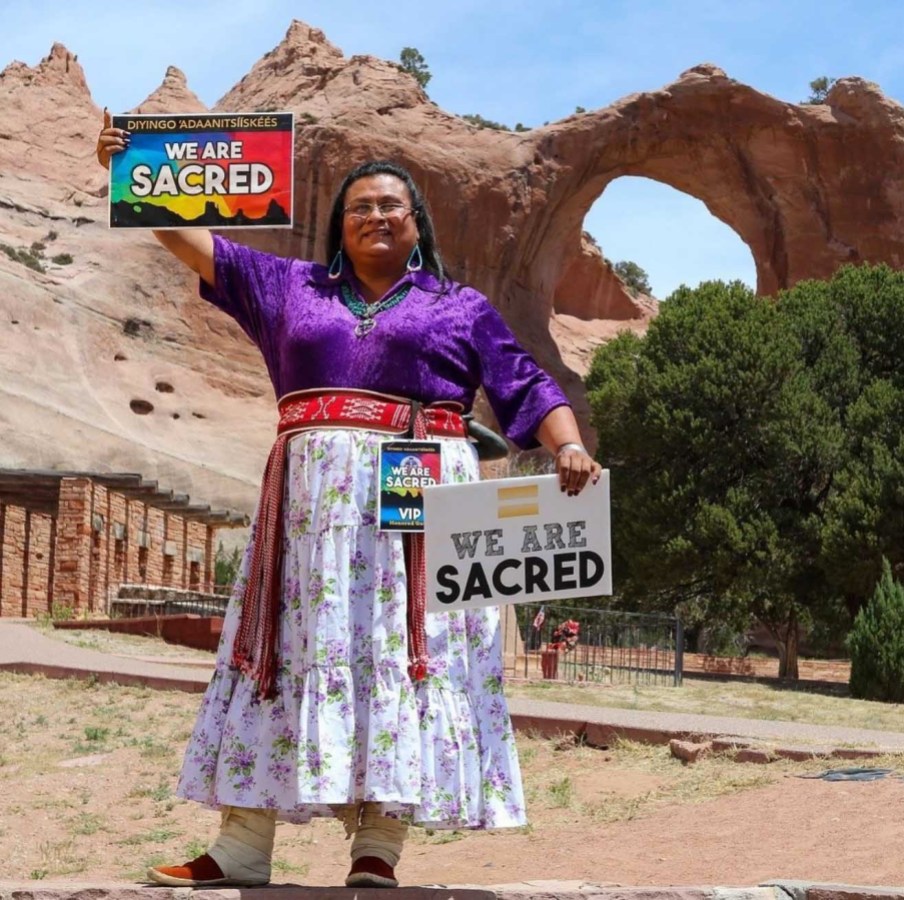

A month of convergence: the pandemic, ongoing uprisings to defend Black lives, Native American Heritage Month, Trans Day of Remembrance, and a presidential election. After what felt like a year of waiting to exhale, Mattee Jim celebrated the loss of President Trump with a symphony of honks and rejoicing voices. “I was cruising up and down for four hours. I didn’t even mind going slow,” she said. Many were dancing in the streets. She placed her trans flag on her dashboard so it could be on full display: as a Navajo trans woman, many parts of her were relieved.

Mattee Jim is of the Zuni People Clan and born for the Towering House People Clan. This is how she identifies as a Diné — the word that those in the Navajo nation use among themselves. She’s speaking to me from her office at First Nations Community Healthsource, where she’s returned, despite the pandemic, to ensure her Native communities have the resources for HIV prevention. She’s been doing this work for several decades.

She was born in Gallup, New Mexico, which lies near the arbitrary border that cuts through the Navajo nation, a line meant to indicate when New Mexico becomes Arizona. Navajo voters like Mattee were instrumental in flipping Arizona, a battleground state, blue. Yet, in many exit polls depicting voter statistics by race, Indigenous voters were forgotten, placed into the “something else” category.

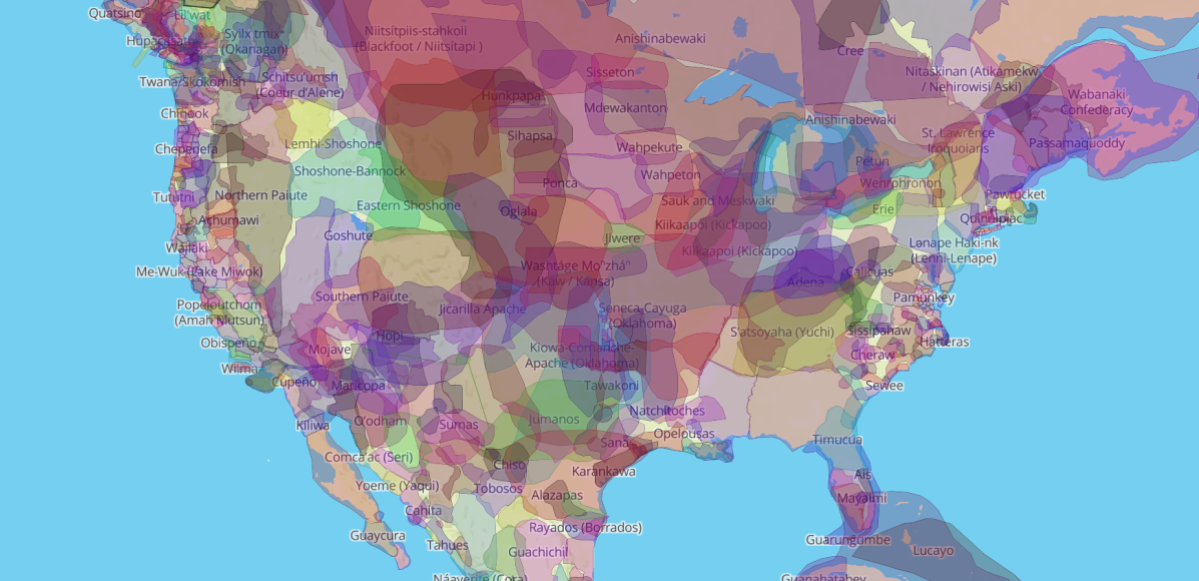

Despite the Native words that are scattered across a map of the U.S. — Milwaukee, Oklahoma, Malibu, Tallahassee, Mississippi River, and Yellowstone National Park are just a few — the meanings of these words have been warped, assigned new values by colonizers. Few youth today are taught that both the American constitution and the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848, the first feminist convention in the U.S., were inspired by the laws and matrilineal traditions of the Haudenosaunee people. Indigenous knowledge has been the well of inspiration that colonizers have drunk from, only to poison the water later on.

A map of precolonial nations and tribes provided by native-land.ca.

Mattee was one of the Native youth whose life was shaped by the American neglect of Indigenous populations. Her decision to become sober at the age of 24 was the turning point. Three years later, she began identifying as trans, after she started working with the Coalition for Equality in New Mexico in the late 1990s, an organization that works towards a “reality of equity, full access, and sustainable wellness for LGBTQ New Mexicans.” Prior to that, she had never even heard the word “transgender.”

While Stephanie Byers of the Chickasaw nation has made history this year as the first Native trans person to be elected to office in America, Native trans youth rarely have the stability to become politically engaged. “Getting into politics wasn’t our priority,” Mattee explained. “How to get to the hospital, how to go to the grocery store, how to get transportation, our livelihood was first and foremost.” Due to high rates of homelessness, food insecurity, and unemployment, many Native LGBTQ people cannot afford to get involved in politics.

Over the last few years, Native issues have reached greater visibility, especially after the fight against the Dakota Access Pipeline began in 2016. Columbus Day in many cities has been renamed Indigenous People’s Day. Meetings and rallies, particularly among community organizers, begin with an acknowledgment of the original stewards of the land.

That work took decades of pressure from marginalized communities. After centuries of erasure, evident in the loss of languages, Native culture is still being preserved by protectors like Mattee. Despite the dual layers of invisibility being both Navajo and transgender, Mattee proudly proclaims her sacred role in community spaces she enters. While trans issues have become a national discussion only recently, gender-variant people from Indigenous communities have been historically accepted and revered for their contributions to society.

Diyingo ‘Adaanitsíískéés (We Are Sacred)

“From what I’ve learned growing up, the elders would tell us that we’re special people,” Mattee recalled. “A family was blessed to have someone in their family who was LGBTQ. The riches were the knowledge they knew, the roles they played, the tasks they do.”

Trans people in Indigenous communities, across the world, added to the abundance of knowledge about the human soul. As with the Navajo nation, trans people in Vietnam, called chuyển giới, were traditionally mediums who helped people speak to their ancestors. In India, the gender-variant community of hijras were revered as having the ability to bless or curse marriages through fertility rituals. Among the Zapotec people of Oaxaca, transfeminine muxes are often artisans and craftspeople. The city even celebrates gender diversity in a three-day festival called Vela de las Intrepidas. In Hawai’i, the māhū were people who could embody both masculine and feminine spirits, and they were traditional healers, caretakers, and teachers. Since the beginning of the fight for Mauna Kea, a sacred mountain threatened with destruction through the construction of a telescope, māhū leaders have been among those at the forefront of the battle.

From left: Vogue Mexico features muxe communities for the first time. The Kinnar Akhada community of India prepares to dip, in ritual, in the Ganga. Hinaleimoana Wong-Kalu, māhū leader and teacher, raises her fists in ceremony.

Through her advocacy work, Mattee educates on Native trans identity and has been viewed by her friends to exhibit cultural roles and characteristics of historical Native trans individuals such as Osh-Tisch. The name, which means “finds them and kills them,” refers to the two-spirit person from the Crow nation that earned her moniker through her fierceness in battle in the late 1800s. Osh-Tisch later was imprisoned by an American federal agent, who forced her to cut her hair, wear masculine clothing, and perform manual labor. The Crow nation stood by Osh-Tisch and found a way to remove the federal agent from their land. Chief Pretty Eagle called their treatment of her “unnatural” — a word often used today to disparage trans people rather than, in this case, the abuse of trans people. Since the time of Osh-Tisch’s life, the perils set up by colonizers have continued to plague Native trans people.

Mattee explains that for Native trans women, there are two overlapping phenomena: the ongoing genocide of Native people and the attack on trans bodies. The two are demonstrated through community-led initiatives meant to track the disappearance of these communities, one being Trans Day of Remembrance and the other being Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, and Two-Spirit People (commonly shortened to MMIWG2S). In the face of heightened danger, many Native trans communities end up tracking their own community’s survival, not being able to rely on the government or media. “We have Native trans women who’ve been murdered in the State and in our tribal communities…I’ve had conversations with other Native trans women. Within our Native communities, we know where the girls are. If someone was missing, we’d know.”

Her work has been bridging the worlds of trans justice and Native sovereignty. Speaking at the United States Conference on HIV/AIDS last year, she asked a crucial question: “A lot of Native communities, especially trans communities… at a lot of the meetings, trainings, and national tables, we’re not included whatsoever. How many of you are including Native populations in the work that you do?”

Her demand for inclusion isn’t simply about weaving Native people into advocacy spaces. Mattee embodies the world that colonizers have tried time and again to eliminate. She is the manifestation of the trans wisdom her ancestors had celebrated. Each time she commands respect, she invites us onto the bridge with her: the bridge between binary genders, the bridge between trans and Indigenous movements, and the bridge between our past and the future. She invites us into that world where we’re allowed to be our whole selves without limitations, whether we know it or not. It’s our job to accept the invitation by giving her and every ancestor before her what they’re due. It’s our duty to remember.

Thank you for this reporting.

I loved this, thank you Xoài. I loved the meaning you imbued into the idea of remembrance.

And yeah that whole “something else” statistic name was…something else.

Thank you

Thank you for spotlighting all the wonderful work done by native organizers in Navajo Nation! 🎉

This is so good and necessary, thank you.