January is Makeout Month at Autostraddle.com

Before I started researching the subject, I thought the history of the kiss-in — a protest tactic used sporadically by LGBTQ+ organizers throughout the second half of the 20th century and throughout the last 20 years — would be straightforward. As is the case with most of the protest strategies organizers have employed, I believed the narrative of its inception would be fairly basic: A group comes up with an idea for a demonstration, and they put it into action. What I found as I dug into archival material, news clippings, books on LGBTQ+ history, and reports about more recent kiss-in protests is that kiss-ins seem to have been sparked by entirely organic circumstances, but none of the resources I consulted are entirely sure. The oldest reference I can find to an event close to what we would think of as the modern kiss-in happened in the middle of another demonstration without much forethought or planning. Organizers and participants took to the streets for an arranged march, and, on their own, began kissing each other en masse. It’s hard to say whether this initial kiss-in was simply a declaration of their love for each other and enthusiasm for being there or was a way to push onlookers to witness a completely normal act of affection among people who were tired of being shoved out of the public eye. Either way, this very first act of spontaneity grew into a form of resistance employed in the fight for queer and trans rights for nearly 50 years.

An ‘Act Up’ march on Fifth Avenue, on the 25th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots, New York City, USA, 26th June 1994. (Photo by Barbara Alper/Getty Images)

According to the earliest reports, the first documented kiss-ins happened in New York City in 1970, but there’s not enough evidence to figure out which kiss-in occurred first. In some reports, the first recognized act of kissing as protest took place during the gay liberation march organized by the Eastern Regional Conference of Homophile Organizations and other NYC-based gay activist groups to commemorate the first anniversary of the Stonewall Riots in Greenwich Village on June 28, 1970. It’s reported that thousands of people showed up for the demonstration, which marched from Greenwich Village to Central Park before ending in a “gay-in” which included appearances from leaders of gay liberation groups around the country and opportunities for protesters to meet and socialize with each other. During the march, shirtless activists kissed each other and held hands openly in front of onlookers.

Separately, in Marc Stein’s book Rethinking the Gay and Lesbian Movement, the author writes “…in 1970, gay liberationists staged a ‘kiss-in’ at a New York bar that had ejected two men for kissing…” and documents that, in Los Angeles in 1971, a group of lesbian activists staged a kiss-in at a restaurant that threatened to expel two female patrons who were holding hands, but doesn’t provide any additional detail beyond that. Meanwhile, as the early 1970s rolled on, Gay Liberation Front (GLF) activists in London organized the UK’s first Gay Pride Parade in Trafalgar Square on July 1, 1972. The UK GLF activists planned a mass kiss-in as a feature at the end of their march through London, which is said to have drawn over 2,000 participants. Then, in 1973, a Los Angeles lesbian activist coalition, the Lesbian Feminists, organized the First National Lesbian Kiss-In at the Los Angeles County Museum of Arts in protest to the lack of inclusion of female artists in the museum’s exhibitions and collections. And in 1976, gay organizations in Toronto staged a kiss-in at the intersection of Yonge and Bloor Streets to protest the arrest of two gay men who were taken into custody for kissing each other at the intersection.

Members of the Lesbian and Gay community stage a Valentine ‘s Day “Kiss-In” 14 February 1988 outside St Patrick’s Cathedral in New York to present a message of their unity and love in the face of the “church condoning anti-gay and anti-lesbian violence”. (Photo by MARIA BASTONE / AFP) (Photo by MARIA BASTONE/AFP via Getty Images)

From there, the kiss-in recedes into the background as far as an organizing strategy goes. But like much of the history of marginalized people, I wouldn’t ever put it out of the realm of possibility that they were being organized and executed or happening as part of larger LGBTQ+ demonstrations occurring throughout the 1970s. The latter half of the 1970s saw the birth of Anita Bryant’s “Save Our Children” campaign in 1977, a “movement” that claimed gay and lesbian people were just pedophiles-in-waiting and successfully pushed lawmakers in Miami, Florida to repeal the equal rights ordinances passed in the county’s legislation. A year later, in 1978, the state legislatures of both Oklahoma and Arkansas passed state laws barring gay and lesbian teachers from teaching in the states’ public schools. Similarly, California’s Proposition 6 — commonly referred to as the “Briggs Initiative” — sought to do the same thing but was ultimately voted down by California residents and was never passed.

When we’re considering the impact of this kind of legislation by lawmakers, people have a tendency to forget that along with the bills themselves comes an onslaught of campaign propaganda from their proponents. Bryant’s “Save Our Children” campaign alone featured not only the high profile representation of its founder and her constant appearance in the media, but organizers in various cities also passed out brochures, spoke to local residents, and got into the ears of state and municipal lawmakers. Despite the unrelenting anti-gay atmosphere of the time, LGBTQ+ activists never backed down from these fights. However, it seems entirely possible that as these tensions continued to mount further and more severely throughout the end of the 1970s, it became more dangerous to stage kiss-ins and/or openly document the kiss-ins that were happening as verifiable proof such as a photographs or eye-witness accounts threatened to dismantle the lives of LGBTQ+ people.

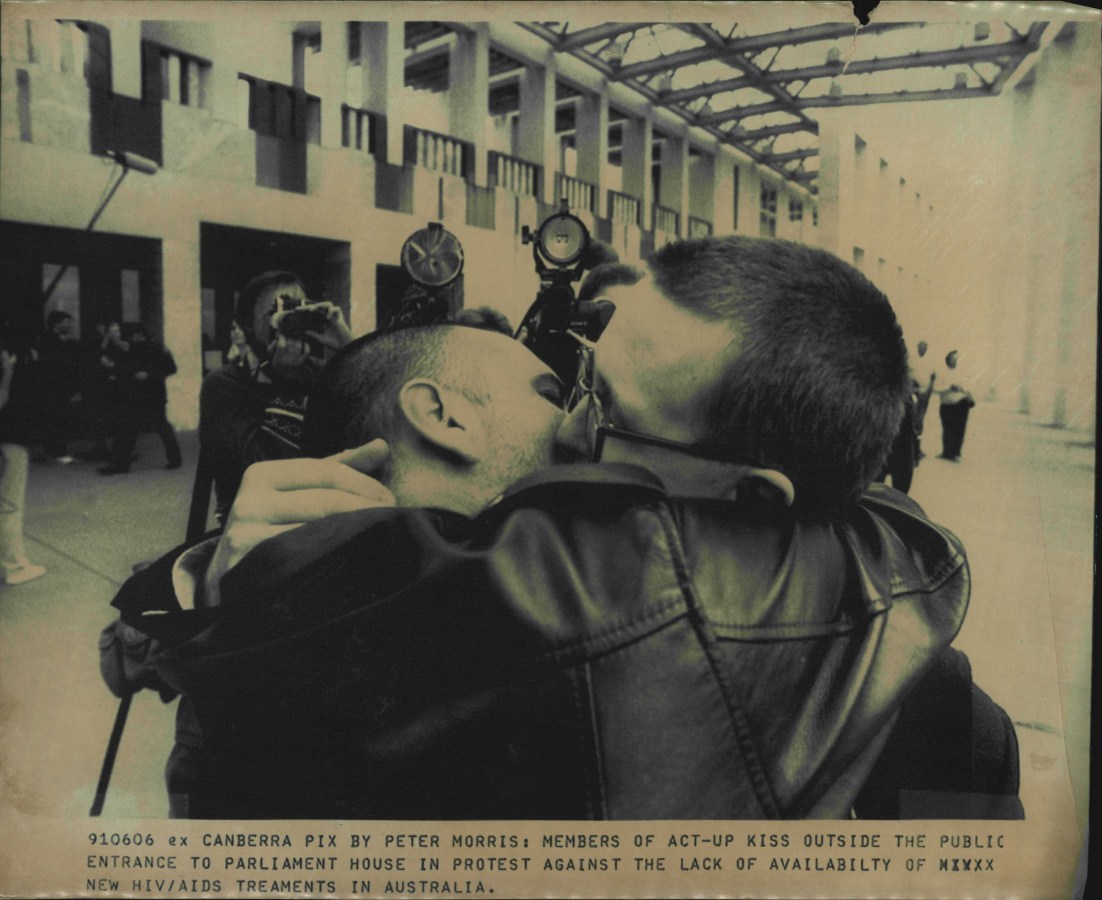

Members of Act Up kiss outside the public entrance to parliament house in protest against the lack of availability of new HIV/AIDS treatments in Australia. June 6, 1991. (Photo by Peter Morris/Fairfax Media via Getty Images).

Although “Save Our Children” didn’t work everywhere, the anti-gay attitudes bred by these “movements” rode straight to the end of the decade. Then, in 1981, LGBTQ+ activists were given yet another reason to fight against state and federal powers as the beginning of the HIV/AIDS epidemic ignited anti-gay tensions in a new way and would soon lead to a lack of medical intervention on the part of what many dubbed a “gay disease.” It’s through these circumstances that the kiss-in comes hurtling back as a feature of queer activism and becomes more significant than ever. ACT UP — the grassroots organizing group dedicated to fighting for the funding of HIV/AIDS treatment among other radical initiatives like instituting nationalized healthcare in the U.S. — was founded just before the height of the epidemic in 1987. By 1988, the group was already holding kiss-in protests as an act of rebellion against both the increased severity of homophobia in the U.S. and against the stigma about the transmission of the disease from HIV-positive people. The first ACT UP Kiss-In was executed on April 29th, 1988 as part of ACT UP’s ACT NOW National Spring AIDS Actions (also known as “The Nine Days of Rain”) that took place from then until May 7th across 50 different cities. According to the archive of film artist and writer Jim Hubbard, the New York City Christopher Street Kiss-In on that day drew the participation of over 1,000 protesters who showed up to kiss each other in Sheridan Square at the end of the Christopher Street march.

That same year, a group of 11 visual artists and graphic designers dubbed Gran Fury emerged from ACT UP. Gran Fury quickly became ACT UP’s “unofficial propaganda ministry” and began creating a series of agitprop artworks and campaigns aligned with what ACT UP was fighting for and against. In 1989, Gran Fury developed a public art project called “Art Against AIDS on the Road” — the group’s first “high stakes” opportunity to publicize and distribute the work ACT UP was doing — that included the now legendary “Kissing Doesn’t Kill: Greed and Indifference Do” poster and postcard-mailing campaign featuring three mixed-race couples kissing. Loring McAlpin, an artist who was part of Gran Fury, noted that “Within a year or so, our poster was on buses and subway platforms in San Francisco, Chicago, New York, and Washington, DC.”

HOUSTON- August 18: 1992 Republican National Convention Protests. Queer Nation and ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) activists by the political action of kissing in public, protest the Republican Party, anti-gay policies of the Catholic Church, anti-gay policies of the U.S. military, and the American government’s negligence in the AIDS crisis at the Mickey Leland Federal Office Building on August 18, 1992 in Houston, Texas. (Photo by Lindsay Brice/Getty Images)

From there, kiss-ins and kissing in general became an essential part of ACT UP’s organizational tactics and culture. As Jack Lowery writes, “Kissing was an integral part of ACT UP’s culture, beyond just ACT UP’s kiss-ins […] If you saw a friend at an ACT UP meeting, you greeted them with a kiss. It was the same if you met up with an ACT UP friend for drinks or coffee. [Heidi] Dorow described kissing as a blood pact. ‘Everyone in the world tells me to be afraid of you, and that you’re a danger,’ was how she described its rationale. Kissing someone refuted this. It was a way of saying, ‘I’m not afraid of you. I’m with you.’”

Throughout what was left of 1989 and through the early 1990s, ACT UP chapters across the U.S. and Canada continued to stage kiss-ins when they felt it was strategically relevant and tactically significant — such as their historic protest against anti-queer discrimination at Manhattan’s St. Vincent’s Hospital and their protest at the Female Health Company urging the federal Food and Drug Administration to allow the marketing of the Reality Female Condom for anal use.

As ACT UP continued to take the streets in protest of the way the HIV/AIDS epidemic was being handled and to stand up for LGBTQ+ impacted by the disease, kiss-ins were also used by LGBTQ+ college campus organizers in the early 1990s. In 1991, the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender Ally Alliance (LGBTAA) and the co-founders of the campus’s Phi Alpha Gamma fraternity held a kiss-in on the ISU campus. The LGBTAA press release for the event stated, “We have made a conscious choice to refuse to live by the implied standards of our society. Where our cultural ‘norms’ refuse to recognize same-sex affection, we refuse to accept those restrictions.” Although the event was highly controversial at the time, the initial ISU kiss-in evolved into a yearly event that took place until its final iteration in 2009. On the East coast, Queer Nation Ithaca, a group formed of members from other LGBT organizations at Cornell University and the local community, organized a Valentine’s Day kiss-in protest against heterosexism and homophobia in 1992. That evening, Queer Nation Ithaca “staged a rally in the center of The Commons, a pedestrian shopping mall located in the heart of Ithaca’s commercial district. A substantial audience was guaranteed, as many Ithacans were likely at The Commons to celebrate the holiday.”

Denise Penn, left in foreground, an advocacy journalist for lesbian news, of San Clemente, kisses Jean Harris, field director for Dean For America (Governor candidate Howard Dean), Saturday during a kiss-in at Orange County’s first Dyke March at Lions Park in Costa Mesa. The parade aimed to promote social change, celebrate women and fight discrimination, anti-gay violence and harassment. The event, which began at Lions Park, included live entertainment and women’s health information. The march was sponsored by the Gay and Lesbian Community Center. (Photo by Al Schaben/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images)

The organizing focus of the mainstream LGBTQ+ community began to shift in the mid- and late-1990s and early 2000s and kiss-ins, once again, seem to disappear from the toolbox of activists working for LGBTQ+ rights because documentation of these events seems to stall. We can posit a number of reasons for why that might be — the fact that some significant rights gains were made, the push for queer assimilation and the adoption of more heterosexual cultural values, etc. — but there’s not a lot to prove for certain that they continued or stopped happening all together. Nonetheless, the kiss-in has experienced a bit of resurgence over the last 15 years and has even been co-opted by non-queer people, especially internationally. 2014 and 2016, for example, saw the organization of kiss-in protests organized by mixed student groups in Santiago, Chile and Kerala, India, respectively. The Santiago “Kiss Party” protests were organized as part of a larger university student response to the government’s lack of public funding for education in the country. India’s “Kiss of Love” protests were at least somewhat reminiscent of those early queer kiss-ins in that they were organized to protest the conservative policies regarding morality policing installed in the country by Narendra Modi and the right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party.

A little earlier, in 2007, the Italian LGBTQ+ organization Arcigay held a kiss-in following the arrest and temporary detention of two gay men who shared a kiss at the Colosseum (which is especially ironic considering the storied gay history of the Roman Empire). The kiss-in and the subsequent trials of the men who were arrested actually led to the creation of Rome’s “Gay Street,” a temporary protest zone in the middle of the city where LGBTQ+ people were allowed to party and protest freely. Responding to the potential passing of a rash of laws that would make “gay propaganda” illegal in Russia in June 2013, Elena Kostyuchenko and other LGBTQ+ activists staged a series of protests in front of the Russian State Duma, including one dubbed “Kissing Day.”

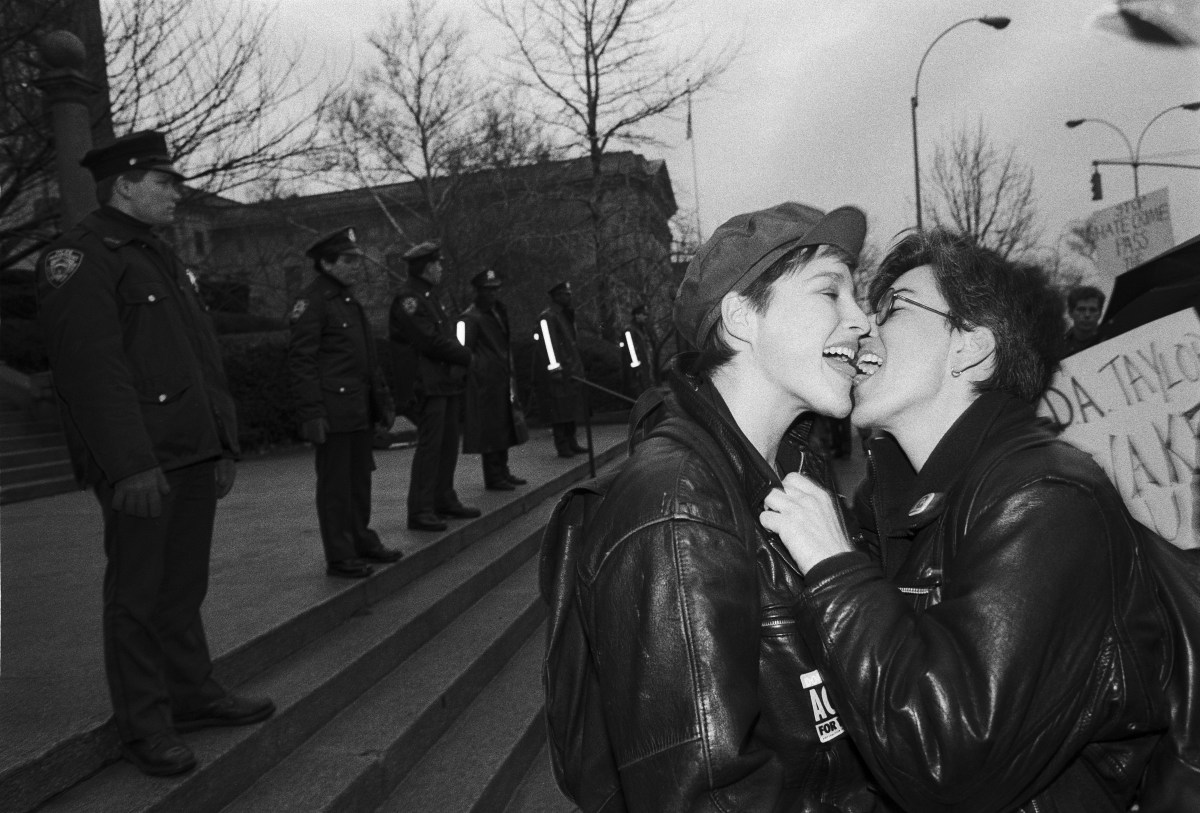

Two Women kissing in front of a line of police officers during a gay rights demonstration in Staten Island in New York in 1990. (Photo by Thomas McGovern/Getty Images.

In the U.S. and in the UK, on the other hand, kiss-ins were utilized to protest corporations that had exhibited discriminatory practices against LGBTQ+ people. Although these are much less notable and consequential to me as the more radical kiss-ins staged by ACT UP organizers and others earlier in our history, they were still somewhat successful in terms of participation. At the height of the 2012 Chik-Fil-A anti-same-sex-marriage controversy, gay rights activists organized a “kiss day” at Chik-Fil-A locations across the U.S. The organizers created the event in response to the fast food chain’s president’s opposition to same-sex marriage and did manage to draw both participants in various parts of the U.S. and thousands of notes of support on different social media websites. Similarly, gay rights activists in London staged a massive kiss-in called the Big Gay Kiss-In on August 8th, 2016 at the Hackney location of the supermarket chain Sainsbury’s. This kiss-in was staged in response to a high-profile act of anti-gay discrimination by a Hackney Sainsbury’s security guard who told a same-sex couple to leave the store because they were holding hands. According to the media and the organizers of the event, an unexpected 200 people showed up for the event. The most recent time LGBTQ+ activists in the U.S. utilized a mass kiss-in was on Valentine’s Day in 2018. That protest — organized by Voices 4 and the NYC-based RUSA LGBT, a non-profit group that supports LGBTQ+ immigrants, asylum seekers, refugees, and allies in the United States who came from Ukraine, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Russia, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Armenia, and other Eurasian countries — was organized to call attention to the eruption of violence against LGBTQ+ people happening in Azerbaijan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan.

Since the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic are still ongoing, the 2018 queer kiss-in will likely be the last one we see in the U.S. for some time, but the kiss-in’s place in the history of nonviolent activism in the U.S. shouldn’t be so obscured and difficult to access. I’ve written before about my doubts in the efficacy of nonviolent protest tactics, and I don’t feel differently about kiss-ins. At the same time, though, I can imagine these moments were incredibly empowering for the people who organized and participated in them at the times they occurred. As it’s become clearer and clearer that the most powerful individuals and groups are again attempting to force queer and trans people back into the closet and out of the watchful eye of mainstream society, I think the lesson provided through these examples is helpful for us as we continue to organize against the subjugation of queer and trans people. When these kiss-ins were held, they were considered radical and menacing to the societies that experienced them. We can use this example to help lead us into figuring out new ways to organize that are more intimidating and have an even larger material impact on our future together.