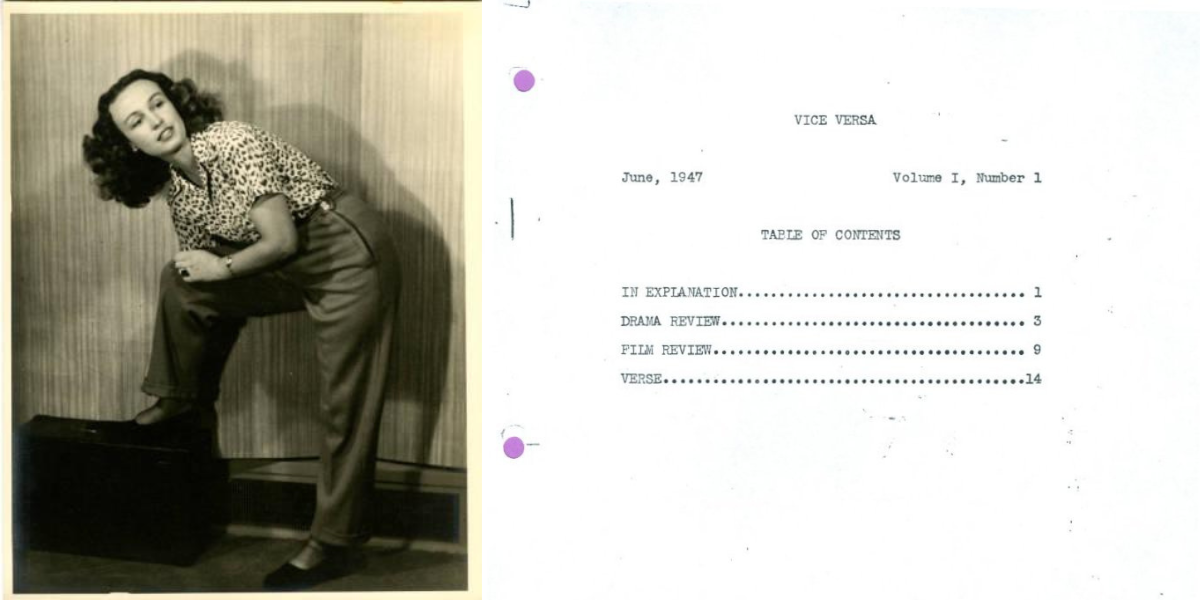

In 1947, Edythe Eyde, writing under the pseudonym “Lisa Ben,” launched the country’s first-ever lesbian magazine, Vice Versa. Her boss at RKO Pictures in Burbank wanted her to look busy even when she had no work to do, so she’d use her office’s manual typewriter to write the magazine and carbon paper to print 12 issues of each issue, which she distributed for free, imploring readers to pass it on to another lesbian when they finished. The goal of Vice Versa was to provide information and visibility, but Ben also really hoped it’d be a way for her to connect with other gay girls.

Vice Versa shuttered when Edythe got a different job at which she lacked private access to a typewriter and carbon paper, but her passion for writing began before Vice Versa and continued after it. She continued to write sci-fi/fantasy (she was an early and active member of the Los Angeles Science Fiction Society), poetry (including a series devoted to her 22 cats), and gay-themed (but “not dirty or demeaning to us”) parodies of popular songs, which she performed at gay clubs in Los Angeles throughout the 50s. She published as “Lisa Ben” in the Daughters of Bilitis’ seminal lesbian publication The Ladder and hung out on the fringes of the nascent lesbian activist movement, but she never considered herself an activist. After a relationship in her thirties ended with her girlfriend losing all their money through gambling, she swore off serious relationships for life.

Edythe eventually retired and hunkered down with her cats in the Burbank bungalow she’d bought in 1960. In the 1970s, in true lesbian cat lady fashion, she fought the city of Burbank’s attempt to get her to give up all but three of her 32 cats and won.

Throughout the 80s, she was frequently interviewed by various historians and writers for anthologies and documentaries. By the 90s, she had “gone into seclusion,” and much of her personal correspondence during this time are copies of refusals to attend events she’d been invited to.

And then, at the turn of the century, heading into her eighties, Edythe Eyde found a new focus that had nothing to do with lesbian media or visibility: her local Hometown Buffet.

Buffets came to America via Sweden, who brought a smorgasbord to the 1939 World’s Fair inside the Three Crows Restaurant, inspiring a few buffet-style restaurants to crop up in the 50s. America’s first All-You-Can-Eat Buffet was launched in, of course, Las Vegas, at El Rancho, one of the Strip’s first hotels. After becoming all the rage in Vegas, buffet restaurants spread across the country, peaking in the 1980s. Chains like Sizzler, Golden Corral, and Ponderosa were especially popular in the suburbs, where they targeted big families looking for a cheap meal that’d please all involved parties.

Buffets Inc. was founded in 1983, with its founders splitting in 1986 to start their own chains which included, in 1989, the Hometown Buffet. In 1996, Hometown re-merged with Buffets Inc, a company that would come to own Ryan’s Buffet, Old Country Buffet, HomeTown Buffets and Country Buffet — thus creating the country’s 25th-largest restaurant chain, with combined sales of $661 million in 1996.

These restaurants were abundant throughout the 1990s, writes Eater, who describes them as “a value proposition: why pay for one plate of food when, for a few extra dollars, the restaurant will serve up an unlimited amount of food?” Buffets have always been most beloved by children and senior citizens. Every year on Valentine’s Day, Hometown Buffet sweetens the deal with free lunch and a portrait photo to couples who’ve been together 50 years or more.

As a kid, I loved buffets — at Ponderosa, at hotels, and eventually the new Old Country Buffet that moved in to the strip mall out by the highway. Creamy artificial macaroni and cheese, Jell-O salad, bowls of fried shrimp and cafeteria-chopped spaghetti, iceberg lettuce drenched in ranch, anemic slices of greasy pizza, slivers of cheesecake. I could eat all of these things I never ate at home, all at once, on the very same plate, if I wanted to.

Buffets, like much of hospitality history, is a pet interest of mine, so when an archivist at the One Archives at the University of Southern California told me that in retirement, Edythe had become a superfan of her local Hometown Buffet, I was drawn by forces larger than myself to spend a few ays in the archives, reading everything I could from the Lisa Ben Papers. And indeed, nobody loved buffets like Edythe loved her local Hometown Buffet.

Edythe loved writing letters on her typewriter to her friends around the country, and they are long and detailed and misanthropic and delightful.

Prior to the opening of the Hometown Buffet, Edythe’s letters to her friends detailed issues including the ordeal of closing one’s MasterCard account, finding a good pair of shoes at Mervyn’s, the high price of movies, the low price of artichokes at Trader Joe’s, the priceless pleasure of reading entire books at Barnes & Noble (but not eating the soup there, which she had on good authority arrived frozen), the new practice of Baskin-Robbins employees putting out tip jars, the extensive trials and triumphs of her numerous “pussy-cats” and feral cat rescues, the extensive trials and triumphs of various kitchen appliances, and her affection or lack thereof for the many restaurants within a safe driving distance from her home. (She didn’t like driving too far, as it meant being away from her cats.) On Wednesday mornings, she went to the American Thrift Shop to look for shirts with cats on them. Her home-cooked meals, as described in her letters, were budget-friendly affairs: marked down meat with Lipton’s noodles and sauce, or Wilson Fully Cooked Roasts.

In December of 2001, Edythe wrote to her friend Kay Kidd — they’d met through a cat newsletter — about a new shopping center opening in Burbank that would contain a Hometown Buffet. “To my delight, a Hometown Buffet has sprung up,” she typed. However, she lamented its inadequacies compared to a former Burbank buffet, Furr’s (specifically, Hometown lacked Furrs’ carved meat selection, and did not allow patrons to seat themselves) and derided “the waitress’ ploy to coax tips” by serving beverages she was perfectly capable of obtaining herself.

That sentiment would soon take a significant turn. By February of 2002, Edythe reported that Hometown “has improved its food choice since I first visited there” and that she’d taken to eating lunch there every day. “Today they offered Chinese chicken livers,” she recalled. “Yesterday, among many selections, was Cheese Enchiladas. I tucked away three of them! Oink-oink.”

Edythe learned of Hometown’s opening via a television advertisement, featuring “a little child running to its mama with an overloaded dessert plate, with an array of food in the background.”

She was disappointed that the ad didn’t reveal the restaurant’s location. (Two years prior, she’d written to her local TV station to complain that their Applebee’s ad also played coy with the restaurant’s address, requesting they reconsider this tactic so she could visit what appeared to be a very good restaurant.), but also felt strongly that what Hometown really needed was a jingle. “It’s time for one of these eating places to use a catchy tune in their ads,” she wrote. “None of them do and the competition is fierce here in Burbank.”

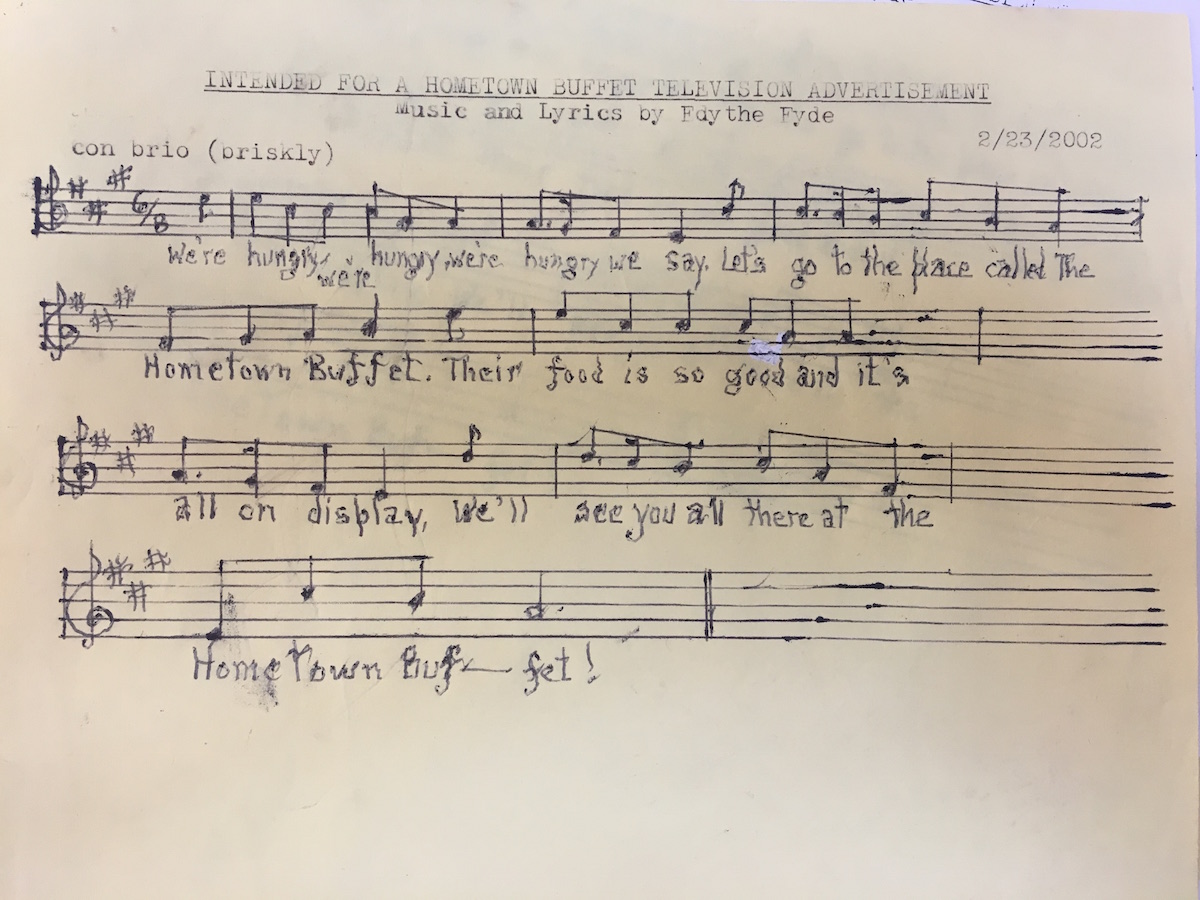

She’d been writing songs for decades, so it’s no surprise that the Buffet Advertising Muse struck her on one of her daily drives to Hometown, gifting her with a melody and words, an experience she described as “good gracious, it was tenacious!”

We’re Hungry, We’re hungry, we’re hungry we say!

Let’s go to that place called The Hometown Buffet,

Their food is so good and it’s all on display,

We’ll see you all there at the Hometown buffet.

“I think children watching TV will pick up on the tune and will be signing ‘We’re Hungry, We’re Hungry,’ which will automatically remind parents, and everybody else, of The Hometown Buffet,” she wrote to Kay.

That day at lunch, she’d introduced herself to the manager and secured the address of the company head in charge of their TV advertising. “If I just send it to the agency,” she explained, “Someone there will take credit for MY music and lyrics. After all, it was MY dream and I deserve the recognition!”

She wrote a long letter to the company, enclosing sheet music, lyrics and a short treatment for the television ad, pointing out how none of her local restaurants were using music in their TV ads, and a compelling jingle could worm its way into the minds of children.

Debbie Tucker, the senior Director of Marketing for Buffets, Inc, rejected Edythe’s submission on the following grounds:

First, we have just finished shooting our television commercials for the year 2002. We won’t produce any new spots until 2003. In addition, our advertising agencies’ policy is to always create commercials that are based on concepts developed through the year by the creative, research and strategic departments of the agency, as opposed to being based on individual non-strategic ideas. Our advertising agency also has a policy of using music in our TV and radio commercials that is composed and performed by union talent only.

After this rejection, Edythe decided to stop eating at HomeTown, instead choosing to patronize El Pollo Loco, Honey-Baked Ham and Boston Market. She had “one last meal” at the restaurant and left the manager, Tom Neuzil, a stack of her cat poems for his wife, a vet.

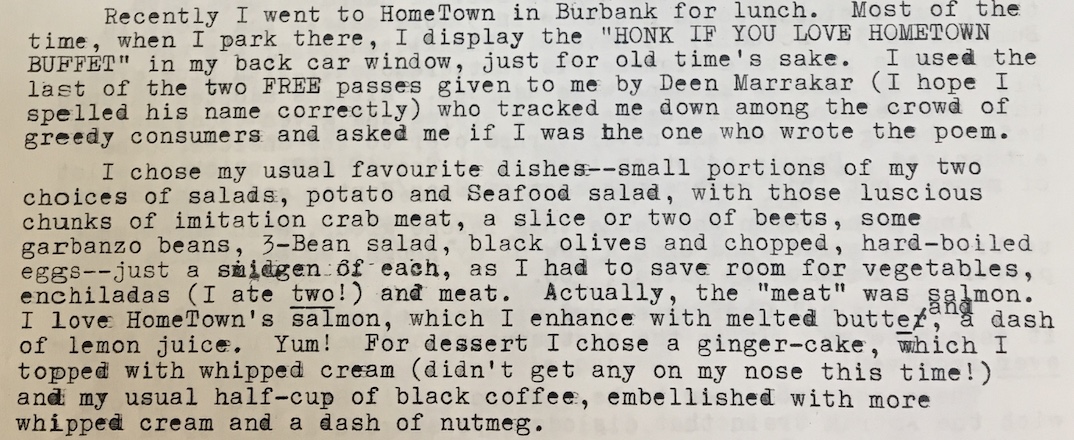

By 2003, however, Edythe was back at Hometown Buffet, and her relationship with Neuzil apparently grew deeper, as revealed through extensive correspondences between the two from 2004 through 2008, as well as brief correspondences with other managers and employees of the Burbank Hometown Buffet. She often referenced time they spent together in the store drinking coffee with nutmeg. Edythe and Neuzil kept in touch even after he was transferred to a Ventura County store, while he was hospitalized, and while he was living in Illinois to be closer to his family.

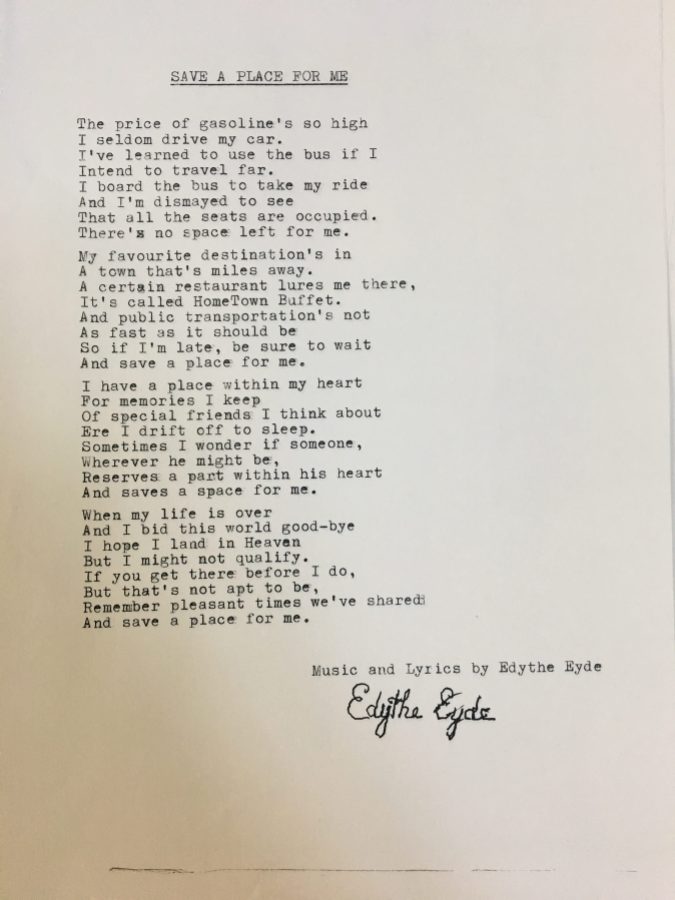

She wrote him long letters about her life and shared stories of her evangelicalism for Hometown Buffet, like the “Honk If You Love Hometown Buffet” sign and Hometown Buffet t-shirt she’d printed for herself. Her local store rewarded her with gift cards and a pin. She published a poem in their corporate newsletter, but the poem was full of errors, which in true editorial spirit, she wrote them a letter detailing. (Sample correction: “The chicken liver should have an S on it (as I originally wrote it) to go with the verb “are.” One can’t just say chicken liver ‘are’!”)

Neuzil sent Edythe framed photographs of herself and the Hometown staff from her trips to Hometown Buffet, musical Christmas cards, a “Cute Kittens” stationary set. She sent him seeds for his garden and recordings of herself performing the Hometown Buffet jingle. She informed him of the inadequacies of her local store’s coupon strategies, detailed her bus trips to Hometown Buffet (she’d decided against the hassle of renewing her driver’s license), and of course as always, talked about her cats.

Edythe Eyde in her “i Love Hometown Buffet” t-shirt

Edythe seemingly struggled with depression and isolation throughout her life, although she never names it. Long letters from her early twenties detail fights with her parents, shame over living with a man who cheated on her, her loss of faith in God, and her desire to end it all. Her early fascination with and connection to written media is clear, even then: She submitted a question about her parents’ financial demands and her father’s temper to the advice column of a local newspaper and saw it published. She was proud of her self-sufficiency, her job and that she bought her car in cash — but often lamented that something sadder still tugged at her.

Although later communications indicate a change of heart about her affiliation with the lesbian community, in a letter to Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon from the 1960s she declares she had no interest in attending the Daughters of Bilitis conference as she’d lost her passion for “that way of life” after a hospitalization two years prior and her disastrous three-year relationship. She wrote that she’d become convinced she would “never find the security and stability I crave so much in the half-world I used to champion so wholeheartedly.”

Undated letters from the ensuing years indicate periods of time when she’d lost interest in everything besides “eating, certain television programs and in sleeping.” She had health issues, felt tired and listless, and was distressed by the concept of making herself presentable enough to go out.

In 1987, she attended an Old Lesbians Organizing for Change convention in Carson, which she complained left her “depressed for days” afterwards, having been regaled by stories of women with bowel incompetence and losing their partners. But in 1988, she was recorded for The Daughters of Bilitis Video Project, cheerfully speaking about her early gay life, Vice Versa, and performing her songs.

Edythe comes alive when she’s discussing the topics she’s most passionate about: her music, her writing, her cats, and her Hometown Buffet.

Letter from Edith to Tom Neuzil

When Edythe started her “little gay magazine” in the 1950s, she didn’t have an agenda. She didn’t want to be famous or turn her magazine into a proper, professional publication. She didn’t even know she was the first lesbian to start a magazine, or that it would be illegal to send it through the mail, and she certainly had no idea that her name would be written in the annals of lesbian history forever. She simply loved to write: poems, jingles, reviews, long personal stories. She wanted people to know, just as we do now, if there was a movie or a book with something gay in it. She loved getting letters and writing letters, hearing about someone’s life and sharing the intricate details of her own. Her happiest correspondences are those in which a friend has expressed enthusiasm or excitement for a song or poem she shared with them.

In 2002, she told queer historian JD Doyle reaching out about her work that she’d gone into seclusion: No, I have not gone over to the other side, but I no longer actively participate in the gay lifestyle. To do so at this stage of my life would be inappropriate. But when the same historian reached out in 2003 for information on another musician, she wrote three pages of joyful memories of her life in Los Angeles lesbian scene in the 1950s and enclosed some of her song parodies for him to enjoy.

“It was just some writing that I wanted to do to get it off my chest and I was a very lonely person and I could sort of fantasize this way by writing the magazine, you see,” she told historian Eric Marcus about Vice Versa in an interview later used for his podcast, Making Gay History. She wrote an author who wanted to reprint Vice Versa pieces in a gay anthology that she was amazed people were still interested in her “little endeavors of so long ago” when “there are so many gay-oriented magazines, newspapers, plays, etc., now that surpass my humble ‘publication,’ which actually was never printed, but typed on an ordinary typewriter!”

Edythe Eyde wrote to connect, to feel a part of something larger. In the last years of her life, in her correspondence with the management of Hometown Buffet and her affection for the employees who recognized her on her visits, it’s all there, too: a desire to connect, to see how much more we have in common than we have at odds, to keep in touch, to let people in. Certainly, nobody associated with Hometown Buffet knew that Edythe once created a lesbian magazine. She was just a friendly retired woman with a bunch of cats. It’s silly, because Hometown Buffet is a terrible restaurant. But it’s also so undeniably human, and so sweet. It’s all there in those letters, just like it was back then, too.

The last bit of correspondence available from Edythe to her Hometown Buffet friends is dated December 2008, and the entirety of her paper records (donated to the One Archives by her neighbor in November 2014) conclude in 2009.

In 2010, she was inducted into the National Lesbian and Gay Journalists Association’s Hall of Fame.

In 2015, she passed away in an assisted living facility.

In 2020, The Burbank Hometown Buffet, along with all remaining stores in the floundering chain, shuttered permanently.

Courtesy of the ONE Archives

What a lovely article about an interesting person. May we all find something we love as much as Edythe loved Hometown Buffet.

“May we all find something we love as much as Edythe loved Hometown Buffet.”

Couldn’t agree more!!!

Under her other pseudonym – Tigrina – she was also involved in the science fiction scene of 1940s Los Angeles:

https://fiawol.org.uk//FanStuff/THEN%20Archive/LASFS/Tigrina.htm

Thank you!!

i used to go to the Hometown Buffet with my parents on Staten Island when i was a kid in the 90s. in the fall of 2007, i too used to frequent the Burbank Hometown Buffet with my friend while we did a semester at our college’s LA campus. i wonder if i ever ran into Edythe, or at least saw her in passing. what a fascinating woman!

iconic that you’ve been to THE hometown buffet in burbank, i would like to exist in the world believing that you did indeed see her there

Did you ever go to that Hometown Buffet or did you found about her love for it after the Burbank locale closed. My parents took us to Hometown Buffet once in the late 90s or early 00s. It wasn’t the Burbank one, which was closer, but I think we went to the one in southern Ventura near the county line.