I recently heard CeCe McDonald speak, and the youngest person in the room stood to ask a question. This small human was probably nine or ten, and asked CeCe what other transgender women she looked up to. CeCe named Janet Mock and Marsha P. Johnson, among others, and the moment elicited a collective awwwww from the several hundred people in the room. I thought about how important it is for young humans to learn about the leaders in our multi-faceted struggle for justice.

On the 45th anniversary of Stonewall and the 50th anniversary of the Civil Rights Act, it’s worth interrogating how we learn and know our histories. For many of us, our time in school is foundational in how we see the world and ourselves. In school we have histories and literature delivered to us, and whether or not we saw ourselves in those histories or books impacts us. But along with the concrete material presented to us, we also inevitably absorb how we are treated by our teachers, peers and other school staff. School is a social experience. It’s where we learn where we fit — or don’t.

Stonewall! via TransAdvocate

There have been various calls in recent years for LGBTQ representation in our textbooks. A 2009 study by GLSEN suggested that including LGBTQ people and history in classrooms helps make schools safer places for LGBTQ kids. This type of curricular inclusion validates young LGBTQ people’s identities and promotes our history as important and significant to the current state of things. But just putting some events — Stonewall, the overturning of Prop 8, etc. — in our books is far from enough. To keep it so simple would make it too easy to write the history of LGBTQ struggle as on its home stretch toward a finish line of marriage equality and workplace nondiscrimination laws for all, when there is still so much left to be done on the front of mass incarceration, police brutality, homelessness, unemployment, poverty, discrimination and violence that queer and trans people face every day. In order to include a history that is both relevant and empowering for LGBQ and T populations, textbooks need to accurately represent our history and the struggles that remain. For example, effective and inclusive historical representations of Stonewall would talk about the role that trans women played in the riots, and would discuss how trans women were later pushed out of the Gay Liberation Front so the cis people in the organization could be more easily accepted by a mainstream American population.

That being said, it’s important to acknowledge that it’s not like American history curriculums are doing a wonderful and comprehensive analysis of other marginalized groups’ histories and has just unfortunately left out LGBTQ people. There are so many ways that social movements and histories of struggle have been poorly represented in American schools that teach a white-dominant, male-dominant, heteronormative and imperialist narrative of American history. If you took American history — and if you even got to the Civil Rights Movement after the long chronological slog through a detailed history of every war the U.S. ever fought — it’s likely you learned about Rosa Parks as a lady who wanted to rest her feet while taking the bus home from work, so she sat down in an open seat in a spot reserved for white people, was arrested, and then suddenly there was a yearlong bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama. What you probably didn’t learn is that Parks was an activist who had been organizing to fight sexual violence against black women for many years prior to the riots, and that it was largely because of the community networks created by anti-sexual violence organizers that the bus boycotts could be so successful.

This nearly-forgotten history (which you can read about in Danielle McGuire’s very excellent book, At the Dark End of the Street) gives insight into the intersections between women’s struggle and the struggle for civil rights. It also challenges white-dominant narratives of feminism that have white women inventing the fight against sexual violence, and male-dominant narratives of the Civil Rights Movement that relegate women to insignificant roles.

The way the entire Civil Rights Movement is depicted in U.S. history books shows a tendency to package struggle into a neat narrative that allows the Civil Rights Movement to be depicted as a relic of the past, rather than one that continues to be relevant today, as the Supreme Court hands down decisions that would infringe mostly on the rights of women of color, and black and brown bodies continue to be criminalized and marginalized. History books don’t have to ask for a continuing interrogation of injustice in American society if they depoliticize the politics of past struggles. Another significant example of how struggle and violence are written out of mainstream American narrative is all the talk of “Manifest Destiny” in US history textbooks. Traditional lessons on Manifest Destiny mask its history of genocide and colonization of native peoples by portraying it as a harmless great America-expander.

If it sounds like these kinds of lessons would take a lot of time — they would. And we could talk about the shortcomings of American history textbooks probably forever, but another factor in limiting the kind of things kids learn about in school is the state of education in the US. We are not exactly at an easy moment in American education to be creating a more elaborative and critical curriculum. The push by corporate entities and administrators for education reform has been heavily opposed by teachers and students, but is, nonetheless, happening. These reforms, like the implementation of the national Common Core Standards, put increased emphasis on high stakes testing, both in measuring student achievement and teachers’ performance, which means more instructional time has been dedicated to test prep and test-taking, pretty much across the board.

Kathy Kremins, who has spent 33 years as a public high school educator, noted some of her concerns with Common Core: “[Common Core] maximizes ‘informational texts’ and minimizes poetry… ignores graphic works and YA literature; it strongly advises against creative analysis and activities.” And most teachers don’t have the 33 years’ experience Kremins has. Increased pressure and workloads on teachers as a result of the emphasis on test scores and other reforms imposed by administrators has led to poor working conditions for teachers and incredibly high teacher turnover, which means that teachers don’t have time to refine their skills and tailor their curriculum to address their students’ needs.

via Labor Notes

Public school teachers who have tried to include history and perspectives of historically marginalized groups, including LGBTQ perspectives, have been suppressed, despite all signs that indicated their positive impact on the grades and lives of their students. The Ethnic Studies programs in Tucson, Arizona were targeted by the city school board and then made illegal by state law; and more recently on the college level we saw South Carolina create their bizarre penalty system for universities who taught LGBTQ curricula.

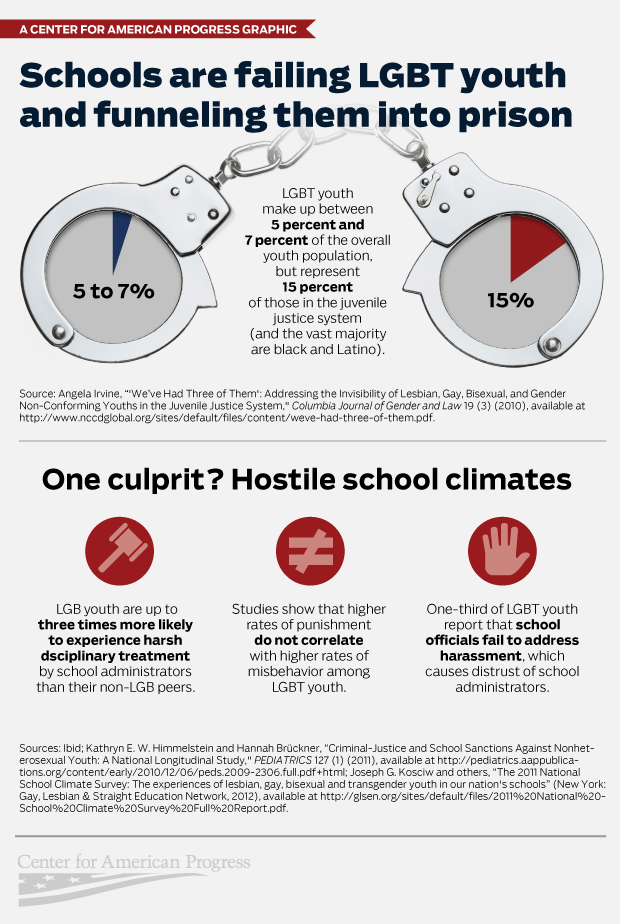

Also, it doesn’t matter much what’s in the curriculum if students are being criminalized in the classroom. The growth of the school-to-prison pipeline has disproportionately targeted black and Latin@ LGBTQ students. Validation or safety that could be nurtured by the inclusion of LGBTQ narratives in a curriculum can’t cancel out the negative impact of fear and antagonism created by a heavily policed environment on a student’s ability to learn and thrive.

We can hope for a world where the young people who don’t get to talk to CeCe McDonald in person will learn her name, and the names of other people who inspired her and other people who have struggled for justice, but ultimately a lot more needs to happen across the entire educational system for ALL kids to have safe, inclusive and empowering experiences in school. The impact of high-stakes testing, the school-to-prison pipeline, pressure on teachers and other shifts in the educational system impact our community and youth in ways that we will continue to feel far into the future.

So much good here. I’ve been thinking for a long time how important it is that LGBTQ kids learn our history. I see the same mistakes being made, ignorance about the price people paid for the relative gains we’ve made, and so much more that a more honest, well-rounded education would change. And let’s face it, the US doesn’t deal well with our history of race at all–Rosa Parks’ “moment of defiance” is a particular sticking point. (I like Ronald Takaki’s A Different Mirror for the non-white history of the US.)

I wish I learned more about gender in middle school and high school, instead of the misinformation(and fetish material) I got doing a search on yahoo. It would have really helped me out in my early 20’s instead of feeling a bit old and hopeless to transition. Maybe I could become a civics teacher in HS(thought about it when I was at Uni), but then I am not sure how cool California is with teaching students some of the stuff you mentioned here.

Representation in textbooks is extremely important but I think it will be one of the things we have to wait longest for. I’ve edited coursebook series and I know that many publishers won’t consider featuring a pig in a textbook, for example, because they want to sell the rights globally and illustrations are expensive. Sad but true that showing a queer human being would be even more taboo than a pig in some countries but there you go. I used to tweak the art briefs to have the dad washing up while the mother sits at the table reading the Financial Times, but that was as far as I got.

Teachers can/should mediate between the textbook and class though. For example, when I was teaching ESL kids I mentioned that a girl could have a boyfriend or a girlfriend, so you shouldn’t ask only ‘do you have a boyfriend?’ The next kid up went for “Do you have a looooooover?’ Which wasn’t what I expected in the slightest.

My school doesn’t have textbooks, exactly – at least, not those giant, 400+ page conservative, bland retellings of American/world history that I had in school. Instead, we do “unit books,” where someone (I) collects all of the related materials from the library collection and delivers them to the classrooms.

I try to make those selections as diverse as possible within the limitations of the library collection, and I’m trying to diversify our fiction and nonfiction collections. There’s some good LGBT fiction for kids (King & King, My Mixed-Up Berry Blue Summer, etc), but I haven’t had much (any) luck finding LGBT nonfiction for elementary schoolers. I couldn’t find any biographies or even histories of LGBT movements.

Now, getting my boss to buy them is another problem entirely, but I can’t even propose these titles if they don’t exist/I can’t find them. If anyone has suggestions (pre-K through fifth grade), I’d love to hear them – and I figure y’all straddlers would know.

So many great options!

Try:

-And Tango Makes Three

-My Princess Boy

-Antonio’s Card (haven’t actually read this one but it’s bilingual AND about a kid with two moms!)

-The Family Book, by Todd Parr (only a quick mention of families with 2 moms/dads, but it’s for pre-K to K, which is great)

-Anything by Jacqueline Woodson (her YA stuff has more queer representation than her picture books but the picture books do show lots of different types of families – foster care, one parent in prison, etc. and she is a queer author so that’s cool!)

The Teaching for Change Bookstore has some great suggestions:

http://bbpbooks.teachingforchange.org/best-recommended/lgbtq

Good luck!

We have fiction (Tango Makes Three, In Our Mothers’ House, and I’ve ordered a bunch more that will hopefully be OK’d by admin).

What I really need is nonfiction. We have a couple of books that mention LGBT (usually just LG, unfortunately…) families, but I’m looking especially for biographies of LGBT+ people, who are famous either for their activism (queer or otherwise) or for doing other stuff while queer.

I am currently a queer member of the mentioned American school system and I appreciate this very much. My thoughts translates to Eloquent Adult Speak. Thank you for writing.

As someone who has just finished the AP US history course taught at my school, I agree with a lot of what’s written here. Our textbook mentioned Stonewall in about 1-2 sentences (no one in my class had heard of it before), and had no other information on LGBTQ history. This is a problem, even in the liberal community I live in.

However, I would disagree on some points. My class really did stress non-white history, especially African-American and Native American history. While I would definitely say that the author’s points are true for middle school history courses, I think the College Board does a good job in making sure the AP class at least is diverse and thorough in its teaching.

I’m stuck in what at least people locally refer to as one of the most concentratedly conservative areas of either the midwest or the country, and I didn’t even know what the Stonewall riots were until I came out and started getting really into queer culture, history.

And AP is noticeably better than CommonCore.

I’m lucky in that I live in a liberal town, and yet I still can’t believe the number of homophobic slurs I hear. I can’t imagine living somewhere so conservative.

The first mention of anything remotely nonheteronormative, for me, was in my AP Lit class this past year, my junior year. I go to a charter school that focuses on politics, but even in our lessons, I didn’t hear anything about LGBTQ rights. This year, with everything that’s happened with Prop 8, DOMA, everything, it was never brought up by teachers. Of course, when it came for the speeches unit, people picked social issues, and I had to sit uncomfortably (as really the only “probably gay” person in my class) through multiple homophobic speeches and discussions. And I made sure to bring it up in my AP Comparative Gov class when we talked about Nigeria and Russia, especially (my conservative Christian teacher was not really super into discussing it compared to the Nigerian oil troubles).

My Lit class talked about sexuality a lot (both of the heteronormative and nonheteronormative varieties), though, and it was refreshing to hear my super awesome feminist teacher bring it up herself, and lead students to bring it up, too. When we read Mrs. Dalloway, it felt really good to read things that resonated with me personally. Even if I didn’t feel like vocalizing exactly how they resonated with me.

Science textbooks also need some diversification in the content, and the science behind sexual orientation should be taught to avoid things like the law passed in Uganda with the excuse that “there is no scientific basis for homosexuality”.

Good news today. WHO finally realized that there is no scientific basis for all the crap we have to hear about being sick. I just hope WHO representatives don’t have as president the same kind of moroon as the UN assembly does right now, or this will be water under the bridge. They still have to vote for the diseases to be removed from the book of diagnosis.

http://news.sciencemag.org/brain-behavior/2014/07/no-scientific-basis-gay-specific-mental-disorders-who-panel-concludes

This is a great article and I’m glad it exists.

If I had a zillion dollars like a certain self-appointed education expert, I’d use my money and power to challenge the white heteronormative curriculum used in schools. But don’t worry I would include real teachers and experts in the process.