all photos contributed by the Gerber/Hart Library and Archives

A giant, fabric tongue that once hung in a Chicago gay bar in the 70s and 80s. A magazine created by a group of trans women in rural Pennsylvania. A pamphlet from a lesbian Latina collective in Miami discussing everything from sex to music to spirituality. A collection of photographs of nuns in a convent in Germany. A vial of menstrual blood, given by a partner.

These are just a few of the items given to LGBTQ+ libraries and archives, alongside decades’ worth of photographs, writings, posters, artworks, cherished personal correspondences and more documenting the multitudes of queer life. As legislatures and hate groups seek to censor and erase queer and trans lives and experiences, these spaces, be they physical or digital, housed in universities or grassroots-led, are perhaps more important than ever.

“In my wildest dreams, I would want to have LGBTQ+ history incorporated into mainstream education, and have that be the norm,” says Paola Sierra, Digital Asset Manager at the Stonewall National Museum and Archives in Florida. “I know that when I started at Stonewall, last June, I knew very little. I learned from volunteers talking, just hearing stories. I learned from the archive. I learned from just exposure, and there’s still so much that I have to learn. But it just showed me how absent LGBTQ history is in mainstream context.“

In addition to providing community programming and access to queer texts, these archives create opportunities for LGBTQ+ people to engage with our past, present, ourselves and each other, and can serve as a roadmap for the challenges ahead. They challenge the popular right-wing assertion that queer and trans identity are somehow new, and remind us we have always been here, and always will be.

“Our role as queer librarians, queer educators, queer archivists, is to make sure this information is kept not just safely, but also in a way that people and young people especially can access it, because a lot of these histories are not found as widely as you’d want them,” says Whit Sadusky, an archivist at the Gerber/Hart Library and Archives. There’s historical precedent for the urgency of preserving this history and culture — Sadusky says these histories have been erased before, such as the burning of sex and gender research in Nazi Germany.

Queer archiving efforts are nothing new — and they’ve always faced obstacles. In 1972, the Gay Academic Union, who advocated for the inclusion of gay topics in course content, held their first conference, which went on despite being interrupted by a bomb threat. One of the members of the GAU, Joan Nestle, would go on to help found the Lesbian Herstory Archives in New York, originally housing the collection in her Upper West Side apartment. Today, the intergenerational space provides a transformative experience for visitors from all over the world.

“People send us the hair they cut off when they first came out, the shoes that someone wore for 10 years being a marshal at the Dyke March, all the little things you don’t think are going to matter,” says Lesbian Herstory Archives coordinator Maxine Wolfe. “We had a woman who came once with this little book, it was a replica of something, but when she picked it up, she saw it was from Colombia, which is where she’s from. And she just started crying. People do this all the time. People come and don’t expect their life to be there and their life is there.”

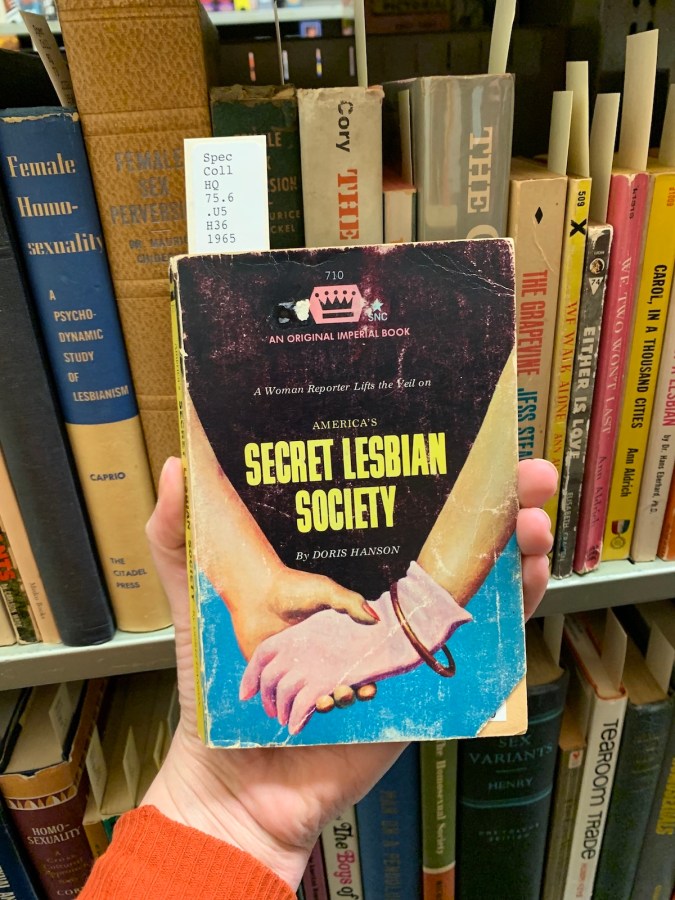

A lesbian pulp novel from the Gerber/Hart special collections

One important function of queer and trans archive efforts is to tell the full, nuanced stories of LGBTQ+ history, aspects of even well-known stories that may be erased, making space for joy as well as rage. One such multifaceted effort is the Toronto-based LGBTQ History Digital Collaboratory’s Pussy Palace Oral History Project, which tells the story of the titular sex party and bathhouse event for queer women and trans people, also the site of the last known police raid on a queer bathhouse space in Canadian history. Collaboratory Research Manager Alisha Stranges says the ongoing immersive multimedia project, for which the team interviewed dozens of former patrons, is about restoring the queer joy, sense memory and sense of place to the historical record about the Pussy Palace, and giving something back to the narrators as well as those who would benefit from access to the archive.

“The Pussy Palace has been documented, but it’s all focused on the police raid,” Stranges says. “There was 10+ years of history of pleasure there. We’re amplifying what we learned about the police raid, but it’s like 20-30%, and the rest has been about bringing forth a more nuanced experience, what people loved about their experience there.”

There is political utility in the collection and dissemination of queer stories, and the team at the Collaboratory say they hope the histories become “raw material for people in the present to create new futures.”

“There are a lot of people who really like ScotiaBank with a rainbow flag in June, and I think by getting in touch with these radical and not-so-radical pasts, we get a little bit closer to what our liberation really means and looks like,” says Elio Colavito, who served as Co-Oral Historian and Research Assistant on the Pussy Palace Oral History Project. “And as this new crisis is brewing, especially around trans livelihood in the States, [but also] certainly in Canada and elsewhere, if we can get back in touch with some of those [histories], we might have an answer for some problem-solving down the line.”

Loni Shibuyama, archivist and librarian at the ONE Archives in Los Angeles, says LGBTQ+ archives can illuminate the historic parallels between the current moment and anti-gay movements throughout the 20th century, most notably the emphasis on “save our children” rhetoric that was popular in the 1970s. “When you work in an archive, you see these anti-gay movements and you see the ways the LGBT movement have fought back, through protest, through advocacy work, through political, economic, artistic means,” she says. “It’s documenting how that struggle is from all different sides, all different ways.”

For Krü Maekdo, who founded the Black Lesbian Archives, a digital and traveling archival project after struggling to find information about Black lesbian history online, queer archives can be an important tool for self-discovery. “When you don’t have a semblance of where you’ve been, it’s hard to presently connect to who you are,” she says. “Those physical and digital archives and oral stories that we tell each other bring us and bridge us together. Some of those experiences that our elders might have gone through, you can relate to those stories, even if they’re not your exact origin story.”

Materials from a pop up exhibit for Black History Month that the Gerber/Hart Archive did at the Center on Halsted in Chicago

Although many of the best known physical LGBTQ+ libraries and archives exist in larger metro areas like New York, Los Angeles and Chicago, they also exist everywhere, a reminder that we exist everywhere, too. Robin Gow, Associate Director of Community Programs at the Bradbury-Sullivan LGBT Community Center in Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley, which houses an LGBT library and an LGBT Community Archive in partnership with Mulhlenberg College, says the archive documents up to 150 years of LGBTQ+ life in the region. Some of the collection has national touchstones, like people from the area who attended Stonewall-era uprisings, but there was a homophile society in the Lehigh Valley even pre-Stonewall doing advocacy and community building. They say having a space for local people to have a connection to their local communities is essential — the study of history in this country has been so gatekept that people may not realize there’s queer history everywhere.

Gow grew up in Kutztown, Pennsylvania, outside of the Lehigh Valley. Kutztown is also the hometown of iconic queer artist Keith Haring, whose work can still be seen around town, although Gow says the town doesn’t really claim Haring’s queerness. Gow didn’t know Haring was gay until he graduated. “I didn’t have a lot of people to look up to, and knowing that people who come from your communities are queer and successful and creative and contributing is really valuable, and I think that it’s purposeful that those parts of themselves are kept from us,” ze says.

Loni Shibuyama says some of the material she finds the most meaningful isn’t from activists, but from people who documented their day-to-day lives with their partners and chosen families. “I get inspired by seeing those photo albums and those letters, those gay bar flyers and materials that show people building community at a time where it was more dangerous to be out than it is now,” Shibuyama says. “When I see photo albums from the ‘50s and ‘60s of people hanging out with their friends or their partners, I get very inspired by people who were just finding their way and finding their own sexuality and a way to connect with other people.”

Yvonne Zipter and Toni Armstrong Jr photographed in 2019 in front of a poster of themselves from the 1980s with the other founders of HOT WIRE – The Journal of Women’s Music and Culture. From the Gerber/Hart Archives 2019 exhibit “Lavender Women & Killer Dykes: Lesbians, Feminism, and Community in Chicago.”

Seeing the everyday joys of queer and trans people that came before can be life-affirming. One of Gow’s favorite pieces in the Bradbury-Sullivan archive is Panzee Press, a magazine created by a collective of trans women in rural Pennsylvania, where writers share coming out stories and other slice-of-life experiences. “I think the political organizing, documents and stuff are great, but I really like seeing when people are building community and doing silly things,” they say. “That’s a part of being alive that feels necessary.”

One of Sadusky’s favorite pieces in the Gerber/Hart collections also speaks to queer joy — the giant tongue from Carol’s Speakeasy, a bar and drag venue from the ‘70s and ‘80s. When the library first received it, it was so heavily caked in cigarette smoke and ash that the team had to clean it with a toothbrush. “Whenever I walk past, I think of all the work that’s been done throughout the generations, specifically by trans women, to make these spaces that queers end up inhabiting safe and happy and joyful and full of art and interest and that’s what I think of now when I look at that tongue, and it brings me a lot of joy,” they say.

Volunteer Curators at 2018 exhibit “The City that Werqs” about the history of drag in Chicago

Compiling and preserving queer stories and histories are one thing, but stewards of these archives are also challenged with making them accessible and presenting them to those who may need them. The Collaboratory team has experimented with Instagram stories, audiograms, and video clips to tell an immersive, sensory story of the Pussy Palace, and is working to spread this to TikTok. They’re also in the process of curating a digital exhibit, where people can enter a website and even visit the Pussy Palace as virtual patrons, traverse nine interior locations, and click on different items in the room to hear stories compiled from the oral histories, compiled from 36 “narrators”—event organizers, bathhouse security volunteers and service providers, patrons, journalists, scholars, and community activists. “I thought we were making this for the general public, but then we demoed this for the narrators and they just seemed so moved and touched by it, that anyone would care this much to preserve their history,” Stranges says.

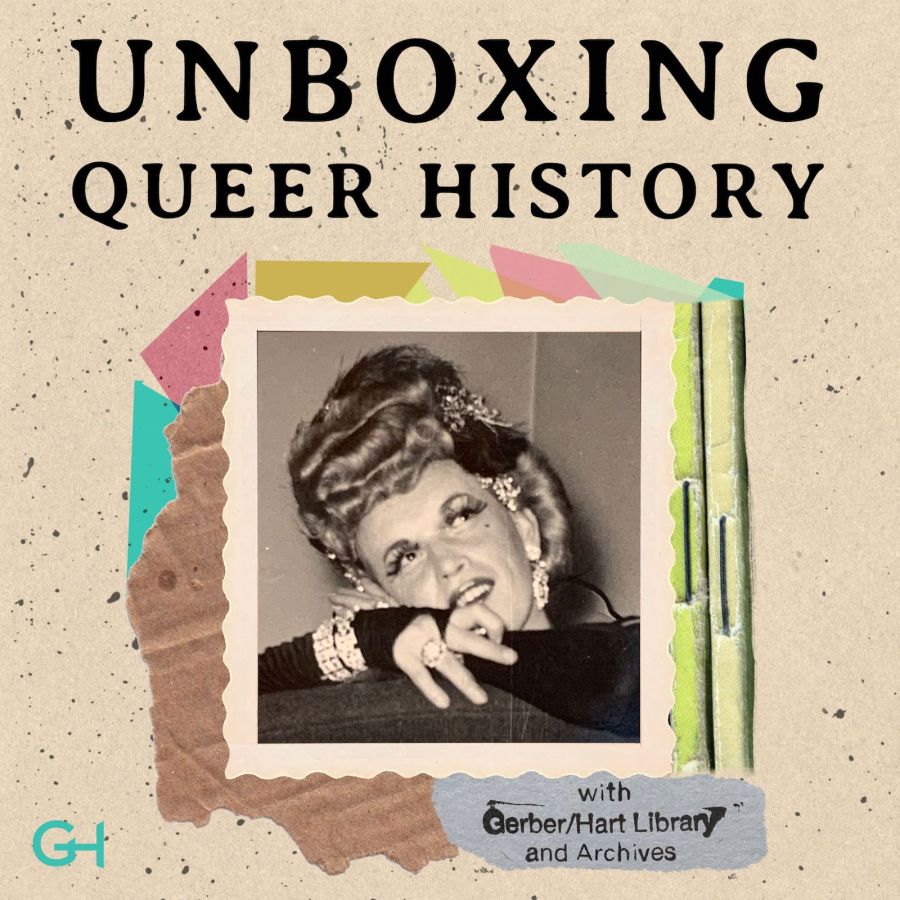

Making these stories accessible requires archivists to consider new media to share their work, especially for people who cannot physically visit the space. The Gerber/Hart team, with audio producer Ariel Mejia, launched Unboxing Queer History, a podcast that takes a multi-sensory deep dive into the archives’ collections. The podcast creates an intimate experience, from hearing the rush of the water while getting fish stories from the Great Angling Lesbian Society to a conversation with Lorrainne Sade Baskerville, the founder of Chicago’s first social services organization by and for trans people. The ONE Archives Foundation also has a podcast project, Periodically Queer, along with YouSpeak Radio, an audio project of intergenerational conversations led by LGBTQ+ youth.

Exploring queer history has even moved some archivists to not just document queer history, but create new conversations. The Black Lesbian Archives features a virtual exhibit about Aché: A Journal for Black Lesbians, a publication featuring artwork, poetry, events listings, essays, discussions, and more by and for Black lesbian creators, and the subsequent nonprofit organization, The Aché Project. Maekdo found the group’s forward-thinking to be an inspiration, particularly around their building the camaraderie between the women of Aché in Oakland and a community in Berlin, including written correspondence, conversation, and organizing transatlantic visits. “It allowed people to not only connect through their idea of thought and their poetry and their artwork and things like that, but being able to use the written word and written text to solidify concrete archival material with each other,” Maekdo says.

Inspired by the work of Aché, Maekdo launched her own publication, Oyé, centered on uplifting the voices of Black lesbians of the African diaspora. She says while she doesn’t want Oyé to be the same thing as The Aché Project, she hopes it will create opportunities for more conversation and global connection in that same spirit.

Via collaborations with artists and other creatives, these archives become spaces for creativity and conversation. For an exhibition for the ONE Archives, textile artist Sarah-Joy Ford created a quilt using pictures of covers from lesbian pulp novels. A team of Chicago artists is currently working with the Gerber/Hart’s Amigas Latinas collection. The Bradbury-Sullivan Center encourages the community to make art from the material through found poetry nights, where they take scans of archival materials and create from that. “What was really cool was it was a really intergenerational event, we had folks 60s+ and people as young as 13 and a lot of the material was around the AIDS epidemic, and it led to a lot of conversations about what it meant to be alive during that time and older people reflecting on loss and younger people having a chance to talk to older LGBTQ people about their experiences through these archival materials,” Gow says. “It was really beautiful and I think it meant a lot to everyone involved.”

LGBTQ+ archives also fight back against the erasure of queer and trans stories by actively building community. Maxine Wolfe says the Lesbian Herstory Archives has “always been outward-looking,” a legacy that dates back to Joan Nestle and Deb Edel hosting the archives in their apartment, where a group of women launched the archives’ first program, a Black lesbian study group. Now, their programs include a children’s reading series called Little Rainbows, the Lez Create Dyke Arts Workshop and LHA’s regular Zoom meetings with other archives to discuss issues in the field and offer mutual support.

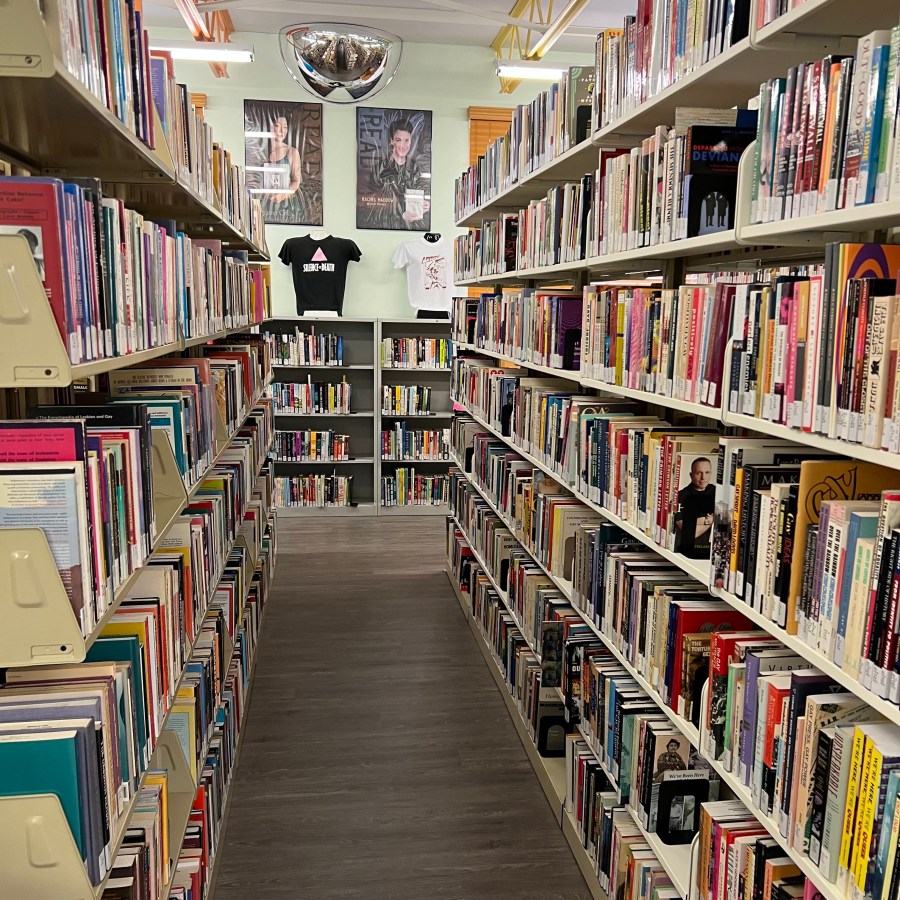

“[The library is] a safe place when you’re figuring yourself out,” says Jen Dentel, Programs and Social Media Coordinator for the Gerber/Hart Library. “If I was too shy to go somewhere like a bar, I could go here.”

Gerber/Hart’s reading room

At the Bradbury-Sullivan Center, the team has added a lot of youth books in response to book bannings, as well as being more intentional about seeking out books by authors of color and trans and nonbinary authors. They’ve received upwards of 40 donations of youth books from authors, and host youth programs and reading groups, many of which are hybrid so people outside the Lehigh Valley can participate. The library doesn’t have library cards for an added layer of anonymity should readers need it. “Books walk away all the time, but our mentality around it is if you really needed that book, I guess you needed it, although we would really like it if people gave them back,” Gow says.

A practical way this commitment to community manifests is through educational programs that counteract the efforts by the right to censor and erase LGBTQ+ experiences and attack queer and trans youth. The ONE Archives and Stonewall National Museum & Archives have both hosted programs for educators on topics like LGBT history for high school teachers and the needs and safety issues of LGBTQ youth. To increase access to reading materials for LGBTQ+ youth, especially those living in areas with regular book bans and censorship of LGBTQ+ topics, the Stonewall Archives recently received a grant from Safe Schools South Florida to begin the process of enacting a digital library where people can check out new books. “It really democratizes access to the library,” Smith says.

Since the passage of the so-called “Don’t Say Gay” bill in Florida, the Stonewall National Museum & Archives has been louder and more explicit about fighting back against this censorship and erasure, from creating merch like “Say Gay” buttons to an exhibition examining the use of code words like “groomer” to marginalize and villainize LGBTQ+ people, to plans for a rally at the old Capitol building in Tallahassee on January 21st in response to attacks on LGBTQ+ people.

The recent moral panic and violent backlash to queer books and family-friendly events does create additional stress and safety concerns for the stewards of these spaces. Although Gow says the Bradbury-Sullivan Center has a lot of support from within the community, their first drag story hour was protested, including protesters physically coming into the event and attempting to question children. “Not only is it terrible having to manage that situation, but [we’ve had] to rebuild trust with families because we couldn’t physically bar this person from barging into our event,” they say. “It does hurt our programs and people feel unsafe sometimes, like I know people will ask us ‘what are all your safety procedures’ before they even come to the library.”

For Gow, the best response is to continue programming and deepen those community connections. “Movements against us have power because we feel separated, isolated, all those things,” they say, “but by being able to create these spaces where people feel connected and able to build connections, [we create] a network of support that can kind of combat a lot of these things.”

The Bradbury-Sullivan Center’s next archival exhibit, due in February 2023, is about Allentown’s nondiscrimination clause, the first in Pennsylvania to include sexual orientation and gender identity, the result of a grassroots effort led by a couple whose primary resource was not money, but community connections. “Being able to see how people have organized helps break down that large sense of dread,” Gow says.

Even digitally, there are concerns about safety, especially as the most vulnerable members of the community often bear the brunt of the right-wing backlash to more queer and trans representation. “The question of who can access these materials becomes really complicated because once things go online, you can’t necessarily control who has access to the materials,” says Collaboratory Faculty Lead Elspeth Brown. “We have a very robust consent process and have a lot of things on the back end, but you can’t control it like in the old days when someone was physically coming into a space.”

“What we come up against a lot is the echo chamber, where we speak to the people who are already on our side over and over again because they’re already with us,” says Ben Smith, a Digital Collections Specialist at the Stonewall National Museum & Archives. “I think our next steps of getting to a better place is to try and get our voices outside of the echo chamber and convince those not within the community to see what we’re going through and further assist us.”

There are a host of other challenges beyond physical and digital safety to building and sustaining archives of LGBTQ+ history and culture, among them the increasingly online nature of, well, everything. It’s important to continue collecting queer history as it happens, but as technology changes so fast, and people create so much media, so rapidly and constantly, Shibuyama says it requires people to be more proactive about saving things.

“There’s very little knowledge out there about how to save that permanently,” she says. “If you create a website, for example, [and] that website goes defunct… then finding the owner of that website becomes harder and harder. Whether it’s chat groups or social media sites, unless you take the time to proactively save them yourself, they just get stored by these companies, and the companies can decide to take it down for whatever reason.”

Shibuyama encourages those looking to preserve their work to save a couple of copies of the photographs or writings or other work you do on your phone or digitally, including on a hard drive, and to organize them in a way you can find them.

Paola Sierra, who has been working with digitizing the Stonewall Archives, says there are challenges with standardization. The Library of Congress system is not as inclusive to queer experiences as they would hope, so they’re filling the gap using the Homosaurus data vocabulary database. The Stonewall Archives also received a grant in 2021 to assist with digitization to help make the archives more accessible and findable.

Even with physical archives and collections, there are quirks and idiosyncrasies that create challenges. Smith says that due to the criminalization and marginalization of LGBTQ+ creators and topics historically and today, some material may come without publisher information or the creator’s name, especially for articles prior to the 1980s, making it hard to pin down exact accurate information.

Oftentimes, pieces of queer and trans history that could be preserved get lost because people saving them pass away or don’t know their ephemera is valuable to the community. “[Our scholar-in-residence] will come into somebody’s house who’s like a figure in the community and they’ll have a box of discs of all the Gay Men’s Chorus for like 10 years and they’ll be like, ‘Ah, do you want this?’ and she’ll be like ‘Oh my god, this is history,’” Gow says.

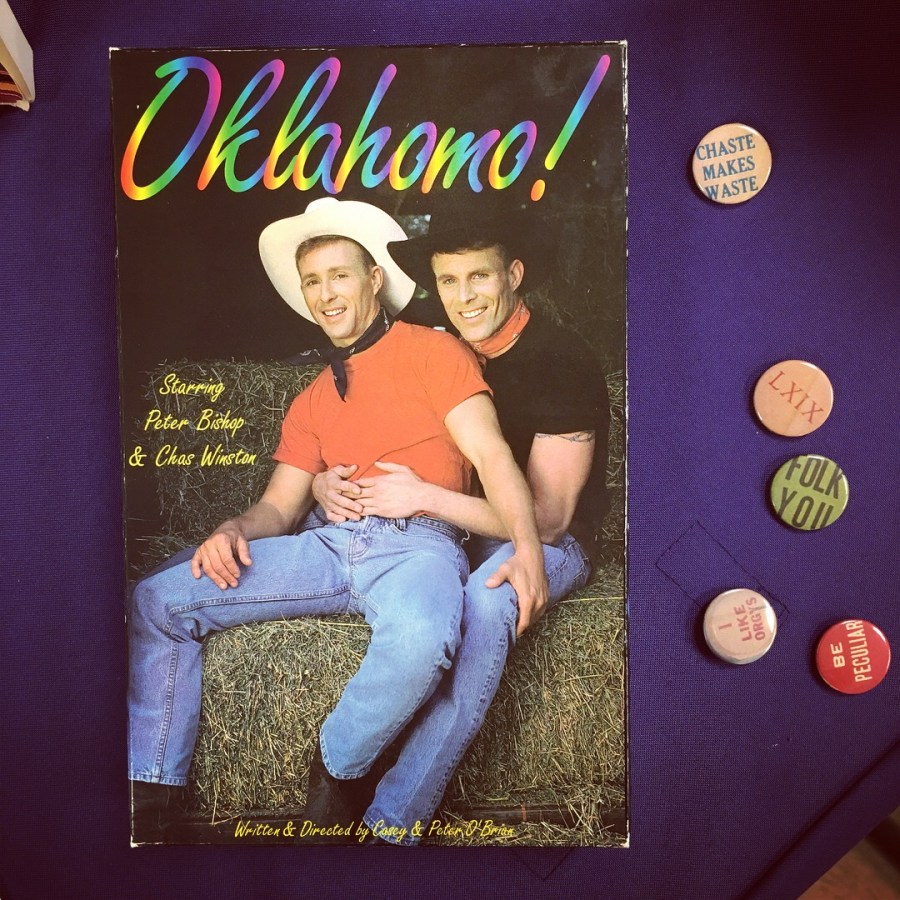

Oklahomo VHS tape from the Gerber/Hart erotica collection

One key ongoing conversation and challenge facing many LGBTQ+ archives and libraries is the reality that their collections, like most mainstream archives, tend to skew towards wealthier cis, white gay men. Archivists and library workers emphasized the importance of building community relationships and trust as an essential step, to ensure any efforts to archive trans, BIPOC and other marginalized queer histories benefit the community rather than just function as an act of extraction.

“We can’t just go out and beg for these collections because there’s a lot of historical harm that white institutions and cis institutions have done to people in those communities,” Sadusky says in the introduction to the Unboxing Queer History episode with Lorrainne Sade Baskerville. “There needs to be some kind of continued connection and collective care.”

The Gerber/Hart team has been working to build those connections, hosting community meetings with LGBTQ+ organizers, and Sadusky says they would love to expand their partnerships to other cultural institutions in Chicago like the National Museum of Mexican Art and the DuSable Museum of African-American History. Interim Gerber/Hart CEO Erin Bell says something she has struggled with is striking the balance between ensuring the archives represent and celebrate the stories of historically marginalized members of the community and strengthening grassroots, community-driven archiving efforts.

Anthony Wright de Hernandez, a Community Collections Archivist at Virginia Tech University, is the coordinator of the Virginia Tech QTPOC Oral History Project, an initiative to collect the stories of queer and trans people of color in the New River Valley and Southwest Virginia “as part of a committed effort to tell the full and diverse story of Virginia Tech’s history.” This effort was born out of another oral history effort, to tell the story of the first on-campus Gay Awareness Week, culminating in “Denim Day,” where students, faculty, and staff were asked to wear denim to show their support of gay rights. The result was an oral history of an important event in LGBTQ+ history in that community, but the voices included were exclusively white and cisgender.

In teaching future archivists, Wright de Hernandez emphasizes that they must consider whose voices and perspectives are missing as much as those presented. “When you’re reading history, you have to keep in mind that somebody chose to preserve that, somebody chose to interpret that, somebody chose what was included and what was excluded, and generally that means whoever is in power is included,” they say. “It’s still the rich white guys who are most likely to get their stuff preserved.”

For Wright de Hernandez, the most important way to begin to build trust is to be an active part of the community, participating in events and getting to know people. To spread the word and build partnerships for the QTPOC stories project, they connect with the LGBTQ+ community center on campus, as well as other cultural and community centers and alumni groups. “I would also love it if they were like, ‘No, I had such a bad time at Virginia Tech, I would never give my stuff to them,’ as long as they tell their story somewhere else, because these perspectives are missing from our history and it’s really important that they be documented,” he says.

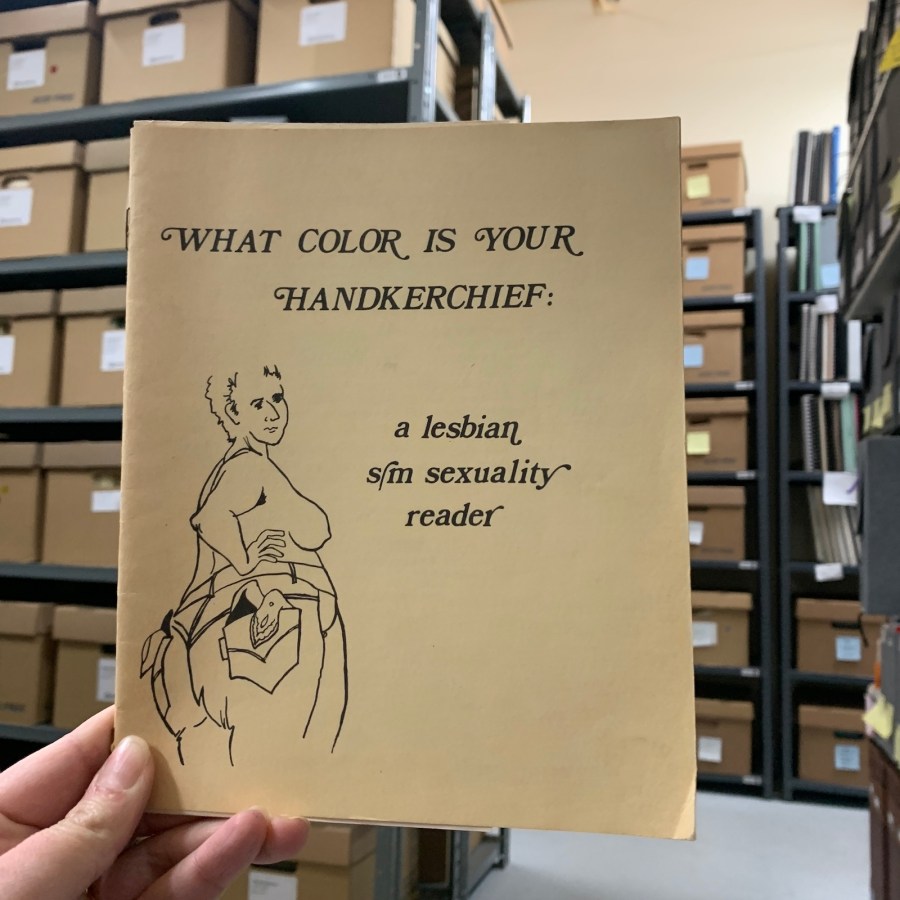

materials from the Amigas Latinas collection in the Gerber/Hart Archives

Krü Maekdo is seeking to respond to the accessibility challenges she found in researching Black lesbian history with a plan to bring the archives directly to the people. Over the past several years, she has been working on a mobile herstory bus tour, which she envisions involving community-led engagement with archives, storytelling, media creation and podcasting, and even markets with local vendors.

“The bus project actually allows us to go directly to people in their homes, in their towns, and interact with the archives themselves, and the people, the elders in some of these locations who can tell the tale about the things that actually happened within their own communities,” she says. “Since we don’t have this access in these libraries or on the Internet, we can actually bring it to people and show them what that looks like.”

The Black Lesbian Archives Mobile Herstory project is “under construction” — plans to launch the tour have been repeatedly derailed by the pandemic. Maekdo is looking for support to bring the tour to life, including securing a bus, tools, and weatherproof storage for archival materials, but also people power, especially Black lesbian storytellers from the African diaspora.

Most of these archives are powered by the work of donors and volunteers. The Lesbian Herstory Archive is an all-volunteer operation; Gow says 90% of the books at the Bradbury-Sullivan Center’s library are donated.

There is power, too, in ongoing personal and communal archives. Krü Maekdo encourages people to get curious and stay connected, creating spaces and projects that share and connect personal, family, and community stories. The more we stay connected, share stories and histories, and build community around them, the harder we are to erase. “You can never erase something that is just so concrete, like the foundation of who we are as a people,” she says. “You can never take that away. You can never erase that.”

Unboxing Queer History is Gerber/Hart’s eight episode 2022 podcast

1. this is both an incredible, necessary story and beautifully reported – thanks lindsay!!

2. i did not realize robin gow was an archivist!! their book a million quiet revolutions is an AMAZING YA novel in verse about two transmasc teens negotiating their understandings of themselves and their relationship through potentially queer american revolutionary war soldiers, so this is really fascinating context.

Here’s a 6 minute video from the ONE Archives in Los Angeles looking at the intersection between gay history and science fiction fandom in the mid-20th century:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6Ig7izqlHLg

This makes me so angry. Not this article. This is wonderful. What makes me angry is this situation. As a lesbian author, I’m tired. It’s exhausting how easy people fall for the grift, the propaganda, the lies, and fill themselves with hate. Most of these people pushing these bans know LGBTQ people or have LGBTQ family or perhaps are themselves even.

They are the ones indoctrinating kids. They are desperately trying to capture the next generation. Liberals have Gen Z. It makes conservatives angry and they know they will never win over that generation. The only way they can do that is through indoctrination in schools with this new generation, even though they are 10 or more years away from voting. Win them over and convince them LGBTQ people are evil, women should be barefoot and pregnant and not working, and POC are less than, and you have a battle for the ages over the next 40-50 years between Gen Z and whatever these current elementary kids are called. It will be ugly and it will define America. I’m just glad I’ll be dead and gone. I always wanted to prolong life. Never wanting to die but all this hate and backwards thinking, I’m ok getting older now. More than ok. It makes me sad actually but that’s for another day.

Thank you for this. In your research were you able to see if Canada & England also had multiple archives out of curiosity?

thank you so much for this piece. xoxo

this is incredible! thank you lindsay for sharing the words of these curators and archivists with us

one quote that i’ll be thinking about for a while is ““Books walk away all the time, but our mentality around it is if you really needed that book, I guess you needed it, although we would really like it if people gave them back,” Gow says.” the amount of self exploration and discovery that takes place in the stacks is so incredibly special

Thank you so much for the clear time and thoughtful effort you put into capturing the importance of spaces like these. Living in Chicago and having the Gerber-Hart Library as a resource makes me feel incredibly lucky, and I am so glad that the work they do is being given the spotlight.

I will also say the Leather Archives and Museum (just down the street from G-HL) is also an amazing resource of the history of the s/m scene and queerness as well, definitely worth mentioning and checking out :-)

Really appreciate this, thank you!

What an excellent piece of journalism! It is so bittersweet to read about how our history has needed to be preserved as some people try to erase us, but how hopeful that we have so many excellent archivists on the job of telling preserving and telling these stories. At the start of the article, I was immediately hoping to hear about digitizing efforts but it was also interesting to hear some of the concerns and pitfalls surrounding it. Wonderful work, may we all continue to ensure our stories are told.

Thanks for shedding light on the importance of queer libraries and archives in preserving marginalized histories. It’s crucial to cherish and learn from such institutions, especially in times of erasure. I was working on the project on the same topic and experienced troubles with formatting, so Research Guide provided essential guidance on structuring. I can conclude that these libraries protect LGBTQ+ narratives with clarity and impact, ensuring their voices are heard and understood.