Picture this: you’re on a scooter, whisking down Boulevard Montparnasse. It’s a spring night, and you’ve got a silk scarf tied around your neck to escape the chill. There are cigarettes in your pocket, cognac and coffee in your belly. You’re on you way to meet a mysterious woman you glimpsed at the opera — or an enchanting woman you met at her underground theater performance — or any intriguing woman period. You are not from Paris originally, but you are one of its denizens now and it folds you close, balances you on its tongue.

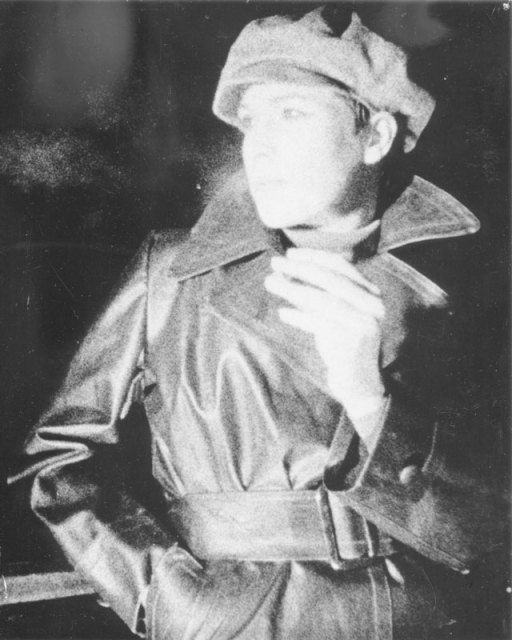

Image curtesy of Renate Stendhal’s private archive

Paris is a city that looms mythic in the imagination. It has come, in the last hundred years or so, to represent a kind of lifestyle that is one of creative, cultural, and romantic freedom, an elusive blend of passionate joie de vivre and moody elegance. And while the truth of life there now probably feels closer the life in many other metropolitan cities, the Paris of decades past is waxed particularly shiny. It shook off the trauma of WWII to become a haven for writers, artists and intellectuals; underground movements, student protests, political and sexual awakenings.

Image curtesy of Renate Stendhal’s private archive

“Paris was different from the other major European cities I lived, worked in, or visited. [It] had a vastly permissive sexual culture to begin with, and the rebellion of women threw over anything and everything that was still left to corset, restrict and cripple them,” writes Lambda Literary Award-winning writer Renate Stendhal, who was born and raised in Germany and moved to Paris to study ballet at age 23, in an email to Autostraddle. She ended up working in underground theater and multimedia, and started writing as a cultural correspondent for various German news outlets. This landed her smack in the middle of Paris’s arts and culture scene during the 1970s–80s, a distinctly active and experimental period in its history. It was also where, and when, she began to explore her identity as a lesbian. She writes:

“In the early seventies, lesbian and bi-sexual writers, artists, and intellectuals were at the forefront of this gigantic wave of empowerment. Many of them were […] neither butch nor femme (or equally both), setting the tone and style of the movement in a romantic, erotic androgyny that was seductive and irresistible. […] By the end of the seventies, women were in fashion: every Parisian woman, gay or straight, fell in love with women as if it were the most natural thing in the world.”

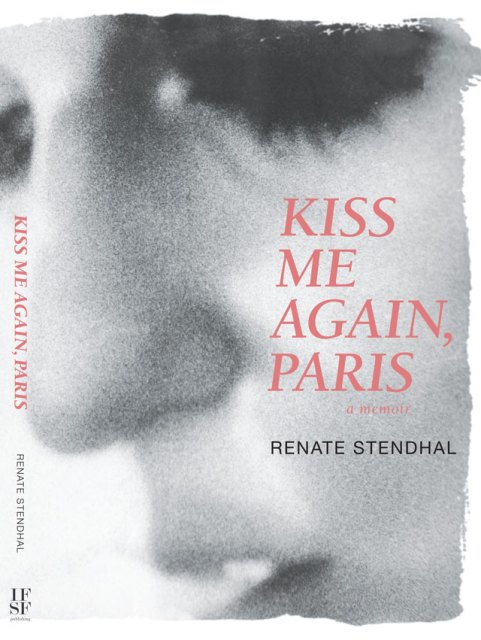

In Kiss Me Again, Paris, which arrives today from IFSF, Stendhal revisits this era of her life. Her memoir is notable for a variety of reasons: it’s a window into the gay female melee of the moment, and she has a particular way of recalling her encounters with luminaries. Some she names outright, like Meret Oppenheim and Pina Bausch; others’ identities she keeps under wraps. It’s a tactic that places the book in a category Stendhal playfully refers to as memoir à clef, a twist on the roman à clef: a novel with “keys” to uncovering the real in the fictional. (One famous example is Simone de Beauvoir’s The Mandarins, in which Jean-Paul Sartre and de Beauvoir herself are hidden within the characters.) She identifies it as one way to retain some existential protection for herself within a narrative that is at times very intimate and revealing, but also as a way to protect the friends, lovers and mentors who appear there as well.

It’s like a murder mystery, only instead of trying to figure out who died, you have to figure out who everyone is — and who they’re sleeping with.

“You could say that my invented genre of ‘memoir à clef’ plays with an erotic game, a voyeur game, within a true story. Enough is revealed to pull most readers through the plot of suspense and mystery without having to stop to wonder. But if you are a Paris insider, if you have been there in the circles of gay and bi Parisians and expatriates at the end of the seventies, you will see through the slight veils and recognize everything. If not, you are invited to make up your own erotic ‘keys,’ open the seven doors of secrets, and get kissed behind each one of them.”

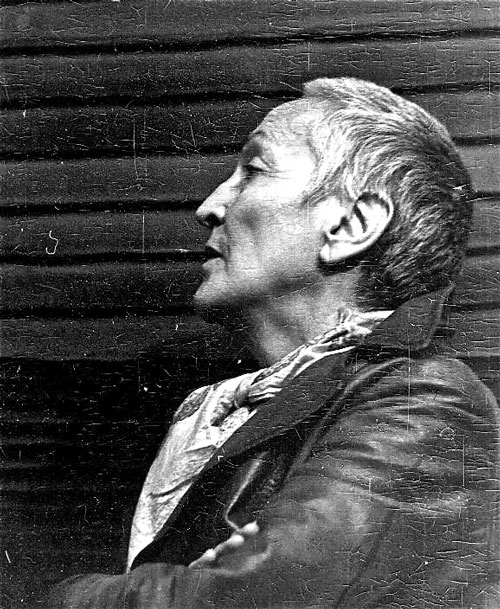

Artist Meret Oppenheim at a poetry reading (image curtesy of Renate Stendhal’s private archive)

It’s an interesting way to create a meta-game out of the larger questions of identity and belonging that circulate in Stendhal’s portrayal of her younger self, who often struggles with the larger historical and political implications of her German upbringing once she lands, relieved, in a country with “shame over the Nazi occupation and collaboration still festering in the background.” She explores what it means to be a chosen exile, and how that affects one’s creative life as well:

“Don’t you think there’s always more than politics? Something entirely personal about chosen exiles?” She fingered a filtered cigarette out of her packet. “Wanting to get away from…” She nervously flicked the wheel of her Bic with her thumb. “From one’s own story. In order to rewrite that story.” Her lips closed around the cigarette. Her Bic didn’t light.

Stendhal now calls California home. When asked to reflect on the current political moment of the U.S., in light of everything she’s seen up to this point, she answered that she trusted young women, gay and straight, would fight back against this roll-back of progress, and that “the purpose of Kiss Me Again, Paris, is to say: remember a time when almost everything women fought for and dreamed of, seemed to be given, or to be in reach. Remember!”

A short escape to the City of Lights, then, is certainly a welcome one.

This sounds so good! Great review.

It is a TREAT I highly recommend it.

This book sound charming. Is there any pictures in there, or ways to view some of her images?

@needlesandpin There are SO MANY MORE PICTURES IN IT! Not sure where else her images appear, but this book is a great place to start if you wanna see more.

This sounds really cool, and given that I’m moving to Paris in January, I’ll definitely be reading it! Thanks for a fab review :D

That sounds like a DREAM. This is definitely an excellent primer.

I got it for Christmas! Excited to read!

Thank you for this! <3

This review was BEAUTIFULLY written. (Excited to read the book, too!)