all archival images courtesy of Invisible Histories

Although it has become a lot easier to access the stories of our LGBTQ ancestors over the last 20 years, there is still so much missing from how we narrate our queer past in the U.S. Many of our community traditions, like our annual Pride celebrations, harken back to sanitized and widely-circulated moments in our history that happened in what people assume are the most “progressive” parts of this country (namely, New York City and Los Angeles). Naturally, pointing this fact out to people is always a daunting task, especially when it comes to discussing the queer history of the South. Many will incorrectly assert that, by nature, these more “elite” geographical locations have been and are much more radical spaces of possibility than the South. Or they will, even more egregiously, write the whole region off as conservative, backwards, unfriendly to difference, and utterly unsalvageable. The framing of the North as forward-thinking and the South as a land of systemic horrors did not emerge without some basis in historical truth, of course. But it also fails to paint an accurate picture of both regions and their impact on both queer history and the history of all marginalized people in the U.S.

The South and its people — whether you want to hear it or not — have been at least as equally important to the struggle against systemic oppression, if not more than, the North and the West. Collectively, the states that make up the South are home to more Black people, more people of color, and more LGBTQ people than any other region of this country. It’s true that the region is also still plagued by the leadership of white supremacists who have been able to keep themselves in power through the mechanisms of racial capitalism and exploitation. But how is that any different from the rest of this country?

By metrics alone, without even mentioning the specific evidence that backs this up, the radical possibilities and achievements imagined in and born in the South have been pushing the other regions of this country forward for, at minimum, the last 180 years. Our issue has never been a lack of organizing and putting that organizing into action, but rather, a combination of more explicitly fascist governance, exploitative resource extraction, abandonment by the Federal government, and a nation of people willing and ready to act paternalistically about the South. Or write us off entirely. As a result, the many accomplishments of marginalized people of the South are used as cautionary tales to ramp up sympathies about the people who do live here. Or those accomplishments go completely unnoticed. When we’re trying to piece together a more thorough understanding of LGBTQ life in the U.S., this happens excessively. Queer and trans people in the South are rarely seen or discussed as courageous, powerful, or even historically relevant. Instead, we’re assigned the status of long-suffering, agency-less fools who should move away from these places in search of a better life.

As Josh Burford, co-founder and co-Executive Director of Invisible Histories Project, puts it, the South “is the story that people tell to themselves as a way of talking about how ‘good’ they are. We exist as the counterpoint to remind them of how ‘well’ they’re doing.”

“The American South is the most queer place, but we’re also the most racially diverse,” Burford continues. “And so it’s just straight up old school white supremacy to dismiss the South. So, the wholesale dismissal of the American South…it’s lazy, it’s racist, it’s classist, and people only want to live in the South because it’s apparently cheaper to live here than to live in New York.”.

Invisible Histories was created as a direct response to this unwillingness of others to see the full breadth of experiences lived by people in the South, combined with a desire to show LGBTQ people in the South they are part of a long lineage of queer and trans organizing in the South.

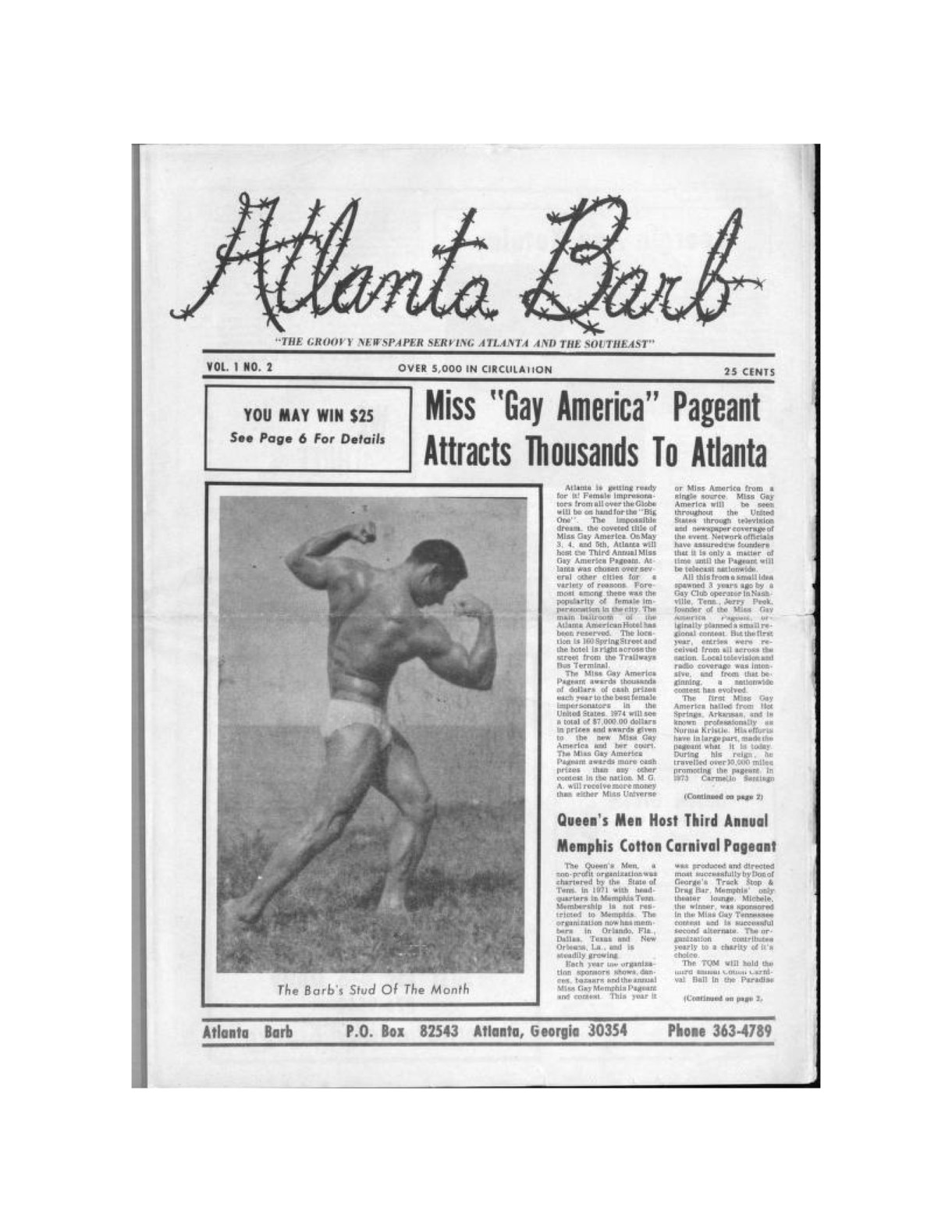

1974 issue of The Barb, Atlanta’s first LGBTQ newspaper ever.

Invisible Histories is dedicated to archiving, preserving, and telling the stories of LGBTQ people in the Deep South. They practice regionally-specific archiving that collects, stores, and creates access to materials related to LGBTQ life and resistance in the South that is dependent on not only existing archival collections in academic and library spaces but also on the people and their organizations who actually lived that history.

On their website, they write that they believe “archiving is resistance to oppression and history leads to liberation.” Their mission — beyond collecting these materials — is to make them highly accessible to all LGBTQ people in the South. Their website explains further, “We strive to break barriers between organizations and their local communities to ensure that preservation and research exist in a co-productive and relationship centered way. […] We focus on providing education around the Queer South to those within and outside the region through speaking, exhibiting, online materials, and publications.”

Burford, who was born and raised in Alabama, tells me the seed was planted for Invisible Histories when he started teaching at the University of Alabama in 2004. He received a graduate degree in American Studies and began teaching Queer History at UA soon after his degree was conferred. Like many historians teaching queer history at the time, the materials for his classes weren’t focused on the queer history of Alabama or any of the other parts of the South, much to the dismay of many of his students.

“I got the same feedback at the end of every year, which was that my students were enjoying the class, but they wanted to know more about local history,” he says. “And I hadn’t a clue. At the time I was in graduate school, there were maybe 10 books about the queer South, and a lot of them were oral histories, which are fine, but missing that evidence-based stuff.” This feedback from his students prompted Burford to enroll in another graduate program in Library and Information Sciences so that he could begin doing archival work.

During his time in the program, Burford built two LGBTQ archives at UA, then took a position at the University of North Carolina–Charlotte and continued his archival work with the city of Charlotte and with UNC. It was shortly after he began working in Charlotte that his friend Maigen Sullivan, co-founder of Invisible Histories, called him back to Alabama. “She was working at the University of Alabama Birmingham and brought me down to do a talk on the queer South,” Burford says. “And we were just chatting, and she said, ‘Do you think that we could do what you do in Charlotte, but for the state of Alabama?’ And I said, ‘Well, we could, but we’re going to have to come up with a way to do it.”

In 2016, Burford and Sullivan started doing this queer archival work for the state of Alabama in earnest, and in 2017, Invisible Histories was officially granted non-profit status so they could continue doing their work. By 2018, Burford and Sullivan were able to pick up their first collection from Alabama and, as of this year, they’re up to over 150 collections, most of which have been entered into the databases on their website and some of which are currently digitized for people to access easily.

Burford says that if everything goes according to plan, they’ll have 200 collections in their database by the end of 2024, which is a huge feat for a project that’s less than a decade old. “I knew that no one had been collecting queer history really in Alabama in any methodical way,” Burford says. “And so, I knew there were collections. I just had no idea how many there were.”

June 1992 issue of WimminSpace News out of Jackson, Mississippi

In 2019, Invisible Histories got a grant from the Mellon Foundation that required they begin collecting in more places. They added Mississippi and Georgia and recently expanded into the Florida panhandle. “It’s just been a wild ride to be able to not just find this many collections, but also the scope of these collections and the dates,” Burford says. “Our oldest thing is from 1920.”

As Invisible Histories has grown, their mission and their focus on community-responsive archival work has grown with it. “I’ll say this as a person who’s been archiving a long time, but archives are designed, I think, traditionally, for materials, not for people,” Burford says. So, Burford and Sullivan made it part of their mission early into beginning Invisible Histories to make sure the work they do is directly connected to the communities they work in.

Many people tend to think of archives as being connected to universities, academic libraries, or big governmental institutions, and they usually don’t realize there are archives in public libraries or in community-based historical societies. As Burford explains it, people sometimes have a “psychological barrier” to accessing spaces like archives, which seem imposing and inaccessible. And in addition to that, they usually don’t know where to start when they’re interested in a specific topic or issue.

“The way we have organized archives, again, are organized for archivists, not necessarily for community people, which is why when you’re doing queer and trans history, it’s so hard to find stuff because you just don’t know who processed that collection,” Burford explains.

In response to that, Burford, Sullivan, and the rest of the people they work with have dubbed Invisible Histories a “people’s collection.” “It’s so important for us as Invisible Histories to constantly remind people that this is a people’s collection,” Burford says. “We might be housing them at a university, but we’re doing that with the knowledge that our responsibility is to figure out how to get you in there, get you through the door, demystify the process, and then at the same time, try to push archives to do things differently.”

He explains further that a lot of the historical society archives and other institutional archives are built around white supremacy. They’re an attempt to “protect” that history from being “overrun” by other people’s stories, which means they’re not built for someone without specific archival knowledge and education to use. However, that’s never been the way that queer people practice archiving.

Burford explains, “One of [Sullivan’s] favorite things that we find is a folder that just says, ‘history’ or ‘articles’ on it where people were just clipping out everything they could find with the word ‘gay,’ ‘lesbian,’ ‘bi,’ or “trans” and then putting it aside. I think that so many older people were collecting to give themselves a sense of community and to save it for someone else. So there is an archiving tradition built into the experience of Southern queerness, which you don’t see in a lot of places that have turned over their archival collection exclusively to institutions.”

“We’re doing the damn work down here. It matters. I don’t know why people can’t see this.”

This model has helped inform all of the work Invisible Histories has done and is currently doing. Since they’re mostly working in rural areas that have very little funding for their own archives, they aim to help the people in these places create them through partnerships with public archives and universities. “We want to work with existing archives, train them about how to work with community people, train the community how to work with them, and then build in that safety through our partnerships so that the material is always available to the public. It’s a different way of doing archiving, but not different for queer people,” Burford says.

Much of how queer people have organized, performed actions, began organizations and social clubs, and gotten together has been by passing information to one another through secret channels. Similarly, as Burford points out, much of how we’ve gotten the stories of queer action, resistance, and life is through oral storytelling and people casually keeping these stories to pass onto others who might find them useful. Our process for sustaining our lives throughout history as queer and trans people has been through these actions. We know something or don’t know something, and we find people to talk to about it. This is how Invisible Histories has been able to build their collections outside of connecting with institutional archives. Burford tells me that he and the rest of the Invisible Histories team are often able to build collections simply by connecting with people in the communities where they work.

“There’s no such thing as one collection,” Burford says. “Every collection generates new collections each time. Conversations go out into the wild without us. People might be having brunch or be at a party or at a softball game, and they say, ‘Hey, have you talked to Invisible Histories? Because you should really do a blog on X, Y, Z.’ And then, things start coming in. I’ve also been surprised at how clear the line is between contact and collection that comes through social media. We’ve had several instances where we have just put on social media, ‘Hey, came across this reference. Does anyone know what this is? Where could we find it?’”

Through these connections, Burford and the team have been able to uncover a myriad of formerly hidden parts of queer and trans history. He’s received an entire collection of historical materials from Atlanta through a trans man in his eighties who actually lived through the stories the materials tell. They’ve uncovered materials from a queer Mardi Gras crew out of Pensacola, Florida named the Krewe of Zeus just through putting word out that they found a reference to the krewe’s existence at an archive in the Florida panhandle. From looking through a LGBTQ fundraiser book from the 1970s Out of the Closets, Burford learned of a gay publication called Gay Seed out of Huntsville, Alabama, and he was able to collect some of the first issues through another person who found them in a local thrift store. That connection also brought him the opportunity to speak with the original publisher of the magazine. Similarly, he explains, all of the material on the Emma Jones Society of Pensacola that is currently housed at the University of West Florida was found in a box labeled “Emma Jones” at a thrift store in Panama City, Florida.

September 1976 issue of Lesbian Front out of Water Valley and Jackson, Mississippi

Burford tells me that after he appeared on a podcast, a person from Montgomery, Alabama sent Invisible Histories the photos and diary of his gay veteran uncle who was stationed in France during World War II. “That’s that Southern grassroots feeling of ‘Who do you know that I should know?’ and ‘How do we connect those people?’ And we use that to help create our collections,” Burford says.

While it might seem from the outside that doing this kind of archival work can’t and won’t do much in helping marginalized people achieve liberation, that couldn’t be further from the truth. We’ve seen throughout history — and we’re seeing it now — how fascist and authoritarian forces attempt to eradicate communities through the destruction of those communities’ educational, research, and archival centers. The destruction of historical documents isn’t just an attempt to punish communities. Rather, it is an attempt to make sure those communities are pushed further to the margins and that people who might benefit or learn from those materials have no access to them. Not only are the experiences of these communities erased, but as a result, people cannot learn from the successes, failures, joys, sadnesses, and praxis of the people who came before them. “It’s too difficult to dig out from under your own oppression if you feel alone and disconnected and have no models for how you might liberate yourself,” Burford explains.

The majority of queer history up until the 1990s was actually quite radical. Queer and trans people weren’t just fighting for “acceptance” and equal rights under the law. Resistance to the racist, heteropatriarchal culture of the U.S. as a whole was a large part of our story. Queer and trans activists were, of course, fighting for their rights, but they were also protesting the American war in Vietnam, organizing on the frontlines of the Civil Rights Movement, the workers’ rights movement, and the immigrant’s rights movement. They were well aware that their oppression was directly linked to the oppression of all marginalized people in the U.S. and abroad. They didn’t see their struggles as unique in the course of human history. They saw their systemic oppression as part of the fabric of all marginalized people’s oppression. As time went on and the most powerful people in our community became more infatuated with the notion of queer assimilation into these systems, these stories became whitewashed or got thrown to the wayside. And more distinctly, the history of the queer South became nothing more than a ghost story.

“For us, archiving is resistance because we are resisting the notion that people don’t think we’re here in the South,” Burford says. “We’re resisting the notion that we don’t exist. We’re also resisting the notion that we were never a part of a larger community and this idea that queer Southerners were/are behind. That is a calculated fascist decision to isolate us in this place. Also, quite frankly, looking at our history should, when it’s done correctly, show you the connectivity, that connective tissue between struggles. And when you’re learning your history, you can also start to understand shared oppression. So, if it’s this bad for me and I’m a white able-bodied person, what must it be like for a queer person of color or a trans person? And so there’s that learning that happens that creates more community. It creates more bonding opportunities and more opportunities to learn and to dismantle.”

And that’s what Invisible Histories is here for. The larger LGBTQ community still has so much to learn about our history and, more specifically, the radical potential granted to us through the actions of our elders and ancestors. “We’re doing this because we have this beautiful, rich history of resistance, political organizing, and community development,” Burford says. “Just thinking, alone, about the work that must have gone into creating grassroots organizations for HIV outreach in the 1980s with no funding. Nobody gave a shit, and we were dying. That’s the kind of stuff that can inspire us now. When we are literally living in a fascist state, and not just Southern states, but a fascist country that wants to destroy us. This history can provide those lessons. It can provide us with opportunities to learn, to emulate, or to do the exact opposite that somebody did. We’re not advocating for a political person or a political group. What we’re advocating for is the liberation of our community.”

December 1972 issue of UpFront Magazine out of Pensacola, Florida

With this in mind, Burford and the rest of the Invisible Histories team is keeping in line with the traditions of our elders and ancestors and building their space to be one that is easy for queer and trans people to access, completely free of the financial or psychological barriers that might prevent them from accessing these materials in other places. They want Invisible Histories to be a “landing page for LGBTQ people who have questions at any level.”

As Invisible Histories grows and changes, Burford is adamant that more people not only use the resources they’ve uncovered, but also tell Invisible Histories about what’s missing and, if they can, how to get it. “We want to create as broad of an amount of resources as we can so that people can come and find what they want,” Burford says. “And if they can’t find it, we want to be a place where they can ask us. We want a community. We want a library where you go in and you learn and you exchange ideas, and we grow, and we fill in the gaps. We want the community’s input and their help.”

Like the LGBTQ people and communities who came before us, Invisible Histories is doing work that will also help ensure our survival — in the archives and outside of them. And although we’ve achieved what some may argue as some of the most pivotal wins of LGBTQ life, we obviously still have a lot to fight for. Both queer Southerners and queer people all across the U.S. can benefit from using the resources provided by Invisible Histories to imagine, create, and fight for new possibilities for queer and trans people everywhere. After all, as with much of the civil rights history of this country, many of the major political wins for LGBTQ people came from people organizing in the South. And people can’t keep dismissing that fact when organizations like Invisible Histories exist.

When asked what people outside of the South can do to support the work of Invisible Histories, Burford puts it very bluntly:

“You know what we need? We need your money. If you want to support queers in the American South, write a check, send a Venmo. You’re sitting on a giant pile of money living in a $5 million apartment that has one room in it in New York? Good for you, girl. Walk down to your bodega and then walk to a Wells fucking Fargo and send us a check. Don’t sit around all day hemming and hawing and making sad faces at us. We’re doing the damn work down here. It matters. I don’t know why people can’t see this.”

This piece is part of UNDER COVER, an Autostraddle editorial series releasing in conjunction with For Them’s underwear drop.

As a queer Texan I love and appreciate this so much!

Thank you so much for reading. During our conversation, they mentioned the possibility of expanding to places like Texas in the coming years. Pretty awesome.

thank you for this, what a great read

Thank you for reading!