I saw Hustlers the Monday after the movie released, with about a dozen of my coworkers. Normally, this sentence wouldn’t raise any eyebrows – the hype around it has been building for weeks – but my coworkers are strippers, and in the movie theater, we took up an entire row and then some. Starring Jennifer Lopez as a strip club veteran Ramona and Constance Wu as Destiny, the babystripper taken under her wing, Hustlers is a highly fictionalized account of “The Hustlers at Scores” by Jessica Pressler, which ran in New York magazine in 2015 and described the real life credit card scamming ring run by Samantha Barbash and Roselyn Keo, whose lives inspired Ramona and Destiny, respectively.

In the week since the movie debuted, publication after publication has reviewed it. Some have called it “brilliant.” Others have missed the mark entirely. Relatively few, however, have centered the reactions of strippers and other sex workers themselves. This is unfortunately unsurprising: every so often, Hollywood decides to take on sex work and attempt to tell our stories, and more often than not, they get it wrong, painting sex workers as “fallen women,” as victims or villains, objectifying us either through glamour or degradation, and rarely allowing non-sex working audiences a glimpse into our subjectivity and humanity.

Hustlers, I’ll admit, did better in this area than sex worker movies that preceded it. (Showgirls has a reputation for being particularly bad – the kind of movie that you only watch with your coworkers as a campy sleepover drinking game and wake up regretting in the form of a monstrous hangover. No stripper on this rapidly decaying earth would ever lick a pole.) There were elements the movie, written and directed by Lorene Scarafia, got right: the look of helpless rage on Destiny’s face as she pays out her house fee to the club, to tip the bouncers, DJ, house mom, and the extra money she has to shell out to grease the palm of whichever nameless man is choosing to exploit her in that moment, likely leaving her with less than she walked into work with. “House fees are no joke and tip outs are no joke,” one stripper I spoke to, Kirah, told me. “If you don’t tip out enough, you don’t get taken care of by management or DJs or waitresses/bartenders and it feels like shit sometimes.” But there were good things the movie got right, too: the stars in Destiny’s eyes as she watches Ramona’s stage set for the first time – a expression of rapt attention, exhilaration, and lust that I still get when I see one of my coworkers being especially enthralling on stage. “I loved the representation of being a baby stripper. It landed with me so hard! I feel that way in every new club I work at, and I definitely felt that way in Manhattan! I would watch these older, more experienced strippers doing their thing and making piles of money and I wanted the magic secret to making that happen,” Kirah said. The scene that made my heart sing the most, though, was unbridled joy and silliness of the strip club dressing room, with conversations between strippers being some of the most candid, heartfelt, and most ridiculous, conversations you’ll ever hear anywhere.

There was also a lot about the behind the scenes of Hustlers that Scarafia tried to get right: She cast actual current and former sex workers in the movie, for example. Not just Cardi B., but also well-known stripper, artist, and comedian Jacq the Stripper, who had a small part in the movie and was also hired as comfort consultant to ensure the authenticity of the strip club scenes and the portrayal of strippers in the movie. The movie was filmed at Show Palace in Queens, and dancers there were given the opportunity to audition for roles as extras specifically because filming would shut down the club, and they would otherwise be out of work for a week. Dancers who worked as extras on the film were paid $1600 a day to work from 3pm-7am – not an amount to sneeze at, to be sure, but, as some dancers pointed out, also somewhat less than they might be making on a good night at the club (and less, when you do the math, than the $175 an hour that SAG actors make as extras).

But in the days and hours leading up to our movie outing, there were a couple of times that I found myself reconsidering whether or not I wanted to spend my money on a ticket. The fact that only some of the Show Palace dancers were hired as extras in the movie didn’t sit quite right with me, for one thing. According to well-known stripper activist Gizelle Marie, the organizer of the #NYCStripperStrike, which called attention to racism and colorism in hiring practices of New York City strip clubs, workers at Show Palace were given two weeks notice that their club would be shut down for a week for filming, and were given the opportunity to audition to be in the movie. But not everyone who auditioned was hired, and perhaps not everyone wanted to audition – or couldn’t risk being outed even as an extra. I know from my own experience that auditioning is a nerve-wracking process; you have to have a thick skin to do it, and two weeks isn’t a lot of turn around time to find a new place to work if you need to. For someone like me, who works only two nights a week because that’s all my non-sex worker job schedule allows (but doesn’t pay me enough not to have to strip at all), missing a week of work because a movie shut down my club would seriously mess with my ability to pay my bills that month. And while some, like Gizelle Marie herself, certainly have a point that more than anything else it is the club’s responsibility to advocate for dancers’ lost wages when something like this occurs (especially because the club definitely made a handsome paycheck in renting out for filming), I think it’s also true that in a movie created with sex workers in mind should have reserved some portion of that $20 million dollar budget for the dancers they knew would be displaced during filming.

Before our movie night, I also observed some stark differences between how the movie was received by sex workers and by non-sex workers. Non-sex workers seemed to be crowing about how much money the movie made in its first weekend – a cool $33 million – and rumors abounded that J.Lo would be tapped for an Oscar for her performance. Sex workers, however, were focused on other details – like the dancers who missed work during production; or the fact that a professional dancer from Cirque du Soleil (hashtag not a stripper) was hired to teach Lopez to pole dance; or the fact that in preparing for her role as Ramona, J.Lo mined real life dancers’ real experiences for an insulting and paltry sum. J.Lo even talks about visiting a strip club in this interview, describing how she “watched the ladies do their routines, met with them backstage, and talked about what it was like to have a career as a dancer,” in order to learn how to perform the role of Ramona “authentically.” But writer, sex worker, and sociology grad student @ethical_pute revealed in a Twitter thread that, according to strippers who were there, J.Lo only compensated the dancers – whose lives she was studying to successfully do her job – a grand total of two hundred dollars. In an interview for The Breakfast Club, A. Rod corrects this number to $500-$600 dollars per dancer, but even if I were in the business of believing the word of a rich man over sex workers, that’s still frankly a pathetic amount of money for someone worth literal millions.

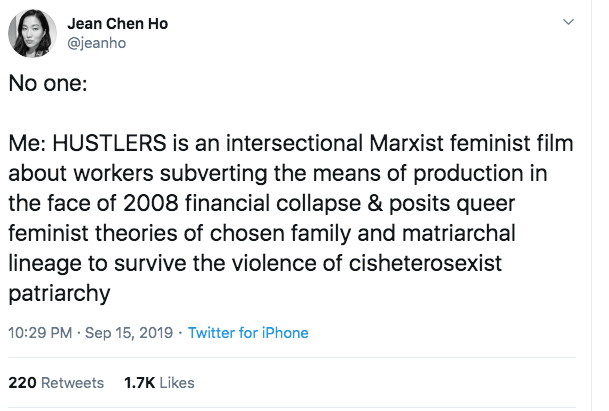

This makes J.Lo-as-Ramona stating the unifying theme of the movie somewhat cynically ironic for me. Ramona, in her heavy New York accent, lays it out like this: “This city, this whole country, is a strip club. You’ve got people tossing the money, and people doing the dance.” It’s a statement that feels like an indictment of capitalism, and one the resonates uniquely with a certain subset of internet millennial (myself included), weary of our exorbitant student loan debts, low paying entry level jobs, and unpaid internships. In fact it’s the rallying cry that many non-sex workers have cheered, perhaps in its nod to Silvia Federici’s “we are all prostitutes” in Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction, and Feminist Struggle, and echoed again in Lies: A Journal of Material Feminism: “All work is prostitution and we are all prostitutes. We are forced to sell our bodies – for room and board or for cash – in marriage, in the street, in typing pools or in factories.” While exposing this rhetoric may feel new and invigorating for civilians – as seen in PhD candidate Jean Chen Ho’s tweet in response to the movie below – it’s nothing new for sex workers, who for generations have known the price of things like sexual and emotional labor, beauty, and care, especially as they operate under capitalism.

And the fact remains that we are not “all prostitutes” (a term that full service sex workers – those who include penetrative sex among their services – will tell you is a slur, along with “whore,” that should only to be reclaimed by full service workers themselves) – as much as capitalism coerces each and every one of us to sell our time and labor in order to live. This was clear as day in Hustlers, where signs of lateral whorephobia (or stigma from theoretical “no-contact” sex workers like strippers towards full service workers) were rampant. In one scene, Destiny and Ramona looked down their noses at the idea of grinding on a man’s lap during a post-recession lapdance, having been used to instead slowly stripping and gyrating from all the way across the room. Hello! The word is lapdance. In others, Destiny freely calls other sex workers “junkies,” another slur right out of Roselyn Keo’s mouth herself, making the hierarchy of workers she deems “worthy” of respect and those who are not all too clear. This representation of what is known as “whorearchy” is, unfortunately, to some degree accurate and authentic. I know plenty of strippers who turn their noses up at the idea of doing “extras,” even going so far as to say that strippers who work “dirty” (another stigmatizing term) are “ruining” the game for everyone else. But the fact remains that customers who are seeking ‘extra’ services will be seeking them in the club whether you offer them or not, and if someone’s hustle is different from yours, a skilled hustler can work within those conditions: the customer who wants extras was never going to be your customer anyway, as sex worker, educator, and advocate Expensive Spencer explains.

Portraying whorearchy in the movie in and of itself wasn’t a deal breaker for me, but upon investigating some of the viewpoints of the actors and real life “hustlers” who inspired the story, I became convinced that the examples of whorearchy were an uncritical byproduct of a story written by non-sex workers whose research into the industry was cursory at best. In an interview with Vulture, Lopez explains some of the examples of whorearchy that the strippers she interviewed ascribed to, saying, “I also asked if it was common to go home with any of the guys from the club, and they were quick to correct me. It was ‘No, no! I am a dancer, not an escort.’ There is a strict line. There are boundaries.” This sentiment – that strippers who offer extras work “dirty” or are “less than” strippers who don’t – is also reflected in the movie, and creates a hierarchy that harms full service workers, who are often the most vulnerable members of the sex work community, particularly if they are queer, trans, or of color. (Black trans sex workers are the most vulnerable members of the community of all.) The scam that Ramona and Destiny run seems to be reminiscent of a similar story that Cardi B. told in an Instagram Live from several years ago, back when she was still a dancer. In it, she described how customers would pressure her for sex at the club, and she would go back to hotels with them, drug them, and rob them. Earlier this year, the IG Live resurfaced, and some segments of the online sex work community – notably, mostly white or white passing strippers – condemned Cardi, often betraying an extreme lack of understanding or empathy for sex workers of color – particularly Black queer and trans sex workers – face on the job. Cardi cited her own limited options at the time as a way of explaining, though not excusing, her actions. While Ramona and Destiny were also navigating severely limited options after the 2008 economic crash, it can’t be understated that the situations they found themselves in were very much not the same. And while Destiny certainly contends with danger and even assault on the job – something that all strippers experience and have few to no protections around – much of their decision to drug and steal from men seems related to their distaste for the more physical elements of the job, and a sense of superiority over the workers who perform them.

This is reflected in perhaps the most egregious example of whorearchy stemming from the real story that Hustlers is based on. Samantha Barbash, the woman Ramona was based on, refused to take part in the movie, citing that she wasn’t offered enough money for her life rights to want to be involved. Instead, she’s writing a book of her time as a hustler, not an autobiography, but “a memoir that combines 50 Shades of Grey and Molly’s Game.” Several sites have reprinted an excerpt from her memoir in which she describes the specifics of the scam she and Keo ran together. In the excerpt she explains her own perpetuation of the whorearchy and how she took advantage of it, separating the women she worked with into “top dollar” girls with “perfect bodies and beautiful faces,” mid-tier “fluffers” who participated in some sex acts, and the “low tier” workers who offered full service. When asked if she had ever stripped, she claimed that being portrayed as a stripper in the movie was “defamation of character,” though since the movie release has trotted back this statement and claims to have stripped briefly before working as a hostess. Keo, the self-proclaimed “Sophisticated Hustler” is hardly better, describing to Pressler (whose language describing sex work in 2015 is also atrocious) in the original article how she and Samantha would get “the largest cut, with minor players getting increasingly minor sums.” That, my friends, is called trafficking, making Samantha and Roselyn pimps. They steal from rich white men, certainly, and you’ll never see me complain about that. But they harm other women to do it, to line their own pockets first and foremost. Rather than being a savvy indictment of capitalism, Ramona and Destiny (and Samantha and Roselyn) become the same type of entitled and violent abusers the movie shows them rebelling against.

I spoke to Karina Pascucci, who knew and worked with Barbash and Keo at the time of the scam ring. Pascucci, on whom the character of Annabelle (played by Lili Reinhart) is based, corroborated the attitudes that Barbash describes in her memoir, and Keo shamelessly espouses in her interview with Pressler in 2015. “Samantha would hold pay over [me] and someone else so we couldn’t ever really leave because her and Rosie needed us the most. They always knew what they were doing…when you’re out for blood, it’s obvious. Working with them was definitely manipulative and controlling. We didn’t work together, it was more them working against us. Using and manipulating people isn’t a hustle, it’s harmful, and too many people got hurt in the process.” Pascucci, who in the aftermath of the movie is curating a blog of untold stories of survivors of violence, said of Hustlers, “I was not happy when I heard this was first happening. It tore me up. I’m not sure if this movie did more harm than good.”

Seeing the movie with all of my coworkers was an incredible experience – though not because of the movie itself. I loved being out in public, loud and proud and joyful, with a dozen of my coworkers, hollering and heckling at the screen, stomping around proudly afterwards, an unconquerable ambush of strippers getting men to buy us celebratory shots and abandoning them as soon as the money stopped flowing, beholden to no one, owing no man a single thing, least of all our attention. Yet the more I learn about the truth that Hustlers is based on, the less I feel it accurately reflects what it is like to be a stripper, and the more concerned I become regarding the impact it may have on the industry I will be a part of for the foreseeable future. Some of my coworkers have said the same. Last night at the end of a painfully slow shift, one of the women I work with said of the movie, “I hated it. I felt like they just made shit up. Our lives aren’t like that.” Another said, “It was fun, I guess, but they glamorized a lot, and most of it didn’t feel like my life.” That’s because most of us don’t live in penthouse apartments in Manhattan, drive Escalades, or commit hundreds of thousands of dollars of credit card fraud. There’s nothing wrong with preferring the finer things in life, but most sex workers I know – whether we’re strippers or full service workers – are just regular people, and post SESTA/FOSTA, many of us are struggling to get by. We work to pay our rent and student loans, or to support our children and families, doing an honest night’s work that has always been stigmatized simply because it involves our bodies and sex, or the suggestion of it.

The fall out of the movie has similarly been quick and harsh: in response to the #TweetYourHustle marketing strategy that was rolled out in the days before the movie release, sex workers astutely pointed out that tweeting our hustle is a great way to get banned or shadowbanned”from the very platforms we depend on to survive. While this is something sex workers have always been at risk of on social media, and are at increased risk of post-SESTA/FOSTA, the irony of the marketing around a movie ostensibly written for sex workers actually harming sex workers is just another demonstration of the unintended consequences that arise when non-sex workers try to tell (and profit off of) our stories. Indeed, in the aftermath of the marketing campaign, Twitter – one of the last social media platforms where sex workers can promote their content online – has been attempting to verify sex worker accounts and demanding sex workers’ phone numbers.

![@YEVG3NIYA: This is precisely why sex workers don't like when stories about us are done by those are aren't us. We wind up getting shitty takes like this [Quoted tweet, from Amanda Mull: My review of Hustlers is that I too would like Jennifer Lopez to invite me into her giant fur coat and teach me how to do credit card fraud]](https://www.autostraddle.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/yevgeniya-bad-takes.png?resize=590%2C413)

Nothing encapsulates for me the frustration I feel around Hustlers, and non-sex workers playing with our lives in the name of their art, more than this quote from Constance Wu: “I didn’t want to do nudity. I just wasn’t into it. It’s not that I think there’s anything wrong with it, and I don’t believe in it. It’s just a personal thing.” Everyone is entitled to their boundaries, of course, but the irony of this statement is impossible to miss. If you can’t handle the titties, get out the strip club, babe. Even if it’s a fictional one.

Ultimately I don’t believe that even in trying to create a movie for us, Scarafia and her team truly put their money where their mouth was in terms of helping the sex work community. Maybe that wasn’t their job, or even their intention. But when it comes to sex workers, I’m not super interested in representation, especially not the kind of representation in Hustlers. To me, it feels as empty as when, in the beginning of my writing career, editors would approach me to write for “exposure.” I don’t need exposure, I need results. And I need to pay my damn bills. As one sex worker, Jenda Neutral, a trans sex worker who worked hard to raise awareness of Barbash and Keo as sex traffickers, and had many of their posts deleted from Instagram for their efforts, said, “I don’t respect the movie itself, just the conversations it brought to light.” Of the real life so-called “hustlers,” Barbash and Keo, Jenda Neutral continued: “They are advertising their books to the sex worker community, particularly to strippers & prostitutes, as well as referencing the movie. I was livid.” And with good reason, as Barbash and Keo’s books, and to a lesser extent the movie itself, largely involves non-sex workers profiting off of sex worker stories and even the actual harm of sex workers themselves. “I need to let sex workers know these women are not allies and they are openly stigmatizing sex workers & sex work while once again profiting from the community,” Jenda Neutral told me.

So the movie debuted, and probably some of you are rushing to your local pole studio now or ordering your first pair of Pleasers to learn how to be fly like us. While you’re doing that, ask yourself what you’re doing to prove that you not only enjoy consuming stories about us, but can also step up and help protect, respect, and honor us as well. For me, an IRL stripper, Hustlers was fun only in as much as being around a group of buoyant, unashamed sex workers is one of the best gifts I’ve ever given myself in my life. And unsurprisingly, I vastly enjoy being a sex worker more than I enjoy watching a movie supposedly about us written by someone who is not one of us.

Thank you for this, Janis.

It’s really powerful. Thank you for letting us into your world a little. <3

Ohhh shit, this was good to read. I still haven’t seen the movie- I’m looking like the pupa stage after surgery and don’t want to leave the house- but I was excited to see it. I’m sure I will when the swelling goes down, but the extra backstory on the creators, sources, and extras wasn’t stuff I’d heard. Not at all shocking, but I guess I thought there was more community involvement then there was. I haven’t worked at a club in 15?? years, barring that one time, but I still have friends that dance and they deserve way better than to be treated like this.

Wow thank you for sharing your experience. I was curious what the movie was all about and I’m so glad to hear about it from an informed source!

Thank you for this thoughtful piece. The sex worker perspective is obviously needed here. Grateful to autostraddle for publishing this. Definitely a different take than Carmen’s much more positive one last week. Gave me a lot to think about and hearing more sex worker perspectives within your writing (as well as your own perspective) is definitely making me reevaluate my initial impressions. Not yet seen the movie, and now not so sure I will

Thank you so much for writing this! It was really informative and eye-opening for me.

echoing the gratitude here 💕thank you so much Janis for writing this, and taking the time to educate and share your experiences with us.

Well written and insightful. I’ve yet to see the film, but have read the original article it’s based on and this makes a great addendum.