How long has it been since someone last touched you?

If you’re quarantining alone in the time of coronavirus, that question might be a painful one to try to answer – or even to think about. As a practicing therapist in New York City, isolating in Queens – the epicenter of the epicenter of the virus – I have a handful of clients on my caseload who are quarantining alone or with relative strangers for roommates. While quarantine and social distancing measures aren’t fun for anyone, early on I found myself thinking about my clients who are quarantining alone more than I usually do in between sessions. This didn’t surprise me – after all, solitary confinement is considered by many to be tantamount to torture, despite its abysmal pervasiveness in the United States. And while voluntarily quarantining in the midst of a pandemic should by no means be conflated with state sanctioned brutality, our bodies may still respond to long term and indefinite solitary living (and increased and chronic anxiety and stress due to the collective trauma of COVID19) in similar ways.

Chances are, you know someone who is quarantining alone right now. Maybe even you, yourself, are alone, and have been for the past several weeks. If so, it’s important to learn how this extraordinary circumstance might be effecting your mental, emotional, and physical health – and what steps you can take to mitigate and reduce that harm.

Basic Needs

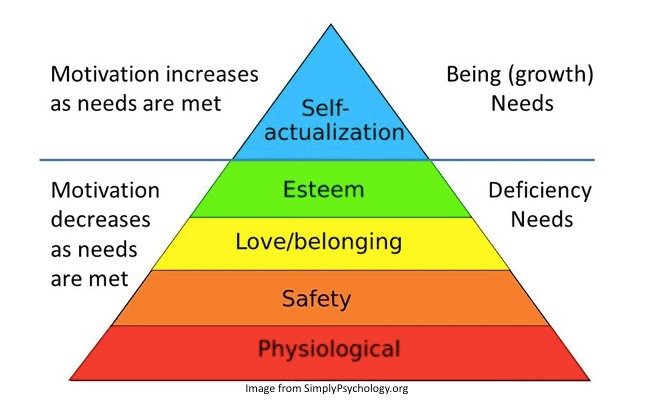

When we think of our basic needs, a few obvious things come to mind: shelter, food, and running water are usually the first things we name. On what’s known as Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, they make up the base of the pyramid of physical safety requirements. Moving up the pyramid (pictured below) you’ll see things like safety and security; “belonging and love needs” which we find in family, friendship, and intimate relationships; esteem needs (relating to how we feel about ourselves and our sense of accomplishment), and finally, our need for self-actualization, or the sense that we are living our lives to our fullest potential.

The needs listed on Maslow’s pyramid are split into two categories: deficiency needs (needs that arise due to deprivation), and growth needs (needs that we have to fulfill in order to self-actualize.) The difference between them is that when a ‘deficiency need’ is more or less sated, it tends to go away (for example: You’re hungry, you eat an entire giant bowl of popcorn Olivia Pope style, and you’re sated and able to continue going about your day as a HBIC.) Growth needs, by contrast, continue to be felt and are motivated by our desire to grow. When we get to a point where we are “reasonably satisfied” by our level of growth, we might call ourselves self-actualized – though this is something that can be fairly ephemeral.

The relationship between deficiency needs and growth needs is important, specifically because difficulty meeting our deficiency needs – food, shelter, safety; safe and affirming relationships; and esteem for ourselves – can also make it difficult for us to reach the top of the pyramid.

Maslow, according to Simply Psychology, did include sex within the bottom tier of physiological needs (and, oddly, included “sex” before “safety” needs, and separate from needs for love and belonging). Nowhere on the list, though, is any acknowledgement given to human need for touch as something separately, though related, to sex.

Reluctance to separate sex and touch in the mainstream is unsurprising to me, given the observations I’ve made over the past several years that I’ve worked as a sex educator – it’s not uncommon, especially in mainstream culture, for us to assume that our needs for intimacy can only be met in romantic or sexual relationships, and those relationships are usually depicted as heterosexual relationships between no more than two cisgender people. In queer spaces, of course, there’s more room to challenge that, and more and more conversations are taking place about the importance of platonic intimacy, romantic friendships, non-monogamy, chosen family, and the myriad of other ways and opportunities we can create to satisfy our need for love and belonging. A few months ago, I wrote about the ways in which, within the queer community particularly, we’re forming new understandings and methods of slaking our skin hunger: allowing for physical intimacy to show up in platonic relationships, and undertaking a process of unlearning often gendered expectations in order to create new and more expansive meanings of touch that fit the shape of each unique relationship.

Touch – whether within the context of a sexual or romantic relationship or not – is a profound need for mammals, including and perhaps especially human beings, who have to navigate sex stigma and social constructs when attempting to meet that need. The confusing space that touch occupies in our lives has roots that stretch far beyond the lessons we learned about it in our own lives, however. The wounds we carry with regard to how we understand and ask for touch are generations-long, and vary depending on the assorted intersections of one’s identity. In Boundaries of Touch: Parenting and Adult-Child Intimacy, Jean O’Malley Halley traces the lineage of touch, particularly within Western culture in the past two hundred years. With deftness, she illustrates the racist, femmephobic, and homophobic roots of our touch-averse culture, describing how behaviorist and child development theorist John Watson emphasized a method of childrearing that disavowed almost all touch between parents and children, conflating it with the racialized “lower class” patterns of raising children with touch and affection. Touching a child too much – hugging, cuddling, soothing a child when they’re hurt or scared – would, according to Watson, actually harm the child more than help them, leading to weak or effeminate adults (to be clear: Watson was mainly concerned with the men said children would become) who would stray too far from the (straight, white, upper class) rational (rather than emotional) Enlightenment Ideal.

Dr. Spock, the child psychologist who came on the heels of Watson, did much to correct this with his emphasis on attachment parenting, though he, too, was mainly teaching for an audience of wealthy white women who were expected and could afford to stay home all day with their babies strapped to them. That this was an ideal inaccessible to many, however, didn’t change the fact that women’s inability to meet it was often responded to with shame and blame. An understanding of both Watson and Spock, though, demonstrates how our conceptualizations of touch begin far earlier in our lives than the point at which we reach sexual maturity. The impact of lack of touch, too, is felt much earlier – with minimal touch correlated with cognitive delays, anxiety, and emotional distress infants – while the benefits of touch are clearly documented as a “protective layer against stress,” releasing oxytocin (a bonding hormone) and decreasing blood pressure.

Still, if your social media feed looks anything like mine, it’s often full of folks talking about the impact that COVID-19 has had on their sex and dating lives: promising relationships that may have just started being interrupted right in the middle of the most intense part of New Relationship Energy; the awkwardness and potential superfluousness of Tinder; weighing the pros and cons of moving in with a partner right now, especially if it wasn’t something you were planning to do for another couple of months; jokes about vibrators needing a break and a glass of water from all the overuse they’ve been getting lately.

And while our relationship to our sexual and erotic lives is certainly undergoing a dramatic shift right now, sometimes I wonder just how much of this is purely about sex, or whether or not it’s also – and perhaps more – about loneliness and lack of touch. SX NOIR, of Thot Leader Podcast, spoke to this in a recent Instagram post about her experience twenty-six days into quarantine and social distancing while single. “I have been quarantining alone and it’s very difficult but I am a very touchy person and in my job I’m constantly communicating and interacting and touching and being with people in person,” she said. When I reached out and asked her if she would explore this with me further, she compared the jarring feeling she gets post-digital interaction to the drop sometimes experienced after masturbating: “You have this dopamine release when you masturbate, right, it’s this pleasurable release. And then its kind of over, and it’s a deep fall back to the real world, back to this isolated alone feeling, because you don’t have the option of going out into the world and being around people.”

The Body Online

That jarring navigation of both digital and physical space is something that I’m hearing from a lot of my clients – particularly those who have experienced trauma, and for whom a tendency to dissociate in times of stress or danger has become second nature. For some, it’s even experienced as a kind of dysphoria. Unfortunately, given the nature of these particular circumstances, dissociation – a hallmark of the freeze response within fight, flight, and freeze – it’s a behavioral pattern that more and more people are likely to be experiencing right now. You can’t fight a pandemic – not in any way our bodies will readily recognize as fighting – no matter how much war rhetoric is used by politicians and mainstream media as they report about the coronavirus. And sheltering-in-place is, in its very definition, the opposite of “flight.” As time goes on, and as quarantine continues, the circumstances under which we are struggling to live our lives and recreate some sense of normalcy lend themselves specifically to our “freeze” responses.

When my clients first started describing this to me, I found myself thinking of my own experiences with Zoom sessions with my family, from whom I am quarantining separately (but not alone), though we only live twenty minutes away from each other. In one Zoom call, the gang was all there: Mom, Dad, my little brother, even my dog – perhaps the member of the family most difficult to be away from right now, given how much our relationship is (obviously) based entirely on non-verbal communication and touch in order to convey playfulness, affection, and love, as well as the history of my relationship with her: I adopted her and raised her during an incredibly emotionally difficult time in my twenties, connecting with her when it was hard for me to connect with anyone at all. While ostensibly, we “saved” her when we took her in, my mom is quick to point out that she “saved us right back.”

As I cooed at my dog and called her name on our Zoom call, I also noticed the impact this medium had on her. It was clear she could hear me, and even that she could recognize my voice: She tilted her little graying head to the side, pricked up her giant chihuahua ears, and tentatively sniffed at the screen, or else turned toward the door, or toward my mom, confused. My voice was there, but I wasn’t. It didn’t make sense.

Dogs, of course, have the luxury of not pondering the somatic implications of this, so soon she settled down and didn’t let my voice springing up from the iPad, or the question of why the rest of the pack had focused all their attention on a small silver rectangle, bother her. But I’ve come back to the image of her, bewildered, time and time again as I talk to my clients about what it is like to be relying solely on platforms like Zoom and FaceTime for all of our social interactions.

Sx Noir agreed with me: “With quarantining, it’s jarring to go from being completely alone, to being with just about anyone. When you’re alone, your body reacts differently than when you’re with other people. Your body reacts differently, your behaviors are different,” she told me. “But the mind doesn’t register video the same way it does in person. I notice when I finish a video chat it can be intense. We live intersectional lives – for example I can have a video chat about Survived and Punished – or it could be just me hanging out with my friends from high school.” Regardless of the content of the video chat, though, ending the call tends to have a similar effect: “You’re completely alone and the world is echoing around you.”

Moving Toward Embodiment

How, then, can we fill up that empty space of alone-ness and interact with those echoes intentionally? Some folks I’ve spoken to about this describe a feeling of “dropping” back into their bodies after ending a video call, realizing with a jolt where they are, and that the person they were just talking to is blocks – or miles, or entire timezones – away. In one such instance, I wondered aloud to a client what it might be like for them to get up and walk through the threshold of their bedroom, creating the sensation, perhaps, have just getting back in from talking to their friend. It was not so much “tricking” their body as being curious and experimental about how they might regulate and work with the information it was processing by being forced to do all their relational work with screens rather than in person.

Movement, after all, is one of the best ways we can engage intentionally with our stress response, though I say this of course with the caveat that movement can be a tricky thing for folks for multiple reasons: movement often seems to be shorthand for “exercise,” a loaded topic in a fatphobic and bodyshaming world. Movement, also, seems to presume a certain level of able-bodiedness that can be inaccessible for those who struggle with chronic pain and illness or mobility issues.

And yet, as Emily and Amelia Nagoski write in Burnout: The Secret to Unlocking the Stress Cycle, a movement practice can be eminently accessible. It’s not about running marathons or lifting weights. Rather, it’s about an intentional engagement with our bodies: curiosity about what stress feels like in our bodies, how we are physically changing, even on the most minute levels, to accommodate this stress, and willingness to experiment with different ways of shaping, shifting, or releasing it. (This awareness, by the way, is called interoception, and it’s a way of knowing that often we’re too busy and scattered to cultivate. Add trauma into the mix, and the idea of familiarizing ourselves with the intimate and minute sensations of our bodies can even be frightening – so it’s okay to take it slow.) Even laying still, without moving perceptibly, and holding tension in our muscles for ten seconds and then releasing, can be a way of engaging and closing the stress cycle.

And there’s no wrong way to do it – or a limit to the ways you can engage all of your senses in moving towards embodiment. “One of the things that I’ve been doing that’s helped me a lot is using music to help me come in and out of different situations. So if I have a Zoom call that’s really intense, I will just play some piano music some classical music. Or maybe Megan Thee Stallion, or whatever I need in that situation to just move with the music and come back into my body and feel my body feel vibrated by the sound,” Sx Noir said. “I’ve been loving throwbacks like Donna Summer and her disco jams and just kind of like realizing that my body does move, I am a person, I am here in this world, and that’s really been helping.”

While intentional movement can help us navigate the increase of online-ness in our lives right now, however, it doesn’t solve the question of skin or touch hunger, and the fact that many folks are going on a month now of not being held. To grapple with this, and to be mindful of the ways in which long term isolation can be experienced as a form of trauma, I turned to The Body Keeps the Score, perhaps the definitive book on trauma and somatics. I was reminded of how, when trauma survivors were studied with positron emission tomography (PET scans), imagery of their brains while describing trauma lit up as if the trauma were actually happening.

I wondered if the opposite – imagining touch and having the brain respond as if we are actually being touched – might also be possible. Our brains are powerful things, after all. It certainly seems possible about sex: Some people report that they’re able to think themselves into orgasm –look, Ma, no hands! – enough so that a group of researchers at Rutgers University actually studied it and concluded that, “On this basis we state that physical genital stimulation is evidently not necessary to produce a state that is reported to be an orgasm and that a reassessment of the nature of orgasm is warranted.”

(It’s unclear to me how much of that reassessment was actually done, and I haven’t been able to find any research on whether or not imagining touch causes the brain to respond as though we’re actually physically being touched IRL. But I do know that our imaginations are powerful, and that we always have the opportunity to engage with our imaginations – perhaps now, in this moment, more than ever before.)

Sex educator Corinne Kai also emphasizes the importance of patience, curiosity, and a trust in our own resilience when it comes to skin hunger. In an recent article for Allure, they encourage creativity with regard to cultivating solo intimacy: “Some types of solo intimacy could be giving yourself a hug, self-massage, cuddling your pets or a stuffed animal/soft pillow, taking a long bath or shower, swaddling yourself in a blanket, masturbating, playing with textures like feathers or silk or leather against your skin, and slathering yourself in lotion,” they write. The key is to strive to be as present with yourself throughout the process as possible – even if part of what you’re being present for is a keen awareness of your own loneliness, tenderness, or grief.

Finally, if it’s specifically sexual/romantic touch you’re missing, perhaps a reframe of this particular experience of isolation will help. In Pleasure Activism, adrienne maree brown devotes a chapter to the concept of strategic celibacy. For those who are quarantining alone, perhaps celibacy feels more grudging than strategic, but perhaps the opportunity still stands “to decolonize [our] longings and remember [our] sacred sexual self.” brown lists several reflective questions in her chapter on strategic celibacy that can also be considered in the context of skin/touch hunger: “What are you focused on? What do you see, hear, or otherwise sense that makes you feel flushed and quick? What produces a physical response of desire?” With regard to touch, what comes up when you think about touch? A particular person? A style of touch? Do you want to be held, full body against full body? Do you want a massage? What would it be like to massage yourself: your palms, your feet, your forearms, your scalp? Do you want someone to play with your hair? Do you want to shower with someone? Do you feel affectionate? Do you feel longing? Let your mind wander, and notice what sensations arise in your body as you do. And, as always, be gentle with yourself. As adrienne maree brown writes, “This is a time for curiosity, not judgment. Be tender with yourself, tender with your history.”

I wish I could end this essay with more concrete advice for easing our skin hunger, but as long as we’re social distancing for our collective safety, I can’t. I can only affirm for you that your desire to be touched, to be physically among other people, is a natural, legitimate need. This longing is a desire that has evolved within you in order for you to survive; this is why isolation is so hard for us. When clients tell me they met up with someone, even briefly, I don’t judge them. How could I? Instead, we talk about harm reduction practices, and doing the best they possibly can. And while I can’t tell you how long we’ll need to be socializing only online – apart, together, but still so very apart – I let you know that I have so much unwavering faith in all the power and potential of your imagination, your creativity, your fantasies, and your dreaming.

Great article. Would have appreciated inclusion of a disabled perspective in this. It’s been longer than a month for some of us… years even. There are some great suggestions in here I am going to try.

Agreed. It has been about 3 years for me.

Thank you for this, quite a few concrete things I’m going to try!

I really appreciate the “imagining touch and having the brain respond as if we are actually being touched – might also be possible” part, because this has been my main method of coping with isolation/lack of touch. The last touch I shared was thankfully with my somatic therapist, which is always a very healing and safe touch and bodywork. I’m extremely grateful to be able to work with her generally, but even more right now! She’s been doing video sessions, some 1-on-1, which is great, and also some larger group resiliency calls, for both she talks through kind of visualizing the usual bodywork we would do in person. It absolutely has a real physical impact and is very soothing! I can imagine a fair amount of the usual experience. It definitely isn’t the same and sometime has that post-drop, but that imagination work is really powerful!

*affecting, not effecting (“how this extraordinary circumstance might be effecting your mental, emotional, and physical health”). Sorry to be That Person but that particular one is a pet peeve!!

thank you so much for this! as a trauma haver who is quarantining alone while recovering from a big breakup, i feel all this really hard, and am sending warmth to everyone else who’s going through the same kind of thing.

i am also a trauma haver quarantining alone while recovering from a big breakup. it’s quite brutal. solidarity. <3

[cw for mention of suicide & psych hospitalization]

I appreciate you writing this up.

I want to add/emphasize that paying attention to one’s body or breath can be extremely triggering and dangerous for traumatized people, and it’s okay if those types of exercises don’t work for you. See Clementine Morrigan’s work and Instagram for more on that.

Also, thank you for not judging isolated people who meet up with other people. Folks who are new to quarantined life will likely learn that mental health issues get more and more intense and desperate the longer you are in isolation. I once went 11 months without a hug and I nearly died, no exaggeration. Getting COVID-19 is awful. AND, people dying of suicide or having to be hospitalized with mental health issues due to isolation is awful too (and hospitalization exposes folks to coronavirus). Harm reduction is key here. Even meeting up with a friend for one hug (while wearing masks and goggles and washing hands a lot before and after) can be hugely beneficial.

I agree so much about harm reduction.

And thank you for the recommendation of Morrigan’s work, I’ll definitely be checking that out!

“Getting COVID-19 is awful. AND, people dying of suicide or having to be hospitalized with mental health issues due to isolation is awful too (and hospitalization exposes folks to coronavirus). Harm reduction is key here.”

I have been thinking so much about this. I’m currently fortunate to be quarantined with my wife, but have experienced very long stretches of isolation through periods of trauma and mental distress in the past, and even as someone who can normally cope pretty well with solitude, it was horrendously difficult during those times. I wish there was a way to get the message out that if people are *truly desperate and in despair* it is ok for them to seek out comfort and touch as safely as possible, without weakening the important message to the general public that distancing is still necessary whenever possible.

Thank you for writing this. While dealing with anxiety today while also stuck in bed due to chronic pain, I experimented a bit with just moving my fingers in different ways. Hard to tell whether it released physiological stress, but it did make me feel a little less helpless and a little more like I could at least try something out to care for my body.

As corny as it seems, reframing exercise as body movement has been helpful for me. I’ve started doing Joyn (joyn.co) which has these fat-positive, inclusive, and accessible body movement videos. Right now they have 30 free videos available and a free trial as well. I mostly hate moving but the videos are pretty cute and doable.