Welcome to Autostraddle’s APIA Heritage Month Series, about carrying our cultures from past to future.

If you polled Cecilia Chung’s friends and acquaintances about her best qualities, you’d find that “hilarious” is in the top two. When I think of her now, as I sit 3,000 miles away in Brooklyn, I hear her signature chuckle—her body leaning backwards, her glasses falling just slightly down her face.

Behind that laugh lies many years of struggle. While she was figuring out how to survive, she was also laying the foundation of movements for justice today.

Prior to arriving in San Francisco, the city she has called home for over three decades, Cecilia grew up in Hong Kong. Her early memories of childhood already demonstrated her divine feminine energy. She grew up obsessed with the stories of goddesses, especially Quan Yin, a Buddhist deity that reincarnated many times in multiple genders. Since her parents were rarely home during the day, she had the space to play with gender in skits with her sister. “I always played a goddess. And in primary school, I played a belly dancer when I was in the sixth grade.”

But the older she got, the more she felt the need to hide her femininity. She was already dealing with racist harassment at her boarding school. “They called me ‘slant eyes’ and ‘socket face.’ I didn’t want to give them more ammunition.”

She didn’t allow the goddess side of her to return until she started going to clubs in Hong Kong. During this period in the 80s, artists like Prince and David Bowie wielded androgyny against the strict rules of gender. But they were certainly not the only ones. Gender variance is well-documented among Indigenous societies globally, but that history is often buried by colonizing governments. In fact, many people who are called “trans” today were sacred people — shamans, priests, mediums.

As if she were channeling Quan Yin, Cecilia dolled herself up for club nights. These instances helped ease her way into a gender transition, which began on the other side of the world. Her family moved to the United States in 1984. And her life continued to vacillate: role play then boarding school, club nights then college. When Cecilia began her undergraduate studies in San Francisco in 1985, she knew she was through with hiding.

![]()

Transitioning can mean entering a new sense of self. It can also be the result of finally letting our inner child have the freedom we’ve always craved. While trans people get closer to who we are, our loved ones often position themselves further away from us. Cecilia became estranged from her family when she told them of her transition.

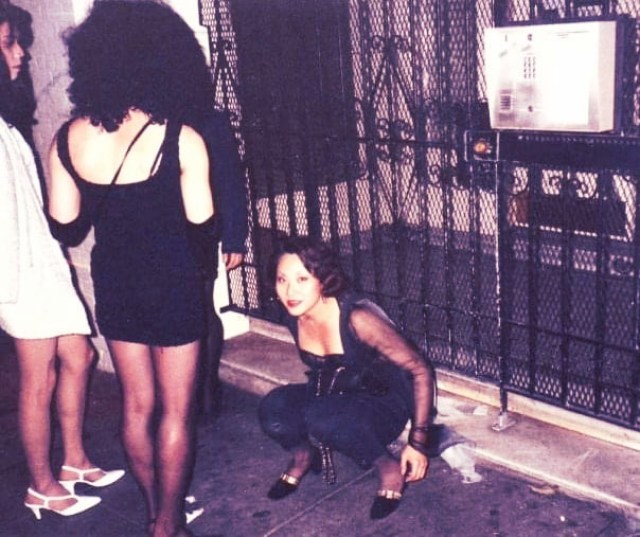

At the time, she had two jobs: at a finance company with a six-figure salary and as a language interpreter within the court system. She resigned from her finance job because she could no longer withstand the 16-hour workdays. She thought she always had security with her second source of income. But court judges took note of her physical changes due to hormone therapy and her contract was subsequently terminated. Without the support of her family and no way of supporting herself, Cecilia turned to the streets. She was a sex worker at a time when there were no digital mechanisms for screening clients to evade dangerous men, including the police. While she was homeless, she also self-medicated. That same year, she discovered she was HIV-positive.

Cecilia in 1993, the year she became homeless.

Her life was filled with loss: starting with the loss of her family and her career. And now, she was witnessing her community being taken by a mysterious virus. “I remember some of the girls. You’d see them one week. And the next week, they passed away.”

She experienced sexual violence during her time as a sex worker. Almost three years into her homelessness, two men tried to sexually assault her. She screamed for help and ran around their red four-seater, even jumping onto the roof of the car to be out of their reach. One of the assailants pulled out a knife and lunged at her. She tried to block the knife with her right arm and sustained a stab wound. When she eventually passed out from rapid blood loss, the two men kicked her until they heard sirens in the distance.

She was rushed to the emergency room with a punctured artery, a severed tendon, and nerve damage. When the nurse asked her for an emergency contact, she gave her mother’s phone number. Her mother arrived at the emergency room, finally realizing that her daughter’s transition wasn’t a temporary matter or a lifestyle. By then, Cecilia had already undergone years of trauma.

“How does it feel to retell that story today?” I ask her.

“It gets a little easier each time. But it’s taken a long time to come to terms with it. I felt like I was the criminal. They don’t see sex workers as human beings.” She was a target for rape and murder simply for being a trans sex worker. And she couldn’t turn to the police for any help. In fact, police officers regularly profiled and arrested trans women as sex workers and as “female impersonators.” These arrests would lead to the Compton Cafeteria riots and the Stonewall riots that launched a national LGBTQ movement. To this day, the police continue to attack and imprison trans women of color under the guise of enforcing the law.

![]()

After that assault, Cecilia channeled her trauma in the service of her communities — trans communities, people living with HIV, and sex workers. In fact, even while she was homeless she served on the San Francisco Transgender Discrimination Taskforce. She documented cases of discrimination against trans individuals, while experiencing them herself. She became a counselor for people who use drugs at Baker Places Rehabilitation Center and a counselor for people navigating HIV at UCSF Alliance Health Project. She dedicated herself to community work at a time when there were hardly any services being given to transgender communities, especially those who were migrants, sex workers, disabled, or living with HIV. There weren’t yet national organizations like Transgender Law Center, where she and I are colleagues, fighting legislation and shifting cultural perceptions of trans people. There weren’t progressive policymakers who fought alongside community organizers to decriminalize sex work. She playfully recounts, “We’ve been advocating for sex work decriminalization since the Jurassic period.”

Cecilia organized and spoke at the 40th anniversary event for the Compton Cafeteria riots, which helped launch a national LGBTQ movement.

Over the next two decades, Cecilia Chung would move through too many roles at too many organizations and governmental bodies to name. In 2004, she produced the first Trans March ever, which is still an annual event during Pride Month in June. She was appointed to Obama’s Presidential Advisory Council on HIV/AIDS in 2013. In 2017, her life’s story was created into a series by ABC called “When We Rise”; she was portrayed by the brilliant trans Filipina actress Ivory Aquino.

Her will to survive and help her community thrive has been recognized by the Levis Strauss & Co. Pioneer Award, the San Francisco AIDS Foundation Cleve Jones Award, the Human Rights Campaign Community Service Award, California Women of The Year, and the Out and Equal Champion of the Year Award, among others.

But perhaps the greatest praise she receives is from the people she calls family. She became a mother to so many. She became the mother who so many of us were denied. She became the mother who wouldn’t abandon us. She became the mother who saw our transness as something that made us even more deserving of her love. Her impact is felt in the hearts of every person who has shared stories and laughs with her.

As a daughter of Ms. Cecilia Chung myself, I indulge myself and ask, “What’s it like being a mother now? How does it feel to care for so many now?”

She spends a moment reflecting. “I never knew I would live this long. I thought I would die when I turned thirty. Ironically, that’s when I got stabbed in 1995. I would not wish what happened to me to happen to anybody else… My role is to be there and show them it’s possible to have unconditional love. And it’s kind of my own healing space. Because that’s what I wanted at the time.”

Like all mothers, Cecilia Chung was once only a daughter. She sought the same kind of love that her daughters find in her.

For a moment, I imagine the world she thought would be her reality, a world where she dies at thirty. I imagine myself as a motherless daughter, alongside her other children. I explain to her why I’m struggling to speak through tears, as she observes me on her screen. This very moment, a mother-daughter conversation, was something she was never able to experience as a young person. At least for a while, she, too, just wanted the unconditional love of a mother who understands. Now, she’s helping end the cycle of daughters who are broken by a world always at war with them. The same world that came close to killing her years ago.

Cecilia stands in front of the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial in Washington, D.C. in 2012. By this time, she had lived seventeen years past the age at which she expected to die.

This month, I implore you to celebrate the fact that you live in a world that’s been transformed by Cecilia Chung, alongside so many movement mothers. Mama CC helped set the stage for trans people to receive the proper resources in health, housing, and HIV care. She helped mold the landscape of individuals, organizations, and institutions that are making sure no trans person will go through what she went through. Her story has inspired the media and art that’s moved forward cultural ideas of who trans people can be.

The state of trans lives is nowhere near what it should be. But without Cecilia Chung and the ecosystem of leaders who each played their part in changing the world, we wouldn’t be where we are today. Today, as I sit safely in my apartment, with enough to eat and a network of people and resources to support me, I thank Mama CC and so many other trans elders. I have many trans siblings who don’t even have that much, who are without the basic means to survive. And that is why the work of trans liberation continues.

“There are others before me, too, who’ve been advocating hard, to make all this possible.” How fitting that in her closing words to me, Mama CC chooses to honor her own ancestors.

This is beautiful, Xoài, thank you.

I’ve looked up to Cecilia Chung for a long time. Thank you for this loving tribute and interview. <3

this is such a fantastic interview; I completely lost track of time while reading it, and am so grateful for what both of you brought to this conversation. thank you for sharing this!

Thank you for sharing.

Thank you for sharing some of Cecilia Chung’s story with us, and in doing so, for modeling some of the ways that we can honor our trans elders <3

Love this, thank you.

Thank you so much for this.