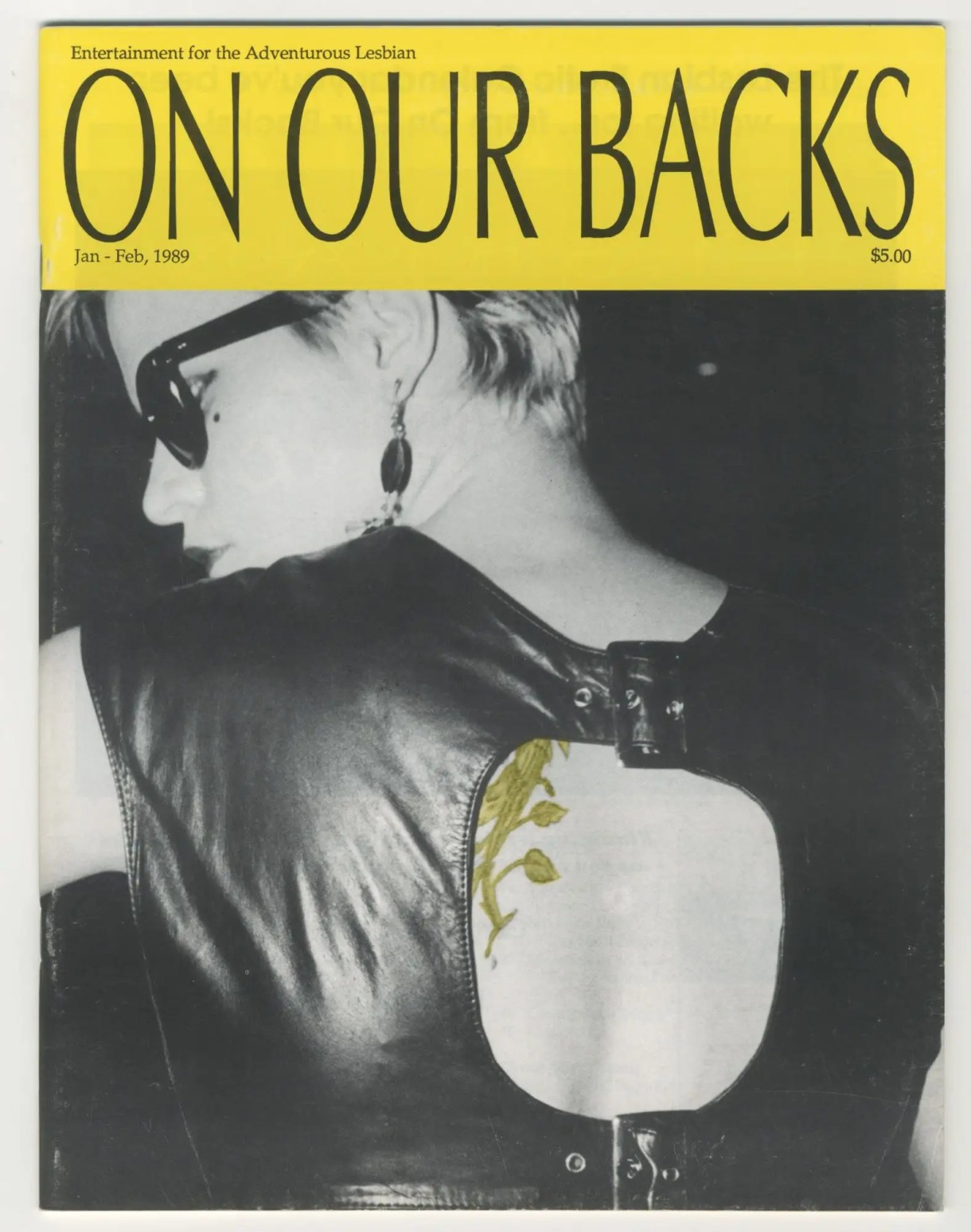

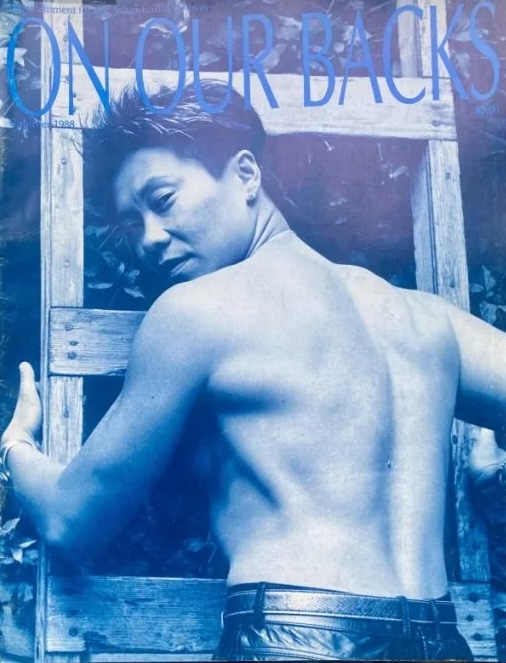

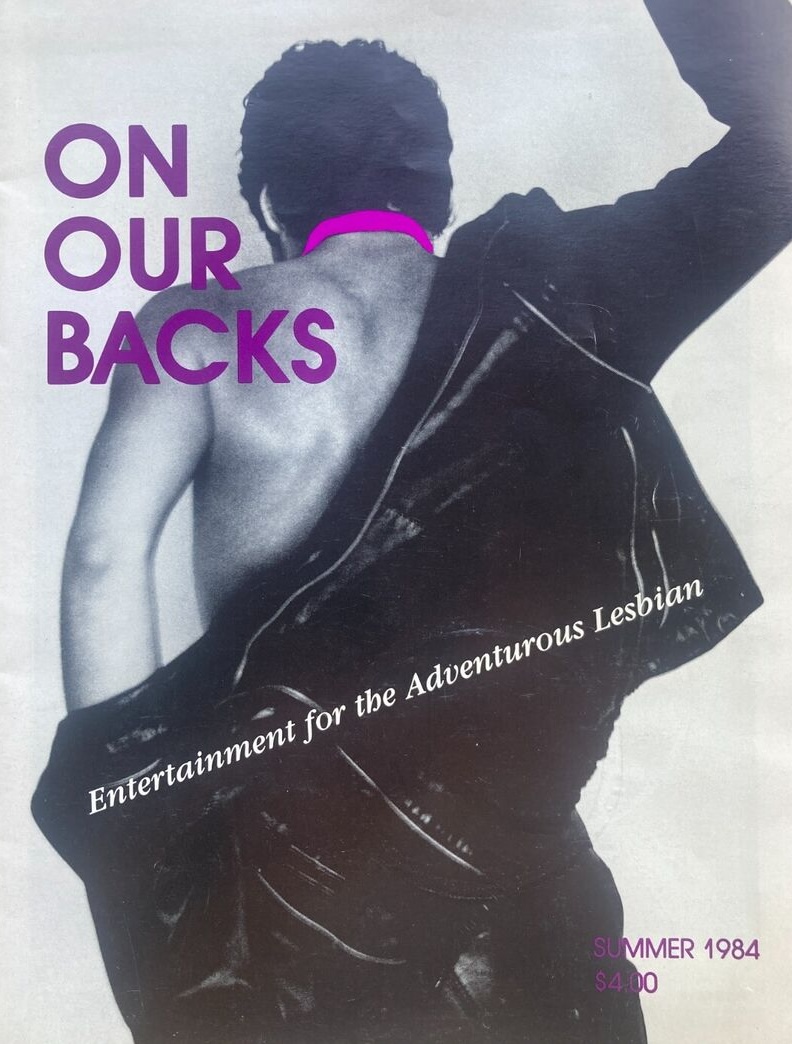

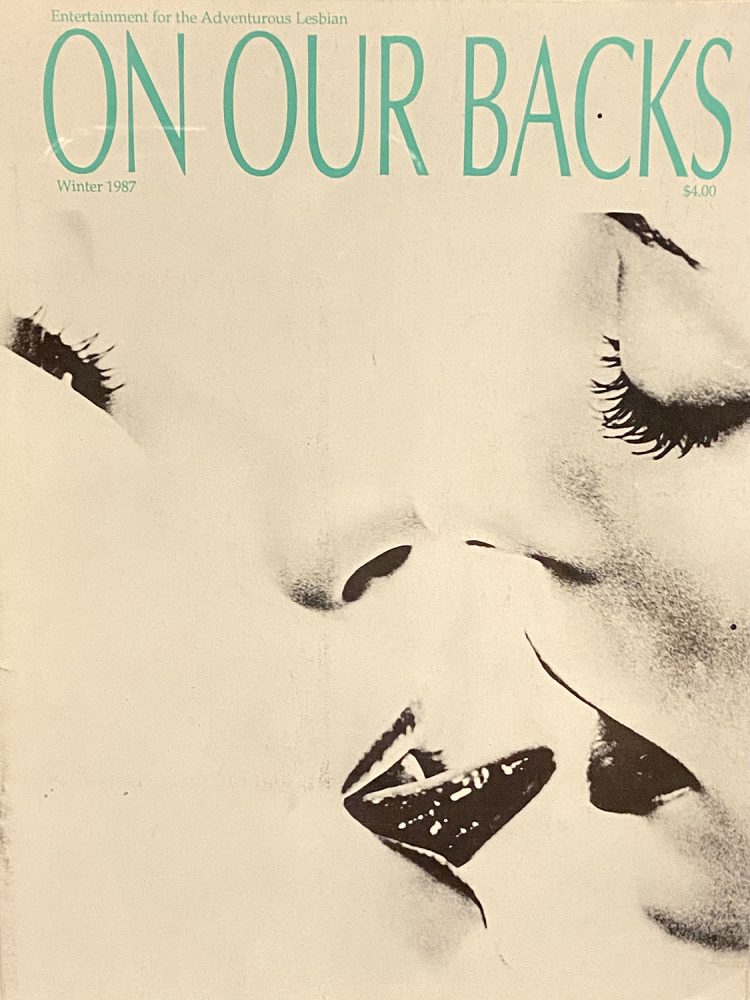

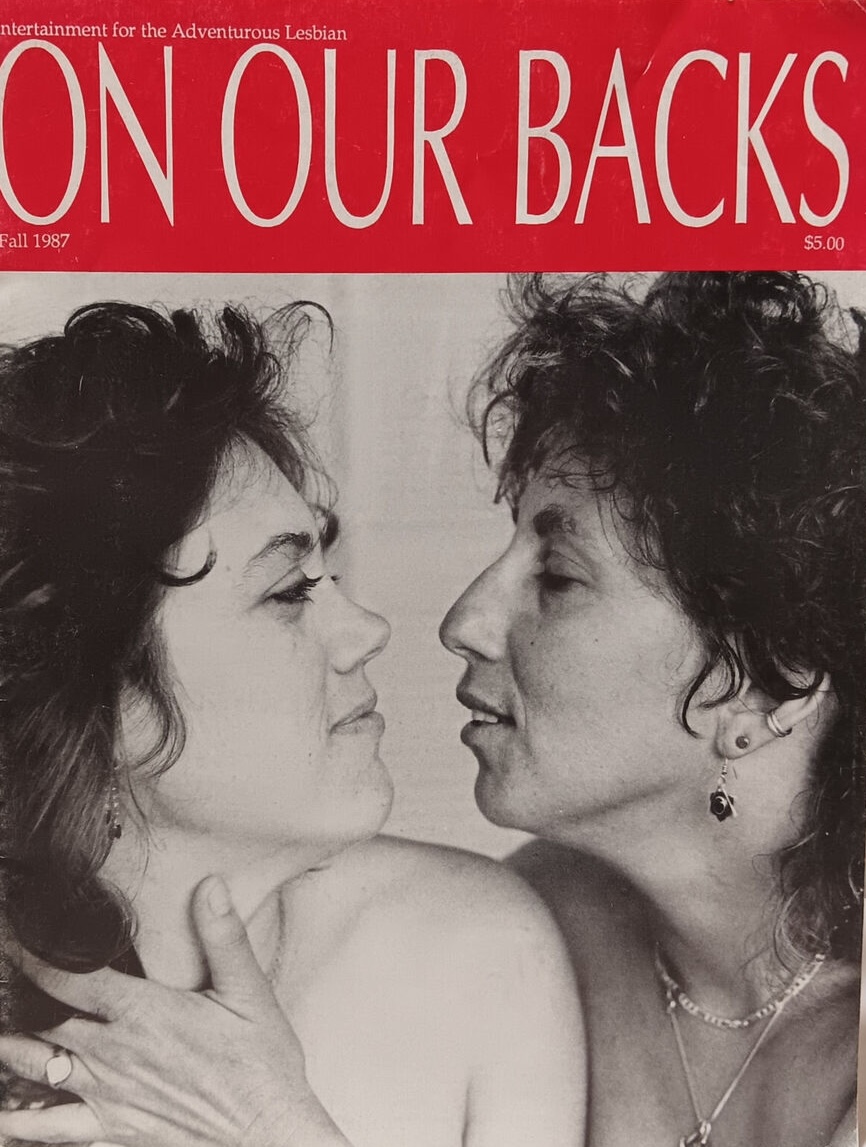

“It was one of those years,” says queer and feminist theorist Gayle Rubin of 1984. A “period of ferment over sex and feminist politics,” 1984 was a year of revolution, rebellion, and revitalization. It was also the inaugural year for the trailblazing lesbian erotica magazine On Our Backs.

Created by, for, and about lesbians, On Our Backs came about in the tumult of the “feminist sex wars,” a deeply polarizing internal debate in the feminist movement regarding sex, sexuality, pornography, erotica, and BDSM. Divided into sex-positive and anti-porn camps, the sex wars saw rabid disagreement on what the nature of things like pornography were doing for lesbians and for society as a whole. Many feminists argued that pornography and erotica were inherently objectifying and abusive. Writer and theorist Andrea Dworkin argued that not just pornography but heterosexual sex as a whole was a “means of physiologically making a woman inferior,” and claimed that anyone aroused by porn that depicted sexualized violence (whether real or scripted) “was evidence of a mind that’s absorbed the propaganda of the patriarchy and eroticized the subjugation of women.” On the flipside, sex-positive feminists argued that pornography itself was not an inherent evil, but rather its morality was dependent upon the creators and participants. Rubin, one of the founders of the lesbian feminist BDSM group Samois, believed sexual liberation was a key component of the feminist movement and that public expressions of female sexuality were crucial in asserting women’s existence as fully realized beings.

Both sides of this movement used media as a weapon to push their points across. off our backs, a radical feminist periodical first published in 1970, was created to discuss feminist lives and activism. However, several feminists believed the magazine’s take on sexuality to be “prudish” and its avoidance of properly addressing sexual liberation to be a huge oversight. Fourteen years later, in 1984, these feminists responded with On Our Backs.

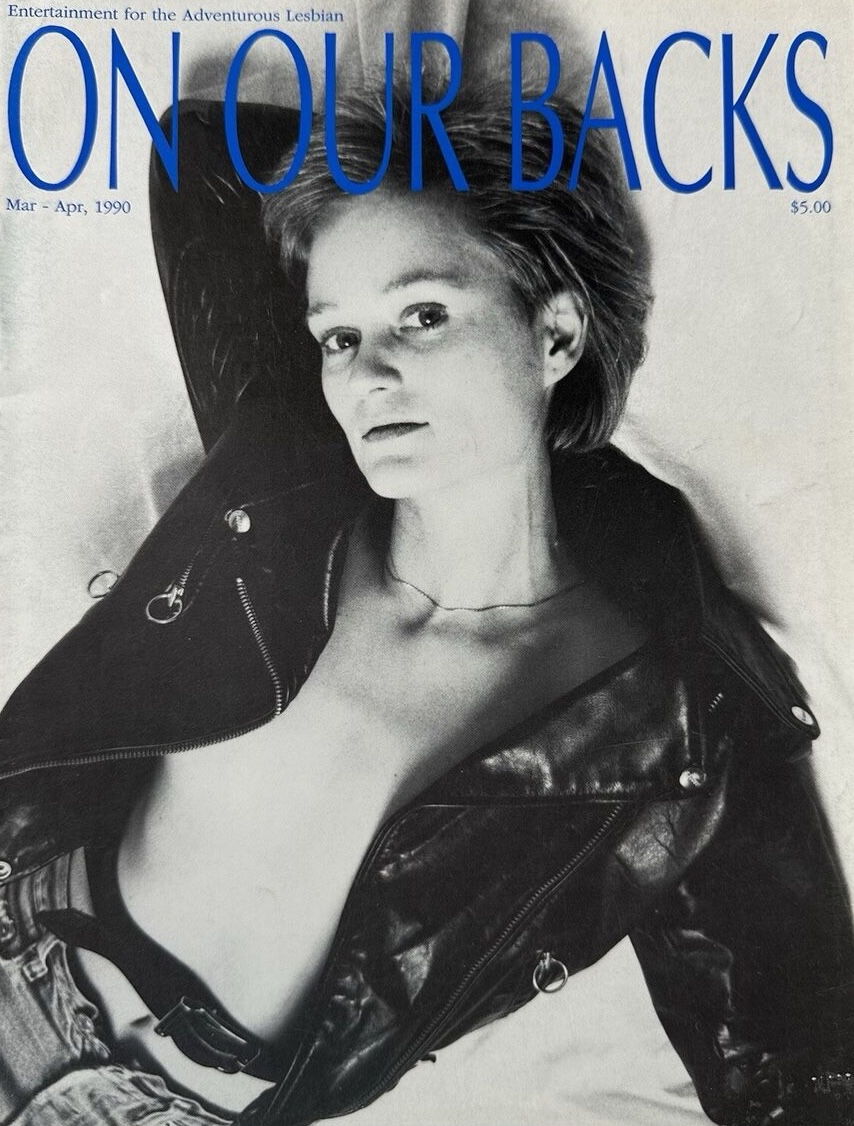

On Our Backs, which originally ran from 1984 to 1990 and was revitalized from 1998 to 2002, existed for one central purpose: to portray lesbian sex and sexuality, with real lesbians. By “real lesbians,” the magazine meant lesbians who allowed themselves to be photographed in expressions of sexuality that felt true to them. “There were those of us who were very skeptical about the anti-pornography movement in feminism,” Heather Findlay, who took over the publication of OOB in the late 90s, tells me. “We thought it was censorious and anti-sex.” Findlay recounts a college experience of hers, partially inspired by OOB’s activism, in which she and a friend protested Playboy’s presence on Brown’s campus with their own magazine, titled Positions:

“Every year Playboy published its Women of the Ivy League issue. And they would advertise in the local Brown newspaper called the Brown Daily Herald for models. So somehow we got advance wind of this and on the same day the ad came out for this in the Brown Daily Herald, we bought a quarter-page ad and put out the call for women and men to model for Positions. [My friend] identified as straight and I did as gay, and we were going to make what we would now call in today’s language a pansexual publication. It just caused a huge media explosion. It was headlining in newspapers all over the country, that ‘Brown students were putting up a porno magazine.’ I just thought that that was the most creative and the most celebratory way to respond to the ills of pornography — not to censor it but to do our own. And to do it better.”

“To do our own, and to do it better” could very well be considered the rallying cry of OOB (I’m also partial to “come one, come all”). The magazine began in San Francisco as the lovechild of two lovers and three friends: Debi Sundahl, Nan Kinney, and Myrna Elana. Susie Bright and her lover Honey Lee Cottrell were attached to the project as well and became pivotal cogs in the “lusty lesbian” machine as editor and photographer respectively. OOB entered into a long lineage of lesbian periodicals — other publications like the Daughters of Bilitis’ The Ladder, Jeanne Córdova’s Lesbian Tide, Lesbian Connection, Sinister Wisdom, and others had been publishing (and some shuttered) by the time OOB entered onto the scene. Sundahl, Kinney, Elana, Bright, and Cottrell were intimately familiar with such magazines and were ready to throw their proverbial hats in the ring.

The work in OOB could be called a cavalcade of words, but subtle would not be among them. The first ever issue, available in full online thanks to the non-profit Internet Archive, is enough to make most blush. (I learned quickly that certain articles are not meant to be researched in a public coffeeshop.) 1984 is described as the “Year of the Lustful Lesbian!” on the first few pages, and the content makes good on this promise, with short-form erotic fiction and poetry accompanied by lascivious illustrations; advertisements for sex toys and sexual health clinics; features like “April First, 1984: Satire: English S/M group meets Anti-Porn Crusaders” and “Lesbian Strippers: Erotic Dance Benefits for On Our Backs”; and classifieds, proclaiming “witch wants same,” “novice femme wants experienced single (butch?) top,” and other discreet-yet-detailed personals. If the creators of OOB wanted to fill the niche of hard lesbian sexuality literature, they’d done a bang-up job (pun intended). The issues that followed were full of the same, and often accompanied by names that now vibrate in the lesbian/queer and larger literary canon with great power: Dorothy Allison, Patrick Califa (whose work was in the first issue), Sapphire, Joan Nestle, Jewelle Gomez, Leslie Feinberg, Alison Bechdel, Lea Delaria, to name only a fraction.

But such self-expression didn’t come without complications. “The big deal wasn’t getting people to take their pants off, it was seeing their faces,” Susie Bright, co-founder and iconic lesbian writer also known as Susie Sexpert, said in 2011. In the beginning (and throughout), many if not most of the contributors were behind the scenes as well. Bright discusses the first issue’s centerfold featuring Cottrell, a “Bulldagger of the Season” meant to replicate Playboy’s “Playmate of the Month.” In the photo, Cottrell is “gnarly,” her “brushy, silver hair sticking straight up” in nothing but white underwear and an unbuttoned white men’s shirt. While some women reacted favorably (Bright fondly remembers a woman mailing a photo of her masturbating to the photo), the staff also received immense vitriol, letters calling butches “disgusting,” and others decrying the sexualization of women by women.

OOB faced several complications when it came to distribution due to these reactions — Bright says “if it weren’t for the gay men’s bookstores and commie bookstores,” the magazine’s life may have been much shorter. She remarked that while gay men posing for similar magazines were much more open about using their faces, names, and identifying facts, lesbians were much more hesitant. Many letters of criticism were received by the staff, asking why the magazine couldn’t feature women who were “bankers, librarians, someone who wears pantyhose,” instead of just “rock chicks and strippers” — but as Bright says, the staff wanted to feature such women. The women themselves were just much more hesitant to actually volunteer for their sensuality to be photographed and printed for the masses. Likewise, the big ask of contributors and models to be “out” prevented involvement. But for many lesbians, OOB provided a relief.

“In those days, many of us queer women identified as either an OOB lesbian or an off our backs lesbian,” says Findlay. “To know that I could be gay and that I could be fully sexual and that I could define that the way that I wanted to, and that I could be creative and experimental. That was like the second-best news after knowing that I could be gay in the first place!” Findlay came to OOB’s staff in 1992, after a written correspondence with Kinney led her from Providence to San Francisco to work on the magazine. “The fact that Nan and Debie basically gave me their baby and let me take care of it…that was a blessing.”

However, Findlay expressed frustration at the financial reality of OOB — namely, that it didn’t make any money. Findlay says the original creators of the magazine weren’t interested in making money, but in “making waves” — Findlay, however, dreamed of creating a lesbian publishing company able to pay its contributors and staff. After OOB’s first folding in 1994, Findlay was a part of the creation of Girlfriends, an offshoot of OOB’s motivations less interested in sex as a focus, and more interested in “critical coverage of culture, entertainment, and world events from a lesbian perspective.” In 1998, due to the marketability and subsequent better financial straits of Girlfriends, Findlay as editor was able to purchase and open OOB back up for publication and distribution.

“It was very difficult as an editor to be working with huge figures in lesbian literature at the time and be promising them $25 for a short story!” Findlay laughs as she says this. “That made my work very difficult. And when we couldn’t even pay them the $25 we’d agreed upon, that was even worse.”

Findlay describes resurrecting OOB as a “labor of love,” which lasted until 2006 when, similarly to the first shuttering, the magazine came to a close due to financial instability. While she says this was “personally devastating,” OOB’s newfound irrelevance was something of a bittersweet progression: With the advent of the Internet, print magazines were going out of fashion, and lesbians and other queer people were more easily able to find one another in chat forums and email chains. The early aughts and the years after found an explosion of forward progression for LGBTQ+ rights, and while we are nowhere near a queer utopia, it’s no question the world OOB was created for has changed for queer people for the better — in ways that, unfortunately, made that same magazine obsolete.

Admittedly, “obsolete” is quite a harsh word, and not quite the right one: While the magazine doesn’t exist in the same capacity it used to, its influence on lesbian sexuality and literature cannot be forgotten, even though some may try. I think about this while reading Susie Bright’s Substack, interviewing Heather Findlay, or walking through a warehouse party in Austin, Texas: The bravery of lesbians young and old still astounds me, and the reverence for those that made OOB come to be is palpable. Who’s to say if a place like Autostraddle would even exist without it! I am thankful to be a descendant of folks like Bright and Findlay and thankful still that the legacy of OOB is being remembered so many years after the fact.

Elegizing a magazine like OOB today is in service of not forgetting history. Queer history builds on itself and lays groundwork for the present and beyond. Could we truly have Chappell Roan singing about “getting the job done” on Saturday Night Live to raucous applause without Cottrell’s erotic photography? Could we have Bottoms, a sleazy lesbian-sex comedy, without the lesbian strip shows hosted to pay for the printing costs of the magazine? We do not live in a vacuum — it is easy for those of us lucky to live through “the lesbian renaissance” of our pop culture, to forget to pay our respects to those who made it possible to be inundated with this sapphic deluge. Queer art like Chappell and Bottoms, while popular and successful in the mainstream, are so appealing because of their refusal to be palatable to heterocentric audiences. Despite Chappell’s fiery rocket to the top of the music world, her work at its core is extremely disinterested in shrinking away from her lesbianism, but more specifically, away from her distinctly-lesbian horniness. There’s “Red Wine Supernova,” which boldly begs for the “long hair, no bra” female muse to “put her canine teeth in the side of” Chappell’s neck. Or “Naked in Manhattan,” where she desperately repeats “touch me” in increasing volume. Her music is not just about being a gay woman, it’s about being a lesbian who fucks. Bottoms is a gay Superbad, in which the central conceit is sad horny lesbians doing whatever it takes to get laid.

Many lesbians may not see this as progressive or good (similar to lesbians of the 1980s sending hate-mail to OOB’s HQs). And to be fair, the oversexualization of lesbian relationships is an unfortunately time-honored tradition in media, pornographic or not. However, to assume artists like Chappell fall into this category is to deny lesbians the agency of their own sexuality, much like the very media such critics seek to malign. It is different: Marti Noxon quotes TV execs’ response to Buffy the Vampire Slayer’s lesbian relationship, as “They can [kiss] once, but not twice — because that means they enjoyed it.” When lesbians own their sexuality, when they prove they are doing it for themselves, and because they like it, this is still a radical, crucial ownership, the kind that OOB made a pillar of its mission. Perhaps even especially now, in a time where interest in lesbian culture by the straight mainstream feels exciting but also treacherous, this is what we should return to. It’s not that we can’t share with the mainstream — but it is special to remember we do not exist and prosper because straight people gave us permission. We do so because lesbians and queer people before us demanded it, in the street and in print.

If you’re interested in learning more about the history of OOB, subscribe to Bright’s Substack, watch this video, or peruse Cornell’s “Radical Desire” exhibit. If you’re lucky enough to have access to it, Brown University’s John Hay Library contains extensive archival materials of the magazine as well. The GLBT Historical Society in San Francisco also has archival materials of the magazine.

What a great exposition on the importance of knowing our history and how it shapes the present. I am here for this queer history content. Off to enjoy the digitised OOB now….

thanks for reading! we’d definitely love to do more of this work!

Can I just say?…..HELL YEAH. Thank you for this work, Gabrielle!!!

This is fantastic!!!!!

Yeah

I love this. A small correction: On our Backs was published through 2006, not 2002!

Such a great article! Is it 40 years already?…

Please more of this type of researched content.

Super article! I always think Lois in Dykes To Watch Out For would’ve modelled for On Our Backs, & ofc Dykes appeared in it quite a lot. & so many other writers- a treasure trove…

This post is the Autostraddle i love

Fun fact the research for love lies bleeding used this magazine as a reference

I love this so much 💗 this is definitely the kind of thing I subscribe to AS for! I’d vaguely heard of OOB, but didn’t know much, so I really appreciate the deep dive and references for further reading.

What a fantastic piece! I love the connections between the historical work OOB did in expressing lesbian sexuality to modern expressions in our current pop culture. Can’t wait to sink my teeth into some of these links!