This is the last piece in a partnership between Autostraddle and Transgender Law Center to provide data and reporting on why anti-trans violence occurs. Read more of the series. You can also find more data compiled by Transgender Law Center here.

On February 25th, 2020, Alexa Negrón, a Black trans woman experiencing homelessness, was killed in Tao Baja, Puerto Rico.

After police were called on her for using a McDonald’s restroom, patrons of the restaurant posted videos of the interaction on social media, spreading false rumors that she was a man in disguise, peeping on women in the bathroom — flames that were fanned by rightwing media.

Within 24 hours she had been shot. The horrific attack was also filmed, and widely shared.

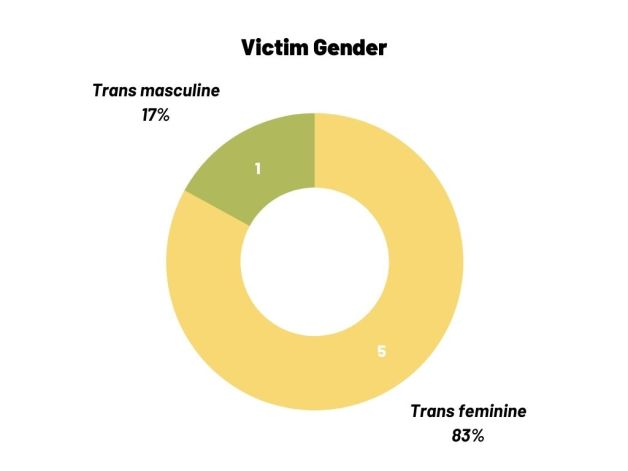

Six known trans murders occurred on the island in 2020 — five trans women and one trans man—the majority of whom were Black, Indigenous, and poor, experiencing housing instability and supporting themselves through sex work. Trans and queer activists on the island say Alexa’s murder didn’t merely mark the beginning of this violent wave, but that it’s emblematic of the intersecting systems and struggles that coalesce to threaten Boricua trans lives.

Puerto Rico has been rocked in recent years by two major hurricanes, earthquakes, blackouts and other failures of infrastructure, all of which have been compounded by the COVID-19 pandemic. The barrage of catastrophes—which resulted in thousands of deaths—left thousands more to process profound trauma, robbing many of any sense of stability.

While such events could seem merely unfortunate, activists say they are a predictable result of the island’s centuries-long battle against imperialism, most currently in the form of its status as a U.S. territory.

“Anti-trans violence is rooted in our colonial structures,” said Dania Warhol, founder of Espicy Nipples, a transfeminist network centering the Black trans experience in Puerto Rico. They cite religious fundamentalism—the remnant of Spanish colonialism that paints trans people as depraved—but also imposed legal frameworks that limit possibilities for how oppressed communities respond to crises that are often a direct result of U.S. exploitation of the island.

An example of this is the declaration of a recent state of emergency over gender-based violence—issued by newly-elected governor Pedro Pierluisi—a hard-fought battle won in the wake of protests responding to a sharp rise in intimate partner violence in the wake of Hurricane María, and then again during COVID-19. While Pierluisi has stated publicly that the executive order does cover trans and gender-nonconforming people, it does not explicitly say so in the law.

“We want the inclusion of trans people in this state of emergency, and we want their inclusion in writing,” emphasized Pedro Julio Serrano, founder of Puerto Rico Para Tod@s. “It is a victory, but we need to make sure it includes everyone targeted by gender violence.”

Dania Warhol remains wary of the state of emergency because of its focus on expanding the powers of government agencies. “When they declare a state of emergency, they usually want to take away our rights,” they said, noting that similar orders in the past gave disproportionate amounts of resources to law enforcement. “Giving more power to the government and to the state isn’t something we can afford right now.”

Many of the same laws outlined in the Biden administration’s touted Equality Act have existed in Puerto Rico for years. Out of all U.S. states and territories, Puerto Rico ranks 20 out of 56 in terms of legal protections for LGBTQ individuals. Yet, its inclusive laws are enforced unevenly, with police often playing a leading role in discriminating and perpetrating violence against trans people.

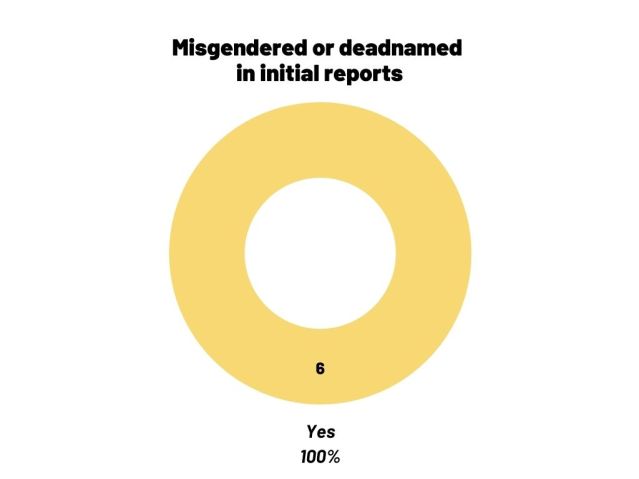

Puerto Rican police are described by trans activists as having a pattern of harassing and assaulting sex workers, immigrants, and women, defending perpetrators of gender-based violence while criminalizing their victims. In all six trans murders that occurred last year, police misgendered the victim every time. Activists claim officers regularly sensationalize trans survivors in their reports, which are often shared verbatim by local media, resulting in the exact type of misinformation that led to Alexa’s murder.

“We can’t rely on the police here,” said Joanna Cifredo, reigning Miss International Queen of Puerto Rico, and spokesperson for Arianna’s Center. She describes a protest she attended in October of 2020 at la Oficina de la Procuradora de las Mujeres (the Office of the Attorney for Women), drawing attention to government inaction on violence against trans women. Upon returning to their cars, which were legally parked in a nearby lot, all the participants’ vehicles had been ticketed.

“The police were standing there with their motorcycles just to see our faces when we got the tickets,” Cifredo recalled. “Just to see the joy on their faces, I’ll never forget it.”

Only weeks before, police had dragged their feet in an investigation after a 19-year-old cis woman, Rosimar Rodriguez, was abducted from in front of her home. Despite pleas from her mother, it took four days for officers to take any action. Her body was discovered only two miles from where she had originally been taken.

“When we protest in front of the governor’s mansion, police come out like G.I. Joes for people holding pots and pans, wearing flip flops. But when it comes to looking for a girl who’s been abducted, it takes four days.”

“Police are an instrument of oppression,” Serrano corroborated. “We’ve done trainings for them, passed laws, but they are not implemented correctly. I myself have been in the rooms, having these conversations with police chiefs. But it goes in one ear and out the other. It doesn’t trickle down to their subordinates.”

In addition to being targets for state violence, trans organizers also describe mistreatment from the Puerto Rican left. Though trans people have been integral to grassroots movements across the island, they say they are simultaneously left out of the work of mainstream feminist groups and treated as a distraction by radical organizations, who often see trans and queer struggles as secondary to Puerto Rican independence.

On July 25, 2019, trans and gender-nonconforming organizers staged the now-iconic Perreo Combativo, a raucous dance party in front of la Catedrál in Old San Juan as part of the massive #RickyRenuncia protests, calling for the resignation of then-governor Ricky Roselló.

“At the same time that we were having this big dance party,” Dania Warhol recalled, “other protesters were calling us names, saying mean things about the way people were dressed and about their bodies.” In response to threats, trans people and their allies formed a line between dancers and their harassers. “In that moment, we had to protect ourselves.”

While the scene Warhol describes is indicative of the violence trans Puerto Ricans face from all sides, it also illustrates the ways trans communities are organizing to provide each other with the exact spaces, protections, and resources the state denies them.

While recent tragedies on the island have hit already-struggling trans communities particularly hard, they have also led to an explosion of organizing. In the last five years, three new trans-run clinics have opened, and countless organizations have formed. Communities are employing a range of strategies to address anti-trans violence, including policy change, continued protest, and building solidarity economies on the ground.

“I joined the Ms. International competition because it provided a platform,” said Cifredo of her title in the popular pageant. “I see myself as a Trojan horse who can now get at these tables and be a voice for the community.”

On the one-year anniversary of Alexa Negrón’s murder, Cifredo organized a meeting between trans community members and candidates for public office. Some of the biggest issues they hoped to push were the decriminalization of sex work, providing housing for trans elders, and ensuring that gender-affirming healthcare is widely accessible—including in rural communities.

Espicy Nipples organized a Queer Brigade which did outreach to trans sex workers, distributing emergency resources, while also conducting surveys, gathering information on the most lacking supports. “People aren’t just telling us they need condoms,” Warhol said. “We’re hearing, ‘I need a house, a cell phone, to be included in a medical plan.’’’

Trans community members have created a host of projects to support one another during the pandemic, amidst a decided lack of aid from the U.S. government. La Laboratoria Boricua de Vogue offers voguing classes, and throws outdoor balls. Bartering systems where drag performers swap clothes, do each other’s makeup, and skillshare have become a common way to build networks and pool resources. Live streams where artists perform and give tutorials have helped trans people crowdsource needed funds.

After two trans women, Serena Angelique Velázquez Ramos and Layla Pelaez Sánchez, were found in a burned out car in April 2020, hate crime legislation brought federal charges against their suspected attackers. However, this legal action allowed the U.S. government to pursue the death penalty, overriding the Puerto Rican constitution which expressly prohibits it. Trans activists are calling against the use of capital punishment, demanding Serena and Layla’s lives be honored in the ways their community determines, not by further entrenching U.S. colonial authority.

“We want to take power away from the state and put it into our communities,” says Warhol. “Our community needs funding, education, housing, to create our own sense of security.”

Up to now, Warhol says the demand to defund police has largely been seen as a cry from U.S. activists, but Black trans Boricuas hope to shift that perception: “’Defund’ is not popular here. You don’t hear it a lot, but we’re trying to change that.”

Trans struggles in Puerto Rico demonstrate that inclusive legal language alone is ineffective at protecting trans lives. Approaches to liberation that focus on passing laws, but not redistributing resources, inevitably fall short. Expanding state power further cements the same inequalities that compound trans suffering, and fuel trans death. Only by placing needed resources directly in the hands of trans communities — healthcare, housing, food, education — can trans people finally have the autonomy they need to support themselves and each other, a task for which they have already demonstrated a profound capacity.

The political landscape remains fraught, but as leftist struggles across Puerto Rico and its diaspora seek true independence for the island, trans activists insist they are not a distraction, but central to Puerto Rican liberation.

“Trans people are modeling what it means to be authentic,” said Cifredo. “To fight for a better society, to heal, and to actualize love in policy and in space.”

This is a fantastic and important post. Thank you so much for writing it!

Been reading autostraddle for 7 years, first time i see my community represented! Thanks for this

Thank you so much for writing it!

We have to end all types of violence, especially against minorities. No more intolerance

While the scene Warhol describes is indicative of the violence trans Puerto Ricans face from all sides, it also illustrates the ways trans communities are organizing to provide each other with the exact spaces, protections, and resources the state denies them.

While the scene Warhol describes is indicative of the violence trans Puerto Ricans face from all sides, it also illustrates the ways trans communities are organizing to provide each other with the exact spaces, protections, and resources the state denies them.

While the scene Warhol describes is indicative of the violence trans Puerto Ricans face from all sides, it also illustrates the ways trans communities are organizing to 希愛力雙效

Key5 is great for everyone.