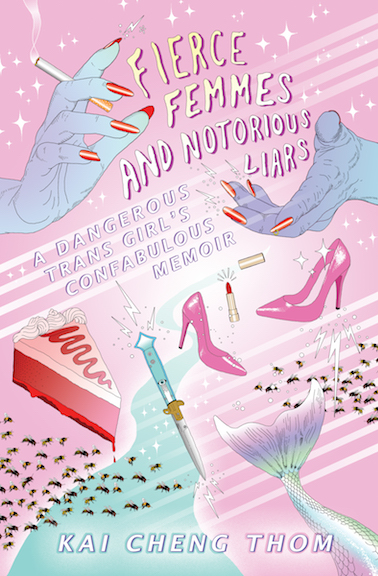

Kai Cheng Thom’s Lambda-nominated debut novel, Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars: A Dangerous Trans Girl’s Confabulous Memoir, is a captivating tale of betrayal, murder, mysticism, legend and compassion. I devoured it within a few days and was terribly sad when I closed it, wishing that Thom could write a never-ending tale for every trans girl who needs more escapism, more vision and more badass resiliency.

That’s exactly what Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars creates — a magical place for every trans girl to insert herself into the story. A place where we belong. The beauty of this pseudo-memoir — which acts as a satirical commentary on the roots of trans literature as based in memoir — is that we get to identify with more than one character who’s canonically and unapologetically a trans woman, and not sensationally named as trans in every sentence, either.

For once, we get to insert ourselves as girl gang members, sisters, mothers, witches and goddesses. We get to be bald and sex workers and seamstresses and runaways and dancers and jealous friends. We get to be complex. We get to have a sisterhood of vengeance and victory. We get to be femmes who kiss and fuck one another, who fight back, who murder cops, who hurt each other, who fall in love, who survive tragedy, who forgive each other, who create homes together, who choose the kinds of lives we want to live.

As much as I loved reading Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars, it also hurt. Violence and danger are major themes, and Thom writes painfully realistic characters as able to hurt as they are to love. The main character falls into a self-fulfilling prophecy of thinking she’s just an abusive person, and therefore — often unintentionally, though sometimes purposefully — hurting those that are kindest to and most supportive of her. Like the pocketknife she carries that hurts her as she loves it, she is a blade that cuts those that she loves.

Most painful was the incorporation of trauma and tragedy in the femmes’ lives. Thom’s wildly imaginative narrative also includes legends of murder, death and violence in the lives of trans femmes. As much as I wanted this book to be fun escapism, the consistent violent reminders of what our real lives are like pinched me out of the surrealist fantasy.

But like our real lives, some of us survive to tell these challenging stories in creative ways that defy the systems and structures that enact violence onto us.

Over Skype, I asked Thom about memoir that isn’t memoir, the different sides of trauma, her literary choices and more in Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars. Note that there’s mild discussion of child sexual and physical abuse.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Luna Merbruja: I’ve been reading some of your interviews and promotional materials, and I’ve been finding that you’ve consistently said this is not an autobiography. [KTC laughs] There seems to be some confusion about that. How much of this was pulled from your experience? How much did you consult other people?

Kai Cheng Thom: The title itself is “a memoir,” but then it’s not a memoir.

The most honest answer I can give is that there are surrealist and magical realist elements, and then there are heightened elements. I’ve never [laughs] accidentally killed a cop, or if I had I would have to say I hadn’t to keep my plausible deniability or whatever.

There’s an amazing line in Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire by Blanche Dubois, who is this terrible, aging Southern belle type. She’s lied to everyone in her life and then her boyfriend is like, “Why are you such a liar?” And she goes, “I never lied in my heart.”

The narrator’s emotional experiences [in Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars] are ones that I’ve all lived and experienced. The facts, or the details of the narrative, are heightened, surrealized and embroidered upon. Some of them are drawn from my life, but then brought into this mystical place.

In terms of the other characters, they each have a piece of me. As any author, I brought my own perspective to each of those characters. Most of them started off based on real life trans women, and then, much like the narrator, the details of their life stories, their appearances, or their personality have been heightened and mythologized to evoke a story that has a real feeling. Also, it plays with this idea of fiction being able to express truth better than fact.

LM: Early on in the book, there’s this character named Ghost Friend.

KCT: Yeeeeah! [Laughs]

LM: I had a hard time pinpointing what Ghost Friend was supposed to represent or be a metaphor for.

KCT: I love that you picked up on Ghost Friend. Most people ignore Ghost Friend or skip over them, but they’re super important to me! Ghost Friend is the flip side of trauma. We have the killer bees that are inside the protagonist’s body. They’re the sort of dark side or painful side of trauma, the part that keeps her from connecting to other people, the part that causes her to punish herself, all this kind of wicked stuff.

Ghost Friend is also a result of trauma, but the beautiful side. The side that allows her to connect with herself in particular ways. The side of her that really loves herself, that understands what she needs through the lens of trauma. In some ways it also brings her to close herself off to other kinds of intimacy, which is why when she’s finally opening herself up and being intimate with Josh at the end of the book, she has to give up Ghost Friend. Sometimes we need to give up parts of ourselves so we can receive from someone else.

LM: That’s helpful to conceptualize that Ghost Friend is in contrast to the killer bees. When I first read The Lessons of the Bees chapter, I definitely picked up on some child sexual assault undertones, which, may or may not be it. For me, it was really obvious, and throughout the book it kept coming up and feeling like triggers and traumas from that early experience. Is that an intentional choice, or, what type of trauma, if any, were you trying to create with the killer bees?

KCT: You know what’s interesting? Another trans woman reviewer brought up the killer bees and said she wasn’t sure if the killer bees were a metaphor for sexual assault, or for body dysphoria. Then she didn’t ask the question so I never had to answer it.

To get real for a second, I experienced a lot of trauma in childhood as many trans women of color do. I can remember moments of physical abuse and verbal abuse. I have a whole bunch of symptoms of sexual abuse also, but the actual event of sexual abuse — like the incident of it — I can’t remember.

Throughout my life, this is something that has been haunting. Kind of like, “Why do I have this reaction?” or, “Why didn’t people tell me that this thing happened when I have zero memory of it?” I know that it happened because of the way the story is told to me, but I don’t have an image or sensory memory or physical memory to substantiate that.

This is what lies at the heart of this concept of lying being able to express the truth. Me explaining sexual assault or my experiences of abuse to people, and not having the memory and being called a liar — those two things [end up] being tied together.

The idea of writing a memoir that had [the bees] at its heart, I and the protagonist didn’t have to stick to the facts. In this sort of cold, bullet point way, like, “This is what happened. This is what I remember, and this is something that can stand up in court.”

Because sometimes the reality of what is in our bodies just is. We shouldn’t have to prove it. That’s what those bees are for me, this powerful embodied experience without memory, without story — given a story of its own, and given an image of its own.

LM: I know I’m hitting in the heart with these questions [laughs].

KCT: Yeah! It’s so good, so good.

LM: This book challenges the memoir genre, and especially how trans memoirs are always saturated in trauma and focus on a cis audience. How did you decide what trans women characters to portray? At one point Kimaya talks to the protagonist about being “fishy,” and it seems like there’s a dichotomy between “fishy” being equated with success and the “not fishy” girls being disgraceful.

Can you also talk about the choices you made to portray trans women characters as being on the street doing different types of sex work?

KCT: Yeah, they’re all doing various types of sex work, some very different from others. I love that question and I’m really glad you asked it because I think a lot of cis reviewers or interviewers have shied away from this question. [Both laugh]

This is super real and a super important dimension of accountability around the novel as well. I’ve been wondering about it, particularly now. Why did I choose to represent the trans women that I did? Why is my protagonist the kind of trans woman who is named fishy?

Primarily, I wanted to represent a diversity of trans women, a diversity of trans women of color, and trans women who felt real. I knew that the only way I could do that was to draw from my relationships with real trans women and then fictionalize.

One of the relationship dynamics that has been really present in my life, in various ways, is this concept of fishy or not. And experiencing my own jealousy towards other trans women that I feel are more passable than me, or more successful in terms of capitalist types of success. Then of course, experiencing this other side of the jealousy of others toward me, because I have been really successful in terms of moving through the non-profit world and becoming a psychotherapist. This is a rare thing, and it has a lot to do with my privilege as a light-skinned, East Asian trans woman of color who went to university.

Grappling with that, and the disparity in relationships and the animosity and the jealousy and the sadness and the guilt that can come up, is really important. In terms of who the protagonist is, that conversation where the protagonist is named as fishy by Kimaya is an example of several of those conversations that have happened in my own life.

I wanted to represent [fishy] in a way that wasn’t, “Oh poor me, I’m so fishy!” There also wasn’t pitying of people who were less passable than I am, and also owning up to the fact that I’m not passable all the time.

LM: What feels important to you to share right now?

KCT: I see Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars as a huge ongoing conversation that’s just starting to happen between trans women, and particularly trans women of color, who are storytellers of any kind. The trans lit movement is white-dominated sometimes, and shuts us out. Now we have these amazing books by people like you (author of Heal Your Love), and also jia qing wilson-yang who wrote Small Beauty, and Gwen Benaway, and Jennifer Joshua Espinoza, and I think we all have complicated feelings about each other but also love each other.

I want to emphasize that I see this book as a collection of stories other people are putting out as well as me. I would never want it to be understood as the trans-woman-book-to-end-all-trans-women’s-books, or the most important book, or in competition. I think it’s such a flawed book in so many ways, I think I’m probably going to hate it ten years from now when I’m like, “Ugh, why did I think those things!”

To sum up, I’m grateful and humbled by the fact that you read this book and you liked it, and I’m really grateful and humbled at the fact that other people are reading this book. I encourage folks to go out there and read and support other trans women of color writers. Let’s all kick butt together.

Comments

This interview was so good! My entire book club read and LOVED this book and we had a real lengthy discussion about Ghost Friend. It was great to hear the author’s perspective and I look forward to reading more books from her in the future!

this is fantastic! i love reading about the decisions that brought a book into being and how the world of a book is developed, and these are such good, substantial questions and such thoughtful answers. thank you so much, luna and kai cheng!

This was a lovely interview! I’ve been eager to get my hands on this book for a while, and now I’m even more excited about it!