This week, the Employment Non-Discrimination Act aimed at providing federally mandated workplace protection to gay, queer, trans and non-gender-conforming people has stepped back into the spotlight. We’ve seen it most recently in 2007, 2008, and 2011, but it failed to pass into law. On Monday, the Senate voted to once again consider ENDA, and today, the Senate voted to pass it. For the first time ever, ENDA is being introduced in a world where DOMA is ruled unconstitutional, DADT is over, and public opinion polls on gay people are at a record high. Does that mean this is finally ENDA’s moment to succeed? Well, it’s complicated. First let’s look at why ENDA matters so much in the first place, and why we’ve been going back and forth on it for over thirty years.

Why does this even matter?

by Yvonne

Currently, no federal law exists to prohibit employers from discriminating against LGBTQ workers, even though 9 out of 10 people think there already is a law protecting these rights. Only 21 states and D.C. have laws that prohibit employment discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and only 16 and D.C. do so on the basis of gender identity. That means in the majority of states it is perfectly legal for employers to fire, not promote or even hire queer individuals solely based on their sexual orientation or gender identity which are irrelevant to their job performance, qualifications or skills.

According to a 2011 report by The Williams Institute, 27 percent of LGB workers said they had experienced discrimination in the workplace and the number jumps to 38 percent among those who are out at their job. When surveyed separately trans* respondents reported even higher rates of employment discrimination with 78 percent of them experiencing at least one form of harassment or mistreatment at work because of their gender identity.

Discrimination, harassment and mistreatment at work can cause low job performance which can lead to unemployment because of their performance or for a variety of other reasons. Without an income that person can’t support their family, pay for bills, groceries, daily necessities, medication and can eventually fall into poverty if this cycle continues. With ENDA, LGBTQ workers will be protected and have a chance to make a living and participate in this society, just like everyone else.

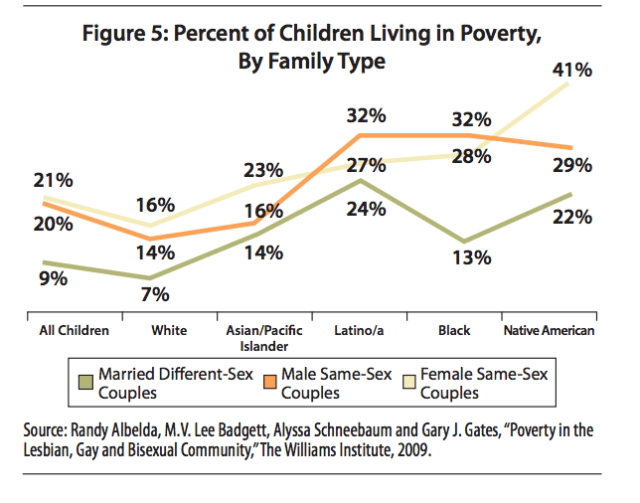

To queer workers, ENDA is a vital piece of legislation that greatly impacts their families, especially those with children. “One in five children in same-sex-couple families are living in poverty, compared to one in 10 children living with married different-sex parents”, according to a 2011 report by the Movement Advancement Project, Family Equality Center and The Center for American Progress. The report also says that the average household income for same-sex couples raising children is 20 percent less than the average household income for heterosexual married couples. On top of that, same-sex families of color (who are more likely to raise children than white couples) are more likely to live in poverty than white same-sex families.

Trans* workers suffer far worse than LGB individuals in the workplace. Like this cool infographic explains, they have to deal with coworkers and supervisors misgendering them, sharing personal information inappropriately, asking questions about surgical status. They’re also denied access to bathrooms, face to face interaction with clients and being sexually or physically assaulted.

According to a comprehensive study by the National Center for Equality and the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force titled “Injustice at Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey,” 47 percent of the respondents said they experienced being fired, not promoted or not hired because of their gender identity. They also found that those who lost their job due to bias have a household income of $10,000/year and live in dire poverty at six times the rate as the general population. And of course, race multiplies the discrimination: “For Black, Latino/a, American Indian and multiracial respondents, discrimination in the workplace was even more pervasive, sometimes resulting in up to twice or three times the rates of various negative outcomes.”

These adverse job outcomes can lead to unemployed trans* folks to turn to underground employment, like sex work or drug sales, in order to survive. They then become incarcerated, homeless and become HIV positive at higher rates than the general population.

An income buys American citizens food and rent but also economic, social and political power. Unemployed LGBTQ workers are voiceless and cannot fully participate in society. ENDA would provide these workers some form of power with which to combat unemployment and discrimination in the workplace, giving them the chance to be on a more equal footing with straight and cis counterparts in the workforce. Although the question of enforcement is always present, ENDA could hold the key to setting up legal precedents that could end many of the problems outlined above. Most importantly, ENDA would come from the federal level, which could be a saving grace for many employees who know that if they have to wait for their individual states to recognize employment discrimination, they’ll be waiting forever.

How did we get here? The history of ENDA

by Cara

The first bill technically named ENDA went up to bat in 1994. But if you want to trace ENDA’s true legislative history, you have to dig a quarter of a century deeper, way back to 1969’s Stonewall Rebellion. Although the American LGBT rights movement had grown quietly for decades beforehand, Stonewall was its catalytic turning point, the “hairpin drop heard ’round the world” that cleared the way for the first Pride parades, the first large-scale protests and demonstrations, and a major leap in organizing. As Franklin Kameny, an early organizer, remembers, “By the time of Stonewall, we had fifty to sixty gay groups in the country. A year later there was at least fifteen hundred. By two years later… it was twenty-five hundred. And that was the impact of Stonewall.”

This explosion of visibility finally brought LGBT issues into the public consciousness, and, eventually, into the political sphere as well. Five years after the uprising, two representatives—Bella Abzug and Ed Koch, both New York Democrats—introduced the Equality Act of 1974. Koch was “among the earliest vocal supporters of gay rights on the national scene,” though he later lost favor with many when, as the mayor of New York, he largely ignored the AIDS epidemic. Abzug was, honestly, one of the coolest congresspeople ever, a civil rights lawyer and feminist icon who was one of only twelve women in Congress and spent decade battling for social justice, anti-war, and pro-environmental legislation while wearing enormous hats. Together, they wrote and introduced the Equality Act, which proposed to amend the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to include bans on discrimination based on “sex, marital status, or sexual orientation” in employment, housing, and public places such as museums and restaurants. (Notably, it excluded protections for trans* people).

FUN FACT: ABZUG ALSO APPARENTLY DID A GREAT MARLENE DIETRICH IMPRESSION

Although “hopes were high” for its passage, the bill flamed out in committee, beginning a sad, decades-long trend. Similar bills were born and died throughout the 1970s. While Congress spun its wheels, the national environment was changing. During the 1980s and ’90s, conservatives like Pat “Culture War” Buchanan and Anita “Save Our Children” Bryant built up enough of an anti-gay backlash to slow down the burgeoning movement. Meanwhile, the AIDS crisis redirected the energy and priorities of many LGBT groups and activists, both socially and politically—for example, in 1986, the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force began “years-long lobbying efforts to fend off viciously anti-LGBT amendments to AIDS funding bills,” leaving fewer resources for pure equality legislation.

Eventually, the issue made its way back to Congress. Gerry Studds, a Massachusetts Democrat and the country’s first openly gay congressman, introduced the Employment Non-Discrimination Act of 1994, which narrowed the scope of the proposed law to cover employment discrimination only. Gender identity provisions were once again not included. Although the bill had 137 co-sponsors, it once again died in committee.

That fall, Capitol Hill underwent what has become known as the “Republican Revolution” — the GOP took over the House and Senate and gained ten governorships, and exit polls showed a massive increase in self-identified conservatives, religious conservatives, and evangelical Christians. Although that didn’t stop individual representatives from trying to pass ENDA—a version of it was introduced in every congressional session from 1996 to 2005—it did make it hard for the bill to get much further than that. (Once, in 1996, massive support from Democrats did bring it to a vote in the Senate, where it lost 50-49. The missing 100th vote would have belonged to David Pryor, an Arkansas Democrat who was dealing with a family emergency and couldn’t make it back to the Hill—if he’d voted yes, Al Gore would have broken the tie, and it would have passed). In the meantime, individual states slowly began adopting their own non-discrimination laws, and the government did the same for federal employees, banning discrimination based on sexual orientation in 1980 and expanding this protection to trans* workers in 2009.

In April 2007, Barney Frank (D-MA), Chris Shays (R-CT), Tammy Baldwin (D-WI), and Deborah Pryce (R-OH) finally introduced a version of ENDA that included gender identity within its protections. That, too, died in committee. For their next try, that September, “Frank and House leadership decided to split the measure in two” and introduced a version of ENDA without gender identity protections, as well as a separate bill that would provide those protections. In turn, hundreds of LGBT and ally organizations withdrew their support from the bill, stating in a letter of protest:

“We ask and hope that in this moment of truth, you will stand for the courage real leadership sometimes demands. You each command enormous respect from all of us and we do appreciate the difficulty of balancing a variety of competing demands. But the correct course in this case and on this legislation is strikingly clear. We oppose legislation that leaves part of our community without protections and basic security that the rest of us are provided.”

KYLAR BROADUS, SPEAKING ON BEHALF OF ENDA IN 2012. BROADUS IS THE FIRST TRANS* PERSON IN HISTORY TO TESTIFY BEFORE THE US SENATE.

The House passed the non-gender-identity-inclusive bill in October 2007, but the Senate never voted on it, and advocacy groups and lawmakers came to a consensus that all future versions of the bill would be inclusive. In the following years, a comprehensive ENDA was introduced over and over again and, as before, died in various committees—until 2011, when committees stopped letting it die of exposure and instead began tossing it to each other like a hot legislative potato.

After picking up revisions from the Education and the Workforce, House Administration, Oversight and Judiciary Reform, Judiciary, and Health, Education, Labor and Pension committees, S.815, aka the Employment Non-Discrimination Act of 2013, aka the latest version of an idea sane people have been trying to put into practice since 1974, finally landed in the Senate again—this time with a decent chance of passing.

So what’s happening now?

by Kaitlyn and Rachel

The now gender-identity-inclusive ENDA most recently approached Congress in May, when it was introduced in both the House and the Senate. The Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee cleared the bill in July with bipartisan support, but a House version has not yet been discussed by GOP-controlled committees.

House Speaker John Boehner (R-Ohio) affirmed Monday his concerns about the bill, announcing through a spokesman that “this legislation will increase frivolous litigation and cost American jobs, especially small business jobs.” Without Boehner’s support, it is unlikely that ENDA will make it to a vote in the House. In the Senate, however, ENDA has made significant progress.

On October 30, Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.) promised an ENDA vote in that body before Thanksgiving. Republicans made with the filibustering, as they do, but a successful cloture vote came November 4, when 54 Democrats and seven Republicans voted to end debate.

The legislation’s two Republican cosponsors, Sens. Susan Collins (R-Maine) and Mark Kirk (R-Ill.) were joined across party lines by Sens. Kelly Ayotte (R-N.H.), Orrin Hatch (R-Utah), Dean Heller (R-Nev.), Rob Portman (R-Ohio) and Pat Toomey (R-Pa.). Portman and Toomey were late additions, persuaded in a cloakroom just off the Senate floor when the absence of Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-AK), who voted for the bill in committee, demanded the support of at least one more Republican legislator.

Much of the criticism directed at the current version of the bill centers on its broad religious exemption, which would expose to discrimination all employees associated with a wide range of religious institutions. From the New York Times:

“The exemption would extend beyond churches and other houses of worship to any religiously affiliated institution, like hospitals and universities, and would allow those institutions to discriminate against people in jobs with no religious function, like billing clerks, cafeteria workers and medical personnel.”

And while ENDA advocates fear the broad exemption will leave an untold number of workers vulnerable to their religiously affiliated employers, religious groups are stating their own fears that it isn’t inclusive enough because it does not specifically enumerate who may discriminate, when and why. Many worry that the vague language will expose religious businesses to litigation — but legal recourse in cases of discrimination, as Zack Ford at ThinkProgress argues, is the whole point of ENDA.

Republican Senator Pat Toomey introduced an amendment to ENDA that would actually expand its religious exemptions to include even more businesses and institutions than it already does, but this amendment was voted down. Toomey went on to vote for ENDA’s passage, even without his amendment included in it.

Today, the Senate voted to pass the current version of ENDA, which includes gender identity and which doesn’t have any extra religious exemptions added on to the exemptions it’s had for years. This is the first time the Senate has voted on the comprehensive ENDA bill and passed it, and it wasn’t even a particularly nailbiting or partisan vote — the fact that the bill passed 64-32 may be a sign that the climate is, in some ways, different than it has been in the past; that the nation is at least marginally more ready for ENDA than it has been in the past.

Unfortunately, that doesn’t necessarily mean the House is ready as well. So far, the House hasn’t given any indication that it’s going to vote on this at all, and it may not. Tammy Baldwin has publicly called for Boehner to have a vote, but there’s no guarantee that will happen, and if it did, it’s not likely that it would pass the vote. As it stands now, there don’t seem to be indications that this is finally going to be the year that ENDA becomes a reality. But there are indications that ENDA has been received better and gotten closer to passage than ever before, and if the long, circuitous history of the bill teaches us anything, it’s that the work done at each stage isn’t lost if the vote doesn’t come through. Instead, the work to get the bill as far as possible each time builds relationships inside Congress, educates the public, and advances the conversation. Even if Boehner doesn’t want to listen right now, there are other Republicans in the Senate and maybe even the House who might be, and the next time ENDA makes its way to the forefront, maybe they’ll be in a position to finally bring it into the world.

I knew it would pass the Democrat controlled senate. Somehow i had little hope that the speaker of the house would bring it to the floor. Maybe we should put some pressure on them to do so

Wow, thanks for clearing up this issue for me. I had no idea ENDA had such a long history!

Thank you so much for this. Linking everybody to this article right now, tbh. I’ve faced employment discrimination through pretty much my entire working career. This is such a big deal.

First of all, great job on this post!! Love the teamwork!

Like Tory said, I didn’t know ENDA had a long history. I never heard of it til this year, the gayest year/year of the gay. Anyway, I’m glad we’re taking another step forward in society and it’s good we’re spreading awareness on ENDA.

We are currently in an interesting position in Australia at the moment; we all have individual state laws which make discrimination based on LGBT*Q illegal, but there is yet to be one whole federal law.

On top of this, there are specific exemptions to the laws; for example, here in Victoria, under the Equal Opportunities Act 2010, religious institutions (surprise, surprise!) are still allowed to commit discrimination on the basis of sexuality.

My personal favourite excerpt from the EO Act is this gem:

‘Religious bodies and religious schools can also allow a person to discriminate against another person on the grounds of the person’s religious belief or activity, sex, sexual orientation, unlawful sexual activity…’

Essentially putting us homogays in the same category as people who have committed indecent sexual crimes.

Stay hopefull you guys! :-) Almost there… Thank to AS Team for this amazing post, such an interesting reading, even for non-american people like me! :-p

I personally feel you’re being far too gracious to Barney Frank. What he did in 2007 was sleazy, and underhanded and he forever lost his cred among large portions of the LGBTQ community and pretty much permanently soiled his reputation. I hope any other politicians and Gay Inc. organizations understand how throwing entire communities under the bus to get short-term “gains” is a corrupt strategy and they will be called out on it.

I don’t drop many responses, however i did a few searching and wound up here ENDA Passes the Senate: How Did We Get Here,

Where Are We Going? | Autostraddle. And I do have 2

questions for you if you do not mind. Is it simply me or

does it appear likje some of the resaponses come across as if they are left by brain dead folks?

:-P And, if you are writihg at other online sites, I would like to follow everything fresh you have

to post. Would you make a list of all of your shared sites like

your linkedin profile, Facebook page or twitter feed?