It has been almost ten years since I last saw her, and I miss her. Queer experimental filmmaker Barbara Hammer passed away last week at the age of 79, from ovarian cancer. When I heard the news, it felt like I had been scooped out, like I lost something. We didn’t know each other, but my life intersected with hers years ago, in a series of meetings and near-meetings. There were a lot of details I had forgotten about, and maybe tried to forget from that period of my life. All of it was dug up when I found out she had passed. I was sitting in a café in Seattle with a friend. It felt like my heart had dropped through my chest.

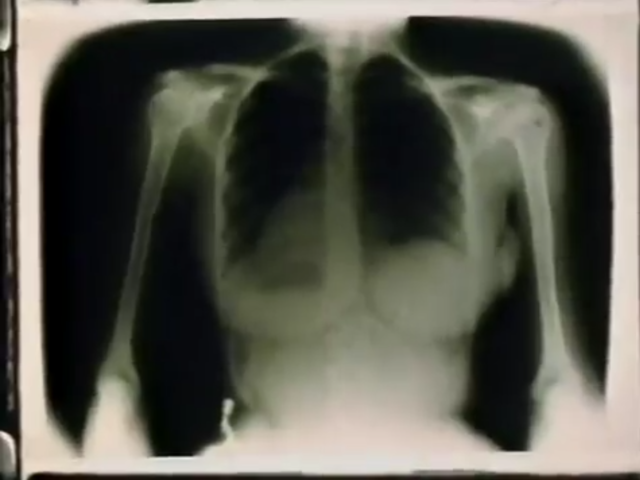

When I got back home, I sat down to watch her film, Sanctus. The screen is filled with the bodies of women and men, hollowed out by an x-ray machine. Their bones glow in a bright white, with spinal columns, scapulas, and humeruses moving, as if these bones are the articulating pieces of a marionette, suspended by invisible wire. At the center of the frame is a ribcage, hollow, empty, blank, the darkness split into halves by the spine. In this place I imagine where the heart should be, where the lungs should be, in the dark.

Sanctus (1990) by Barbara Hammer

It was so long ago I had almost forgotten: I wrote an article for Autostraddle on Barbara Hammer on October 11, 2011, when I was 23. It was only a few weeks before I would get engaged at the end of October, and a year before I would get married. Reading the piece now, I see the shape of myself as a very young queer person, glass-fragile. I see, in the tone of my writing, an anxiousness and an uncertainty that I feel now when I read the piece, as if it was baked in to me. I see myself as a series of hollows, and the bones that structured that emptiness around them. I think I needed a mother, then.

When you grow up queer and you’re young, you’re constantly looking for role models, for some kind of direction. You’re looking for some sign that will point you toward something, because so often it feels like you’re treading water, still and silent, in the middle of an ocean. In my late teens and early 20s, I found myself looking toward queer experimental film for my elders. I turned toward Sadie Benning and her film It Wasn’t Love, wide-eyed and so incredibly struck by lightning, the screen filled with a pixelated slow dance between two women. Toward Shu Lea Cheang and her film Sex Fish, which was one of the first times I could imagine queerness in relationship to race and being Asian/American, watching hands on bodies interspersed with images of fish and water. Toward Barbara Hammer and her film Dyketactics, watching the images of tangled hands and legs and soft grass suspended over images of her driving in a car, warm sunlight hitting her face, wind ruffling her hair.

It Wasn’t Love (1992) by Sadie Benning

I’m not sure why it was these strange, short films that had grabbed me so much. Maybe it was how they didn’t make sense in the way we might think a film should make sense — the films these queer women created were not about telling a linear story, or showing the character arc of a protagonist overcoming some kind of obstacle. Instead these films were a mesh and mangle of sounds and images, where bodies, surfaces and feelings were cut and stitched together in ways that seem so purposefully incoherent. Maybe what I was drawn to was how they relied on incoherence and feeling instead of tidy, simple boxes with simple answers and simple endings.

It matched up with my life and what I had been living through at the time, toward the end of college: a feeling that I was falling through and out of my family after I came out to my parents at 19; a feeling that I was treading water constantly just to stay breathing, and floating, so exhausted and lonely that the idea of moving toward anything in this state was impossible. I’m 31 now. I look back at this time and I see how much of a child I was in need of someone who might be able to take my face in her hands and tell me that I was okay, and that I was alive, and that I was good; you’re doing great.

Barbara Hammer was that for me. She was the evidence that living a queer life could be good, and long, and full of wonder at a time when I felt like this was all was out of reach. I have a copy of her book, Hammer!: Making Movies Out of Sex and Life that has been sitting on my bookshelf since college. On the title page are a few words, scrawled out in tight, curved handwriting that looks almost like my mom’s. It reads: “For Whit— An incredible career awaits you now— Here’s to Asian Queer Identities!” It is signed by Barbara Hammer.

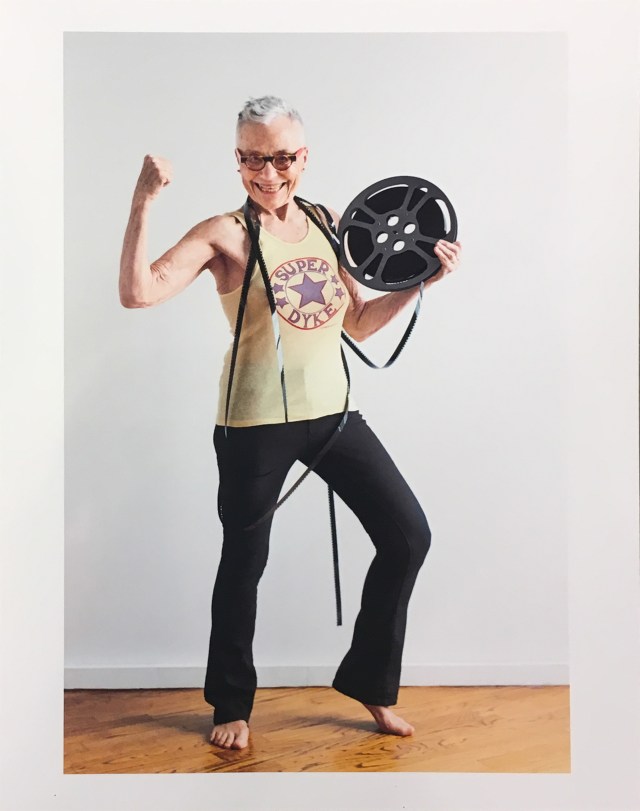

Vintage Beinecke: Superdyke (2018) by Barbara Hammer

What strikes me now is that her note was looking toward the future: something I could barely do myself, at 21. I don’t know what she saw in me, or who she thought I could become. I feel like she was looking at me from her position at the top of the mountain, and she could see what potential I had and what my life could be. In her note, she writes, as a queer woman to a queer child, I can see you, and you have so many beautiful and incredible things ahead of you. Maybe she could see what I needed, then: a push, a sign, a movement toward something in each second of every day, toward something remarkable. And I suppose I am that person, now, that Barbara Hammer wished me to be: a person whose present is beyond what I could have ever imagined or dreamed of at age 21.

I remember clearly what it was like to meet her that day: the energy she had, walking up and down the aisle of a small auditorium, talking animatedly about her filmmaking and her work; her openness as she listened to me talk to her excitedly about queer film and being Asian American. I remember her body as full of muscles and angles, her hair short and salt and pepper and spiky at the top. I remember her encouraging me in a way that I had been missing from other adults in my life. I remember feeling like I was meeting someone who was very important to me.

A Horse is Not a Metaphor (2008) by Barbara Hammer

I remember that she showed a film that day, A Horse is Not a Metaphor, which she released two years earlier. The film is about her first fight with ovarian cancer in 2008. I remember the film containing images of her body overlaid and interspersed with images from the hospital: the IV drips, the hospital rooms, the bedsheets. And I remember the horses that recurred throughout the film, pointing toward a possible way out, and through, the fragility of bodies and the institutions that house them when you are close to death. I remember her speaking about the film and her experience of the reality of death, and while I don’t remember exactly what she said, I remember the fact of cancer and death as something that didn’t quite feel like it had a hold on her, as she stood in front of me, all bones and blood and breath.

Now, I am ten years older, and I see the fragility of bodies around me in ways that wasn’t as clear when I was younger. I see it in the hands and wrists of my grandmothers, of my grandfathers who have passed now. I see it in the faces of my parents, and in my own face in the mirror. When I saw more recent photos taken of her from her Exit Interview in the New Yorker, I could see, too, in her body being cradled by her partner Florrie Burke, the body that had moved animatedly up and down the auditorium, the hands that scrawled out my name and hers in my copy of her book, the body that I had thought then, was invincible.

“On the Road, Baja California” (1975) by Barbara Hammer

Maybe this is the reason why I’ve returned to Sanctus, a film entirely about the body and its complex and fragile internals, its hollows and cracks. It’s a film that stands in contrast to the images Barbara Hammer is most widely known for: queer bodies touching, feeling, reaching toward one another, the surfaces of bodies, the muscles that pull bodies together. In Sanctus I watch the scaffolding of bodies articulate below the surface, the joints and bones, small and thin and encased in nothingness. In Hammer, she writes that Sanctus “restores the sense of fragility and spirituality to the human body. … We don’t recognize that we are all skeletons with these very fragile yet strong organs encased in a protective framework.” Toward the end of the paragraph she writes, “The body is a miracle.”

Throughout all of this, there are miracles: the bones that hold us together, the bodies that are so fragile yet stand as firmly as mountains for us. Barbara Hammer, you were that for me.

Whitney, this is lovely. Thank you.

Thank you for this. By now I was thinking that AS was not gonna acknowledge Barbara Hammer’s passing

We mentioned it in AAA and on social media the Monday after her passing and noted Whitney was penning an essay for us, and then headlined AAA with her last week. We got you!

Yeah, I was thinking that the mention on AAA was it….

I keep trying and failing to articulate how much this essay means to me, so I’ll just say thank you. <3

A loving tribute. Thank you.

Whitney, this is one of the most powerful, beautiful things I’ve ever read. I feel truly honored to have been able to engage with it. Thank you.

This is so astoundingly lovely. I want to see films how you do, and these films in particular. I love how you pay tribute, remember Anne, and care, highlighting the parts of Barbara you got to see and experience while also seeing her more expansive self. It’s so hard to write an essay that doesn’t reduce the fullness of a large, remarkable life, but yours is just gorgeous. Thank you for writing this!!!!

Beautifully conveyed experience and reflection. Very touching.

I was one of Barbara’s film students in 1978, at her home in Berkeley. A small group of women who were fortunate to have found our leader/model. Her

impact has shaped my life and made me a better teacher (film, pop culture, trouble-making).

And let’s not forget the humor, always bubbling close to the top. Blessings upon her.