all images courtesy of Gay Rodeo History

2024 was a big year for innovation in country music. From the release of Cowboy Carter, Beyoncé’s epic, genre-busting album centering the contributions of Black country artists, to the sapphic cowgirl swagger of Chappell Roan’s new song “The Giver,” contemporary artists are subverting the norms of country western music and claiming space for those underrepresented in the genre.

Both releases sparked cultural debates about what “counts” as commercial country music. In an industry that courts white, straight, and rural listeners, elevating the artistry of Black country musicians and queering the narratives in country lyrics are both political moves designed to disrupt the racist, patriarchal status quo.

For historians Elyssa Ford and Rebecca Scofield, these debates are nothing new. Ford, an Associate Professor of History at Northwest Missouri State University, and Scofield, an Associate Professor of American History at the University of Idaho, both research gender and sexuality in the American West. Their new co-authored book Slapping Leather: Queer Cowfolx at the Gay Rodeo explores how gay rodeos across the U.S. have both celebrated and challenged iconography of the American West to carve out a queer space for LGBTQ folks in the world of rodeo. The book combines extensive archival research with over 70 oral history interviews to look at the gendered, sexual, and racialized dynamics at play in gay rodeo from the 1960s to the 2010s.

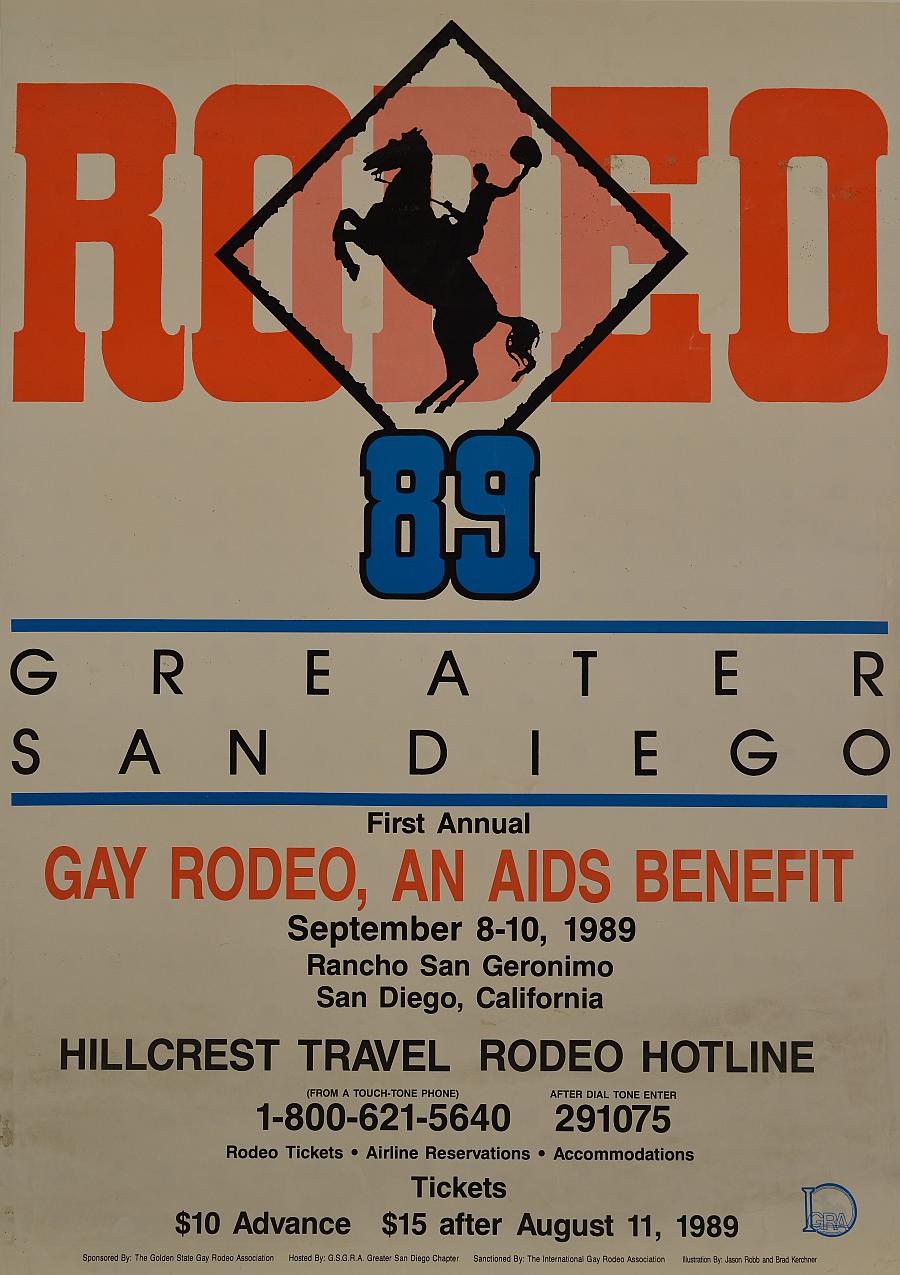

Slapping Leather traces the roots of gay rodeos alongside the development of the International Gay Rodeo Association (IGRA), which helped build, organize, and manage regional gay rodeos as they expanded across the country. The book explores how gay rodeos became increasingly politicized in the 1980s and 1990s, as HIV/AIDS began ravaging LGBTQ communities. Rodeo organizers turned their attention to fundraising efforts to fight the epidemic, facing conservative backlash and public harassment at their events. Scofield and Ford argue that gay rodeo became a “culture of care” that supported sick, dying, and grieving community members in the face of AIDS.

Throughout the book, Ford and Scofield examine “uncomfortable tensions” that queer cowfolx navigated as they sought both to imitate and resist country Western conventions. “Studying gay rodeo provides a look at both the gay male idealization of the cowboy icon and the debates that have developed within this sporting arena as people struggle to embody, rewrite, and redeploy it,” they write. Debates around masculinity in particular have been central to the evolution of gay rodeo over time.

“What makes gay rodeo such an interesting space is [that] it takes all the subtext from a hundred years of Western performance and it makes it text. It really makes people confront these tensions in new and interesting ways,” Scofield shared when I spoke with her and Ford in December. Ford added that gay rodeos “are forced to have those difficult conversations in a way that a lot of other rodeo organizations are not.”

Norms of gender and (hetero)sexuality often go unexamined or unstated in mainstream rodeo. In gay rodeo, however, discussions about masculinity, femininity, and what makes the “ideal cowboy” have been central as organizers have sought to make room for the overlapping and sometimes contradictory politics and identities of their participants.

Several chapters closely examine how the celebration of hegemonic masculinity in gay rodeo has complicated its efforts to include drag performers (the rodeo “royalty”), lesbians, and trans people over the past 50 years. “There are elements of that history that I think need to be examined and questioned and looked at critically,” Ford said.

While neither Ford nor Scofield do rodeo themselves, both attended rodeos as kids growing up in rural Texas and Idaho, respectively. Both believe these insider/outsider dynamics allowed them to approach gay rodeo with a sense of critical generosity. The authors honor gay rodeo for the way it has historically queered images of the American West and staked a claim for LGBTQ folks in rural America, even as it has not always lived up to its inclusive ideals in practice.

In between chapters, colorful oral history vignettes from gay rodeo leaders and participants add nuance and specificity to Ford and Scofield’s historical arguments. The authors draw these vignettes from the Gay Rodeo Oral History Project, which Scofield created and developed after receiving a 2016 grant from the University of Idaho. She mentioned that capturing these stories often meant “meeting this population where they are.”

Scofield elaborated, “There were a lot of aspects about recording at a rodeo that did not follow best practices. They were just like, ‘Nope, you’ve got 10 minutes in between calf roping and chute dogging and I’ll give you what I can.’ And it was always in a barn where it was really loud and people would walk by and chime in!…You get this really aural sense of what it is like to sit on hay bales and interview someone and the atmosphere of the rodeos themselves.”

In addition to the oral histories, research for this book was made possible by the fact that the IGRA has saved much of their materials and donated their archives to the Autry Museum of the American West. Both Ford and Scofield express a deep commitment to supporting gay rodeo organizers in their efforts to preserve and share this history.

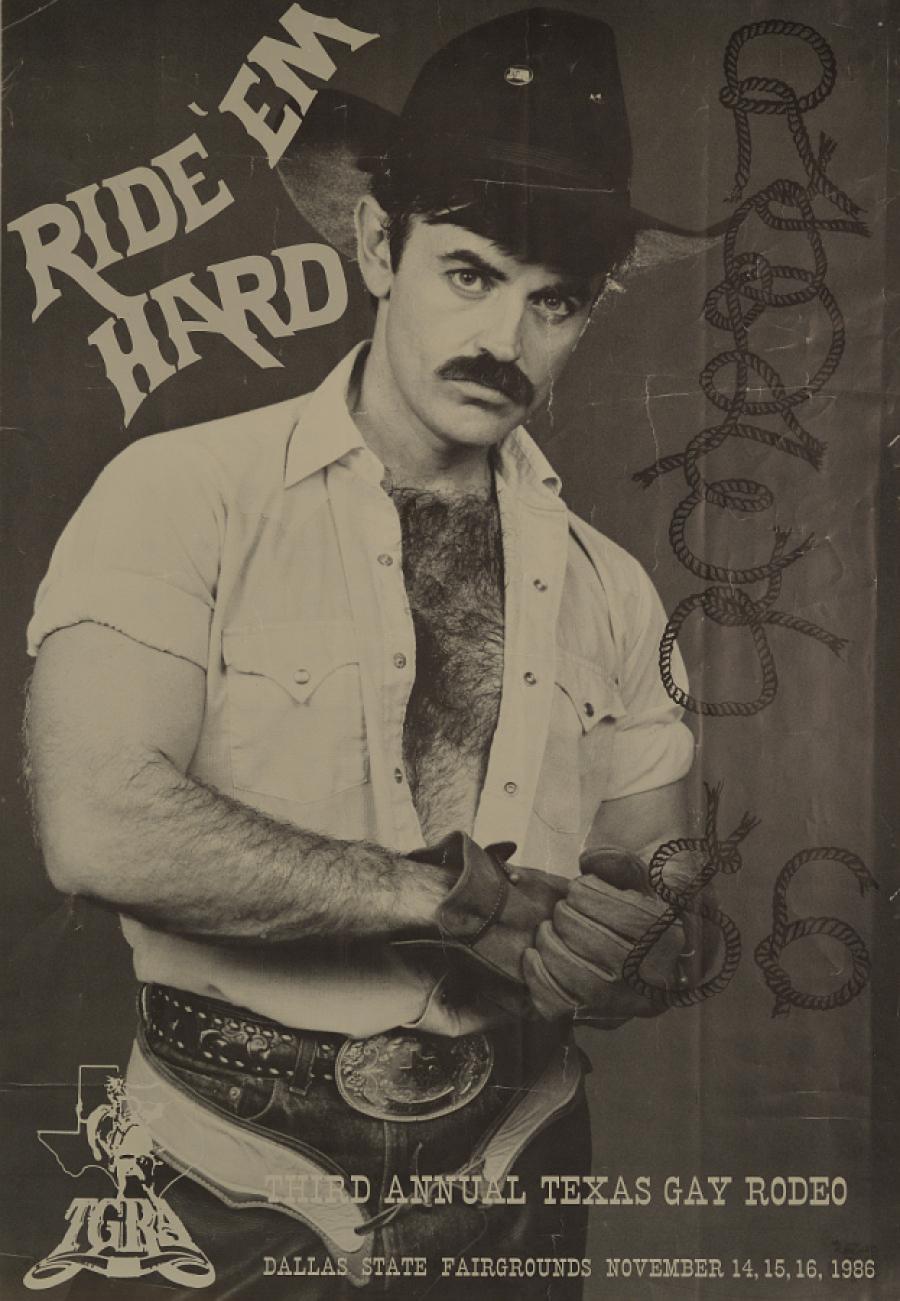

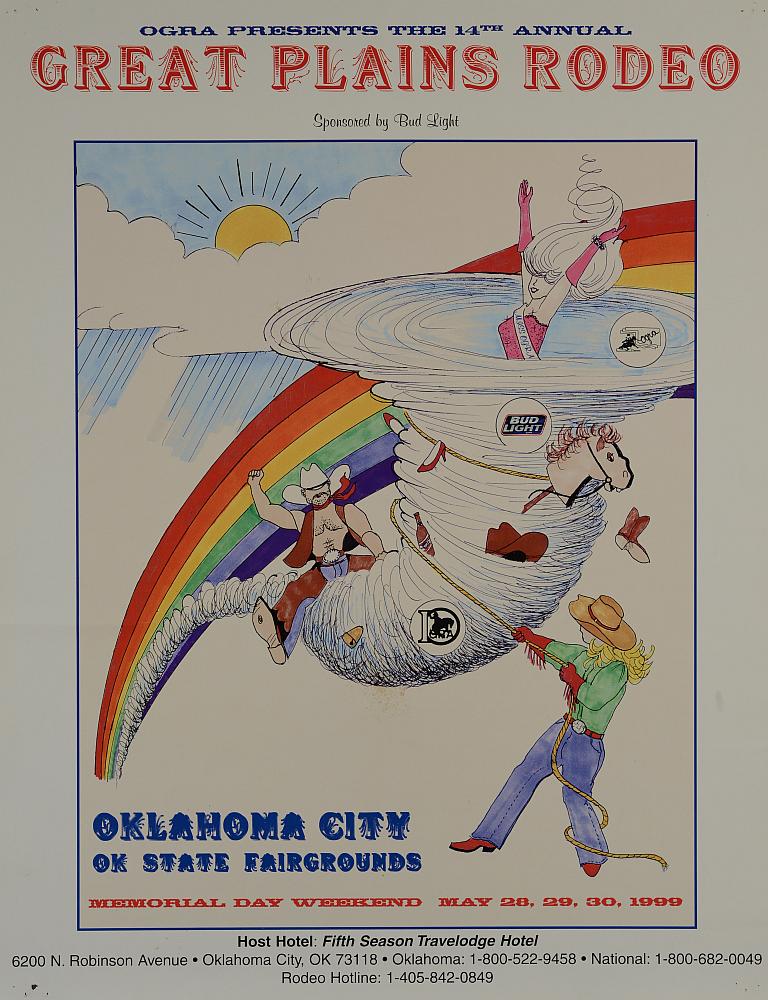

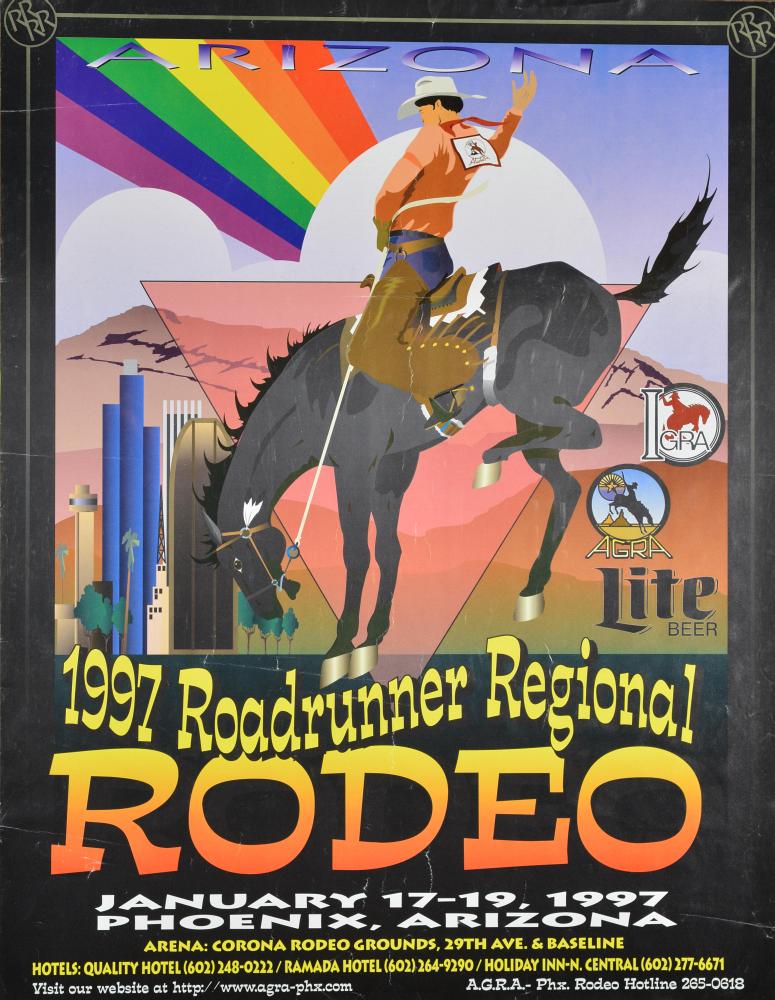

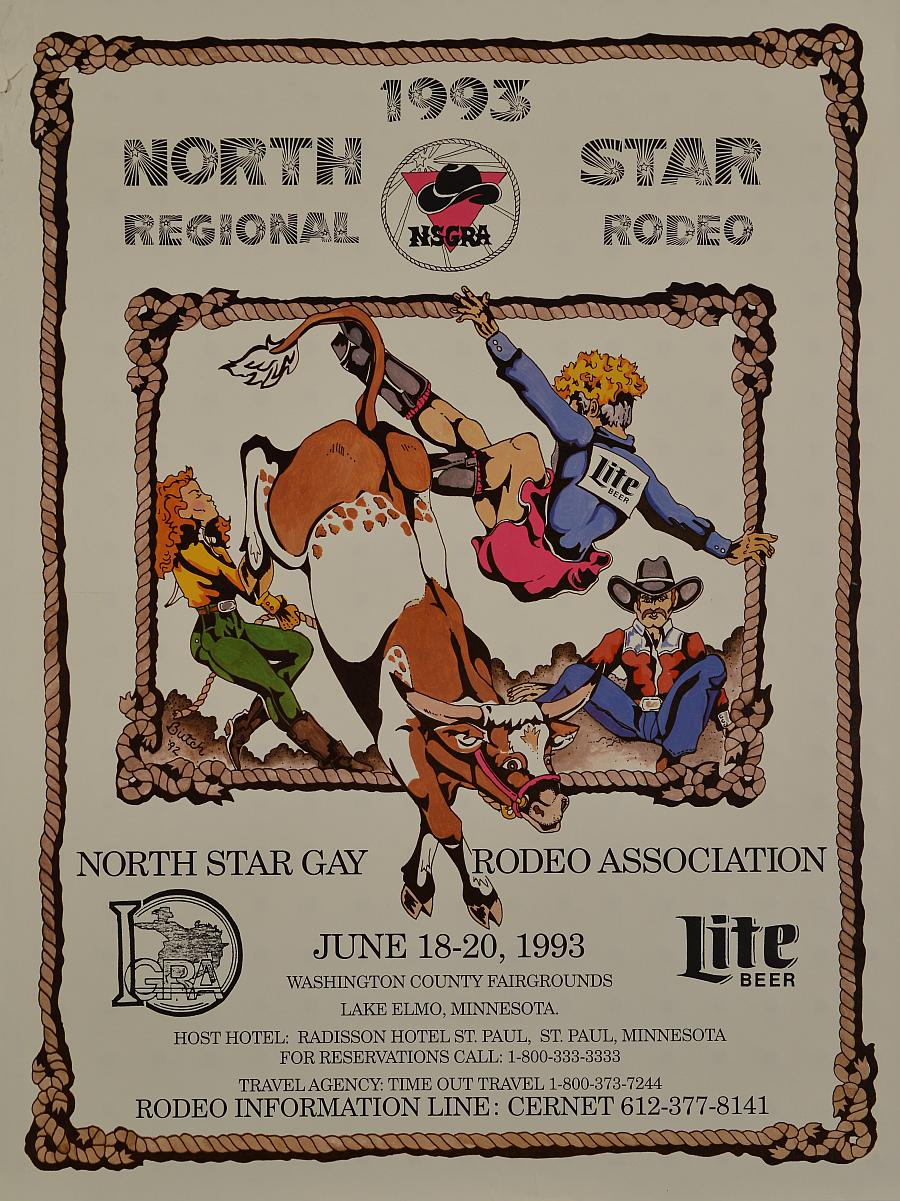

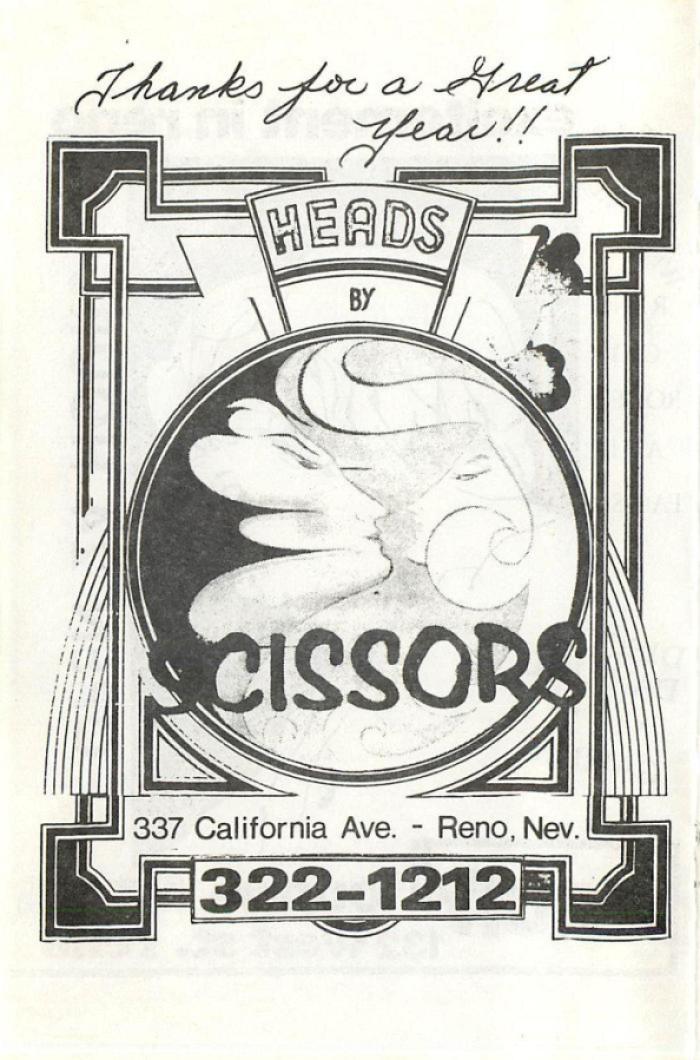

It’s worth paging through Slapping Leather if only to look at the incredible archival images the authors were able to include in the book. Provocative images from rodeo programs help illustrate their arguments about idealized cowboy masculinity and provide readers with raunchy and campy eye candy that demonstrates how gay rodeo historically embraced the specificity of gay sexual subcultures.

While visuals depicting men far outnumber ones depicting women, I was intrigued by an ad for a lesbian bar called Scissors (yes, really!) in a 1979 program in Reno, Nevada. As Ford and Scofield write, lesbian participation in gay rodeos has never reached parity, yet queer women have always played important roles as both organizers and rodeo participants.

Towards the end of the book, Scofield and Ford describe how the number of gay rodeos has steadily decreased since its peak in the 1990s. Increasing costs and diminishing membership have made rodeos difficult to sustain and organize each year. While it is hard to pinpoint exactly why interest in gay rodeos has waned, Scofield and Ford believe gay rodeo will need to evolve in order to attract new and younger participants. As Ford said,

“Gay rodeo wasn’t ever intended to be a remaking of rodeo. It was creating a space where mostly white gay men could be involved in rodeo, but not remake it, because then you wouldn’t be that “true” masculine cowboy, right? … I think [gay rodeo is] increasingly realizing, actually, they’re going to have to remake it in order to survive.”

Ford and Scofield consider that remaking gay rodeo might mean embracing more fluidity in its understanding of gender. As in many sports, gender binaries structure various gay rodeo events. Getting rid of gendered categories altogether might create more space for younger and more gender nonconforming queer and trans folks to join and compete.

Slapping Leather addresses how the idealized white masculine cowboy has always been a myth, one that erases long histories of Indigenous and Black life in the American West and ignores the involvement of women in country western culture. Queer cowfolx have reworked these myths to center LGBTQ community and sexuality in the world of rodeo. In doing so, Scofield and Ford write how gay rodeoers have “imploded the rural and urban divides that have structured thinking about liberal and conservative politics and queer safety and belonging for the past century.” As queer cowfolx “created spaces that could exist beyond the imagined restraints of both the rural and the urban,” they complicated our assumptions about what it means to be LGBTQ in rural America.

Perhaps the time is ripe for rethinking and remaking the American cowboy, as Beyoncé and Chappell Roan’s latest musical projects suggest. In a time of renewed and relentless legislative attacks on LGBTQ lives, particularly across the American West, Midwest, and South, we might need a gay rodeo renaissance: one that rejects these myths and embraces the vast, diverse queerness of the American West, once and for all.

Be aware that nearly every animal welfare organization on Planet Earth condemns rodeo due to its inherent cruelty. Plus the fact that it’s mostly bogus hype, a macho exercise in DOMINATION. Real working cowboys/girls never routinely rode bulls, or rode bareback, or wrestled steers, or practiced calf roping (terrified BABIES!) as a timed event….Rodeo is not a true “sport”–that term denotes willing, equally-matched participants. Rodeo does not qualify.

As a gay man, I find it sad that gay people–of all people–would take part in this abuse. Have we learned so little from our own long history of abuse? Many gay rodeo participants don’t even know how to ride a horse! Hence the nonsensical “wild cow drag,” “sheep/goat dressing,” et al. There are some 2,000 rodeos held annually in the U.S. (plus many hundred charreadas), the majority of which don’t even require on-site veterinarians. The PRCA has had an on-site vet requirement only since 1996, after FIVE animals were killed at the 1995 California Rodeo/Salinas. It all needs to end.

The United Kingdom (England, Scotland, Wales) outlawed all of rodeo back in 1934, soon followed by the Netherlands. Can the U.S. be far behind? Legislation is in order. In the interim, BOYCOTT ALL RODEOS, THEIR ADVERTISERS AND CORPORATE SPONSORS. Follow the money.

x

Eric Mills, coordinator

ACTION FOR ANIMALS

Oakland

P.S. – See prize-winning rodeo documentary, “BUCKING TRADITION” – http://www.buckingtradition.com

Rodeo is animal abuse for profit and entertainment. It needs to end.

It is really sad to have gay people promote this abuse. They should understand oppression and what it feels like to be treated as “other”. I’m a lesbian and this promotion of gay rodeo is really disturbing to me. Please look at rodeo from the point of view of the animals. Use your empathy. We should be eliminating rodeos.

No people I know would subject their dogs to what we do to the animals in a rodeo. This cruel “entertainment“ should appall everyone who calls himself an animal lover.

Looks like we’re getting brigaded. Oh, good.

Any self-respecting person—gay or straight—should be appalled by the gay rodeo.

Gay rodeo rules do not protect animals from abuse—animals are still whipped, kicked, prodded, and slammed into the ground. Even when animals aren’t injured (and they are often are), they still suffer from fear and pain involved in the events, and the stress of travel in crowded, ill-ventilated trucks. They are used time and again before their bruised and battered bodies are shipped to the slaughterhouse.

I appreciate the above comments about animal rights and gay rodeo. I wanted to chime in to add that the authors of the book do explore complex issues and critiques of rodeo, including allegations of animal abuse. I didn’t write about that in this short piece, but I recommend checking out the book for more info. It does a wonderful job discussing and exploring these aspects of LGBTQ history and culture.

Thanks Lauren. I really enjoyed reading this piece. I didn’t know anything about gay rodeo (and I all I “know” about gay cowboys comes from reading queer romance, so it’s nice to get a more accurate picture).

Dr. Robert Bay from Colorado autopsied roping calves and found hemorrhages, torn muscles, torn ligaments, damage to the trachea, damage to the throat and damage to the thyroid. These calves never get a chance to heal before they are used again. Calves roped repeatedly in the practice pens suffer constant pain and injuries to their necks. Meat inspectors including Drs. Haber and Fetzner who processed rodeo animals found broken bones, ruptured internal organs, massive amounts of blood in the abdomen from ruptured blood vessels and damage to the ligamentum nuchae that holds the neck to the rest of the spinal column.

Dr. C. G. Haber, a veterinarian with thirty years of experience as a USDA meat inspector, stated “The rodeo folks send their animals to the packing houses where I have seen cattle so extensively bruised that the only areas in which the skin was attached was the head, neck, legs, and belly. I have seen animals with six to eight ribs broken from the spine and at times puncturing the lungs. I have seen as much as two and three gallons of free blood accumulated under the detached skin.” This information is science-based. It is time to end rodeo.