As long as people have been people, we have sought places of belonging and community. And as long as queer people have been queer, we have found those places pertinent to our survival.

A little of my own background: when I’m not changing the online queer literary scene on Autostraddle with such articles as Bottoms Characters Ranked by Whether or Not They’d Be Bottoms, I am a poet. From 2019 to 2022, I was at the University of Texas at Austin, working towards my MFA. Despite emotional and personal hardships experienced during those years (some created and/or exacerbated by COVID), I regard that time as some of the most creatively invigorating and emotionally beautiful years of my life. As artists, the opportunity to spend your time focused primarily on creating art and communing with other artists is like nothing else. I was very lucky to get into the New Writers Project, a fully funded program that supplements students with teaching assistantship stipends. It wasn’t much, and certainly not in an expensive city like Austin, but I was and continue to be so grateful for that chance to dedicate three years of my life to my poetry and writing.

I met one of my best friends, the queer poet Rob Macaisa Colgate, there, and much of our time in Austin together was spent in one another’s “COVID bubble.” We had masked Drag Race viewing parties of two, wrote poetry together on his porch, often ending our nights by blasting music as we danced around the nearby intramural fields. Before the pandemic hit, and after vaccinations and masked gatherings were tentatively beginning, I got to spend time with other classmates from a wide range of genres and life experiences. While the act of writing can often feel solitary, the truth is almost nobody can write great work without the help of others. Workshops and classes that encouraged sharing work and discussions were as crucial as parties where we drank and reveled in one another’s presence.

Many of the creative communities and partnerships in the world of the arts, like other MFA programs, have had institutional backing, but many others have been formed through the mere desire for human connection that comes from people chance meeting and thinking, “we should do something about this energy.”

Juno Rosenhaus, photographer and visual artist, has had a vision of creating a queer arts space like that for a long time. Coming to Philadelphia in 2018 after her retirement, Rosenhaus had the plan in motion already to find a physical space where she could carry out the mission of curating an artistic residency and community space for queer people — specifically for older lesbian artists.

“It’s a bit of a cliche that life ends at 40 — fuck that,” Rosenhaus says. “The older you get, the more invisible you are. And being queer, being lesbian, you’re already marginalized and struggling to have people see you…I want to highlight that margin; I want to live in that margin.”

Having grown up in north Jersey, then spending 30 years in the Bay Area raising her son and working a corporate medical job, she knew the next chapter of her life should prioritize this mission. She chose Philadelphia in part because she wanted to return to her East Coast routes. But mostly, it was becausePhilly’s prioritization of community and access surpassed so many other cities considered for the project. In 2020, much sooner than she expected, Rosenhaus found a house in the Mantua neighborhood, and began what is four years later known as Dyke+ ArtHaus.

Literary salons, especially those for queer writers, are not a thing of the past, but without their history, we would not have them in the capacity we do today. In conversation with Rosenhaus, I am personally reminded of Natalie Clifford Barney. Barney, an expatriate living in France in the 1900s, was known for her literary salons that prioritized female writers (and queer writers). For those who have read Radclyffe Hall’s 1928 lesbian epic The Well of Loneliness, Barney will be easily recognized in the character of Valérie Seymour, a courageous and ethereal hostess whose open sexuality contrasts immediately with the protagonist Stephen Gordon’s self-loathing. Hosting these salons at the infamous 20 Rue Jacob in Paris, Barney created a reputation for herself as a curator of great art, as well as a scandalous celebrity no stranger to sexual intrigue for her unabashed lesbianism. Gertrude Stein, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Edna St. Vincent Millay, and other literary icons all made appearances at her salons.

However, Barney is a complicated figure. Despite the great advancements she made for women and lesbian artists through her salon and her unrelenting sexual expression, she espoused anti-Semitic views during World War II (despite changing such views by the end of the war) and was close friends with the writer Ezra Pound, a virulent pro-fascist of Mussolini’s Italy. Likewise, her salons were clearly targeted towards a supposed upper echelon of literary figures — those who had access to such spaces due to generational wealth. Rosenhaus’ approach to community in the present, in contrast, defies this idea of financial access barriers as an inevitability of such artistic colonies.

“The first barrier is financial access, and I try to work against it in any way I can,” she says. “This pay-to-play stuff is so stifling to so many people, and sure, you need some money to cover the backend of costs, but otherwise you’re just making money off of artists.” The residency, marketed as pay-what-you-want, never prioritizes profit over people, according to Rosenhaus. The space’s financial access is intentional, as well as the aesthetic of the space. Available on the website are photographs of the space, which match Rosenhaus’ description of being inviting and comfortable: an abundance of chairs and desks, vibrant yellow and calm blue walls, art by lesbian artists lining every nook and cranny. The place truly gives the impression of a home, a home where anyone can come for their art and for connection.

“The richest thing is being in that space together,” Rosenhaus says, “It’s the energy and taking away of barriers.”

In the U.S. during the mid-to-late 20th century, lesbian art boomed in its connection to activism. The lesbian periodical became its own genre, from On Our Backs; to Common Lives, Lesbian Lives, Sinister Wisdom; to The Ladder. These periodicals worked as educational pamphlets, as well as tethers for rural lesbians to a sense of self and community beyond their access. The movement of lesbian feminism — in reaction to the women’s movement’s purposeful exclusion of lesbians — relied heavily on literature of all shapes and sizes to increase understanding. The 1970s saw luminaries like Audre Lorde, Gloria Anzaldúa, Adrienne Rich, Rita Mae Brown, Barbara Smith, and others, engage with one another on the largest issues of the lesbian movement at the time: gender, race, war, pornography, socialism, et cetera. A lesbian-feminist network of indie publishing boomed as well, much of which is historicized in Kristen Hogan’s The Feminist Bookstore Movement: Lesbian Antiracism and Feminist Accountability. These lesbians, their practices, and their personal and political motivations were by no means a monolith, but certainly their prominence suggests an uprising in lesbian voices pertinent to the movements of the 1960s and ’70s that cannot be ignored.

This level of art intermingling with activism is also a part of Dyke+ ArtHaus’ creed. “A lot of the baseline for what I do is asking myself: How does this support a feminist, anti-racist mission right off the top? That’s always first,” Rosenhaus says. She emphasizes that creating a space for all lesbians — regardless of age, gender, race, socioeconomic status — is crucial.

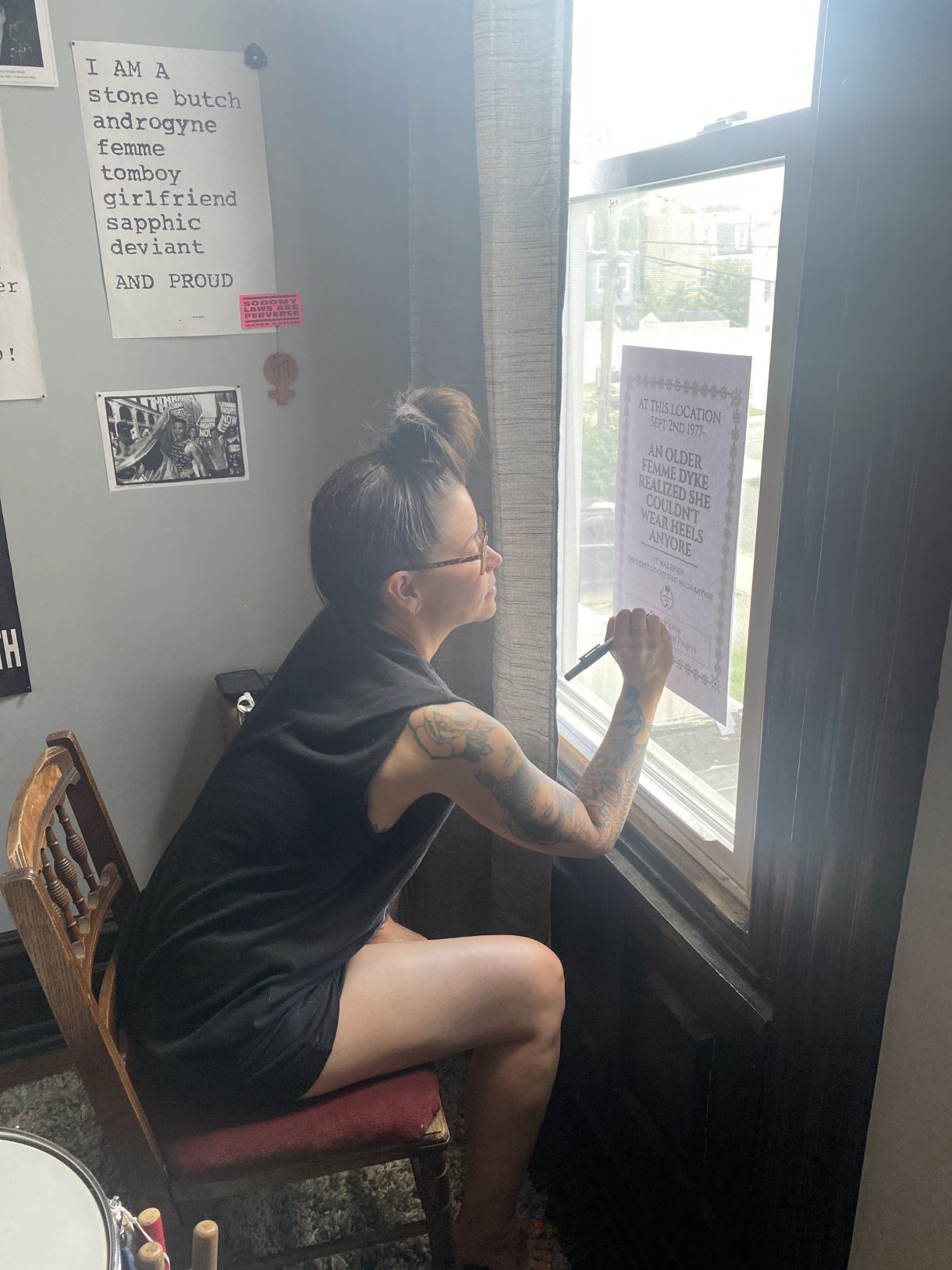

In addition to individuals, there were (and still are) organizations dedicated to lesbian activism. One such group Rosenhaus quotes both on her website and in our interview. The Lesbian Avengers, credited with creating the first Dyke March, were founded in NYC in 1992. Part of their activism — aside from fire-eating and anti-Prop 8 demonstrations — included wheatpasting. A quote from the Lesbian Avengers on Dyke+ ArtHaus’ website says that wheatpasting “is the activist term for adhering flat art onto outdoor establishments so that the unsuspecting community becomes a captive audience.” This leads directly into Dyke+ ArtHaus’ most recent project: the Lesbian Mapping Project.

A collaboration between Rosenhaus and Beth Schindler (also featured in Texas’ DIY Parties Are Creating Spaces for Lesbians From Scratch) began this past summer The two utilized the age-old activist method of wheatpasting to plaster Philadelphia with posters documenting lesbian history in the area. But rather than immortalizing activist movements or tragedies, the posters focus on joy and self-discovery, moments like “a dozen lesbians their exes narrowly missed running into each other,” or “a dyke saw the lights from the dancefloor gleaming through the peach fuzz on her lover’s body.”

“Beth came up with this idea of ‘what happened here,’ and what I liked about it was it wasn’t all about grief and fucked-up political things that continue to happen,” Rosenahus says. “It was about fun, ironic things, things that are ridiculous, things that are profound as well…Telling the world ‘this happened here, dykes live here,’ and that’s always been a thing I’ve wanted to do. Fuck you and your lesbophobia!”

The invention of the project is not meant to be attributed to Schindler and Rosenhaus only — the Dyke+ ArtHaus website provides a blank template and instructions on how to create your own in your city. To memorialize the history of lesbians across cities is part of the project’s mission, and it has already spread to NYC. In addition to the Lesbian Mapping Project, other projects have included the Poetic Ritual Playground — a collaborative poetry project conceived of by Dina Ara Fulconis and Forest Smotrich-Barr — and a personal collaborative co-curation between Rosenhaus and photographer Lola Flash at the queer bookstore Bureau of General Services Queer Division, entitled “Dyke+ ArtHaus Visits the Bureau,” the longest-running exhibit of “Dyke artists over 50, that we know of.”

It is clear Dyke+ ArtHaus joins a lineage of lesbian and queer artist spaces that prioritize community over profit, collaboration over self. Now, like any time in history as a queer person, such priorities are crucial — even Autostraddle exists among this lineage. While we as artists live in a capitalist world and must make some profit to survive, it is the kindness and activism of people like Rosenhaus, Schindler, and other lesbians of yore, that remind us why we make art in the first place: because it reminds us we are alive.

As Rosenhaus puts it: “Making art together is one of the richest things you can do.”

What wonderful context to bring the Dyke+ ArtHaus into! We all need space to connect and collaborate, and this space is special.