I was 15 years old, walking into the Oxford Street Topshop — wearing black skinny jeans, a skintight white tank top with visible neon bra straps, tie-dye Converse and a vintage army jacket from Camden Market — when a breathless stranger tapped me on the shoulder and asked me if I’d ever considered modeling.

This was odd, but not something I was completely unprepared for.

the author as a child

I was four when I started dancing. I grew up doing theatre school, acting and singing. I loved being on stage. I was the one who’d bully the other kids into putting on plays for the parents on group holidays, taking VHS footage of myself as soon as I could operate a camera.

I became fixated with fashion pretty early on, often inspired by the Y2K-era music videos I’d spend hours watching on Saturday daytime television. The first thing I ever saved my £1-a-week pocket money for was a one-shoulder glittery purple top from NEXT — a strong nod to my nascent bisexuality, sartorial showiness and enduring obsession with pop stars.

I was 12 when my family emigrated from the reserved, quaint English countryside to the sundrenched coast of South Africa. We’d been going to Cape Town on holiday for most of my life, but moving was different than visiting. I love Cape Town deeply, and in many ways consider it home, but moving at that age was a challenge. My unformed personal identity melted as the markers I’d begun to orient myself around completely shifted. In retrospect it was ridiculous that I felt so unhappy when my life was idyllic in so many other ways, but then again, I was 12.

Paging through fashion magazines and scrolling through Tumblr became the antidote to the loss of control I was feeling. I was captivated by this aspirational, escapist lifestyle, and by the fantasy of the fashion shoots I memorized. I was obsessed with curating an aesthetic representation of my emotions on Tumblr — combining Lana Del Rey lyrics and Sylvia Plath poems with moody imagery and heavily reblogged GIFs. I thought I was seeing a world that was an antidote to the mounting inner discomfort of my adolescent life.

Like most teenagers, I hated and had become bewildered by the body I inhabited, determined as it was to be a site of unwanted attention and speculation. I wasn’t considered one of the “hot girls” at school. I was a tomboy who wore oversized band t-shirts and ripped bongs as my top party trick. But in the wider world, the world that I felt less at home in and increasingly at odds with, things had been shifting for a while.

I was 13 years old, at the mall, when another girl first pointed out, “people keep staring at you.” I fielded catcalls every time I went outside in shorts. I was 14 when a man old enough to have a car and several tattoos pulled up alongside me and asked for my number. When I declined, he asked me for a kiss. A stranger in a club offered to pay me to have sex with him. A guy I thought was my friend sexually assaulted me at a house party. I didn’t tell anyone. He and my best friend ended up dating for a year.

At a time when my own sexuality and desires were so vague to me, I was constantly being sexualized by others.

All of this had made me cold and standoffish to people I didn’t know. I punished myself with bouts of starvation and self-harm. I was afraid that these physical changes would continue to snowball into an instability that would dominate my rapidly approaching adult life. My body and my selfhood drifted further from each other every day, transforming outside of my permission, and I struggled to hold on, fumbling to hold on to my shadow.

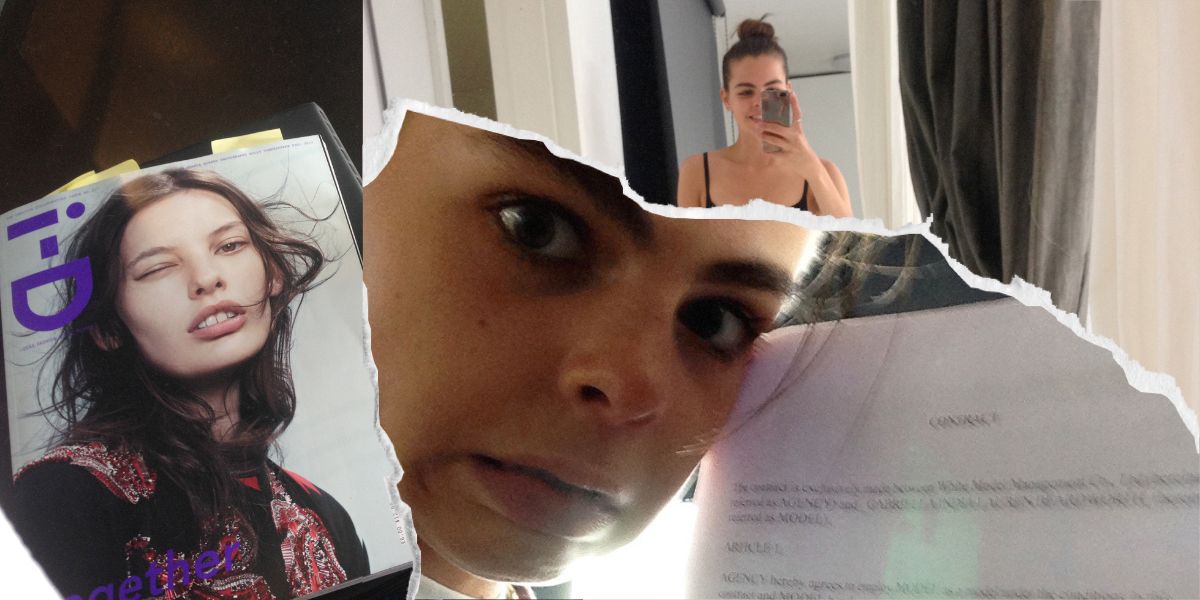

By the time I was stopped by a scout in Topshop, I’d already spent years tearing out the pages of i-D, Dazed & Confused and Vogue. My bedroom walls were plastered with photos of fashion shoots, designer brand adverts, celebrities coked up at fashion week parties and models wearing American Apparel hot pants.

So I’d already realized, like so many of us do, that my body was only partially my own.

Pursuing modelling seemed like a way to feel a sense of control over a space that had become uncontrollable, or at least something a lot sexier than drinking cheap vodka until I blacked out at house parties.

Fashion magazines showed me that it was possible to build a career — a world, even — where you could always be making things. You could actually have a life where you were creating new worlds and escaping into alternate universes every day.

In the images I saw in magazines and online, the women seemed infallible and intimidating. Captured in a photograph, a moment became untouchable. It seemed like both a gilded cage and a suit of armor; trapping and protective in equal measure.

So there were a lot of reasons I said yes to modelling — I’d always been a ‘natural’ in front of the camera, I’d grown up performing, I loved fashion and art, and I was thrilled and terrified to embark on something beyond a predestined life path. It was aspirational, and glamorous. But above all I craved a space where I could gain power over my dispossessed body.

I was naive and all wrong about what modelling would entail, of course, naive to think I could shape it more than it could shape me. But then again, I was 15.

My journey in ‘the industry’ began tentatively with awkward test shoots and corny campaigns before progressing to full-time after finishing school.

Three days after my last exam and mere weeks after turning 18, I signed my first modelling contract, landed in Tokyo and went straight from the airport to a casting in the same clothes I’d travelled in. I booked that first job, was handed a flip phone (foreigners couldn’t get a SIM in Japan then), a printed map, $100 in yen as my weekly pocket money, and told that I’d be picked up at 4am the next morning to shoot the campaign. I was contracted to reside and work there for the next three months.

I lived in a tiny but comfortable room, sharing a toilet, kitchenette, minifridge and bedroom with a roommate named Sharnay, a happy-go-lucky fairy sort of girl with long blonde hair and a breathy voice. We had this plasticky sliding door that led to a narrow balconette that we’d drape ourselves over, smoking the cigarettes we got handed at our favorite clubs, absorbing the humming aura of the city. Sharnay never asked me where I was going or what I was doing. She didn’t seem unsettled by my intensity but also didn’t really care to understand it.

I remember feeling a revolutionary freedom on that first trip. I spent my own money for the first time ever, on anything I wanted — in 24-hour discount stores like Don Quijote, in Tokyo’s otherworldly vintage shops. I’d wander around alone, going on solitary excursions to distant parts of the city, visiting holy temples and flea markets, losing myself in complete unfamiliarity.

I felt like I’d been given the key to another universe, far away from the painful and embarrassing memories of high school. I felt boundless freedom.

Our agents ferried the models around in vans, and we bonded there, or in the corridors of our apartment building or in the hallways of the castings where we’d sometimes be waiting for hours to be seen. These bonds were predicated on shared experiences rather than true commonalities, spaces that were as beautiful as they were fleeting.

I went out almost every night to clubs in the seedy Roppongi neighbourhood, where all my drinks and food would be free. The clubs were filled with models from every agency in town, doing shots as the venues capitalised on the free floor fillers. Promoters would invite us en masse to lavish all-expenses-paid for dinners at Michelin starred restaurants, covered by mysterious businessmen who had no issue picking up extortionate tabs in exchange for being surrounded by teenage girls. The drinking age was 20 but that was never an issue, even for the girls as young as 15, who often barely spoke English. I had the luxury of being in the industry by choice, but at least half of the models I encountered were working in Japan to make money to support their families back home.

As my career progressed, the elements of it that made me uneasy and its negative impact on my mental health multiplied.

I have an addictive personality, and I was biting my nails down to the quick as a “fresh face,” eager to book the best jobs — every time I was picked to work with a big photographer, be shot for a brand that was a household name, or commanded a big rate, I’d get a rush not unlike that of a gambler’s.

Whenever I landed in a new city or worked with a new agency, they’d start by taking my measurements and (sometimes, like in Tokyo) weighing me. Contracts prohibited changing my appearance – no haircuts, no acne, no gaining weight. My agents sometimes felt like my surrogate parents, but they also took as much as 70% of what I was paid for my work.

When you’re chosen to be a model you’re seen as mature enough to be able to travel alone and work full time, but often not human enough to be valued beyond your perceived surface level value. Although I was 18 and technically considered a legally consenting adult, I looked years younger. It’s unsettling to revisit photos from that era, like a Sydney shoot when I was 18 where, even with makeup and hair, I look about 16. I’m topless in half of them. I was surrounded by blurred lines, whispers about predatory agents and clients, sexual harrasment, even sexual assault.

My mental health had been rocky since my early teens, waves of mania intermingled with bouts of depression. At times I hated every inch of my body, finding flaws that I would carve out of thin air. Other times, the flaws were pointed out to me as I was picked apart in front of a team of people, like the photographer who told me I had ugly hands at my first editorial photoshoot, leading me to a bathroom panic attack.

The lows may have been low, but the highs were very high.

When things were good, when work was good — in those moments I could feel like I owned the world. I was making money, I was seeing new places, I was on billboards in Tokyo or drinking champagne on a yacht in Sydney, going straight from the afterparty to another shoot. I was living a life many could only dream of while my old classmates were at college, on a gap year or working for an entry-level wage.

When the people defining mainstream beauty tell you that you’re beautiful, the validation is affirming and addictive. Especially when you’re a teenage girl. It’s an unparalleled ego boost. I walked catwalks for designers whose clothes I adored, hand selected from hundreds of girls with similar desires. I was invited to the parties filled with the same people I’d poured over in magazine photos. I got to meet and work with industry icons that I’d looked up to for years. I was shot by my favorite photographer of all time after he approached me at a party.

Eventually, the validation wasn’t enough to replenish the depletion of what it cost to receive it.

I was big in Japan. After the first two years of modelling stints there, I started questioning what my body was bringing to this space. Things I’d been brushing off began to irk me more consistently. What did I, a white girl, mean in this country where the people buying what I was selling don’t look like me, and shouldn’t want to? These thoughts plagued me, but I’d push them down, reminding myself that this was my dream job — and also the only job I’d ever had. Where could I go from here?

The persistent niggling eventually led me to question my physical form — its validity, its privileges — in ways I couldn’t have predicted when my career began.

Despite how hard I tried to curate an enigmatic persona, I often longed for the things I’d once shunned as boring: familiarity, a regular routine, my parents. Every rejection from a job I’d been close to booking was, to me, proof that I wasn’t good enough. I was trying to match up to the idea of the “model” I thought an agent or client would want, and convincing myself that was who I wanted to be.

I felt increasingly trapped in a static identity. I was strongly discouraged from changing my appearance, so I kept my long brown hair. I wasn’t allowed to change my body shape, so I rationalized restrictive eating as part of my job. My personality became part of why people liked working with me, and I felt good about that — it made me feel like more than just a model. But it also made being more than just a model even more personal.

I moved to London and I fell in love with my first girlfriend. We were a gorgeous couple and that became a thing — us, together, working. A first queer relationship is a life changing experience. Mine became intertwined with my job. On a shoot for a Pride campaign, the same niggling questions about what I represented came up again. At the time I barely knew anything about what it meant to be queer aside from the fact that I was in love with a girl. I hadn’t had to fight with my family to live like this, or struggle with so many of the challenges that the majority of people face regarding identity and sexuality. I felt like I was taking something away from someone who might deserve it more and I hated having our relationship so swiftly commodified.

Olivia Laing writes, “to be born at all is to be situated in a network of relations with other people… We’re all stuck in our bodies, meaning stuck inside a grid of conflicting ideas about what those bodies mean, what they’re capable of and what they’re allowed or forbidden to do.”

One of the reasons that humans are such a successful species is that we are highly adaptable. We understand how to read a situation and change our behaviors to best benefit from it. Our brains regulate our responses based on relativity, meaning that things that would seem strange, given enough time, become totally normal. It was easy for the unsettling world of modeling to gradually feel sane, even regular.

At the onset of the pandemic, I ended up living at home for the first time since I was a teenager. I was able to be honest with myself for the first time since I’d started modeling. Who could I become if I let go of the narratives I’d so long held on to that no longer served me? What if I let myself change my appearance, running the risk of not seeming so attractive? What happened if I dressed how I felt truly comfortable? I cut my hair short and dyed it red. I got tattoos.

I’d tried on so many versions of myself that were meant to be the right fit, yet none had been the right one for me. I needed to find my own identity. I was terrified to let myself be myself. It felt like I was walking away from everything that seemed safe.

I started studying, finding a sense of accomplishment and truth outside of myself through academia. I started letting my guard down and rediscovered the part of myself that craved learning and was deeply fulfilled by knowledge. I re-learned what it felt like to have a sense of accomplishment that came from linear effort. I discovered feminist and queer literature, ways of understanding the power structures that dictated the systems I had felt so trapped and isolated within. I came to understand that it was all about perception and illusion. That I could try something else, and that there was somewhere else to exist.

I’d signed with an agency in America the week before the pandemic took hold, but I’d not been able to enter the country for two years. When I finally returned to LA, I didn’t work once. My look wasn’t what they wanted. My London agency lost enthusiasm for me. But I couldn’t keep treating myself with the harshness and coldness that maintaining a certain image required. I left my agency.

I didn’t go into modelling with sinister intentions. I don’t think any of us did, really. There was power to be gained, but power over what? And at what cost? I was wrong about modelling being a way to gain control over my body and my image — I had less of that than ever. I started to feel like I’d just become part of the same machine that had harmed me — and probably you— growing up.

Things often felt like they were happening to me instead of coming from me. I was growing up, society was shifting, my career plowed forward. What became clear to me amid all of that is that I hadn’t really been taught a way to understand the world around me. I know I’m not alone in the helplessness, desperation and apathy I sunk into. We all feel at once overwhelmed and disconnected; part of an inescapable interconnected mess, yet alone and left to fend for ourselves.

Young and naïve, I looked towards magazines, media and the Internet to tell me about the world. I imagined what it might look like when I grew up and became a part of it, not realizing how literal or destructive that aspiration would become.

As an adult, I’ve looked towards philosophy, feminism, modernist discourse and queer theory. I found books that helped me unwind the knots I’d bound myself into, ways to re-situate and negotiate my understanding of my place in the world and the world’s meaning to me.

I’m focused on other work now and really didn’t expect to model again. However, against everything I had chosen to believe or been told, modelling now feels good in a way it never did before. I recently walked in a show in London Fashion Week for a brand I’d always wanted to work for, creating and performing a movement piece with the designer that explored feminine desire, rage and rebirth. I starred in a music video, dancing around in the outfit I had worn to the club the previous weekend. I am the face of a beauty brand centering inclusivity, diversity and self-care, with my bald little face plastered across two cities I love and that have shaped me, London and Berlin.

As I walk around the city, I occasionally encounter photos of myself plastered on the wall for a beauty brand. My hair is buzzed and bleached, and the campaign poster images reflect someone I actually know.

We’re all stuck in our bodies and a grid of conflicting ideas. All we can do is bear witness to the body we have, and choose how to act from that place. Where that turns out to be, exactly, might surprise you.

I’ll be honest: I was skeptical about this essay. It didn’t seem like a story that would matter to me or draw me in. But I have found myself nodding along, highlighting lines to revisit later, looking up the Olivia Lang quote, wanting to know more about you and your life. These are feelings I have felt too, like feeling that you don’t have control over your body and then trying to get that control back through ways that end up not satisfying that itch. Beautiful work.

came here to say something similar. came into the essay skeptical, but i was blown away by what i read.

it just goes to show you never know what is going on with somebody behind the curtain

Not on this level, but had a similar experience with my first queer relationship being commodified. What a head trip! I have always had a hard time with caring too much what other people think, even what friends or family would think if we broke up. Having to also consider my career in those cases, made the relationship last so much longer than it should have. Really enjoyed this.

gorgeous words, gorgeous pictures.