Last time on Lesbian and Bisexual Women Who Were Obsessed with Their Dogs, we learned many lessons from our queer ancestors about how best to incorporate your canine companions in to your lifestyle. There was a big yes to fashion photoshoots, European travel and fleeing the patriarchy; a big no to stage plays, and a big WTF to worshipping your dog as the reincarnation of Christ. Also if you haven’t written your dog’s-eye-view novel yet, you need to get on that right away.

I’m sure at least one reader has been panting with anticipation about what further revelations lurk in our woefully unexplored queer pupper past. Find out literally right now, as we continue our historical adventures with gal’s best pal!

Emily Dickinson

Emily Dickinson, America’s favourite depressive poet, came from a wealthy, well-educated family in 19th century Amherst, Massachusetts. Despite her strong intellect and probably because of the mental illnesses that would bring her great suffering throughout her life, Emily only made it partway through her schooling at Mount Holyoke Female Seminary and returned home to teenage years of increasing isolation.

Perhaps observant of her lack of companionship, Emily’s dad Edward gave her a brown Newfoundland puppy in 1849. Emily named him Carlo, after a dog in Jane Eyre, and he quickly grew to about three times the size of the diminutive young poet, a sight that amused visitors. Dickinson’s first ever published work in the Amherst College paper in 1850 also contains her first written reference to Carlo, as part of a lengthy and accomplished metaphor from which I have conveniently extracted just the dog parts:

“If it was my Carlo now! The Dog is the noblest work of Art, sir. I may safely say the noblest — his mistress’s rights he doth defend — although it bring him to his end — although to death it doth him send!”

Sadly, no pictures of Carlo exist, but here is an artist’s impression of a Newfoundland from 1858

It was around this time that Emily forged another close bond, with Susan Gilbert, a student her own age who shared a lot of her interests, including despair about their lot in life as housewives-to-be and the dislike of household chores (although Emily was actually a champion baker). Susan’s erudition and passion for literature would inspire over 300 letters from Emily over the course of her life, far more than to any other correspondent, and included many of Emily’s most famous poems. Of course, scholars argue over whether the nature of their attachment progressed from friendship to romantic friendship, or even something more, but we can all use our rational gay judgement to reach the correct conclusion. Whatever their relationship, it didn’t stop Susan going on to marry Emily’s elder brother, Austen.

“Oh Susie, I often think that I will try to tell you how very dear you are, and how I’m watching for you, but the words wont come, tho’ the tears will, and I sit down disappointed — yet darling, you know it all — then why do I seek to tell you? I do not know; in thinking of those I love, my reason is all gone from me, and I do fear sometimes that I must make a hospital for the hopelessly insane, and chain me up there such times, so I wont injure you” – Emily Dickinson, defining “chill” in 1852

Her breast is fit for pearls,

But I was not a “Diver” –

Her brow is fit for thrones

But I have not a crest.

Her heart is fit for home

I – a Sparrow – build there

Sweet of twigs and twine

My perennial nest.

—Totally casual poem Emily wrote in a letter to Susan, 1859

In her late twenties, Emily famously began a long period of reclusion, but in truth she wasn’t completely alone, she was eschewing the company of humans for wild nights in with Carlo. Although Susan was the audience for much of her literary output, the only creature that she shared all her work with was her beloved Carlo, whose patient nature could withstand her darkest of spells.

“Of ‘shunning Men and Women’ … He and I don’t object to them, if they’ll exist their side” – Emily Dickinson on her and Carlo’s understandable view of other people

“You ask of my companions. Hills, sir, and the sundown, and a dog as large as myself that my father bought me. They are better than human beings, because they know but do not tell.”

The only photo of Emily Dickinson ever.

Emily broke out of her depression for a period of prolific creativity in the early 1860s, producing almost 700 hundred poems between 1862-1864. During this intensity, Carlo was a steadfast companion, providing some balance for the manic Emily.

“I talk of all these things with Carlo, and his eyes grow meaning, and his shaggy feet keep a slower pace.”

Worsening health problems put the brakes on her literary output, and worst of all, Carlo died in 1866. Emily never got over the loss of her “Shaggy Ally,” and couldn’t bring herself to replace him. Without her protector and barrier to the outside world, her reclusiveness increased. She continued to write, but she never matched the volume of correspondence and poetry as those years with Carlo, and eventually succumbed to a long illness in 1886. At least she had this thought to comfort her: “I believe that the first to come and greet me when I go to heaven will be this dear, faithful, old friend Carlo?”

Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West

The protagonists of one of history’s most compelling lesbian love affairs, Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West were both accomplished writers: Virginia, now famed for her experimental novels, while Vita’s work encompassed poetry, travel writing and journalism as well as novels. But most importantly, they both wrote about dogs.

Virginia’s family, although middle-class and financially comfortable, was highly chaotic and led to a childhood punctuated with loss (her mother died when Virginia was 13) and sexual abuse (by her stepbrother Gerald). Dogs would act both as a stabiliser during these manic years, and a bridge between Virginia and her sister Vanessa, who was generally considered the “dog person” among the siblings. Among their childhood dogs were Shag, an overly-docile terrier picked up on holiday in Cornwall who failed miserably at his rat-catching duties, and Jerry who would make continual bids for freedom from their home in London’s Hyde Park.

As a teenager, Virginia developed a crush on one of her mother’s friends, Violet Dickinson, and got her first practice at one of her least-reported, yet most frequently-used literary devices: expressing your repressed sexual attraction for girls by conflating them with dog feelings. Here she is, in a totes platonic letter, imagining herself as Violet’s Chow, Robert:

“I think with Joy of certain exquisite moments when Rupert and I lick your forehead with a red-tongue and a purple tongue; and twine your hairs round our noses.”

One of Virginia’s strongest canine attachments was with her sister’s sheepdog Gurth, who she would walk around Regent’s Park, giving her comfort during her times of breakdown, as well as providing inspiration for works to come. Although she would occasionally grow weary with Gurth’s constant vigilance of her, she grew such a high regard for him that often the best compliment she could give a human was to compare them to a sheepdog.

To supplement Gurth’s visits, Virginia and her brother Adrian got another dog of their own, a boxer named Hans, who she taught the very important trick of putting out matches she’d use to light cigarettes (a trick she’d teach all her future dogs too).

In August 1910, Virginia married Leonard Woolf, a friend of her brother Thoby’s. Virginia and Leonard did not have sex, but very quickly they did have dogs: the first called Max, then a Climber Spaniel called Tinker, who they adopted from a friend for a month, most of which Virginia spent carefully observing him. As noted by her nephew and biographer Quentin Bell “Her affection was odd and remote. She wanted to know what her dog was feeling but then she wanted to know what everyone was feeling, and perhaps dogs were no more inscrutable than most humans.” In 1919, the couple acquired a new terrier, Grizzle, who became an integral part of their life in Sussex, going on long rambles through the countryside with Virginia, while she and Leonard set up their print business, Hogarth Press.

This idyllic lifestyle was rocked by a gay interruption in the 1920s, when Virginia began her decade-long affair with Vita Sackville-West. Vita, born in 1892 to an aristocratic family in Kent, was confident and well-travelled; almost the polar opposite of Virginia, whose mental illnesses often kept her both socially and geographically confined. In her estate in Kent, Vita would corral her troops of Elkhounds, and kept multitudes of different breeds throughout her life.

The couple wrote copious letters to each other throughout their affair, and from the start they adopted Virginia’s practiced habit of canine allegory. This started simply enough, Virginia describing their first romantic encounter as so:

“The explosion which happened on the sofa in my room here when you behaved so disgracefully and acquitted me forever. Acquired me, that’s what you did, like buying a puppy in a shop and leading it away on a string.”

Then Virginia would liken herself to her own dog Grizzle, as a counterpoint to Vita’s thoroughbreds, and play the old “I really want to lick you – sorry – my dog really wants to lick you” card:

“Remember your dog Grizzle and your Virginia, waiting for you; both rather mangy; but what of that? These shabby mongrels are always the most loving, warmhearted creatures. Grizzle and Virginia will rush down to meet you—they will lick you all over”

Before long though, they advanced to creating an imaginary pooch named Potto who, at various times would stand in for either Virginia or Vita, or indeed as a metaphor for their whole relationship. Virginia, per ushe:

“Potto kisses you and says he could rub your back and cure it by licking it.”

Lamenting a separation, Vita writes:

“This letter is principally to say that Potto is not very happy; he mopes; and I am not sure he has not got the mange; so he will probably insist on being brought back to Mrs. Woof [sic].”

Whether this a way to obscure the nature of their relationship in a time when it was not at all acceptable, they were purposefully trying to find the most lesbian way to process their feelings, or they were just genuinely really shit at saying directly how they felt about each other is a mystery that remains to this day.

“Beauty shines on two dogs doing what two women must not do” – Virginia Woolf, wistfully, after watching her dog have sex in the park

Although Leonard and Virginia seemed happy enough with a sexless marriage, of course the affair stirred up trouble. In a total power move, Vita gifted the couple a black Cocker spaniel, named Pinka, from a litter birthed by her own purebred, Pippin. Both Leonard and Grizzle were jealous of the new arrival, but poor Grizzle was not to endure too much of it, and died in 1926. Virginia promoted Pinka to her chief canine companion, which of course meant lots of dubious mentions in her correspondence with Vita:

“Please Vita dead don’t forget your humble creatures – Pinker and Virginia. Here we are sitting by the gas fire alone. Every morning she jumps on my bed and kisses me, and I say that’s Vita.”

Virginia famously wrote Orlando as a pseudo-biography of Vita, and the dogs referenced in the book are based on Vita’s real-life canine companions. These include Pippin, as well as her chief elkhound Canute, and a Saluki called Zurcha that she acquired in Iraq and wasn’t super-impressed with:

“without exception the dullest dog I ever owned … nothing would induce her to come out for a walk – perhaps because I omitted to provide a gazelle. In the end I followed the historical tradition and gave her to a Persian Prince, who subsequently lost her somewhere in Moscow.”

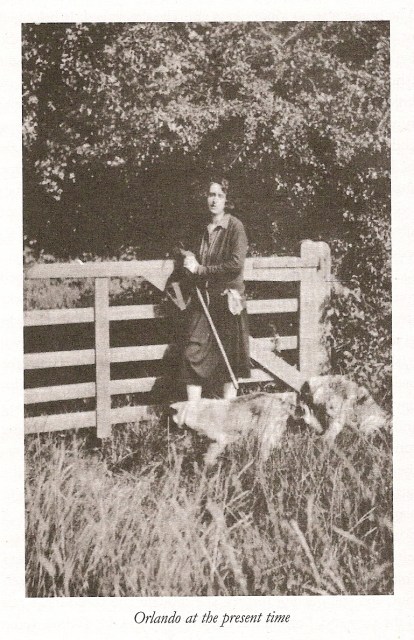

Vita and Virginia with dogs

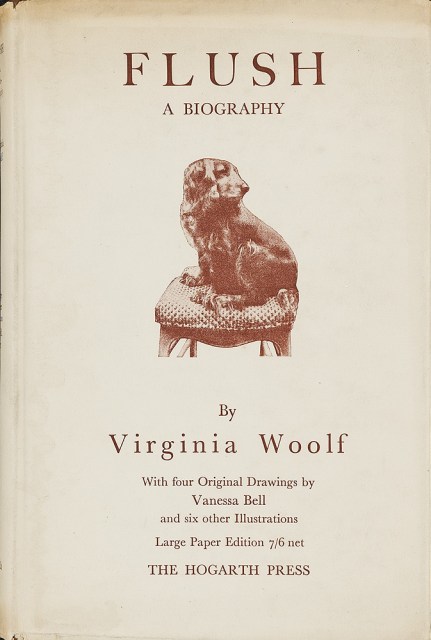

Virginia’s foremost foray into canine literature though, was Flush: A Biography. On the surface, a parody biography of the dognapped pet of Elizabeth and Robert Barrett-Browning, told from his own perspective, it also incorporates much from Virginia’s own life, including allusions to her childhood abuse and explorations of the human-canine bond, and draws from the many years spent walking her own dogs round the streets of London.

By the late 1920s, Virginia and Vita’s affair was on the rocks. Everyone processes breakups in their own way, and there’s a lot of good advice out there, but really is there any better method than comparing your failed relationship to the long and painful death of your imaginary dog?

“Potto is dead. For about a month (you have not been for a month and I date his decline from your last visit) I have watched him failing. First his coat lost lustre; then he refused biscuits; finally gravy. When I asked him what ailed him he sighed, but made no answer. The other day coming unexpectedly into the room, I found him wiping away a tear. He still maintained unbroken silence. Last night it was clear that the end was coming. I sat with him holding his paw in mine and felt the pulse grow feebler. At 7:45 he breathed deeply. I leant over him. I just caught and was able to distinguish the following words—“Tell Mrs. Nick that I love her….She has forgotten me. But I forgive her and…(here he could hardly speak) die…of…a…broken…heart!” He then expired….Oh my God—my Potto.”

Virginia and Vita remained on good terms after their romantic relationship ended, right up until Virginia’s suicide in 1941. Vita continued her writing, and become a celebrated gardener at her estate in Sissinghurst, where she created a small dog cemetery to commemorate several of her canine comrades, including Martha, Dan and her favourite Alsatian, Rollo. She drew together her love of dogs and travelling in her 1961 book Faces: Profiles of Dogs which combined photos of her favourite breeds with amateur history and her own anecdotes.

“Half the horrors of illness cease when one has a book or a dog or a cup of one’s own at hand.”

Mary Woolley and Jeanette Marks

Mary Woolley and Jeanette Marks were lifelong companions and educators who spent most of their lives fulfilling as many lesbian stereotypes as possible before the popularisation of plaid.

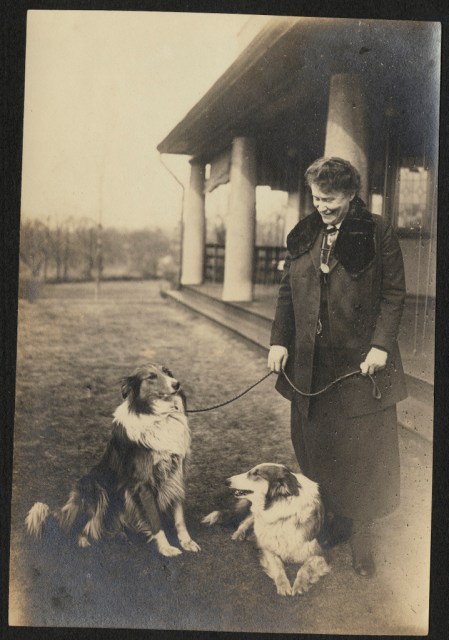

Mary and Jeanette with dog

Mary was born in Connecticut in 1863, and after great success as a student, began teaching at the all-female Wellesley College in 1895. That same year, the young Jeanette Marks began studying at Wellesley, beginning five years of simmering attraction between the student and professor, despite the 12-year age gap. In 1900, Mary got a job at another college and with the threat of separation, the pair’s slow burn burst into an incandescent reveal via a series of increasingly passionate letters.

“Jeannette – Does it seem possible that it is only a few short weeks since we have felt first we could say all that we feel, without restraint or constraint? Two such proud ladies, too, each one afraid that she felt more than the other and determined to keep her own self-respect!” – Mary Woolley, 1900, providing evidence that lesbians have struggled to work out if their gf really fancies them for 100+ years

Mary’s new position was as president at Mount Holyoke, another all-female college, where administrators had to rotate students’ rooming arrangements every couple of weeks to stop them getting too “attached” to one another.

I know a nice place for young girls to go, Mount Holyoke you know, Mount Holyoke you know,

Where life’s a gay whirl and things never are slow, Mount Holyoke, Mount Holyoke you know.

…

Here Freshmen fall madly in love twice a week, With a Senior you know, with a Senior you know

They load her with flowers but never dare speak At Holyoke, Mt. Holyoke you know.

– actual lyrics from Mount Holyoke song book 1901

Mary had a job on her hands to rehabilitate Holyoke from its past as the seminary from Emily Dickinson’s era, into a modern educational establishment. When Jeanette graduated, Mary was quick to use her powers of lesbian nepotism to install her as a teacher in Holyoke’s English department, and they began their life together, firstly in the college’s residential Brigham Hall, where Mary would climb three flights of stairs every evening to kiss Jeanette goodnight. In 1909, they moved in together to the newly-built President’s House, and soon filled it with Collies.

Mary Woolley

Woolley and Marks weren’t the only Collie-loving female educators in the state; the couple knew Katherine Lee Bates and Katherine from their time at Wellesley, who gifted Mary and Jeanette a Collie dubbed “Lord Wellesley” in recognition. He was soon joined by a pup called Ladybird Holyoke, and the couple usually had four or five Collies at any one time, including:

Old Mannie, Bird, Flag, Tyke, Turvey, Buddy, Chuckie Chuckles, Heron, Bummy, Blue Boy, Arrow and Tuttle

When Mary spent six months studying schools in China, she was welcomed back with a great fanfare to campus, with students lining the road singing specially-composed songs, and the Collies all decorated in bows. Mary also traveled to Geneva as the only American woman to attend a global disarmament conference, and wrote home to her dogs while she was there.

Jeanette Marks

While Mary’s career and reputation went from strength to strength, Jeanette struggled with indifference to her teaching role, stuttering success in her writing career, and the frequent feeling that her position at the college was purely because of her relationship with Mary. What’s more, while Jeanette had been a dog-lover her whole life, and was the driving force behind their ever-growing collection of Collies, and sometimes bred them, the dogs became known as Mary’s and become an integral part of her increasing public profile. Jeanette was said to be more than a little disgruntled that Mary had appropriated the dogs as her own.

“everyone who knows her knows her love of dogs and knows their devotion to her. For more than twenty-five years collies have been as truly members of the household as any human.” Mary Woolley, about Jeanette Marks

Despite these ups and downs, the couple remained together, and continued their work at Holyoke until Mary was prematurely ousted from her position as president in 1937, during a squabble about her successor. The couple retired to Jeanette’s family home, Fleyr-de-Lyr in Westport, New York, although both kept active with writing and public speaking. Mary’s health gradually began to fail, and she suffered a stroke in 1944. Still, Jeanette reminded her that they had “a pleasant and kind old home, happy doggies, good food and many faithful friends.” Jeanette cared for Mary until her death in 1947, and remained at Fleur-de-Lys, swimming daily with her beloved Collies, until she died in 1964, aged 88.

Ethel Smyth

Indomitable composer, author and general force of nature, Ethel Smyth was born in Sidcup, Kent in 1858. At the age of twelve, Ethel was introduced to classical music by a governess who had studied in Leipzig. Immediately Ethel was determined to become a composer and follow in her teacher’s footsteps to study at the Leipzig Conservatoire. Her father, a stern military man, objected to the notion, which only emboldened Ethel, who spent the next five years waging a varied campaign of arguments, silent treatment and general obstreperousness until she got her own way.

Travelling to Germany in 1877, Ethel fell under the wing of composer and music scholar Heinrich von Herzogenberg, and under the spell of his wife Lisl. For the next seven years, Ethel honed her musical skills while conducting an affair with Lisl who, at eleven years her senior, would be the first in a series of quasi-maternal objects of obsession. Things took a soapy turn in 1882, when Ethel travelled to Florence to meet Lisl’s sister Julia and her husband, the English-American philosopher Henry Brewster. Ethel developed a deep rapport with both husband and wife; Henry made advances that she rejected, but Ethel would go on to form a lifelong friendship with him. Julia, on the other hand, Ethel fell hard for, and thought nothing of sending lengthy letters to Lisl describing her newfound infatuation with her sister. Sadly, Lisl had not got to the compersion chapter of The Ethical Slut and her relationship with Ethel began to break down. Lisl broke all ties in 1885, sending Ethel into a state of creative and emotional turmoil she called “The Desert.”

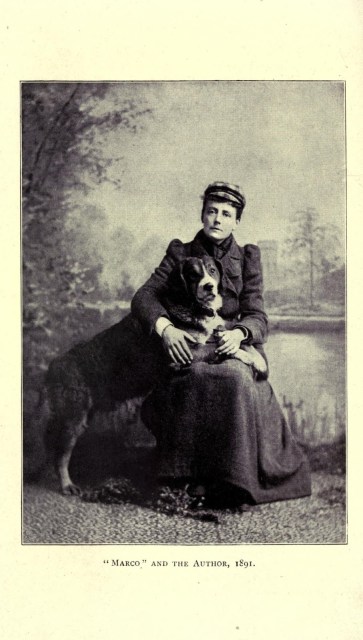

Ethel and Marco

Ethel found her way out of this bleak patch thanks to a gift from an old friend in Leipzig: “a huge sprawling yellow-and-white puppy of the long-haired kind generally seen dragging washerwomen’s carts. Half St. Bernard and the rest what you please, Marco was an entrancing animal…For twelve years that dog was the joy of my life, and latterly the terror of my friends.”

“A greater philosopher, a more perfect comrade for a busy woman, can have never existed” – Ethel on Marco

Marco stuck to Ethel’s side as she travelled around Europe, building her reputation as a composer of note. Marco also worked on his own reputation, interrupting a Brahms recital by knocking a table over (Brahms didn’t mind), and terrifying Tchaikovsky.

“Wherever I went Marco went, and wherever Marco went he made history.”

Ethel eventually consummated her relationship with Henry Brewster, which didn’t impress her hugely: “I remember arguing with him beside the Grandes Eaux as to whether any, any, any woman could ever have enjoyed such an experience.” Nevertheless, their relationship continued in the form of passionate letters, with infrequent meetings, while she pursued numerous entanglements with women. These included more keep-it-in-the-family love triangles with Mary Benson (an archbishop’s widow who shacked up with another archbishop’s widow, Lucy Tait) and her daughter Nellie, and with devoutly Catholic Pauline Trevelyan and her mother. In 1891, Ethel met Lady Mary Ponsonby, wife of Queen Victoria’s private secretary, and they enjoyed a lengthy relationship, no doubt helped by the fact that Mary didn’t mind Ethel’s constant flirting with other women.

Ethel and one of the Pans

After many years of travels round Europe and back to England, In 1899, Marco’s health deteriorated, and he was put down. On a friend’s recommendation, Ethel got a sheepdog puppy, that she named Pan, the first in a dynasty of Pan I – VI – all of whom she would chronicle in her book “Inordinate Affection: A Story for Dog Lovers.” Throughout the romantic inconsistencies of her life, the sheepdogs provided robust companionship, especially her favourite of the bunch, Pan IV, who she guiltily confessed she loved more than all the others put together.

“Mad keen on life in its every manifestation, yearly growing more beautiful, more adorable, and a more incredibly perfect companion, for seven and a half years we walked down the calendar, step by step” – Ethel describing Pan IV the way you wish your girlfriend described you

Despite increasingly failing hearing, Ethel consolidated her career a highly successful composer, with well-reviewed performances around Europe, and for more than a century was the only woman to have an opera staged at the New York Metropolitan. In 1910, Ethel took a break from music to fully devote herself to the women’s suffrage movement in England, specifically the militant suffragettes of the WSPU and their leader Emmeline Pankhurst, on whom she developed a giant and unrequited crush. The pair occupied neighbouring cells during their stint in Holloway Prison, where Ethel famously conducted a rousing version of her suffragette anthem The March of the Women out of her window, using a toothbrush.

Ethel and Virginia

In 1922, Ethel was made a Dame of the British Empire for her services to composition, but by the 1930s, her hearing loss forced her to all-but abandon music. Undaunted, she turned to writing, prolifically, producing nine volumes of autobiography as well as her dog chronicles. She was spurred on in her endeavours by the last of her great crushes, Virginia Woolf. Woolf was not particularly flattered at first: “An old woman of seventy-one has fallen in love with me. It is at once hideous and horrid and melancholy-sad. It is like being caught by a crab.” However, a woman of seventy-one has very few fucks to give, and Ethel mounted a successful campaign of badgering via letters, using killer lines such as “I had not meant to tell you. But I want affection. You may take advantage of this.” Although Virginia never returned close to the same level of affection, the pair wrote voluminous letters and met regularly until Virginia’s suicide.

Ethel’s health began to fail in the 1940s, and by 1944 she was worn down with illness and the premature death of Pan VI. Suffering from the pneumonia she would shortly succumb to, she told her nurse: “I think I shall die soon, and I intend to die standing up.” Although she did not manage that physically, she certainly stood up until the end with her indefatigable spirit.

Ethel and one of the Pans

Gertrude Stein and Alice B Toklas

Ultimate literary top Gertrude Stein and the woman whose autobiography she stole for herself, Alice B Toklas, met in 1907 in Paris.

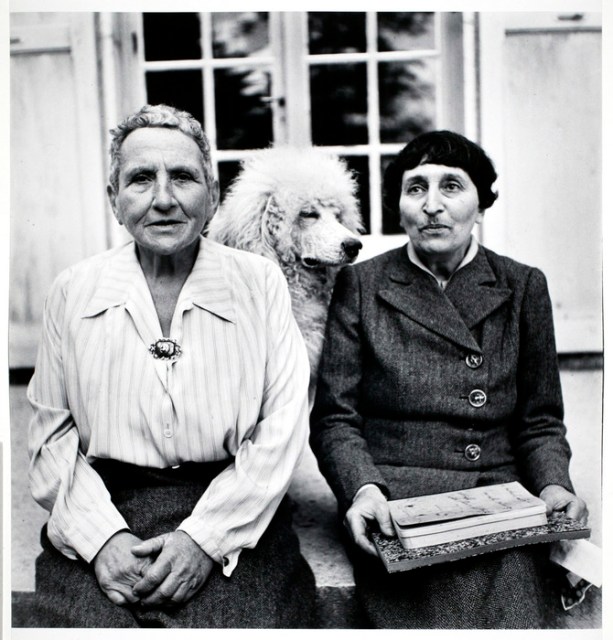

Gertrude Stein with dogs

Gertrude had relocated there in 1903, after a brief and bored stint as a medical student, to start an art salon with her brother with an inheritance. Alice was ostensibly taking a long-planned trip with a friend to Paris, and met Gertrude on the day she arrived. They fell in love immediately, but shockingly took almost three years to move in together. Thus began several decades at their salon, with Gertrude writing, while Alice cooked, and the pair hosted the artistic and literary luminaries of the day, including Picasso, Matisse and Hemingway.

Gertrude and Alice got their first dog, a Majorcan hound called Polybe, while holidaying in Spain. He was reddish-brown with black stripes on the back, enjoyed eating flowers and resisting all their attempts to train him. Although no pictures exist of Polybe, he crops up a lot in Stein’s earlier works.

By the mid-1920s Gertrude and Alice were looking to advance their U-Hauling to the next level and sought out a summer home in eastern France. While they were waiting for the paperwork for their new home to go through, they spotted a blue-eyed white poodle puppy at a local dog show in Paris. Alice said she had wanted a white poodle for many years, after reading about one in Henry James’s The Princess Casamassima, which is quite a feat considering the book doesn’t actually feature one. Alice christened the puppy Basket, because she “said he should carry a basket of flowers in his mouth. He never did.”

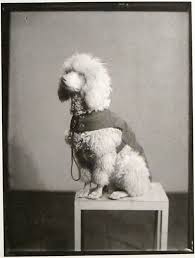

Basket by Man Ray

They moved to their new country home, and soon Basket grew into a bounding giant, and a star in his own right among their circle of friends. Dadaist photographer Man Ray took a series of portraits of Basket with and without Gertrude, Dutch artist Kristians Tonny painted Gertrude with Basket, and Picasso gifted Stein and Toklas Hommage a Basket as an offering after his own dog, an Airedale named Elf, had trampled over their flowers and got into a tiff with Basket.

An hommage to Basket

Basket was soon followed by a Mexican chihuahua gifted to them by artist Francis Picabia, on account of their admiration of his own chihuahua. They named him Byron owing to his overly-fond admiration for his own sister. His arrival engendered great jealousy in Basket, who ran away for attention. Byron died of typhus, but Picabia gamely provided another chihuahua named Pepe, who although physically identical to Byron, was of a much gentler nature and loved by all.

Gertrude and Alice with Basket II

Basket died in 1937, but the couple soon replaced him with another white standard poodle that they acquired in Bordeaux, who they imaginatively named Basket II. Unlike his predecessor, Basket II was fully pedigreed, and when war broke out and Stein and Toklas were living under German Occupation, this purebred status allowed Basket II extra rations, as apparently the Nazis obsession with master races was not limited to humans. Sadly, the winter cold got to Pepe, who became ill during the occupation, and died. Basket II continued on in great health, outliving Gertrude, who died in 1946. Like his predecessor, Basket II featured in several artworks, including a portrait by Marie Laurencin, which he is pictured next to in one of the most sublime images ever produced.

Basket looking at Basket

It is an astonishing literary omission that, having been propelled to fame by The Autobiography of Alice B Toklas, Stein never thought to dedicate autobiographies to Basket I or II, or any other of their dogs. However, she is the first on our list to have written a film about dogs! One of her few French-language pieces, Film: Deux Sœurs Qui Ne Sont Pas Sœurs, is a modernist take on Gertrude and Alice’s acquisition of the first Basket. It features versions of themselves in their own car, a picture of two poodles and one actual poodle, and sounds like quite a trip.

Other pieces of Stein’s dog-infused works include Doctor Faustus Light the Lights, and her short play Poem An Identity, which contains the oft-quoted “I am I because my little dog knows me even if the little dog is a big one.” Reading the piece with an anachronistic eye, one imagines it could be a poem created by a neural network trained on the fever dreams of visitors to a West Hollywood dog park (both human and canine).

“The person and the dog are there and the dog is there and the person is there and where oh where is their identity, is the identity there anywhere. I say two dogs but say a dog and a dog.”

After Gertrude died, Alice finally reclaimed her own life story and put out a memoir in the form of a cookbook, containing such classic recipes as Hashish Fudge. She continued to look after Basket II until his death in 1952.

As a fellow lesbian collie owner and dedicated Virginia Woolf fangirl, this article is everything to me, thank you

Thank you!

THIS IS BEAUTIFUL THANK YOU. I’m in the process of like…. seriously contemplating getting a dog. But my current place is not dog friendly, so I would have to move (which is a nightmare in Vancouver). BUT now that I’ve read this I’m re-committed to my future dog companion who I shall begin composing letters and poems to immediately.

Yes, this is the attitude I like to see! Please have your dog compositions ready to share with class for Part 3.

THIS IS EVERYTHING and I would die for any one of these doggos

I appreciate your sentiment, but also please stay alive.

gal’s best pal indeed!

#TeamDog #PawPatrol

Virginia! Adopt, don’t shop!

So fun and funny!!

MRS. WOOF

This was delightful, Sally!

This article is simply wonderful! The picture of GS with the big dog and the little dog and the vest and the big smile just warms my heart!

Sally this is stellar! Historical lesbians, dogs, humor, writers, more dogs and lesbians, drama – so many of my absolute favorite things. Not to mention meticulously well researched and delightfully written. My dog wasn’t pleased about waiting for his dinner while I read it, but he’ll get over it.

ok but Basket, Picabia, Pepe! i love everything about this

This is fabulous Sally! Also I don’t know if I’m inspired or disturbed by the imaginary dog metaphors between Vita and Virginia…but either way your recounting was hilarious. Glad I waited to read this until I had a suitable beverage I could spray-spit to maximum effect upon encountering particularly entertaining passages.

Please don’t send me the dry-cleaning bill after this spray-spit episode, thanks.

Had a bit of crush on Emily Dickinson as a child. Well meaning relatives gave the weird child books on her and Eleanor Roosevelt in hopes that I’d turn out a lady despite being weird perhaps, not knowing either of them to be queer and encouraging the weird.

So I get a mite giddy when she’s brought up in queer circles, but learning she had a giant sorta fluffy dog made me bounce up and down and making dolphin sounds.

Thank you Sally, made my day and possibly my month.

Not to incite further giddiness but maybe you will also see your other queer fave crop up in a future installment…

I would like to be considered for part 70, 100 years from now, when I’m a dead lesbian of history who was obsessed with her dog.

Ok, I’ve got you on the list that I’ll bequeath to my successor as the chronicler of dead lesbian dog obsessives. If you could also send pics of your fanciest doggy photoshoot, that will make the job so much easier. Or maybe they’ll be looking at dog holograms then?

This is great – I have so many favorite passages but this may be my favoritist.

This made me laugh, “Alice said she had wanted a white poodle for many years, after reading about one in Henry James’s The Princess Casamassima, which is quite a feat considering the book doesn’t actually feature one.”

Thank you for this important article!

oh, this is so delightful. emily dickinson was a dog lesbian! picturing her accompanied by a giant, slobbering newfie brings me almost unbridled joy.

Hey, some of the info about Virginia & Vita is incorrect. The ” Acquired me, that’s what you did, like buying a puppy in a shop and leading it away on a string” bit was actually written by Vita to Virginia. And Potto is a reference to “Bosman’s Potto,” which is a variety of lorisidae & was how Virginia often referred to the emotional/romantic/somewhat impishly affectionate side of herself.

“They named him Byron owing to his overly-fond admiration for his own sister.”

I snorted.