Last summer I regained touch with the cryptozoological community, a space I adored as a kid. Cryptozoology is the study of cryptids, entities that may or may not exist. This includes animals that aren’t scientifically recognized as real, like Bigfoot or Mothman as well as animals like the Tasmanian Tiger that are classified as extinct but that some believe are still living. While they may not technically be cryptids, creatures like werewolves, vampires, and ghosts are usually included in the interests of the average cryptid-lover. The cryptozoological community is a cultural space where UFO researchers, people who would eagerly buy a haunted house to talk to the ghosts, and people who believe in the possibility of everything from vampires to lake monsters mingle together. I came into the community as a member of that last category. I was a weird little kid who asked her parents for a Count Von Count doll rather than an Elmo doll because I loved vampires. I became obsessed with the Loch Ness Monster so early on in my development that the reason for the obsession is lost to my memory. What I do remember is flipping through the same four or five cryptid books in the library, a fear of the unknown mixing with excitement at the thought that there were so many strange, compelling things on offer in the world. Possessing the stubborn optimism of a child I reasoned that if I ever met a cryptid I would befriend it, because who said monsters were automatically bad? Maybe they just wanted someone to talk to. I know I did. In those days the cryptozoology community existed in pockets, with stories and theories about creatures passed on via books and T.V shows. As far as I knew, there was no other kid in my suburban town who was a member of the Loch Ness Monster Fan Club (a gift from a family friend who’d gone to Scotland) or who made charts comparing Bigfoot to the Yeti. Without a space to share them, I let my interest in cryptids go dormant, indulging it now and then with an episode of Animal X, a book of folklore or, with the help of my mom, a cherished pilgrimage to Loch Ness.

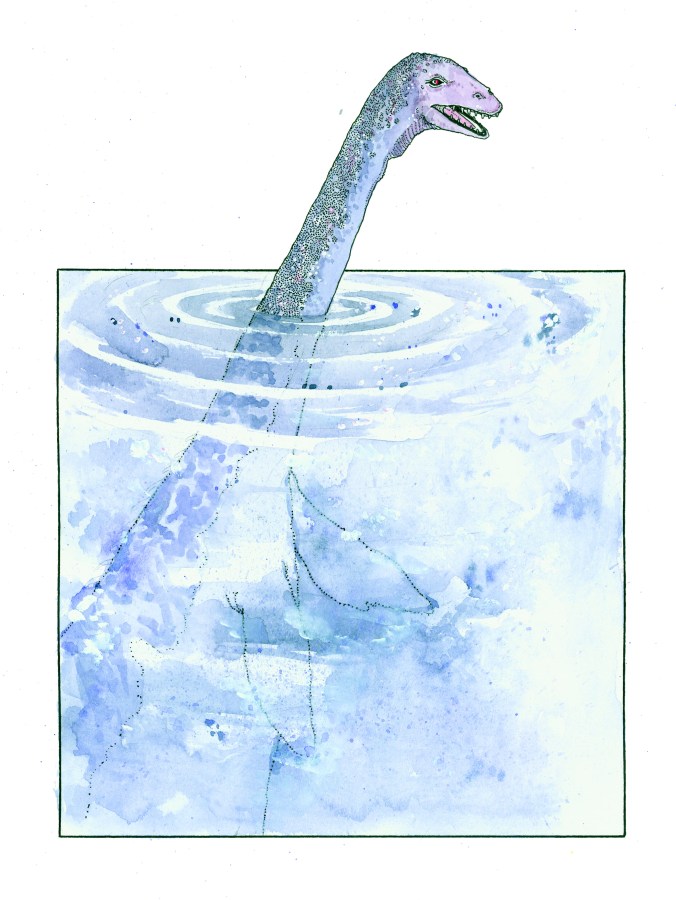

Loch Ness Monster, by Sophie Argetsinger

Fifteen years after little me sat studying monsters, adult me was a displaced Californian in Wisconsin, halfway through a draining graduate program. To lessen my stress, I needed to feed my creativity and explore my surroundings, and I realized Wisconsin had a lot of cryptids. I decided to visit locations associated with cryptids and write about them. I started a Tumblr called Midwestern Monster Hunt dedicated to my adventures and to sharing stories of the weird, macabre, and strange. I began following blogs devoted to lovingly curating blurry photos dotted with red circles, grainy images of discs in the sky, or puns about Mothman.

The more involved in cryptid and paranormal spaces I became, the more queer people seemed to pop up. There were people claiming The Flatwoods Monster is a lesbian, running blogs specifically for men who loved men (but also loved monsters), and designing pride flags featuring a different cryptid for each sexual orientation or gender identity. If this sounds suspiciously like the Gay Babadook meme, it’s because that joke and the queer presence in the cryptid community are close cousins. You can read a full run-down of where the meme came from and how it spread here, but basically The Babadook was miscategorized into the LGBT section on instead of the horror section on Netflix and some queer folks decided to embrace it as a new icon. The Babadook isn’t a cryptid, as it doesn’t inhabit the space between real and unreal and is instead explicitly fictitious. It doesn’t inhabit the “my existence is accepted but also denied” experience that draws many queer people to cryptids. However, the Gay Babadook is a very visible example of how easily queer culture and monster culture bleed into each other. It also emphasizes the role humor plays in that overlap. Lots of the content created by queer cryptid lovers is silly. Sometimes the humor is in imagining something potentially frightening, like Mothman, in a ridiculous situation (like continually crashing into streetlights like the giant moth he is). Other times, the humor is self-aware jokes that you should just date Bigfoot because you too are hairy and would like to live in the woods. But as I dug further into cryptid spaces, I found the overlap with queerness has deeper, more complex roots than a handful of jokes

In order to get to those roots, I interviewed my fellow bloggers and did my own digging to answer the question: Why are cryptid spaces so queer?

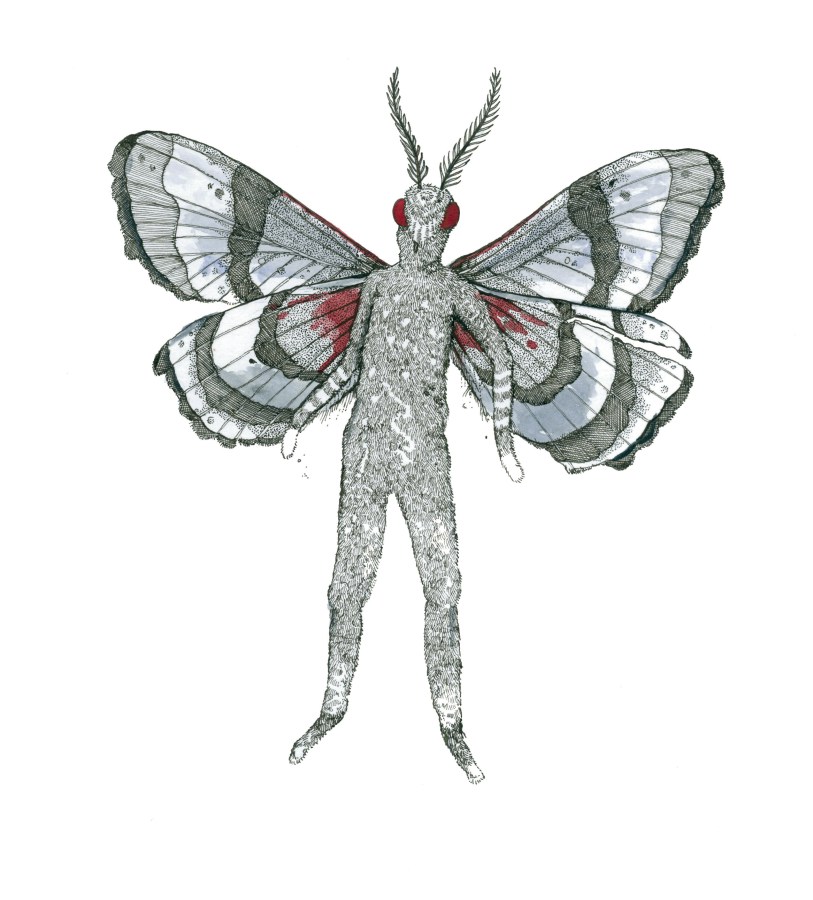

The Flatwoods Monster, by Sophie Argetsinger

For starters, they’re just weird. In weird spaces, non-normative orientations and identities feel less stigmatized. This can lead to a cycle where there start to be more and more queer and trans people in a space, further claiming it for those communities. And while there will be bigots in every cultural space, circles with “oddball” reputations tend to feel more accepting. As one blogger put it, in the event that their identity is challenged in cryptid spaces, they feel like they can better defend it because they’ve got a built in trump card: “you’re going to tell me you believe in Bigfoot but not gay people?” To them, and to others I spoke to, the idea of homophobia and transphobia existing in cryptid spaces was absurd because those spaces are explicitly built on the premise of accepting things that “normal” society won’t. Blogger Aislinn pointed out that the kind of people who gravitate towards cryptid spaces are, if anything, too eager to believe and accept things. While some cryptid lovers are skeptics (including myself) and others simply believe the creatures to be folklore, the majority firmly believe that cryptids are out there. They believe that our current understandings of the world are incomplete and that people should be open-minded to ideas that don’t fit tidily into their worldview. In other words, people in cryptid spaces are primed to be accepting of the unfamiliar, making them feel like safer spaces in which to express queerness. When they stepped into cryptid spaces, none of the inteviewees encountered the disbelief or rejection they’d received from family and community members. Some interviewees even cited that rejection as the reason they’d moved towards cryptid communities, as they believed finding the weirdos would bring them to a space where they were welcome. Online this is certainly the case, to the point that nearly every time I follow a cryptid blog it’s run by a queer person or a vocal ally. That pattern falters offline, partially because it’s not as easy to filter your interactions and because well-known cryptozoologists are generally white, cis, straight men. However, internet cryptid communities are acting as launching pad for young, queer cryptid lovers to create movies and webseries and attend conferences. If even a handful of those people maintain their involvement in offline cryptid spaces, chances are good that those spaces will become queerer as time goes on.

There’s also a hunger for representation running through this phenomenon. It’s not news that even in 2018, queer representation in media is not at the levels it should be. This presents a particularly interesting dynamic in the context of monster stories of which cryptids are a subset. Those stories generally hinge on some outside menace, some “other” threatening the status quo. But when you’re part of a marginalized group, be that queer folks, people of color, disabled folks, or any other identity that’s pushed into the shadows, the status quo mixed with the absence of anyone resembles you becomes menacing. The questions becomes: are those who are different being hidden, or are they hiding to protect themselves from harm? Cryptids embody both of those possibilities. They capture the feeling of being hidden because they are seen fleetingly or not at all, something many queer people can relate to. Cat, a Tumblr user, theorised that, “we (queer people) are hidden and so are these things so maybe we just subconsciously find solidarity in that.” Another user, Calvin, added, “enjoying the hidden things that no one talks about can be really fun for those who feel invisible in their own world.” I think we can extend that solidarity queer people feel for cryptids further by considering how both may hide out of self-preservation, because they are seen as a threat to be eradicated. Just as there are endless, soul-destroying debates about whether certain members of the queer community are a threat to various spaces, so too are there debates about whether cryptids are a menace to humans. For instance, blogger Savannah explained her fascination with Mothman as partially due to his being tied to a tragedy he may have had nothing to do with; the collapse of the Silver Bridge in West Virginia. In 1975, author Jack Keel claimed the collapse was in some way connected to the sightings of Mothman that occurred at approximately the same time, leading some theorists to blame the incident on the cryptid. The idea of being falsely framed as a threat strikes a chord for many queer people, and adds another reason why cryptids and queer people may be pushed into hiding. Nice, normal people want them to stay far away so that the community will remain safe. It’s not that those doing the pushing are against things and people that are different, oh goodness no. They just want the abominations to stay over there in the woods, so that they can’t do anything to the children.

Maybe familiarity with that baseless fear is why, when cryptids appear in stories, queer people embrace them. After all, the people who clutch their pearls and bite their knuckles in terror at monsters never really look like you do they? They look like the polite neighbors who clicks their tongue about “those people.” The dashing hero brings to mind the nice young men who hurl slurs at you like handfuls of rocks. If you’re not represented by the heroes and the civilians, that leaves two choices: accept that people like you don’t exist in that world, or lay claim to the creatures the status quo fears. Many queer people do, choosing to embrace the parts of themselves that are labeled monstrous. Queer coding of villains and monsters, and queer people’s response to that coding, has a long and complicated history that I won’t get into here. What I will say is there can be a lot of power in saying, “yes, I don’t fit within your narrow worldview, and I do not give two flying fucks about it.” If they won’t let you swim in their school, become a sea monster and devour them.

It doesn’t all boil down to power and menace. There’s a subversion in taking something unknown and feared and making it gentle and protective. In taking that which is labeled monstrous and naming it lovable. That’s exactly what a lot of cryptid-loving queers do. While cryptids in popular media are framed as dangerous (looking at you, two zillion Bigfoot hunting shows), the queer lens characterizes them as maternal figures, friends, or even potential partners. Over the last few months, especially in spaces like Tumblr, unrelated cryptids (as in, ones that belong to totally different countries) are being drawn in groups, a paranormal embodiment of the chosen family. Mothman is a favorite in these pictures, as is Bigfoot, the Fresno Nightcrawler, and The Flatwoods Monster (with the word monster often swapped out for “momster”). People also draw ads for Cryptid dating sites and joke about dating Bigfoot or Nessie. I asked why certain cryptids are depicted more than others, but many people said they just felt inexplicably drawn to a particular cryptid. Calvin did offer one reason, which is that they are non-binary and feel that a lot of their favorite cryptids could be non-binary too. I can follow that logic, especially in the case of the Flatwoods Monster and the Fresno Nightcrawler as they are presumed to be aliens and thus would not fit into earthly gender binaries. And if these creatures don’t have human notions and biases about gender (or sexuality, for that matter), maybe they’ll see queer people as kindred spirits and take them in. That might sound silly, and it might sound like a stretch, but the more I thought about it the less it surprised me that these friendly cryptid portrayals are created by queer people. Many of the creators are queer youth or young adults, people who want to build chosen families but whose age and resources make doing so difficult. When you’re in that position, you find creative ways to build a community, and maybe one of those ways is stitching together a cryptid family to escape into. Blogger FrankenLouie spoke about their experiences saying, “I’ve been dealing with a lot of parental abandonment and I like making characters and mythical creatures into sort of replacement parents. So giving them aspects of identities that I can relate to can make them seem safer.” Even if you’re an older cryptid-loving queer, these images can still offer you something you hunger for. When the structures and people that are supposed to protect you instead erase, oppress, or harass you, it’s comforting to imagine a world in which you can be welcomed into a space and enfolded in the warm embrace of Mothman or Bigfoot (not to mention Mothman looks soft as hell and probably feels like one of those fuzzy, Nordic throw blankets Google keeps trying to sell me).

Mothman illustrated by Sophie Argetsinger

Playing with the way cryptids are viewed introduces a new narrative, an alternative interpretation of stories both old and new. In that way, we can see it as an extension of something we’re called upon to do all the time: challenge the stories our culture tells itself, whether those are historical accounts that erase queer people or or movies that seldom bother to include us. An element I identified through my research was that interactions between queer people and cryptids act as wish fulfillment on a couple of levels. Cryptids thrive in isolation, in places juuuust out of reach of human hands. In the current social and political climate, a life of isolation in the New Jersey Pine Barrens or the woods of the Pacific Northwest sounds tempting to many of us. Throw in the fantasy of hanging out as part of a big cryptid chosen family and it’s easy to see why queer people become attached to the idea of cryptids. To some, they can basically represent a (slightly) weirder, spookier version of A-Camp.

There’s one more piece at play in this phenomenon. A sentiment I heard from multiple interviewees and have heard elsewhere in my life as a queer advocate, is that queer people have their experiences and existence denied all the time. Aislinn said that collecting evidence and defending the existence of cryptids, whether it’s in a serious or joking way, is doing for others what they wish was done for them. They pointed out that, “we can make the choice to validate the beast as something to fear, or inspire sympathy for it and promote its protection. I know that personally holds something empowering.” My friend Jess stated that cryptid culture provides an acknowledgement of the liminal space that it can feel like you inhabit when queer. For her, when she struggles to claim space in the world, when she wonders if she’s being seen for what and who she really is, the liminal spaces that cryptids inhabit (between known and unknown, real and fictional) start to feel familiar. In her mind, when you’re queer you feel a kinship with creatures that may never have their existence truly accepted and who remain outcast due to that lack of acceptance. Interviewee Jesse explained her interest in cryptids thusly: “maybe I’ve been drawn to them because they’re just as “weird” on the outside as I felt (feel?) on the inside. But I also remember wondering a lot about how cryptids might live. Like, day to day in their environment. I spent a lot of time thinking about them being in the woods alone. Wondering if they’re sad, if they’re lonely, if they’ve made friends with the animals like I do. I guess when you feel like an outcast (I usually had a hard time making friends) you become curious about other outcasts.” The outcast nature of cryptids generates curiosity, but also carries an element of fear. Cryptids tap into the fear of living a lonely, unconfirmed existence that many queer people feel. The worry that you’ll end up isolated somewhere, never fully recognized as valid.

For me, and for many of the people I spoke to, claiming cryptids as queer is a way to fight against that fear. When I step into cryptid spaces, I see people humanizing creatures in a way they wish others would humanize them while also connecting with other queer people. At the same time they’re creating art that de-isolates their favorite cryptids and gives them a big, hairy family, they’re pushing back against their own isolation by finding their people. I know that participating in the community makes me feel less alone. I’ve found other people in the wilderness and they have found me.The cryptids that fascinate us are at once entry point and anchor, introducing and connecting queer people to one another. In a world that’s often hostile, I’m grateful that monsters give me a way to find my community. The phenomenon makes me feel that in the event that the real monsters show up, I’ll have a people standing with me to face them.

This is a fantastic essay and now I want to learn so much more about cryptids and also cry a little bit for all the queer bbs making new parents for themselves ?

This was fucking amazing and YES to all of it. I’ve graduated from vampires to mothman but I’ve been into this stuff since I was a kid.

This was an amazing discovery, thanks ! I always downplayed my fascination with cryptids but looking at it this way is quite empowering. Gotta go, lots of monster sightings to catch up with…

Hi, yes, this made me cry, thank you.

If I am going to be monstrous, I’m going to be in good company with cryptids.

I love this essay, thank you for it. I tend not to be in spooky things, but I do feel a tenderness for cryptids. This also made me think of that tumblr post going around a while back about giant adult Teletubby cryptids. Here for it!

I wasn’t in to cryptids but after reading this I kinda want to be. This reminds me of one of my favorite Rilke quotes, “Perhaps all the dragons in our lives are princesses who are only waiting to see us act, just once, with beauty and courage. Perhaps everything that frightens us is, in its deepest essence, something helpless that wants our love.”

Wow that’s awesome

Loved this essay! Didn’t know anything about the cryptid community or its queerness before reading, and the deep dive into the psychology of it was really interesting and moving. Great piece, hope to hear more from this author.

I loved this, and my only regret was that it didn’t feature links to all of the queer cryptid culture discussed in the article, like the “pride flags featuring a different cryptid for each sexual orientation or gender identity”, which sound great.

Dang ! I forgot to mention the illustrations are totally awesome !

This was a enjoyable read and almost like a profile piece but from an insider’s view.

I was not aware-aware of the queerness of the cryptid community but I kinda expected or suspected the possibility for two reasons:

1) the queer coding of monsters in film/how much I know I ID’d with the “classic” monsters as a young teen

2) how queer the teratophile community I’ve been exposed to seems to skew (in case you didn’t know and are scared to google teratophile that means “monster-lover” and vampires but like Venom or those 6 ft furball of death werewolves with the corded muscles claws, teeth and more teeth)

“In weird spaces, non-normative orientations and identities feel less stigmatized.”

Yes.

Also can we be friends? You seem cool and I’d like to be friends.

I am Autistic and Asexual. My current interests in Marine Biology, Paleontology, and Mythology all evolved from my preteen obsession with Nessie, Champ, and other aquatic cryptids. To say this piece spoke to my soul would be a gross understatement.