The floor is chill on your feet. As you look down at your chipped toenails, you see how the tiled linoleum reflects the long, cold tubes of the fluorescents. The room is somehow both dingy and sterile, filled with alarming metal objects of indeterminate purpose and decorated by a faded poster of someone’s insides. It’s all bright and colorless but for a mint-blue table covering a gaudy Kleenex box, and a large, ugly model of a uterus molded from bright, 80s plastic. Oh, and the pamphlets, ads for medicines you’ll never need and promises of bright futures for the beautiful, thin white women who are smiling on their covers. The only color in the room is a whole wall of things that don’t relate to you. You hug your chest and shift your weight back and forth, making your papery gown crinkle. You wait, and as you lean against the exam table, the plasticky covering sticks.

The doctor, who you only meet once a year, if ever, is taking their sweet time getting there. You’re deeply uncomfortable before your pelvic exam even begins.

You don’t even want to think about that part.

The history of the speculum is, in a word, fraught. Though forms existed in ancient Greek and Rome, the familiar “duck-billed” speculum as we know it was invented by a man named J. Marion Sims around 1845. Sims, known by the ironic title as the “father of modern gynecology” invented the speculum in order to find a better surgical technique for repairing severe complications from obstructed childbirth. Over a period of nine years in Montgomery, Alabama, Sims ran his experiments on enslaved black women, obviously without their consent, and for some without any anesthesia. The use of anesthesia hadn’t yet been regularly accepted in surgical practice, but notwithstanding, the history of the speculum’s development lies in unethical human experimentation that planted the seeds of misogynoir in medical practice today. It’s a horrifying thought that the speculum he developed has undergone little to no meaningful change since.

This brutal start to the gynecological practice foreshadows the ongoing discomfort for people who need pelvic exams. It was considered morally objectionable for the all-male medical practitioners to study vaginal and uterine issues, even those related to childbirth. Sims himself had never practiced medicine on anything but dolls before he began his practice. In this light, the term “father of gynecology” is not just an ironic turn of phrase, but monstrous.

Sim’s Speculum (Wikimedia)

Enter Yona, a group of designers and engineers in San Francisco — founded by three women, Fran Wang, Rachel Hobart, and Hailey Stewart, Yona is dedicated to bettering pelvic exams. They’re certainly not the first to try and they have a ways to go, needing to overcome medical barriers and focus on better health for queer and trans people.

Nevertheless, the women who started Yona are optimistic about their efforts to redesign the speculum. The team works out of frog, a design agency notable for helping Apple design the revolutionary iMacs. The Yona project includes a redesign of the dreaded speculum, but it also looks at the pelvic examination as a whole, angling to find easy changes that can improve the experience in the examination room. Even beyond the speculum’s sordid history, the fact that its design hasn’t been meaningfully updated since the mid-1800s shows in our discomfort. Wang, Yona’s engineer, describes the object at hand:

“If you’ve never taken a look at the existing speculum, whether metal or plastic, they’re pretty scary-looking. If you play around with it, there’s a lot of jingling and rattling and clicking, and the whole thing looks like it’s not designed for a person’s body. It’s super utilitarian. There were a lot of directions we could take to improve this thing. [Unlike the original design], the first thing we were looking at is the patient comfort.”

The medical establishment is slow to change, requiring long clinical trial periods and even longer educational phases, historically prioritizing scientific efficacy over patient experience. Have you ever eavesdropped on your doctor’s notes when they discuss you? More often than not, it sounds something like “patient claims they feel such-and-such.” Patient-centered medical care can be rare, and like many fields, this focus becomes increasingly scarce and ineffectual when a patient isn’t the straight, white, cis male default.

Stewart described a conversation she found during her early research between the two hosts of a podcast called The Speculum. As one host described how well her pelvic exam went, the other host gasped as she realized that her own, terrible experience (with a rude, male gynecologist who didn’t use any lube) wasn’t the norm. She didn’t have to have put up with it. Stewart saw at that moment the power of pushing the topic and bringing vaginal health out of the shadows of taboo or impolite conversation, so as to empower others to demand better.

So the Yona team got to work. Alongside an impressive board of advisors, including a Lead Clinician from PlannedParenthood and the co-founder of MakeLoveNotPorn.tv., the Yona founders are working to change minds in the medical community.

Jose Colucci, formerly of IDEO and a director at the Design Institute for Health, describes the following five principles to make sure you have humans at the center of your design:

Ask questions and listen

Go and hear from the people at the heart of it. The Yona designers did this by listening to people who had gone through pelvic exams recount them afterward in their own homes. Stewart describes this process:

“It’s a topic that you don’t get to speak about unless you happen to have an exam at the same time as someone else. But every person we talked to expressed, ‘I could sit here and talk to you for hours and hours about this, thank you for giving me this opportunity.’ It was a humbling experience to be there, on their couches, in their homes.”

What’s missing is the reality that this may not be the case for every interviewee. While they spoke to a breadth of people — first-time examinees, women with HPV, pregnant women, survivors — I was dismayed to hear that they hadn’t spoken to a single openly queer, trans, or non-binary person.

Not yet, they corrected, and I felt some compassion for this — I’m a software designer and I understand that getting access to users can be difficult. Keeping up with every possible scenario is hard, as is working a big-impact passion project on your nights and weekends. But I’m first and foremost a bisexual woman of color and I know firsthand how feeling safe in the doctor’s office can be harder. Why is the onus on marginalized people to bring our voices to the table?

It will likely be a much more nuanced conversation when the Yona team expands their focus to queer and trans folks, many of whom need cervical health exams but may choose to forgo them rather than be misgendered, misunderstood, and mistreated, or have to experience healthcare that doesn’t acknowledge the often complex relationship queer and trans people have to their own bodies.

There’s some great secondary research out there as well: community resources! In the absence of care, people in the trans community are resilient and have created systems of whisper networks that allow trans people to care for themselves and get their needs met. They will circulate information on self-administration of sexual and gynecological health care, such as these zines from RAD Remedy, enabling people to take their health literally into their own hands in the absence of affirming care.

Observe

Questions and conversations get you started, but they only go so far. People will tell you what they think you want to hear, or what they believe is true, but that may not contain the full picture. For example, someone may describe the steps of attending the gyno like this:

“I go in, I take off my clothes, I wait, I brace for the exam and go through it, I clean myself, I leave.”

Six steps, at best. But when you observe them (always with their consent), you may notice that the last thing this person removes is their underwear, which they scramble off quickly underneath their medical frock and tuck into their pants so they’re not laying out in the open. You may notice that while they wait, they pull up a breathing app to calm themselves. You may notice that they paused for several moments before starting to remove their clothes, and made sure the door was fully closed. You may see them start when the doctor comes in, or wince when the speculum clicks wide. All these small moments can provide information that will ultimately help make the exam feel a lot easier.

Look to the extremes

Many times, in solving a problem for the most extreme possible case, you end up solving it for most cases. This is a foundational principle of inclusive design — solving the area that has the most friction makes it smoother for everyone. Take OXO, the food appliances company. Betsy Farber, one of the co-founders, regularly ‘hacked’ kitchen products to work better with her arthritic hands. Together with her husband Sam, they started developing more ergonomic kitchen tools, based on her experience. It was a huge hit, and OXO became a ubiquitous household brand. It turns out everyone likes more usable, well-formed tools.

Look to different fields for ideas

You can find good ideas in unusual comparisons. A medical team looked to NASCAR to redesign their operating room, giving them the idea of building quick-access kits, similar to those in pit stops, for common surgical emergencies. The Yona team visited sex shops to learn the ins and outs of pleasurable penetration (no pun intended). Wang describes how this led them to change the material of their design:

“Right now it’s usually a cold metal or plastic, where everything clicks. After going to Good Vibrations, we saw that most of the stuff out there that is meant for the vagina is silicone-based. We selected a body-safe surgical silicone to coat the outside of the speculum so that when it first touches you, it’s not cold. You don’t see it shining out of the corner of your eye when you walk into the exam room. We designed it to look less intimidating, to help manage anxiety.”

Metal speculum (Wikimedia, edited)

Prototype early and often

The Yona designers built early versions of their speculum with foam molds; this way they could bring doctors a potential shape and test it before they had to build something with expensive or hard-to-get medical materials. This back-and-forth process led to an early discovery that allows a gynecologist to use a speculum one-handed, as Wang describes:

“The current model has a 90° angle, super perpendicular and very square-looking. It was an aesthetic decision at the time, but we thought, why don’t we relax that handle angle a little bit? When we interviewed a provider, she was enthusiastic.

‘This is great because, with this slight change of angle, there’s more room for my hand — which means I don’t have to ask the patient to have that last “scooch” forward. So I don’t need the patient to be as close to the edge of the table as I would need to now.’ That was an amazing moment for us. We learned that we could affect the design so that the provider can get their hand in without actually touching the patient, which can feel very intrusive.”

Their quick prototyping also helped them decide on a three-leaf design which helps doctors get a better sightline without needing to open the speculum as wide, minimizing discomfort and pinching.

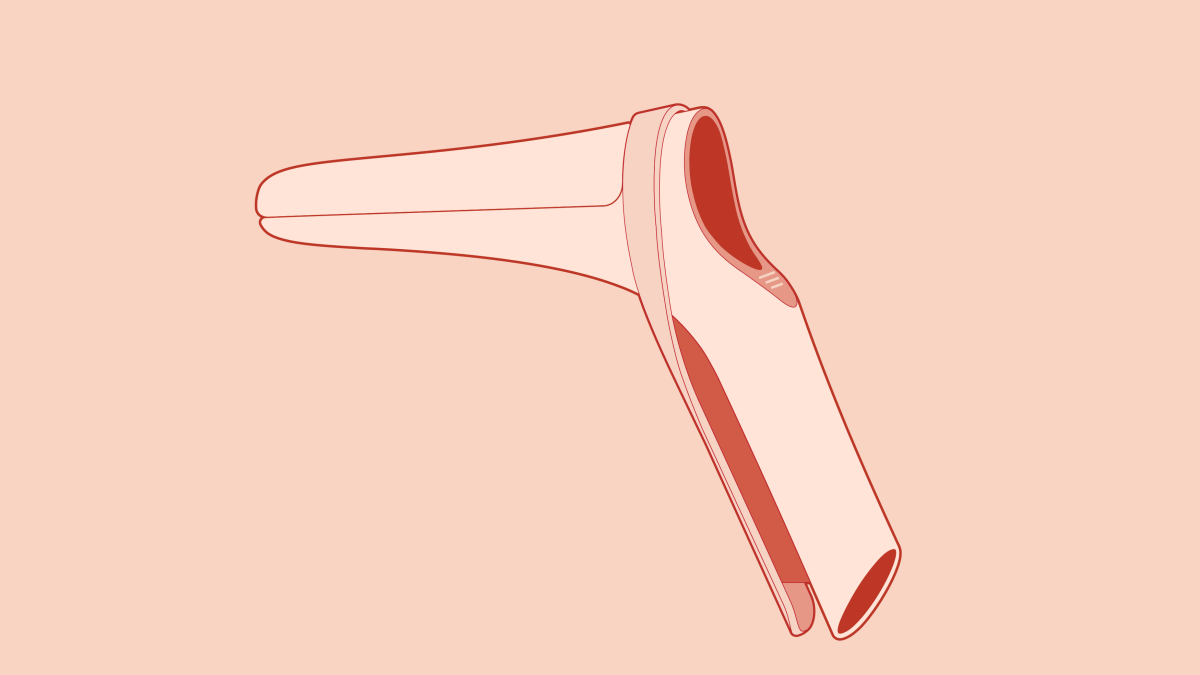

The speculum redesign (Yonacare.com)

Using these principles has helped the Yona team build an exciting alternative to the typical pelvic exam in impressively short time. Many of the people they’ve spoken to are hopeful it will come soon, but like any effort, it’s not without its gaps.

That third principle, looking to the extremes of a situation, is also where Yona have their most glaring omissions. Though their project centers around bodies in medicine, the design of their website assumes the users accessing it to be able-bodied, and most of their website is inaccessible to blind and low-vision users. While the cobalt-and-vermillion color scheme and soft peach text reflect an appealing trend in graphic design that has become industry-standard for cool millennials, at the end of the day even I struggle to read the site.

In their book Design for Real Life, Sara Wachter-Boettcher and Eric Meyer talk about the “designing for crisis” — finding the group of people who will use your design when they’re in their worst possible moment and designing for that scenario first. This idea came out of Meyer’s experience trying to find information in an emergency on how to enter the hospital — and discovering it wasn’t even on their website. His frustration and overwhelmedness at that moment underscored how important it is to find the situation in which people are most adversely affected by what is unavailable to them. The benefits of this are obvious: you’re avoiding an obvious point of failure and a lot of real, human pain. All the biggest points of friction and the riskiest, most dangerous decisions are considered and addressed before you get to anything else.

The tricky part is, how can you find the “crisis case” when the people who live it are being systematically erased, ignored, or driven away? The conversation must include and uplift the voices of people who are shut out from affirming, or even safe, healthcare: queer, trans, and non-binary people of color.

This is by no means a Yona problem; this is an industry problem. The response to the call for diversity and inclusion in business often leads to superficial change. Good marketing, gender-neutral branding, and lip service do not necessarily an inclusive product make. There’s a lost leap in consideration of what makes something inclusive beyond immediate social cachet. And the good intentions of the marketing team don’t always translate to structural support of underrepresented people in a product: Putting people of color on your hospital’s website doesn’t necessarily tell me if you’re working to mitigate the racial bias people of color receive at the doctor’s; calling for action after another school shooting on your #brand twitter doesn’t tell me if you’re taking money from the NRA’s lobbyists; changing your social media logo to a rainbow during Pride month doesn’t mean you’re also changing the policies that hurt your queer employees. While it’s a step, more often than not it’s too little too late — and queer people won’t trust it until we see real action.

So what does that take? A considered and constant centering of underrepresented people, working to overcome the structural inequities and the barriers to our entry in the spaces you (and your #brand) have long-inhabited.

It also takes coming to us in person and letting us speak for ourselves. Like the common refrain in the disability rights movement: nothing about us, without us.

Jamie, Yona‘s mascot (Yonacare.com)

I want to give credit to Yona‘s efforts. When you go to their website, you may notice there isn’t a “she” or “her” in sight. The Yona team made a conscious effort in their branding and identity to be gender-neutral. Hobart, their visual designer, describes why:

“Some male colleagues in the office, seeing our tagline Health for people with vaginas said, ‘Oh, you’re being provocative because you want to say vagina’. But we said, no, that’s a very carefully-considered decision. We don’t use any female pronouns on our website. We are taking a stance to push our company to be more inclusive, something we can all try to be better on and to improve. We didn’t do that with just the naming, but also with our character — the illustration style is aimed to be someone that anyone can relate to, we were initially considering skin tone and body type, but we also named this character an androgynous name when we call them: Jamie. It may not appear on the site, but among us, we always refer to Jamie as they/them.”

And they are making some headway. Hobart goes on to describe how these efforts have helped keep the team honest, teaching them to adjust their own language to be more gender-neutral, which can be a challenge in a “women’s wellness”- saturated space. They’ve also had an educational role with some of their board members and the design community, in particular, “women’s health” groups that may never have considered that not everyone who needs their services is a woman and that not everyone who is a woman needs their services.

As for Yona’s intention to start a conversation, they’ve succeeded, with some of frog’s star power behind them. They have been profiled in many big publications, including in Wired, Refinery29, The Atlantic, and The Washington Post’s feminist vertical The Lily and others, contributing to positive buzz for their project. Their Instagram feed is full of excited comments and thoughtful discussions over topics like whether the pelvic exam is even necessary (yes, they say, though it needs vast improvement).

Yona is keen to get those commenters to “begin the conversation” with their providers and build support for a new way of considering the pelvic exam. They provide downloads for enthusiasts to “bring into [their] community” with Instagram-friendly images and sassy hashtags.

And while I criticized marketing practices before, I’m not denigrating sassy hashtags! There’s been a sea change (though often centered around cis white women); the zeitgeist is on our side. People are speaking up on Twitter, in their offices, in marches. Hashtag campaigns ignite and connect people who are sharing their story, celebrating their communities and building activist networks. But again, the buck of inclusivity can’t stop there. At some point, the time for discourse ends, and the time to metabolize that conversation into concrete change begins.

Though I’ve criticized them for taking too long to talk to queer patients, the Yona Team is eager to make up for lost time. They want to hear from us — Autostraddle readers, specifically.

When I challenged them, Wang responded:

“Part of our process going forward is that we want to get more people involved, we want to get more voices heard. Up until now, we’ve mainly been constrained by time, working outside of work, and haven’t had the opportunity to talk to as many people as we’d like.

To answer your question more directly, yes, we want more people to talk to us, and we are listening.”

“You might get flooded,” I told her.

She answered: “We’d love that.”

This was a great article, so well researched and well-rounded. Thank you!

Thank you! ?

Autostraddle, you’re always so timely, but this went above and beyond. I read this at my gynecologist’s office waiting for my annual exam, and your intro was 100% accurate, except for the toenails part. I’m a socks on patient, but now I feel weird about it.

I’m also a socks on person, and my doctor always says “you can keep your socks on” before she leaves, so don’t feel weird about it!

I’m a socks person too! I figure that if I’m going to be that exposed, my feet need to be warm.

I also always wear a lucky pendant that I can grab if I need to.

Oh my gosh! I’m sorry for the accuracy. ? I used to live in Texas so I always had sandals on…but you’re right, socks are probably better.

Thank you for all the sock reassurance! After posting I googled it and found that (at least according to one source) 1 in 5 people take their socks off.

This was fascinating

Thank you

Thanks!

Great article. I didn’t realize this until now, but I’ve been waiting 27 years for someone to ask me how to improve pelvic exams. I just (bravely) emailed them.

This makes me so happy! Thank you for sharing. <3

Wow this is fascinating and kinda squicky. Seems like these researchers are asking some important questions!

<333

This was a wonderful article, and so well written! Thank you so much for talking about this important issue and letting us know that there may finally be a change in future. Personally, as a survivor I find exams to be very difficult and I would welcome change to the current scenario

I’m glad someone thought about including post-op trans women- our vaginas don’t have as much “give” or stretchiness compared to cis womens’, and as a result, every time I’ve had a speculum used on me, there’s *always* been some spotting/bleeding afterwards.