I spent most of middle school feeling like a monster. That word clicked everything into place — the alienation I felt from my body, my struggle to get femininity right, the distance between my friends’ physicalities and mine. I looked into that gap and decided I must be some other kind of person, or maybe not a person at all. Monstrosity gave my internalized ableism a name and the fuel it needed to survive for over twenty years.

And why not? Movies from Freaks (the granddaddy of them all) to Don’t Breathe (just this past summer) insinuate that disabled folks aren’t quite like the rest of you, that there’s something unsettling, alien, and maybe malignant in us. American Horror Story: Freak Show didn’t spring fully formed from Ryan Murphy’s head; it played off our very real history of questionable employment in carnival sideshows. But what if monsterhood could be a source of pride and power? What if disabled people turned monstrosity on its head and into our rallying cry?

That’s what Brianna Albers hopes to do with Monstering, the first ever magazine dedicated to disabled women and nonbinary people. “Monstering is, essentially, a safe haven for disabled people, because it stands in direct opposition to the current sociopolitical climate,” she says. “ It’s an act of resistance. By centering the narratives of disabled people, we are resisting erasure; by celebrating what makes us monstrous, we are resisting dehumanization.”

Read on for Monstering’s origin story, how they’re fighting back against Trump, and ways to submit your work. This is what young me was waiting for.

Where’d you get the idea for Monstering?

Back in March, one of my friends founded Sapphic Swan Zine, and I remember thinking, “I wish there was something like that for people like me.” Because there wasn’t, at the time. There are publications that revolve around disability; there are publications that are written by and for disabled people. And yet, there’s nothing out there that speaks directly to the experiences of disabled women and nonbinary people, and I really wanted to see something like that. I wanted a space to call my own.

In early 2015, I was an advisor for Winter Tangerine‘s queer workshop “We Sweat Honeysuckle,” and one of my good friends put together a syllabus on queerness and monstrosity that introduced me to the whole concept. Later that year, I created a zine on disability awareness, which put me more in tune with disability theory and the magazine medium. So Sapphic Swan Zine laid the foundation, then I started a tag on my blog for things that gave me monstering vibes, and it really just unspooled from there.

There’s nothing out there that speaks directly to the experiences of disabled women and nonbinary people, and I really wanted to see something like that. I wanted a space to call my own.

Disabled people have a long, complex history as monsters in freak shows and horror films. Where do you think that association comes from? How have you researched it in launching the magazine?

Humans are resistant to anything that isn’t “normal,” and I think monsters are truly the antithesis of normality. We think of monsters as hideous, grotesque beings, this violent sore of humanity — which helps to explain how disabled people came to be considered monstrous, and why. We’re abnormal. In many ways, we do not make sense. Our minds and/or bodies have been warped, twisted, until they no longer resemble that which is considered human.

Subverting expectation can be an incredible tool, especially when you wield it for good — things like love, justice, self-acceptance, celebration.

I’m obsessed with the notion of disabled people as monsters, because it offers such a unique — and, I think, empowering — take on infirmity. Monsters strike fear and terror in the hearts of their victims, which suggests an ability to shape realities. Subverting expectation can be an incredible tool, especially when you wield it for good — things like love, justice, self-acceptance, celebration. Resources like Jeffrey Jerome Cohen’s “Monster Culture (Seven Theses)” and Susan Stryker’s My Words to Victor Frankenstein have been instrumental in my personal formation of monstering.

How does monstering play out for disabled women and nonbinary people specifically?

Just look at today’s sociocultural climate. Look at what the election of Donald Trump says about people like us: we don’t matter, we’re not worth fighting for, we’re subhuman. Women and nonbinary people are already considered monsters, because we don’t fit the “mold” of the patriarchy; our disabilities only make things worse. Ultimately it comes down to oppression and the intersection of identities. As a woman, I experience sexism and misogyny, but as a white woman, I experience white privilege. My disability is just another layer of oppression/privilege.

People aren’t recognizing that Trump and the ideologies surrounding his campaign are literally life-threatening for disabled people. We’re going to die. There’s no getting around that, and yet people aren’t talking about it.

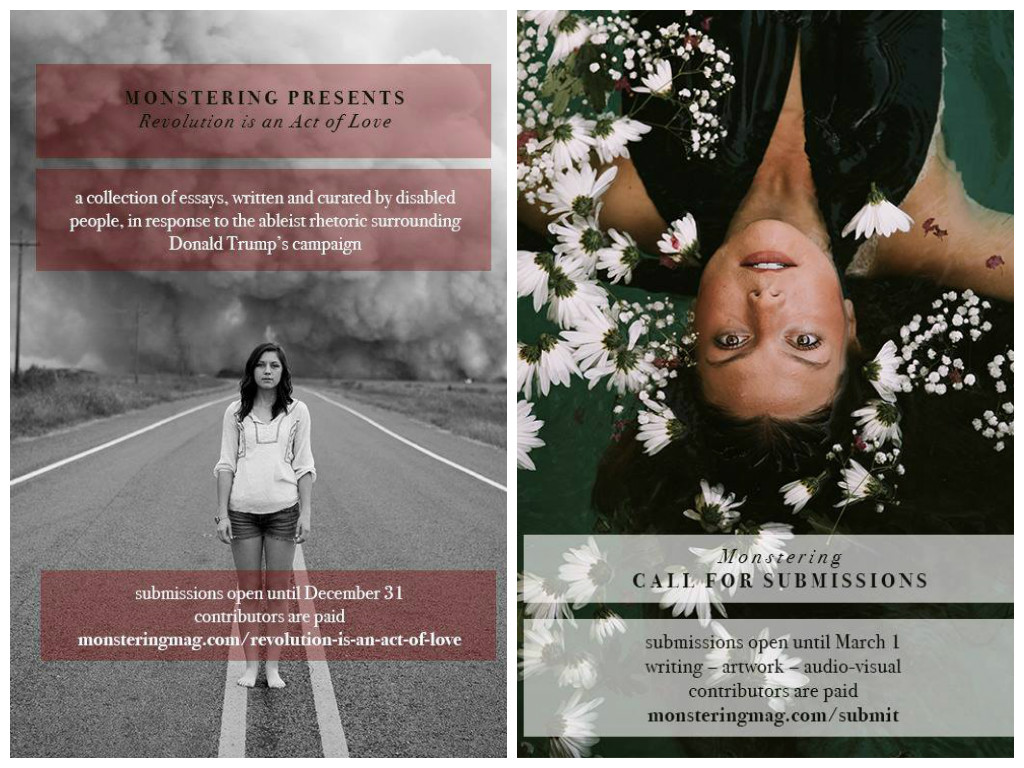

Speaking of Trump, you’ve announced a special anthology called Revolution is an Act of Love in direct response to his victory. Tell me more about that.

So many of us over at Monstering were shattered by the news of the election, and Revolution is an Act of Love is, I think, an outpouring of that. People aren’t recognizing that Trump and the ideologies surrounding his campaign are literally life-threatening for disabled people. We’re going to die. There’s no getting around that, and yet people aren’t talking about it. So Revolution Is an Act of Love is in response to that erasure — a way for disabled people to resist. Because oftentimes our disabilities prevent us from protesting, or calling our representatives, or any other acts of resistance that are currently being touted. Revolution Is an Act of Love is a way to ensure that our stories are chronicled, if not heard, even in the face of mass silence.

What is the power in monsterhood?

I get to take what the world uses to ostracize me — pain — and turn it into power.

Monstering — and the concept of monsterhood — has helped me forgive myself for what I perceived as monstrosity. For the things I can’t control, and the things I wouldn’t necessarily change if I could. This body is a vessel and nothing more. It can wield power, but it doesn’t have to ruin my life. In fact, it can actually make me stronger, if I just accept it for what it is. There is remarkable power in accepting ugliness, I think, because it’s a complete subversion of expectations. We get to turn the world on its head, which is something I don’t think I’ll ever get over. I also really love the fact that, as a monster, I get to take what the world uses to ostracize me — pain — and turn it into power.

I wanted to make a difference, and I wanted my disability to play a role in that, which is what Monstering — and the community surrounding it — has given me. I’m allowed to cherish what I am. I’m allowed to uplift and praise this thing called disability, while still allowing for things like anger. There is room for duality. For monsters to rise, singing. I absolutely love that about what we’ve created.

To add your voice to the monster chorus, submit to Revolution is an Act of Love by December 31, 2016 or the inaugural issue of Monstering by March 1, 2017. The submission guidelines are here. And hey, nondisabled folks: do your part by spreading this call far and wide. Because disabled people, especially those of us at the complicated intersections, deserve more space than ever to be our truest, weirdest selves — and Monstering belongs in the thick of that resistance.

I will submit to this!

Hooray! You should! I’m glad!

monster theory is an interesting collection of essays on this theme- i recommend!

Yaaaay Brianna! <3

This is brilliant!

THIS THIS THIS THIS THIS THIS THIS

Very interesting, thanks for reporting!

A bit strange to see conventionally pretty faces on the cover, but nevermind, I’ll wait to see the whole thing.

monster theory is a helpful and beautiful thing. only when will people understand that monsterhood is a is a grand, solemn, neverending ritual tinting your every action, not a political declaration. Literally the only case (in life or literature) of a pompous declaration that nevertheless manages a true transformed/liberated self-awareness is BoEM.

Do you take art submissions at all? I’m a much better artist than writer and did Autism and suicide awareness pieces you can find at these links.

Depression

http://einfarimarie.deviantart.com/art/Depression-How-it-changes-you-561959642

Autism

http://einfarimarie.deviantart.com/art/The-Stigmas-of-Autism-507606848

Hi Allicia! I’m the Editor-in-Chief of Monstering and I just wanted to say that we absolutely take art submissions. You can find our guidelines here: http://www.monsteringmag.com/submit. We’d love for you to submit! xo