I call Alda Talley my dyke fairy godmother. She is a self proclaimed “executive domestic goddess,” a small-town Southern lesbian who has spent her life fighting oppression through the art of hospitality. Alda and her partner Mary Capps frequently host younger queers at their home in Mississippi, where we laugh, eat and peruse their incredible feminist book collection.

Alda is the first person who told me about the New Orleans dyke bar scene. She came out in the 1970s, never having heard the word “lesbian,” and found herself at a bar called Charlene’s. “We would just drive by and watch from a distance,” she told me. “We did that several times before we got out of the car. We just stood a little way away on the sidewalk and practiced being lesbians at a bar.”

Charlene’s was one of over a dozen dyke bars in a scene that flourished in the 1970s and ’80s. Alda tended bar there in the late ’80s and welcomed in the baby dykes who came after her. “It did not always go peacefully,” she told me, “but it was never boring.”

Dyke bars during this period were spaces for identity formation, community building, political organizing, and celebration. All around the country these spaces are disappearing, or are already gone.

For the past two years I have been part of an effort to preserve the stories of New Orleans’ dyke bars and to recreate some of their magic through live performance, community events and digital media. Our collective, Last Call, has interviewed queer elders and hosted listening parties and live performances. On March 22 we released the first episode of our podcast series. Here are a few of the stories we’ve heard along the way.

Erica Langhoff, Moxie G. Rogue and Hannah Pepper-Cunningham in a Last Call performance

directed by Bonnie Gabel. Photo by Melisa Cardona.

Places to find love, or at least a lover

Before there was OK Cupid, one of the best places to pick up a lesbian lover was in a lesbian bar. When Liz Simon got out of a bad five-year relationship with a closeted woman, the first place her friends took her was Alice Brady’s bar on Rampart Street. “You deserve it!” they told her, “You’re getting your just desserts.”

Brady was one of the first lesbian bar owners in New Orleans, and her establishment moved between three different locations in the French Quarter over the years. Mary Capps remembers her bar as being attractive, a step up from a dive bar, with a great pool table. Brady was butch, but she always wore a skirt to avoid confrontation with law enforcement or homophobes. In the ’60s and early ’70s Brady was known for having strict rules. “No dancing, no touching, no kissing, no nothing,” Mary remembers. The rules were meant to keep the cops out in an era when raids of gay bars were still common, and two women dancing together could be arrested on charges of lewd behavior. “Everyone got evicted almost every night from the bar,” according to Mary, “You know, the rules!”

The rules didn’t stop Liz from taking a shining to an attractive young woman with a quick wit and Bette Davis eyes. Egged on by her friends, Liz approached her and struck up a conversation. “You know I’m new to the bar scene in New Orleans,” she said, “and I just saw you and noticed you and thought you were really cute and wanted to come over and talk to you.” They danced and danced, becoming increasingly flirtatious. “I think this is getting beyond the barroom floor,” the young woman said. Liz invited her home and they had a “jolly good night of it.”

Hannah Pepper Cunningham and Erica Langhoff. Photo by Melisa Cardona.

Liz remembers being on a high that night at Brady’s: “I felt free. It didn’t really matter to me whether I went home with anybody. It didn’t matter to me whether I talked to anybody. It was that I was going out as an out lesbian.”

Places to be free

Liz wasn’t the only person who felt free at the bars. The word “free” came up 40 times in our interviews. Hovering between private and public space, bars afforded lesbians the opportunity to flirt openly, dance and socialize with other women without as much fear of arrest or harassment as they experienced on the street. According to Mardi Youngblood, Halloween and Mardi Gras were the only times when it felt safe to be out, visibly, in public. The rest of the year, bars were a haven and an oasis.

Paula Kilbourne worked for the Jefferson Parish Sheriff’s Department in the 1980s and dreaded the possibility of being outed. “I worked Monday through Friday and wore that mask and those clothes that didn’t really fit me,” she remembers, “But on Friday nights and Saturday nights, I could be me. I could put on my blue jeans, put on my boots and I could go out and look as butch as I wanted to look. The bar saved me. It was my freedom.”

When Paula saw a drag queen hanging out at the bar at Charlene’s one night, it messed with her head. It was the first time in her life that Paula had ever seen a drag queen and she couldn’t help looking, although she tried not to stare. “How does it work?” she wondered, impressed. She imagined this fabulous drag queen being out all the time, whereas she would leave the bar and put on a skirt to go to work and pass for straight. She couldn’t sleep that night as she kept turning the image over in her head.

Donna Bechet-Kilbourne, one of our interviewees, performing in a benefit for Last Call.

Photo by Melisa Cardona.

Places to be powerful

Diana Panera remembers the 1970s as a “heady period of our power.” A feminist and anti-racist organizer, Diana took part in planning New Orleans’ first Take Back the Night march which drew thousands of people into the streets to protest violence against women. Diana was a member of WWAR (White Women Against Racism) and WAVAW (Women Against Violence Against Women), a group that trained women to be security marshals during the Take Back the Night march. When meetings let out, the conversations would continue over drinks at Charlene’s.

Diana identified as straight at the time, but she was happy to go to a lesbian bar. She always felt safe there. “Are you sure this is okay?” her friend Mary Capps would ask. Diana felt comfortable surrounded by women, and she was literally surrounded. Her friends would circle around to protect her from sapphic advances, but she would break away from the group. “They couldn’t surround me while I was dancing.” Soon enough Diana herself came out as a lesbian.

Bars play a central role in the history of gay liberation movements, most famously the Stonewall Inn in New York City. When people get together socially, they become aware of shared struggles and form group identity that can translate into powerful base building.

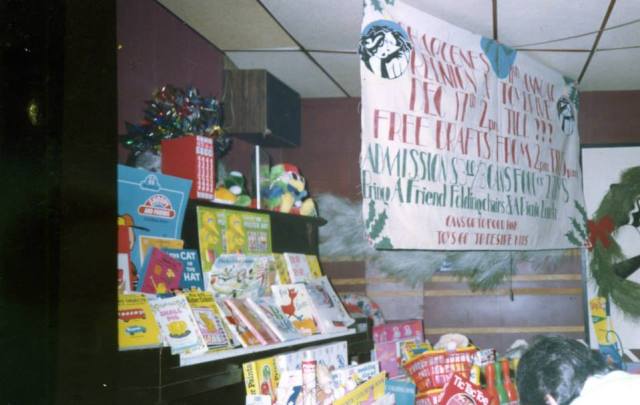

Charlene’s annual toy drive. Photo courtesy of Dianne Schneider.

Charlene Schneider, who owned the bar where Alda worked, capitalized on the collective identity of her customers to form political alliances. She would invite local candidates into the bar who were supportive of gay rights and she would hold toy drives around Christmas for constituents in the districts of politicians she favored. Sometimes she would take the mic at the bar and lecture the crowd, at length, about issues affecting the community.

Liz Simon remembers Charlene being radicalized by her experience at the March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights in 1979. “There was only about 100,000 of us, but they emptied all the federal buildings within two miles of the Washington monument so that nobody would be there to see us and so that we would have no coverage.” After the march Charlene started hosting meetings for LAGPAC, the Louisiana Lesbian and Gay Political Action Caucus, at her bar.

Imperfect places

Dyke bars could be a safe haven, but they were not immune to dynamics of racism, classism and transphobia. The same interpersonal and structural forms of oppression that shape heterosexual society still applied in the bars, sometimes blatantly and sometimes in more subtle ways. As Fikri points out, oppressive structures and behaviors have not been eradicated from queer spaces and need to be central in our understanding of “safety” and “freedom.”

Donna Bechet-Kilbourne remembers going to white bars with friends who were white: “Sometimes I would feel like I was the token black person there. And a lot of times white women would come up to me and ask me my opinion because I was representing the race for them.” Micro-aggressions like this stung, and made white spaces less welcoming for women of color. “We needed some place to go,” remembers Leslie Martinez. In the 1980s she opened a bar called Les Pierres with her partner Juanita Pierre. To their knowledge it was the first black lesbian owned bar in the city, and it was always packed.

Moxie G. Rogue and Hannah Pepper Cunningham. Photo by Melisa Cardona.

In her years as a bartender, Alda noticed more affluent lesbians, from suburban River Ridge, staying away from the bars. “The higher the class they were, the less likely they were to be at Charlene’s, or any of the bars at all.” These “River Ridge dykes,” who were more likely to live on their own in spacious homes and apartments, socialized at private house parties. “The lower the socioeconomic class of women, the more likely they were to be in the bars, because that’s where they could go and nurse one beer all night,” Alda told me.

Crystal Little, a lesbian trans woman, was openly rejected at Charlene’s in the ’90s. She was an active member of the LGBT Community Center and would go into the bar to drop off flyers for events. “I was known but I was also known as a trans woman,” she told me. “We were not welcome. You might have one drink and then the bartender might suggest that you go somewhere else. ‘Cuz we were not real women.” Crystal found a more welcoming environment at Rubyfruit Jungle, a lesbian club that didn’t “give a damn” about who came in the doors.

Back in the closet

Juanita and Leslie ran Les Pierres for almost a decade before they lost their lease on the building. They put their bar supplies in storage but lost everything in a burglary, making their prospects for re-opening impossible. Charlene’s closed in 1999, due to financial struggles, after 22 years of operation. Today there are plenty of gay men’s bars in New Orleans and a handful of pop-up parties that cater to queer and trans folks, but no lesbian bars.

All around the country lesbian bars are shutting their doors, or are already gone. Robin’s article for Autostraddle about the closing of the Lex in San Francisco attributes the disappearance of lesbian bars to gentrification, and even monogamy. Rising rents make local businesses unsustainable and when couples settle down they stop frequenting bars as much. Here in New Orleans interviewees have suggested that increasing acceptance of queerness has made bars less necessary as a safe haven. But as some forms of queerness become more mainstream, who gets left behind?

“It makes me very sad that I do not have a place to hang out,” Liz told me. “You know, it’s kind of like back in the closet again.” Many of the women we spoke with have active social lives; others are deeply lonely and isolated. One interviewee, a former bartender who recalled connecting women in need with free services from other customers, found herself homeless and living well below the poverty line at the time of our interview.

According to Juanita, the priorities of our community are out of whack. “I don’t want anybody to get it wrong and think that I am against gay people getting married,” she told me. “I’m not against it. It’s just not my forte. If you want me to get up and walk for free medical services, I’m there. Those are things that are needed. We have nothing for the gay women. And I don’t like it. Not because I’m gonna get old and gay. Because I’m already old and gay. But they got some of us that needs a little bit more than what we’re giving to one another.”

Last Call celebrates the stories of our elders while also acknowledging that they are still among us. The people who paved the way for us to be out and proud, whose lived experiences gave birth to the queer politics that shapes our identities, often live right around the corner. Many of them are active on social media and might just be a few clicks away from connecting with us. Others don’t use computers or don’t have internet access. Without physical spaces to find each other, how are we to learn from their triumphs and mistakes?

L: Dianne Schneider on a busy night at her sister Charlene’s bar. Photo courtesy of Dianne Schneider.

R: Rachel Lee presenting a birthday cake to Dianne Schneider during a Last Call benefit held in the space that used to be Charlene’s. It is no longer a lesbian bar. Photo by Melisa Cardona.

An invitation to listen

The Last Call podcast weaves together the stories of our elders with conversations and questions that we still grapple with today. We focus on a different topic each month: race, gender identity, police brutality, activism. The first episode is an aural collage of coming out stories from five people who frequented dyke bars in New Orleans with an original score by my co-producers Free Feral and Peter Bowling. Their words are funny, tender, and wise. Please join us in listening.

Last Call is grateful for the support of Alternate ROOTS, a network of artists dedicated to undoing oppression in the South. You can listen to our podcast here and follow the project on Facebook or on our website.

Thank you so much for this! I live in San Francisco and still feel a bit isolated. I romanticize the bar scenes depicted in Stone Butch Blues and this article. I agree that the struggle for marriage equality is not the struggle of all lesbians; there are other issues within our community worth worrying about and fighting for.

So proud of all y’all’s work and so honored to have been in the audience for the first “seed”! <3 <3

So sad to see that we’re losing our culture so fast =/

neat! gonna download this tonight!

This is so fucking rad, and I can’t wait to listen to the podcasts!

this honestly makes me so sad, you’d think that something like having our own lesbian bars would be more common now. the ONE pub in brighton that is ‘for’ queer women, isn’t even officially for us.

So sad. So widespread. This article is excellent, and I love the rich ethnographic content.

I used to go to Ruby Fruit Jungle and it was great. It’s so sad and confusing to see all of the lesbian bars disappearing, like what are we even doing?

Yes! Right after I moved to New Orleans I went to Rubyfruit Jungle during Dykeadence and it was the first time I’d ever been in an explicitly queer female space.

Oh man this sounds so good…I have never subscribed to a podcast so fast. It doesn’t play on the website though, or the RSS feed! You can play it through iTunes for some reason, so I’m still gonna listen, but I wish I could get it on my phone :(

Hi there! We just fixed the issue that was making the podcast not play on some browsers. Give it a try now at lastcallnola.podbean.com

Thanks for listening!

This was a great read – thanks. I’m going to listen to the podcasts too.

I used to have a drinking problem,,now that I don’t drink,,plus having mental health issues,, I’m shy and don’t like going to bars or clubs cus I don’t feel comfy but anxious etc. But if I could then I would love to go. In london, uk we have a single lesbian bar called She in soho. There are loads and loads of bars, clubs, nights for the guys / mixed but dominated by the guys. There are female nights in various places now and then. Not sure where yung gay women go in london. Maybe they go to str8 nights according to the style of music they like. We have black pride events a few times a year which r gud. And club nights maybe once a month specifically for eg. Indian/pakistani/bangladeshi of us, mostly men in attendance.. Yeh as lgbt ppl living under austerity economics there are 99 problems and marriage aint 1 lol. Just like with most str8 ppl here. Racist police shootings, deaths in police custody, institutional discrimination especially against muslims at the moment. In fact to be honest I can’t afford to go to a bar in london even for a coke.. With rent and transport etc so expensive I never actually go out. I last went out I think 2 years ago. But rich lgbt ppl can wine and dine every day of the week.