feature image via shutterstock

Last week I was in a bar with a few friends, all graduate students who funded their studies by teaching undergraduates, just like I’d been until recently. One friend — a very sweet and gentle man, of large, imposing stature — had been having trouble with a belligerent and disruptive student, and was asking us for advice about how to handle it in class. Someone — another man — advised laying down the law, illustrating to the rest of the class that this wasn’t acceptable. “Ask him in front of everybody why he thinks this is acceptable behavior in your class. Call him out where other people can hear you.” These were generally good ideas, I agreed. “But it’s important to do what’s natural to your teaching style,” I said. “If you’re not as authoritarian, if that’s not authentic to you, you don’t have to fake it. Maybe see if you can make a joke out of it when they misbehave, so other students are laughing with you instead of with them. Or if they’re trying to get a rise out of you, you can act really indifferent, apathetic.” I wouldn’t have considered any of the strategies my friend recommended very feasible for me back when I was still teaching; I didn’t have a lot of faith that my “laying down the law” as a 25-year-old woman would have carried much weight; it may even have backfired. In fact, during the whole discussion, I had a hard time really focusing on being helpful. Don’t ask me, I wanted to say. You’re a tall, burly man with a deep voice and degrees more prestigious than mine. You’re like Dorothy in teaching Oz — you can go home anytime you want, all you need to do is click those particular ruby slippers three times.

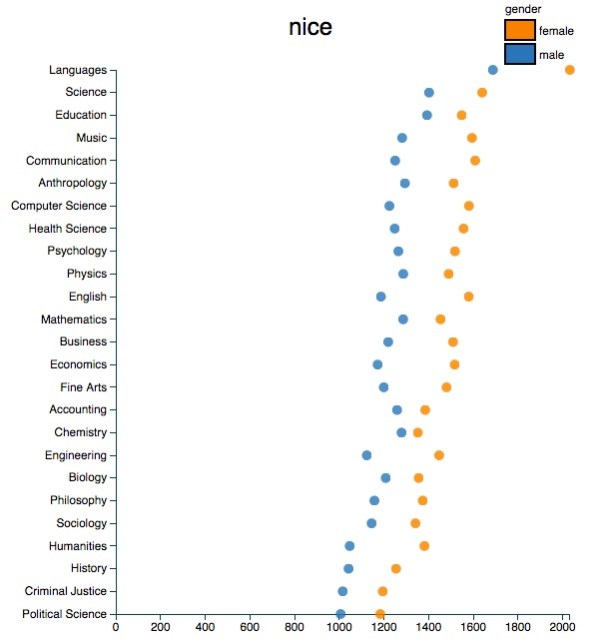

It’s not groundbreaking to note that the strategies required to succeed in teaching, a highly interpersonal job, are different for people of different genders. In the same way that we’re conditioned to read the same behavior by a politician, a rapper, or a bartender differently depending upon their gender, the social maneuvers a teacher need to make are calibrated differently by gender. This recent interactive chart of teacher ratings taken from Rate My Professor feedback is a fascinating, if limited, way to explore the ways that gendered expectations play out in the classroom. It really works best as a tool for exploration, as not much definitive can be extrapolated from the frequency of words alone. It tells us not so much how certain values are applied to different instructors, but whether they were considered at all. Even so, some obvious trends are telling: the mention of the word “nice” is skewed female, suggesting that we don’t tend to value niceness as highly when considering a man’s efficacy as an educator.

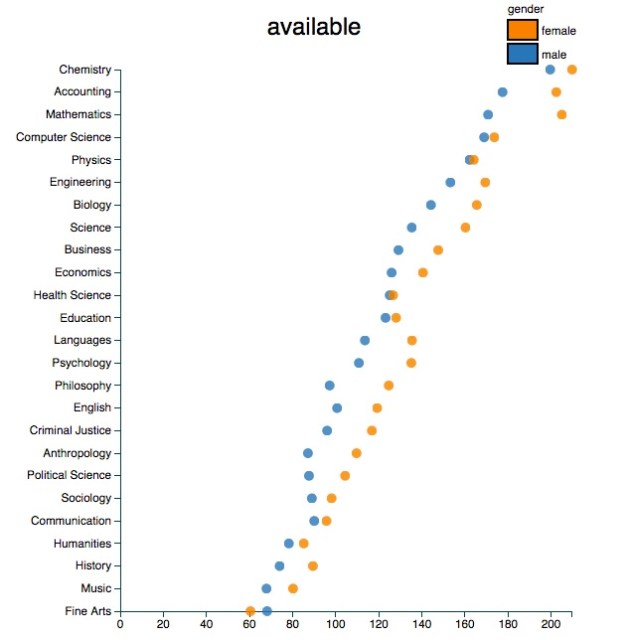

As a former instructor who was frequently frustrated by the many students who expected me to answer emails sent at 11 pm within the hour or were annoyed not to find me in my office at 9 am on days when I didn’t have office hours, I was interested to see a similar trend for the word “available” for most fields — perhaps echoing the cultural trend of women’s time not being considered as valuable as men’s, and the expectation that women be available to help or support others at all times. I wonder (without any definitive way to check) if my male colleagues were asked for meetings after 5 pm or on weekends by their students as often as I was. Although I didn’t have children or a family to care for, many women do, making this an especially outlandish demand that many students still feel entitled to make.

While Rate My Professor is an easily accessible source of information for sociological projects like this, it’s not a particularly important one in the real world, at least not compared to official course evaluations internal to a college or university. Whereas Rate My Professor is usually for students by students — figuring out that you should take Intro to Econ with Kant instead of Lacan, because Kant has a chili pepper and Lacan assigns too much homework — internal course evaluations are used in part to decide whether instructors should be granted more (funded) teaching positions in the future, and as assessment criteria if the instructor later looks for a teaching job at another institution (which many, if not most, in academia aim to do). Although that data is much less accessible to the public for analysis, it’s reasonable to expect that many of the same unrealistic assessments of female instructors are reproduced there, with more urgent real-world effects for the instructor.

Which is why this is a particularly frustrating example of the ways in which base sexism functions — because perceptions of women instructors’ personalities, as filtered through the gendered double standard both of educational institutions and individual college students, in their imperfect sleepy hungover youth, have very real consequences on the careers of female instructors and academics. What’s more, they have very real consequences on the educational experiences of students; when I’m worrying about how to teach without coming off as a bitch because I expect students to be quiet when I’m talking, I’m not thinking as much as I should be about whether my students are really learning.

My personal cross to bear as a female instructor — as someone who, in addition to being a woman, looked young enough that older professors sometimes mistook me for an undergraduate in the department office — was concern about being taken seriously. I agonized over my outfits, hair, and makeup; what formula of formal/feminine/hip/mature would communicate that I was professional and grown up, and so should be listened to? (It wasn’t uncommon for my male colleagues to teach in jeans and hoodies.) When a student disagreed with either the text or my own lecture, I often felt like I had to prioritize maintaining my own credibility when I would sometimes rather have had an honest (and educational) discussion about how yeah, these things are complicated and the academic answer isn’t always the right one. Other instructors in my grad program would sometimes use examples from their own personal lives to illustrate ideas in the classroom, but I never felt very comfortable doing so — I was too aware of the fact that many people think of women as being professionals OR having a personal life, and worried that if I acknowledged the latter, I wouldn’t be seen as the former. I rarely weighed in on how the issues we discussed in class — the sexism implied by Jamaica Kincaid’s Girl, the flawed rhetoric of advertising — had ever affected my own life, even when it could have been helpful, because I was worried that if I was perceived as having a personal bias about any issue, it would be a reason for my students to stop taking seriously anything I had to say about anything. It’s anecdotal, but I’ve never heard any of my male colleagues in academia worry about any of these things. I suspect this pattern holds true for other women, for many other women.

For these reasons and others, I also (almost) never came out during my time teaching. (I’m not alone; a recent poll revealed that only a third of LGBT teachers in the UK said they could be “out and safe” in schools. The issues they struggle with hold true globally, as this piece from the Atlantic illustrates.) I had at least one queer student virtually every semester I taught, whose identity I knew about either because they were out in class or because they mentioned it in writing assignments turned in to me. I assume there were more that I never knew about. I thought about them a lot, and what responsibility I might have to them, and how big a deal it had been to me when a beloved teacher told me she too was bisexual in the 11th grade. (Hey, Ms. M!) I did come out to one student, my very last semester as an instructor; she had brought up her own queerness in a one-on-one meeting, and sensing a need on her part to feel less alone, I had haltingly told her. I thought I would feel relieved and closer to her; instead, I just felt more anxious. What if she brought it up somehow in class?

Part of my reasoning for never coming out in most capacities was that in the state where I was teaching, it was still legal to fire someone because of their sexual orientation. While I knew several out teachers and my department never held a bigoted agenda, academic institutions will stoop pretty low if they decide they want to get rid of someone for political or economic reasons; it’s best not to give anyone anything to work with. (I did know one person who had a student object strenuously to the teaching of Brokeback Mountain, and experienced some pressure from the administration because of it.) But mostly it was because I was so anxious that if my students knew I was queer, it would be used as a reason why they didn’t need to take any of my urgent pleas to think critically and question the rhetoric of their communities to heart. That while my straight white male colleagues’ curriculum would be accepted as objective fact, mine would be written off by my students as a subjective screed, because the farther they saw my identity shift from that ‘neutral’ starting point, the less they would need to respect me as an educator and as a person, and the harder I would have to work to even get them to listen to me about commas. It’s likely part of why LGBT teachers are less likely to challenge homophobia in their classrooms — we know that we’re always risking making ourselves and our identities the focus of attention, and not the lesson, even at the risk of other students feeling less safe.

It’s important to note that there are increasing obstacles in the way of actually teaching the farther you get from the straight white male ideal, including many obstacles I never had to face — a friend who’s a queer woman of color has had students ask if she’s really qualified to teach English as a language, because being visibly brown is assumed to signify foreignness, is assumed to preclude expertise. It’s hard to imagine the student who asked that question really taking my friend’s lessons on anything to heart.

Trying to navigate sexism, heterosexism, racism and so much more in the classroom can often feel like it eclipses the job itself; perhaps even more insidious are the ways in which these concerns undermine the job at its foundation. While I was teaching Thought and Writing, I taught my students that if their understanding of logic and rhetoric was thorough enough, then their arguments and ideas would be taken seriously. At the same time, I was consciously editing and contorting myself because I felt that as a young female instructor, my own arguments and ideas would be dismissed, despite being the most educated person and (I hope?) the best writer and rhetorician in the room. During the personal essay unit, I taught them that relaying their personal experiences with vulnerability and honesty, describing them with as much concrete detail as possible, would ensure a connection with the reader that would make the scariness of personal revelation worthwhile. In those same in-class discussions and one-on-one meetings, I was taking care to conceal as much of my personal life and identity as possible, because I believed it would make it less likely that the same students would build a connection with what I was trying to teach them. Would my lessons on these topics have been more grounded in reality, and therefore more useful, if I had been able to acknowledge these contradictions in the classroom?

I don’t know for sure, but I do know that the position I was in as a female instructor didn’t help anyone, me or students. While teaching is often considered (and in many ways is) a “caring profession,” frequently associated with women, not many “feminine” traits really lend themselves to the field. It’s helpful to be understanding and compassionate, to have patience, be supportive and listen, but it’s also important to set boundaries, to challenge people in ways that often make them uncomfortable, to be direct and to welcome — even encourage — conflict to the extent that it can be productive to learn from. It’s not a coincidence that men as a group are often more successful than women in the “caring” professions. While women generally (correctly) understand that they need to default to gendered expectations in order to get anywhere at all in their profession — choose being a ‘team player’ over being assertive, prioritize the feelings of others over their own ideas — men feel (and are) free to be confident, ambitious, and confrontational. Women know that they’ll likely face pushback for doing these things, in any field; this may make them reluctant to do so when teaching, which is both totally rational and bad for students.

I got my MFA and left my program in May of 2014, leaving teaching behind with it. For now, at least, I’m glad to be done with it. I now work full-time with other queer women on this very website, providing feedback on their work in a way that’s not dissimilar from how I used to give feedback to students (although, granted, it’s now in a less bureaucratic and high-pressure environment). The difference is stark: when I’m not tasked with figuring out how to translate my thoughts out of my own lived experience and into the most “neutral” one I can imagine, I can focus on what the person I’m working with actually needs to hear. The difference in how much better am I at doing that job when I feel like I can be authentically myself, without so strenuously directing my own performance in the role of teacher, is remarkable. What would happen if teachers who weren’t straight white men were consistently able to feel that way in classrooms? Course evaluations aside, there’s no telling how much all of us might be able to learn.

This was a really great and thoughtful piece.

thank you laura you are a shining light

Such a though provoking piece. As a student, it feels so important to have professors who are openly queer because it creates a safe space and sense of understanding/support, and it’s crucial, especially in writing/lit classes.

Definitely. This is something I talk about with other queer students at both undergrad and grad levels. I’ve actually had a few students out themselves to me after class because of my openly queer identity, and it’s those moments that have been more meaningful to my job as a TA than quizzing students on Homo erectus skulls.

I never had an openly queer teacher or professor, but I imagine it would have made a huge impact in terms of comfort level and my willingness to be open. This comment really got me thinking about how different things would have been for me – especially, as you said, in writing/lit classes, which were the classes that most closely correspond with my career path today.

True story: I had a student drop a class after they threw a tantrum that I didn’t respond to their email on my birthday (which was a Saturday).

While I’ve been very fortunate in being comfortably out to students and to bring up personal anecdotes if relevant, I recognize that it’s more of a reflection of the general progressiveness within anthropology that allows me that luxury of being myself 100% (and the fact that 90% of us are women). That being said, a lot of what you’ve touched on here has been a factor in my acceptance that once I finish my PhD, I’m probably leaving the ivory tower. It’s been a bittersweet resignation.

I explicitly tell students,and repeat myself A LOT,that I do not respond to emails after hours or on weekends. I try to go the funny rout, by phrasing it like” i have a life where I’m not paid. Just like if you’re off duty at taco bell I’m not going to drive to your living room and ask for a chalupa.” I also find explaining what adjunct faculty mean, too.

Seriously? Who are these people?

leaving academia was bittersweet for me too, at least in a few ways, but one thing i definitely don’t miss are the emails sent twenty minutes before class starts saying “can you just look over my entire paper real quick and give me feedback so i can change anything i need to before we turn them in today.”

This was a wonderful article and I found it very interesting to read because education reform and expanding our cultural approaches to learning and teaching is something I’m really passionate about. I hope to, among other things, be a professor when I grow up, and I want to teach in a way that is authentic to me and meaningful to my students. Teaching goes both ways, after all, and I’d love to have the ability to be open and ambitious with my class so that I can learn from them as much as they learn from me. I’m trying to make steps towards being more assertive in the classroom so that one day I won’t have to feel like I should be neutralizing myself and my viewpoints. Currently I’m working with the English department at my high school to establish a new curriculum that will require at least one full-length work by a female author to be read each year for each grade level. (Despite the fact that around 89% of the kids at my school identify as women, I have only read one book by a female author in 3 years of English class, and not only is that an inherent example of sexism but it doesn’t fit our demographic.) I hope that whatever I end up doing as an adult, I can do it and stay true to myself and the things I am passionate about, because that’s when true learning happens.

that’s so rad that you’re working on your school with that project! i know so many grown adults with multiple education degrees that i wish were that committed, thoughtful and aware. i have no doubt that whatever you do as an adult, you’ll be a major asset to your field!

LOL Kant and Lacan. Love it. Also I would rather have neither of those men as my teachers…

ugh me neither, their syllabi would probably be impossible to understand

Rachel you have taught me so much over the years, I would love to be in your class…

this comment brings me so much joy! i would love that also. i teach writing workshops at camp! my policy on in-class texting is much more lenient there.

This was wonderful to read. I’m a queer phd student who is very out in life but not so much in my classroom, and you articulate so well the things that can make non-disclosure feel like the only possibility where teaching/maintaining professorial authority are concerned.

When I went through teacher training, I asked the powers that be whether coming out in class was a viable thing. Most of them just looked at me like it was a question they’d never confronted before (which is absurd given how many LGBT people there are in my program) and finally told me it was a personal choice that could go well or backfire completely. Which, ok, yes. But it feels insane to me that we talked and talked about every other aspect of teacherly existence while queerness never saw the light of day. I’m a couple years in to teaching now, and am still trying to figure out what sort of pedagogy might recognize and make use of the fact that I teach from a particular embodied position as much as students learn from them.

i’m so impressed that you asked directly about that! that’s great. and i know what you mean about LGBT stuff being covered terribly in training — in our training, we had a “privilege walk” exercise on the very first day, which basically asked us to out ourselves in front of a bunch of people we didn’t know at all yet as well as our program director. later in the same day of training the director just said broadly “and also sexual orientation can be a factor! is there anyone here who wants to speak to that?” and made pointed eye contact. i would have really appreciated someone with enough experience and training to facilitate a thoughtful conversation about how identity interacts with pedagogy. sigh.

This was a great piece and I forwarded it to a couple of my grad school friends. I’m working on a PhD in one of the hard sciences so not only am I a 24-year-old woman who is only a couple years removed from my students, I am frequently one of the only woman in the room when I’m teaching. There’s also no way to even subtly slip in a queer/feminist/whatever reference like you can in the humanities…

And sometimes I want to come out to them because I can’t think of any queer professors in our department, I can’t think of any where I did my undergrad, and I would have loved to have some sort of awareness of lgbt people in the sciences when I was an undergrad. And I know some of my students are queer, because they’re 18 and sometimes talk VERY LOUDLY about their personal lives in class.

I don’t come out publicly all at once or every quarte, but I’ve been known in cases like you just mention with students who talk loudly to mention in an aside that’s not private (step into the hall) or in front of the class, but like “hey I just overheard you mention blah blah and I want to let you know this about me because it’s important for us to be represented”. Because I’m bisexual and married to a man I find that I’m outing from bi invisibility , but then don’t out my non monogamy often.

i feel so lucky that my classrooms were usually fairly gender balanced — i can’t even imagine trying to teach a room full of primarily 18-22 year old men. holy mackerel. you are doing the lord’s work, kailey.

As someone who teaches middle and elementary school students and struggles with homophobia and general pubescent anger/hostility in the classroom, this was a very powerful piece.

YES! I work in a middle school and there is so much homophobia, biphobia, transphobia, racism, sexism…just everything. It’s so hard to correct kids compassionately, knowing that a big part of their development at this point is figuring out who they are, and that one of the ways they self-differentiate is by bashing others. It’s whack-a-mole, dude.

yes, it’s all so much to deal with! i remember feeling very overwhelmed and stressed out by the project of it — calling out and dealing with as much as i could, but always feeling anxious that the two kids whispering in the back of the room were saying something shitty that i should be addressing, or that if i heard someone laughing during a work period that it was some joke at the expense of another classmate that i should respond to. it’s Sisyphean, really.

I feeling very lucky that both my institutions of higher education are very gay friendly. I really don’t think I would developed a healthy sense of sexuality. If I hadn’t had out lesbian role models in undergrad.

i’m so happy for you that you had that! <3

This was a great piece. I’m an EFL teacher and I’m out to my adult classes (which hasn’t been an issue so far) but not explicitly out to my under-18 groups this year, although I have been ‘out’ with teenage groups in the past. They may have guessed anyway, since I dress in a gender-non-conforming way, but I’m yet to explicitly identify as queer in those classes.

I feel very conflicted about it. On the one hand, I really want to be a good queer role model for them, especially for those kids who will turn out to be queer themselves. On the other hand, I worry that open queerness could change the way they respond in class and could wreck the positive classroom dynamics I’ve been trying to foster. In any case, I call them out on homophobia, sexism, racism and so forth… but I always feel like I should be doing more.

“…but I always feel like I should be doing more.” God isn’t that so true of teaching in general! I really feel what you’re talking about here, feeling a level of accountability to students to be out or to be out in a certain way or to leverage identity in a way that provides something positive for them, but also I think it’s important to remember sometimes that that’s how we’re going to feel pretty much all the time as teachers anyway, like we could be doing more, because there’s always more that needs to be done. And if we know e’re going to feel that way no matter what, it kind of makes it a little bit easier to let yourself let go of it? I don’t know, maybe that’s just me!

I’m an EFL teacher too, and the dynamics are so tricky about being out because my students come from so many different cultural backgrounds–from Saudi Arabia to Brazil to Switzerland–and they are all at such different stages in knowledge/tolerance of LGBTQ issues. I know some students are totally queer friendly already, some really could use a push from me to learn more, and some would totally discredit me and do god knows what if they knew I was queer. So the result is I can’t be out to the class as a whole at all.

Also, being bi and having a male partner right now really makes this tricky for me, since I always feel like I’m hiding when I mention him in class and I know everyone assumes I’m straight.

I’m an EFL teacher, too. I teach in Southeast Asia which is generally very *Buddhist* about queer things in theory, though in practice things can get a little iffy…but I work for a foreign university that is based out of a Muslim country and staffed by conservative Muslims, so I have legitimate concerns about my job security if I were to come out. It’s a shame because I see so many faculty, staff and students blindly operating along SO MANY gender-based assumptions that I could just flick off with my pinky if given the security to do so.

Extremely interesting piece.

Please write (even) more for Autostraddle, please!

I am positive your feedback work is essential to the site’s writers, but your voice is SO special…

thank you blanche <3

Brilliant article, I’ve never taught vast swathes of mixed gender students so I think sexism is something I’ve only come across from their parents or from visiting male examiners or moderators. Outing fear though…

I teach in a tiny college where the staff outnumber the full time (16-20 y/o) students, all female, due to the number of specialised disciplines they need to learn and the nature of the industry (PA), we have many more part time students but I’m not involved in their learning. There is one male member of staff and other than that the staff is female and know myself and my partner well.

I never worry about being perceived as a bitch if I need to lay down the law, I don’t think any of us (staff) do because of the predominantly female environment it is. In terms of discipline, I’m harsh and I’m distanced. I try not to let them get a rise out of me but sometimes they go too far and get the quiet hard talk in front of their friends.

I am not specifically out to my students, although I used to hang out with one of my current student’s sisters so I’m sure she knows. I have never changed how I dress or how I cut my hair. I’m soft butch and I’m always honest about my clothing choices.

I teach like a games mistress from an Enid Blyton or Agatha Christie novel-British 1920s-1940s. I am not soft, I am fair, I am not mean, I am honest and if a student is upset, or let’s be honest here hormonal because with a massive bunch of women all in one place we have a week of hell once a month, I do my best but realistically I’m useless. I will support them with any educational worry they have, I’m the one called in to deal with inter student disputes because I’m seen as emotionless and rational, I am supportive of all their attempts to improve in any area of their work. I am stressed to the point of acid reflux, I am definitely terrified of being outed and my gayness being used as a weapon against me.

I think that comes from the fact that I was bullied unmercifully in school and due to section 28 my teachers were inclined to pretend I didn’t exist rather than deal with it. It was brutal. Truly. I fear that being such a small college anything hurled at me could spell the end.

I am so lucky that I don’t have to deal with sexism because almost everyone is female and the male member of staff is recognises the brilliance of his female contemporaries, he’s not gay, unlike many men in the industry. If I was a gay man I would have an infinitely easier time as evidenced by my GBF who worked with us for a while and was universally loved. There is one other lesbian on staff but she’s in an hour a week and has a baby so whilst she’s also not out at work her cover is more solid than mine…which is an awful way to view things.

I have never to my knowledge had a gay student, it’s a statistical improbability, other staff have been suspicious of some students sexualities. Particularly a girl who helped out in the office for a couple of years who I stayed in touch with after she left and am friends with and who knows I’m gay. They were suspicious because we were friendly. We had music in common and literature and art and the same sense of humour, which we discovered because we spent hours stuck in a tiny room together working on things together. Plus she was an oddball, she still is. She’s straight and I was horrified that any suggestion that she “liked” me was made just because we got on well and I’m gay. This is the sort of thing that makes me panic.

I’m not sure how I’m sane, or if I am. Does anyone else find little lies are way to easy after years of pronoun changing and “roommate” and “friend” because it’s less suspicious to say “I’m going in holiday with my friend” than “it’s none of your business” which is pretty rude…even in Britain!

I honestly think in a mixed sex environment working in fine art I would have an easier time, at the college where I am taking my MA lots of staff are gay and out, lesbians outnumber gay men, it’s like the promised land. I’m hoping to escape to that field once I pass my MA.

That sounds like such a stressful environment to try to live and work in, I’m so sorry you have to deal with it! I hope you can make it into the field you want to be in as soon as possible!

Thanks, I feel like I’ve been feeling it for a long time without articulating it, it came out here today. Apologies for the essay!

This 1000x over.

(I’m exceedingly thankful to my gay male colleague, who when I gave him a kinky (gay) calendar for christmas, asked where I got it from and I replied ‘at xxx’. We non-verbally acknowledged our shared sexuality and he’s never outed me or made an issue of it)

Hey, can we make this ‘See Jane Teach’ a regular feature, pretty please? I’m starting a PGCE (UK teaching qualification) in adult education this September so this was very interesting for me as a young lesbian woman who will often be teaching people older than me!

Been there during my Cert Ed training! Hadn’t graduated and had to have a teaching qual, it’s like 1000 less words on the essay for the final module than the PGCE I think…long while back now. Prepare yourself for Masses of reflective practice. Best of luck with it :)

Unfortunately this topic doesn’t really lend itself to a regular column at the moment, since I’m not actively teaching right now and I don’t think anyone else on the team is either, but definitely it will likely be really helpful for you to seek out other people that you have shared experiences with when you’re training for teaching and in the classroom. It makes it so much easier when you have other people to swap stories and advice with!

This speaks to me in SO many ways. I’m teaching English at a university in France as a random thing for a year, and have so keenly felt everything you have described! I do feel like I’m under scrutiny in very different ways from my male counterparts and it makes me rage-filled and anxious and tired and sad.

Also, this article made me think about what happened to Cheryl Abbate, the philosophy TA at Marquette University…

Yes, I live near Marquette now, and people are talking about Cheryl Abbate on talk radio and such all the time here! It stresses me out so much to think about.

Ali wrote about teaching in France as a woman at one point too, I don’t know if that might resonate with you!

Two gret pieces of advice given to me when I began teaching adults;

Don’t smile till Easter, &

“Watch out for the thirtysomethings”. “They think they know it all”.

Worked like a charm!

I had a friend and colleague who used that strategy — she worked on being a hardass for at least the first three or four weeks of the semester. I never felt super drawn to that strategy since my class was heavily discussion-based and I wanted people to feel comfortable so they would talk, but I’m glad it worked for you!

This is so on point, Rachel.

thank u <3

Very interesting!

This really spoke to my own experiences as a grad student instructor. As a butch woman, it’s been similarly frustrating having TA supervisors suggest I adopt a more “professional” mode of dress “because you look so young!” when the 24 year old men in my department get away with wearing jeans/hoodie combos that are far slouchier than my carefully put together business casual button-down situation. No matter what our gender presentation, it just seems like there are so many ways for us to “get it wrong” that our male colleagues don’t have to worry about.

Not to mention the senior male instructor who walked into MY classroom while my students were writing a quiz fifteen minutes before I was supposed to hand it over to him and, without looking at me, ordered them to put their pencils down so that he could use the room to set up his very important powerpoint.

oh my gosh that is so infuriating, i have no idea what i would have done. probably you handled that very gracefully, i probably would have just had an aneurysm.

and i know exactly what you mean about figuring out what to wear — by the end of my time teaching, i ended up being more relaxed, and was okay with wearing “nice” jeans where at first i would only wear slacks. it did feel like everything i did would be wrong somehow, and eventually it felt like if i was going to do it wrong, i could at least be comfortable.

Rachel, you are so good at this.

thank you so much heather <3

i really loved this aaaand i really love you rachel, that is all

I relate so hard to having to “perform professionalism” to get respect from colleagues, employees, and bosses. Thanks for this, Rachel! I’m glad you are working here now and can be 100% you every day. :) Or at least 99.9%

Thank you so much for writing this! I teach high school French (grades 9-12) in a state where gay rights are still a distant dream, but thankfully I am not the only LGBT-identified teacher at my school.

One of the biggest problems I have with high schoolers (especially boys) is that they will want questions that have nothing to do with the lesson answered in the middle of a lecture. Since they are still pretty young, I figure they just don’t realize how much this interruption can distract the teacher and the class. It gets to the point where certain students are limited to how many questions they can ask in class so they are forced to only ask very important and on-topic questions.

Being a hard-ass the first few weeks/months is key to gaining some kind of authority, especially when you are a woman AND young(er). It’s so hard to gain the respect of students, especially male students, when you are barely taller than they are and when they have just learned that some adults are taken aback by teenager sass.

I teach high school, and while I know I could make a difference by being out to my students, I have never seen an opportunity for it. I would like to see more pieces like this!

I really loved this article. I too recently got my M.A. and left academia for many of the same reasons. I’m glad I’m not alone and that you’ve shared your experience and insights.

I taught at a very conservative university in a state where it was legal to fire. I never truly considered being out (to undergrads) an option; I was full tuition/stipend (but teaching was required, regardless of any terms of your acceptance), but I could have lost my place in the program if anyone had kicked up enough dust. I received enough calls from parents (!) about other things to definitely send the signal that this would be a really bad idea.

I agree with what you say in the article. I felt the pressure to look ultra-professional to set myself apart from the students, whereas my fellow male students had a fresh-out-of-bed look. I let myself have fun in the classroom, but I did set strict outside-class boundaries about contacting me, etc. (one time a particularly thorn-in-the-side student called me late at night, at home, which I had made clear wasn’t an option; I told him he was calling during SVU, and I couldn’t talk then).

I was lucky to be teaching at a school where the classes were small (capped at 20 max in my department) and the students were mostly good (if not overly liberal). If somebody said something way in left field, I could generally just casually ask the class if they had a response to that rather than launching into lecture mode myself; the class would usually move toward addressing the issue (with me pushing a bit), and that kind of thing (in my experience) was better received from peers than from me. It was more of an issue in grading papers. It pretty much never failed that there would be one openly antagonistic male student per class that everyone was afraid to challenge, and those were the worst.

I know I’ve mentioned the White Noise “why women can’t be scientists” paper here before (written by the proponent of the argument that the slave in Candide “represents the healthy functioning of a free market system”). (Male) athletes were another challenge where I taught; the byzantine requirements for reporting academic progress and needs to coaches and academic supervisors for the team were a tremendous pain (and, in my opinion, mark of privilege– no other student was getting that kind of support– not even the people who were under the auspices of the academic disabilities offices got that degree of checking-in– and female athletes didn’t get it, either, for that matter).

I got my MA, took more courses, stayed on through comps, but left without writing my dissertation; between the teaching headaches, the academic infighting, the terrible job market, and personal issues, I was ready to get out of there and not look back.

(small bonus story: we weren’t allowed to grade in red ink because students frequently said it looked like teachers “bled” all over their papers, so I used blue Bics. Actual comment from eval: “She bled Smurf blood all over my paper.”)

well this was brilliant and just reiterated for me how lucky i am/we are to work with you, especially in a way that lets you be more of your whole fucking self. THANK YOU.

Brilliant writing Rachel.

I’m now in my 8th year of Education and have just started my second year in a secondary school re-engagement program for ‘at risk’ students. The last few months I’ve been struggling with my internalized homophobia and swinging between giving myself a hard time about not being out (and open) at work, and my firmly held belief that my sexuality is private. I can’t reconcile how I feel, so end up feeling conflicted most of the time.

Last year I directly confronted my students use of the word gay in a discriminatory, throw away manner by prominently displaying a ‘I just heard you say, that’s so gay!’ poster (inspired by the gsaforsafeschools.com) and directly calling students out each time. It didn’t stop the hurt I felt each slander, or the at times, arrogance of my students, but with continued effort, reduced the incident rate to about 30%.

But then I’d go into my staffroom where, due to demanding nature of our students, we’ve learnt some colourful language and constructed ‘joke’ phrases. The one I could not stomach was ‘That’s just because you’re a gay ass faggot’. Even after explaining to my colleague how much it hurt (even though not directed at me) and how inappropriate it was, she would tell me ‘I don’t really think/believe that’…I’d walk away with tears in my eyes, unable to explain or comprehend it all.

To my female student, who is out and dating at the moment, I want to tell her that it’s okay to take her jumper off in 38 degree (Celsius) heat, I know she’s cutting and I’m more concerned about her self care. That I know about her girlfriend’s struggles and the impact of that on their relationship. And that she is funny, smart, and oh so much braver than her teacher.

I keenly feel the responsibility of being a role model to my students, but feel so weighed down by all the ignorant bullshit that I’m left flailing.

As a former grad student T.A. and now an ESL teacher at a private school, I am feeling so much of this Rachel! Thanks for sharing.

Last semester I had the pleasure of being a TA for groups of straight, mostly white men. They were visibly shocked and confused when a woman walked in and introduced herself as the instructor for an engineering course. I made the choice to be out, but I didn’t announce it in the class- I let the information percolate through office hours and other means.

I had the luxury of being out also, I guess you could say, ironically, because I was teaching engineering. Math is math. No one could accuse me of teaching calculus in a “biased” manner because I’m a bisexual woman with a learning disability. In liberal arts teaching, where things are a bit more subjective, I bet many queer women face such claims.

It was after a student walked up to me and said “Hey, Laura, wanna hear a joke? What do you call two old lesbos doing it?…” that I realized the importance of being out. I was beaming with pride inside because the way I called him out was saying “You realize that I’m not straight, right?” and a couple of my other students came up and backed me up 100%.

In this area of Ohio, many people have never knowingly met an LGBT+ person, so just being out can mean the world. I’ve had gay men who are engineering students literally hug me in tears because they were happy to know that there was an engineering TA that they could talk to without worrying about homophobia.

I can’t speak to being out as a lesbian, because I’m bisexual. I know that immediately all of my students started hypersexualizing me, particularly because engineering is a field dominated by straight men. It’s difficult because we’re taught to believe that sexuality is private, but when I have students throwing around the phrase “that’s so gay!” and saying things about LGBT+ people and I know that there are a couple engineering students who have literally sat at home in tears because they think they’re the only one? Yeah. That could not stand.

I think this is the truest thing about teaching I’ve ever read. EXACTLY! EVERY WORD! Thank you so much for vocalizing all these struggles and tensions that are so difficult to bring to light sometimes.

I also started teaching during my masters (I did an MFA in Boston too!). I’m about halfway through a PhD now, love academia, but think about leaving teaching all the time. So much of this rings absolutely true for me and what I think about every time I’m in the classroom.