On Thursday, the Women’s Media Center released its third annual report on gender bias in major US media creation. The results, I’m sorry to say, confirm what many of us already know anecdotally: that women are underrepresented across the board.

Here’s the overview:

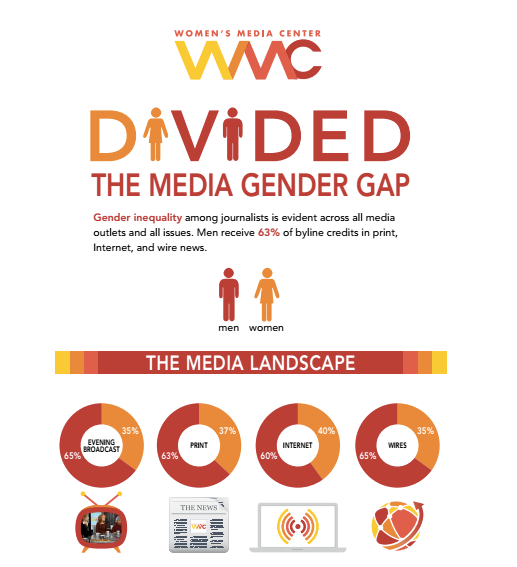

Men get about two-thirds of byline credits regardless of media type. Via Women’s Media Center.

And some lowlights:

- At the nation’s three most prestigious newspapers and four newspaper syndicates, male opinion page writers outnumbered women 4-to-1.

- Two women — 1.09 percent — were among the 183 sports talk radio hosts on Talkers magazine’s “Heavy Hundred” list. The Top Ten among Talker’s news talk show “Heavy Hundred” included no women.

- For production of the 250 top-grossing domestically made films of 2013, women accounted for 16 percent of all directors, executive producers, producers, writers, cinematographers and editors, slightly lower than the 2012 and 1998 figures.

- White men continue to dominate the ranks of Sunday morning news talk show guests, except on a single MSNBC show with a black female host.

In short: it’s bleak, and it has been for a long time. While there are a few women who have been very successful in spite of the odds, progress is uneven, and in many areas, there seems not to be any forward momentum at all. Women of color, spotlighted in the WMC report for the first time this year, are among those who have lost ground in recent years.

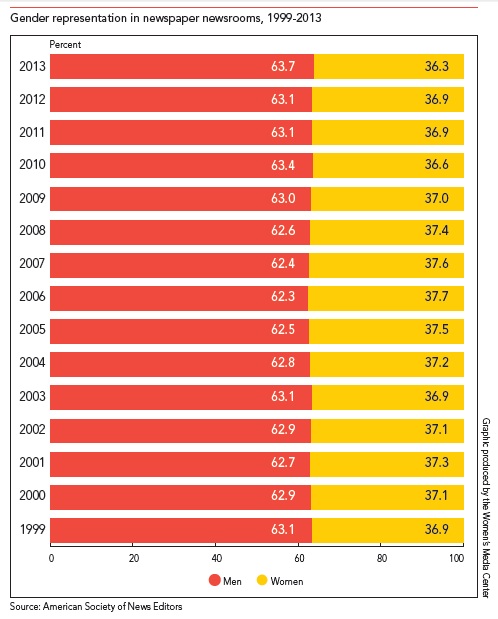

Not exactly a picture of progress. Via Women’s Media Center.

So why aren’t we seeing more movement towards gender parity?

One strong contributing factor is that the people holding the purse strings at many media organizations don’t want to take any risks that possibly could hurt their bottom lines. For advertising-supported media, content is created to appeal to certain audiences — most frequently, the same groups with disposable income that advertisers are trying to target (read: white cis men, ages 18-49).

When the cost of failure is very high, media creators often fall back on superstition, stereotypes, and past models of success to triangulate what constitutes a safe financial safe bet. For example, as our own Brittani Nichols reported in January, a prevalent (incorrect!) belief in Hollywood is that movies for and about men are also more likely to do well internationally than movies about women, despite evidence to the contrary. (Similarly, Brittani also reported that shows with more racially diverse casts perform better than those with less diverse casts, which hasn’t seemed to inspire any broad-level effort towards increased racial diversity on television.) With US filmmakers increasingly relying on foreign pre-sales to generate revenue, women’s roles in film have flat-lined. And why hire more women as producers, directors, writers, or other creative positions if most of the movies are going to be about men?

In many ways, it’s a self-perpetuating cycle. When people get the opportunity to hire and mentor others, they usually pick people who are like themselves, who eventually go on to hire and mentor more of the same. When one gender dominates the creative process, it inevitably comes out in the final product. And when media creators see gender-imbalanced content earning huge profits, they churn out similarly gender-imbalanced content in pursuit of similarly huge profits… leading other media creators to see gender-imbalanced content earning huge profits. Add racism, classism, and sexism to the mix, and we end up with a bunch of wealthy white dudes palling around with other wealthy white dudes, mostly telling stories about, you guessed it, wealthy white dudes.

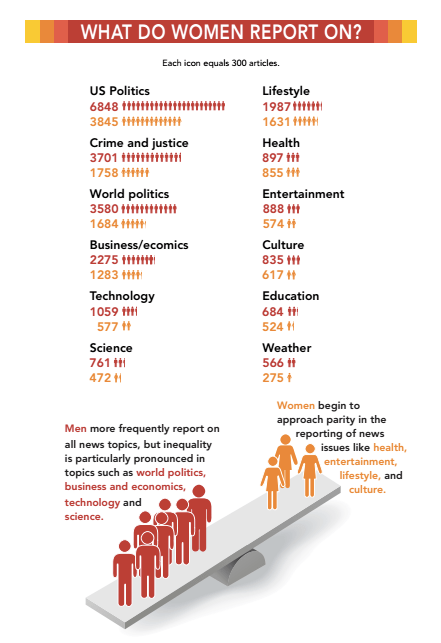

There’s some variation across categories, but men’s voices remain dominant no matter the subject. Via Women’s Media Center.

When media creation happens within this echo chamber, it’s unsurprising that the end results reflect a certain worldview. “We wonder why women are too often depicted as nags, flunkies or side salads. We wonder why women often get less to do, have less to say and so often feel the impulse to take off their shirts. We wonder why people of color aren’t often depicted with compelling emotional lives or as complicated characters,” Maureen Ryan at the Huffington Post astutely observed last week. “If the dictum of good writing is ‘write what you know,’ what do women and people of color know? … What stories aren’t we hearing from them?”

Media is a key force in filtering reality, shaping perceptions, and creating our culture. You’d think it should go without saying, but when certain men’s stories are blasted over and over worldwide as the only ones interesting and important enough to be told, we lose out.

In the post script of the WMC report, Geneva Overholser writes:

These findings confirm an ongoing truth that is not just disappointing, but unfortunate for all of us in so many ways. News media are at their best when they call upon the wisdom of all the people whom they serve, when they reflect everyone’s experience and bring in the hopes and dreams and fears of every sort of person. When media are overwhelmingly male (and still, alas, overwhelmingly white), they just aren’t anywhere near as good as they could be. The irony is that it would be good FOR the media if they were created by people who reflect this nation’s wonderfully diverse population.

Yes and yes. Weirdly, she goes on to say,

The decision-makers at these news organizations are at fault. … But we whose voices aren’t being heard are also at fault. We too often think our views are not valuable. It’s true that the absence of our voices in the media seems to send the signal that our views aren’t valued. But we know they are valuable. We need to try harder to make them heard.

Which… maybe not so much? There are so many systematic forces at work here; telling the underrepresented that we “need to try harder” is insulting, and I’m a little baffled why they chose to end this otherwise excellent report on this note.

Regardless, the practical tips provided in the WMC report are solid. For media creators, the report advises organizations to do things such as conduct personnel audits, avoid biased language and imagery, and monitor reader/viewer comments to make sure feedback doesn’t spread disinformation, racism and sexism. Media consumers are advised to speak up by writing letters to the editor, demanding more media ownership by women and people of color, and spending money in support of underrepresented voices.

For more, check out the report in its entirety.

woa, that was a little Sanberg-y there at the end, WMC. Y’all it has been OUR fault this whole time too!

I truly believe that the pressure Men face to succeed and provide has a lot to do with these numbers, in any profession. I’m constantly seeing charts about male dominated professions and perhaps if it was more acceptable for a Man to stay at home with his children while a Woman pushed to succeed in a professional environment, these numbers would change. I believe it has little to do with the patriarchy, and a lot more to do with society as a whole. We all have a place in this world, and we *all* contribute to these problems.

Amanda, I agree with you that the pressure on men to be providers is bad for society. Just wanted to point out, though — the idea that men all need to fit into this box of being breadwinners at the head of every household is, almost by definition, what the patriarchy is.

Story time:

About two months ago, there was a workshop held by my department on potential professions outside of academic. One of the panelists (white/cis/male) was a science journalist, and was talking about how he succeeded by writing a blog and emailing popular science websites about contributing.

During the Q&A, I asked the first question: “Do you think you can address the realities that 80% of the audience is women, and our experiences and successes online are not going to be reflected in your experience?”

He stuttered awkwardly and managed to splutter that he had heard of some awful stories about girls having their hardwork stolen and attributed to their male superiors. I corrected him that we’re talking about “women”, not “girls”, and he spluttered another apology, but ultimately couldn’t answer my question besides: “Women scientists have to support each other and promote their work.”

Yeah. Can you tell I’m still seething with the shortsightedness of his advice?

I just… Ugh. I can hear your frustration, and I echo it. The more I look at the impact of culture and the power structure, the more radical I get.