Welcome to the seventh installment of More Than Words, where I take queer words of all sorts and smash them apart and see what makes them tick. Every week I’ll be dissecting a different word, trying to figure out where it came from, how it has evolved, where it might be going, and what it all means. It’s like reading the dictionary through a prism. Feel free to send word suggestions to [email protected].

Header by Rory Midhani

Hey! It’s Christmas! Merry Christmas, Autostraddlers. In honor of the holiday, I propose we all partake in a tradition. Grab your ‘nog and gather around, and I’ll read to you all about Mary – blessed virgin, religious icon, and (did you know?) beleaguered hostess:

Bíide eríli wóoban with wemaneya wáa. Wóoban bi áwithid i ban bi zhath “Zheshu” áwithidedi wáa. Eril shi áwithid bith, i di bi eba bithodi, “Bíili, bre aril tháa ra áwithehóo, ébre aril míi le!” Id—bishibenal—menosháad womilá menedebe i noline menedebe i wothidá nedebe wáa. Eril medi, “Bóo aril meláad len áwithideth oyinan lu.” Bíide eril di with biyóodi, “Wulh hath áwitheláadewan! Methi ra bash i methi ra shal!”—i loláad bi ílhith. Izh di bi “Wil sha” zhonal: “Bóo mesháad nen i meláad.”

Always warms me right up. Since it’s the season for giving, here’s a translation:

Long ago, a woman gave birth in the wintertime. She had a baby boy, and she named him “Jesus.” The baby pleased her, and she said to her spouse, “If this baby doesn’t do well, I’ll be very surprised!” And then—suddenly—there arrived many shepherds, many angels, and several wise men. They said, “May we please see the baby?” “What a horrible time for a baby-viewing!” the woman said to herself. “They have no common sense and no manners!” — and she was disgusted. But aloud she said, “Please, come and see.”

A fairly familiar story, right? But an unfamiliar viewpoint, told in an unfamiliar language. A viewpoint enabled by, and possibly only reachable through, that language. Tongue-tied readers, meet Láadan, the constructed language designed to let us express ourselves so perfectly that we blow up the patriarchy. “More than words” is right.

Constructed languages, or conlangs, are languages invented by people or groups (as opposed to natural languages, which arise organically over long periods of time). People make conlangs for all different reasons. Authors dream them up to flesh out imaginary worlds (think Elvish, or Klingon) or to rhetorically constrict them – think Orwell’s Newspeak (doublethink it, even). Politically-minded idealists use them to try to solve global communication problems (Esperanto!); philosophically-minded idealists use them to try to solve personal communication problems, or to smooth the sometimes harrowing journey from brain to mouth (see Josh Foer’s recent knockout essay on Ithkuil, a conlang that was invented for one purpose and co-opted for another). Linguists of all levels build them to test theories. Some people do it in order to send more creative Christmas cards.

Láadan springs from all these impulses and aims high. It’s the runaway brainchild of Suzette Haden Elgin, a poet/novelist/songwriter/all-around wordsmith who started writing science fiction to pay for her linguistics Ph.D. and never stopped. In 1981, while reading about gendered language and mathematical philosophy, Elgin had a brainblast:

“I read . . . a reformulation of Goedel’s Theorem, in which Hofstadter proposed that for every record player there were records it could not play because they would lead to its indirect self-destruction. It struck me that if you squared this you would get a hypothesis that for every language there were perceptions it would not express because they would lead to its indirect self-destruction. Futhermore, if you cubed it, you would get a hypothesis that for every culture there were languages it could not use because they would lead to its indirect self-destruction. This made me wonder: what would happen to American culture if women did have and did use a language that expressed their perceptions? Would it self-destruct?”

If this idea wasn’t irresistible enough, there was the attendant theory (popularly known as “linguistic relativity” or “the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis“) that our conceptions and cognitive processes – our very worldviews and brains! – are shaped by the structure of the language we use (linguists have since corralled their sweeping enthusiasm about this, but it was very much in vogue at the time). Perhaps a constructed language, then, could help steer a culture. Plus, Elgin had already been speaking in public about the limitations of English for years, and she was often asked why, if there was such a big problem with the language, women hadn’t just made a new one, already. It was a good question. The gauntlet was thrown.

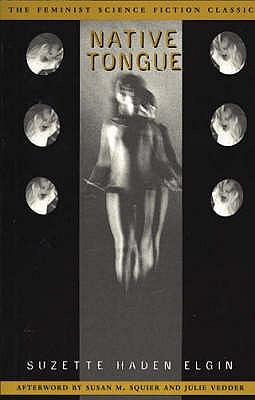

Elgin picked it up and wrote the Native Tongue trilogy (which – full disclosure – I have not yet read). The books are set in a future where Earth’s power depends on Earthlings’ ability to facilitate communication between alien races, and so linguists are high-class, powerful, and very talented. Meanwhile, in America, Congress has voted to retract women’s civil rights – the nineteenth amendment has been repealed, women can’t hold office or have intellectual lives and are considered dangerous when “not constrained by the careful and constant supervision of a responsible male citizen.” A small group of women begins building a revolution by slowly, word by word, creating a language, one that can “bring to life concepts men have never needed, have never dreamed of, and thus change the world.” Elgin decided that she wouldn’t be able to write a convincing and accurate book about the process of language construction unless she constructed one herself. On June 28th, 1982, she started constructing Láadan by hand, with the goal of creating a basic grammatical and syntactic structure and coming up with 1,000 words. By the fall, she’d far surpassed that goal, and had published that Christmas tale we read part of earlier, in Women and Language News. By 1984, the first Native Tongue book was out.

So what, according to a feminist linguist, does a feminist language look like? Elgin had two goals for this one, based on lacks she’d observed in English and its close relatives:

“(1) Those languages lacked vocabulary for many things that are extremely important to women, making it cumbersome and inconvenient to talk about them. (2) They lacked ways to express emotional information conveniently, so that — especially in English — much of that information had to be carried by body language and was almost entirely missing from written language. This characteristic (which makes English so well suited for business) left women vulnerable to hostile language followed by the ancient “But all I said was….” excuse; and it restricted women to the largely useless “It wasn’t what you said, it was the way you said it!” defense against such hostility. In constructing Láadan, I focused on giving it features intended to repair those two deficiencies.”

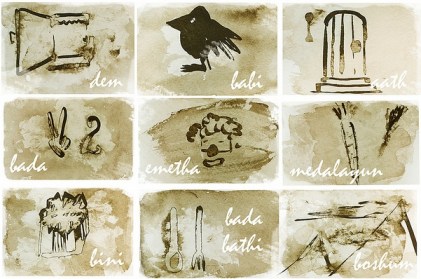

Construction-wise, Láadan is a polysynthetic, or agglutinating, language – distinct, pronounceable syllables each correspond to a small chunk of meaning, and are then strung together to form words. This is a wise choice when conlanging, because then you only have to come up with the small chunks and rules about how they fit together, and compound words take care of themselves. It’s also a good way to make room for detail, clarity, and subtlety – you can build in the gradations that a natural language grows, via careful syllable-stacking. For example, in the Mary story above, the word “wothidá” is simply taken as “wise man,” but, as Láadan scholar Amberwind Barnhart points out, dimensions are lost in translation: “In this word, Dr. Elgin has gone a different direction: she starts with “woth” (wisdom), then adds the masculine ending “–id” to give “wothid” (male wisdom; wisdom as perceived by men) and only then does she add the agentive suffix “–á” to give “wothidá” (doer of male wisdom)—a very different slant from the common English notion of “wise man.”

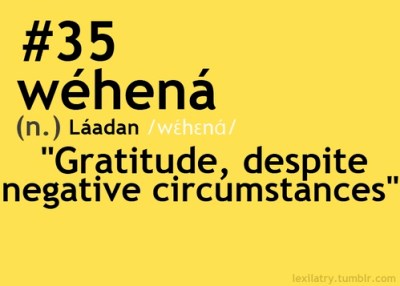

Plus, the building blocks themselves are precise, well-defined, and nuanced (a lot of them are also cleverly designed – for example, “ab” means “love for one liked but not respected,” while its almost-mirror, “ad,” means “love for one respected but not liked”). Just reading through the Láadan-English dictionary makes me feel slightly more in touch with my emotions. Scroll to the B’s and you’ll find five different words for anger, differentiated not by intensity, as in English, but by whether or not it’s justified, targeted, and effective. Go down to L and there are two senses of “belonging,” one rewarding and one oppressive.

Elgin also built in rules meant to clarify intention and degree of credibility. Each Láadan sentence begins with a “Speech Act” word – “I tell you;” “I promise you;” “I warn you;” etc. – which lets the listener know what kind of communication is going on. Every sentence also ends with an evidential, which tells you why the speaker feels justified in claiming that she’s telling the truth (“I saw it with my own eyes;” “I heard it from a credible source;” “It’s self-evident”), almost like a verbal citation. This helps reduce ambiguity as well, and requires speakers to take more responsibility for what they’re saying (although some argue that the larger context of a sentence can undo this).

Inventing Láadan not only gave Elgin more street cred – by actually creating the language, she was able to use it in her book and run a simultaneous experiment in the real world. Elgin hypothesized that if women were offered a language that better fit them, “one of two things would happen — they would welcome and nurture it, or it would at minimum motivate them to replace it with a better women’s language of their own construction.” Now, thirty years after she gave us one, it’s pretty clear that it wasn’t embraced or used as a jumping off point. Elgin considers her experiment a failure, at least within the ten-year time frame she originally gave it to succeed. A small community has grown up around the language, largely online, and fans still create and define words (the largest online Láadan-English dictionary denotes which words are Elgin’s and which are fan-created, and looking at the fan-created ones is like getting a peek at someone’s soul – what does this person most want to be able to express?). Conlangers debate its social and linguistic pros and cons. But no one’s shouting it in the streets. I’ve never gotten to use the word radíidin (“a non-holiday, a time allegedly a holiday but actually so much a burden because of work and preparations that it is a dreaded occasion; especially when there are too many guests and none of them help.”), even though sometimes it’s the only word.

Láadan is certainly a product of its time, its creator, the plot it was created for, and the small community that latched onto it and continues to build it up. Parts of it are ridiculously problematic (starting with the proposition that anyone can presume to know what “women” want to talk about). A similar language proposed today would likely have entirely different goals, not to mention different methods of achieving them. But even if it’s outdated, I’m glad we’ve got Láadan. I’m glad that someone saw the holes in the way she was able to view the world and bothered to try to patch them. I’m downright wéhená about it.

Dear Autostraddle (&Cara),

How is it that you knew to write this article for me? How is it that you are able to combine my beloved, most obscure hobby, conlanging, and also all the other fantastic things that bring me back to Autostraddle? This is indeed a most merry of Christmases.

Whoa. I just-whoa.

YUSS. I’ve only been away from my linquistics degree for 2 weeks but you have filled the hole that the holidays make, with love and joy and delicious words.

I honestly don’t see how a language created solely by one person, without really much publicity, would ever take off, though. Languages need to grow organically, from necessity – and while, obviously, English as a language is irritating and misleading and sexist – *it gets the point across*, even if only just. So many people have created so many languages for so many purposes – and time after time they fail. And as such, I don’t think Elgin’s experiment was a failure at all; while so many conlangs are discarded by the wayside, her vision and aim seems to have kept her language alive, if only as a point of interest than a tool of communication. And I’m glad of that.

This is fascinating. I’ve never heard of Native Tongue but I think now I’m going to read it. Thanks, Cara!

Yes! Conlanging is le awesome. :D

I’ve been meaning to borrow some of Laadan’s lexical features into my conlang. So many of these terms could definitely be useful in life (and not just to women).

I sort of wish we were given more leeway to innovate in modern English; there are so many features I wish we had (namely, case declension, epistemic modality, inflection for suggestions and requests (should and please just don’t cut it for me; I want them in the verb!), no grammatical gender in personal pronouns and more cannonical gender neutrality in general, proximate/obviate and clusivity in personal pronouns, and some other things).

Iel, mi dankas vin pro tiu artikolo! Mi esperas, ke estos pluaj artikoloj pri konstruaj lingvoj en futura. :)

Agreed, Maiya. I’m torn – on the one hand, I love the sloppiness of English, but on the other it can be pretty limiting.

p.s. Do you speak Esperanto?!

p.p.s. Anyone who comments on this article in their own conlang gets some sort of prize, I’m serious.

Ise, aserijis te sopeloi umel melis ube adiolaguhas aha, eso heluku eje dohua. Soa dohua hal ejas la!

Also, by far, the features I like to play with most in my constructed languages are gendered words and pronouns. Pronouns for all the genders!

I win the biggest geekery/show-off award, right?

This is an older conlang than the one I most champion now, but it was more complete. Here is the beginning of the tower of Babyl:

(“o” is schwa, “v” rounds preceding vowel, the rest is pronunced like latin; this looks much cooler in runes)

onk dot Helt Ovrdha wer Harbon Uvmut Spraga,

onk solf Hej Rajzing fravs dot Evzdo s of, Lih wer Habon thaf not Pleno ixs dot Jovrdho ofs dot skin os of Fivndan Hej f,

onk Therij weron Hej.

That’s just a memorized snippet I have of it, and it probably contains typos. The newer iterations are far more elegant and reasonable, but this one did sound nice. :)

Oh, and I do speak a little Esperanto. Not much, though, but I suppose what I know isn’t bad for having only studied it for four days (and that having occurred over 2 years ago).

There’s a lot more to the current versions of it than this dated example portrays. Perhaps I should memorize parts of the new one for future exhibition? I suppose I’ll get to it eventually, lol. :)

Oh, and I think Adrian is better at Esperanto than I.

Jes, mi samopinas: pli artikoloj pri konlingvoj. Eble artikolo(j) Esperanta(j)? Oni povas revi.

cara this is one of the coolest things i’ve ever read. i’m really excited to read some of elgin’s books and to learn more about laadan and conlanging in general. it’s always so neat to discover a brand new thing you literally never knew existed. thanks for that!

this is incredible, cara! i’m so glad you wrote about this because i’ve never ever ever heard of it.

I saw the title of the article and screamed “NATIVE TONGUE!” at the screen. I love that series, although it does rather derail after the second book. The series was also originally published in the 80s by the Womens Science Fiction Press, which I encourage you all to check out. Somewhere I have a book about a lesbian vampire yoga instuctor who gets into a fight with Virginia Woolf in a bathroom.

Haha! Pretty sure you’re legally obligated to dig that book out and send me the title. You know, for science.

“a book about a lesbian vampire yoga instuctor who gets into a fight with Virginia Woolf in a bathroom” That’s amazing. Well, at least there’s plenty of time before next Christmas to hunt it down!

Totally fascinating. Always thinking we all need to be more experimental with language. This article encourages me to take more command and master the language I use. Then I’ll start branching out. Surprisingly inspiring stuff ;)

Interesting, I hadn’t heard about this either. Thanks!

This is my favorite article. I can’t even express my enthusiasm for it in just one sentence. So well written! I’m going to put this everywhere. I WILL WALLPAPER ROOMS WITH IT. FJDKSLFJSAKL

Also, the world of native tongue sounds like the worst and best place all at the same time. YOU MEAN, AS A LINGUIST, I CAN BE HIGH CLASS AND VALUABLE?!?! BUT AS A WOMAN I CAN BE NOTHING?!?!?! UM.

This is so very interesting.

There needs to be Rosetta Stone App for this.

My brain is tingling from all this awesomeness!

I was trying to explain to my boyfriend why there are so many words in this language that we need in English. He just didn’t get it. “Why do you need a word that means ‘to have your period for the first time’?” Umm, BECAUSE.

So many words I never realized we needed BUT WE TOTALLY NEED THEM YOU GUYS.

PS I really appreciate that the word for ‘clitoris’ breaks down to ‘fragrant jewel.’ Because yes.

Aihr’tivh qiuen sienen sahraerha kreh! (This is the most amazingly awesome thing ever!)

Also: mi lernis Esperanto, sed mi forgesis… there are a considerable number of issues I have with that language, but that’s neither here nor there.

Firstly I’ve now got some books to track down to read, and that’s always a good thing.

Secondly, as a semi-linguist (I’m not done my degree), the idea for this conlang is fascinating. I’ve often thought about how much of an effect (if any) a language has on perceptions of women/degrees of misogyny etc (and generally concluding that if there is any, it’s negligible). I’ve never considered the idea of a female-centric language, though… this is really intriguing me.

Given that there are many concepts that have a word in one language but not in another (requiring them to be translated with a sentence, if at all accurately translatable), I’m now wondering whether other languages have words for female-specific concepts that don’t have words in English…

And thirdly, I used to be pretty active with conglanging, did a bunch of random stuff, though my two main projects were expanding Rihannsu into an actually-usable language (even got as far as starting to translate Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar into Rihannsu), and another that was based on the extinct Dalmatian language… and it’s always, always cool to see that one isn’t alone!

Off to go find and buy these books…

Pingback: Auto Body Repairs Elgin In 94083 | Auto Repair San Francisco

Pingback: Láadan and the Monthly Curse | Fractal Fortress

I’m in the process of learning Laadan because I find it to be so aesthetically pleasing. Not only that, but as an autistic person, I really appreciate how Laadan eliminates a lot of ambiguity that English has. I’m not good at reading between the lines or understanding body language, so its nice that Laadan makes that kind of thing explicit instead of just implied.

Pingback: Láadan and the Monthly Curse | Fractal Fortress