feature image via shutterstock

It’s almost Autostraddle’s own Babe-B-Q weekend! We’ll be hanging out with each other August 15 and 16 to grill up a storm, and everyone’s invited! We’ll also be guiding you through the process of grilling up said storm and getting prepared for the big event all week. You can view all Babe-B-Q posts here.

As a person whose dental adventures seemingly never come to an end, I’ve developed a real soft place in my heart for soft foods. So for today’s topic, I thought we’d talk about how to soften up other tough muscles! With science! Get pumped.

What makes you so tough, huh?

Okay, first things first, I’m the realest. But um, first things second, all meat consists of muscle, connective tissue, and fat. Most of what you see are bundles of protein fibers, which provide structure and (when we put it in our mouth) a chewy toughness. These proteins can be divided into three general categories:

- myofibrillar proteins, which enable muscles to contract

- stromal proteins, which provide structure to connective tissues, including tendons, and

- sarcoplasmic proteins (e.g., blood).

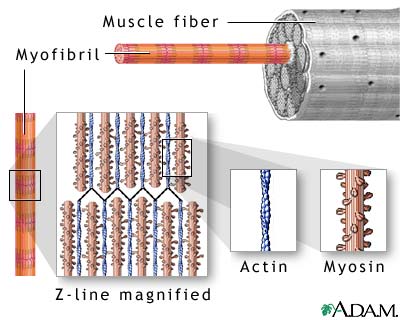

When it comes to texture, the most important are myofibrillar proteins, which account for about ⅔ of the proteins found in mammals. Within these, Cooking for Geeks: Real Science, Great Hacks, and Good Food explains: “Myosin and actin are the most important from a culinary texture perspective. If you take only one thing away from this section, let it be this: denatured myosin = yummy; denatured actin = yucky. Dry, overcooked meats aren’t tough because of lack of water inside the meat; they’re tough because on a microscopic level, the actin proteins have denatured and squeezed out liquid in the muscle fibers.”

Within each muscle fiber are strands of myofibrils. These long cylindrical structures appear striped due to strands of tiny myofilaments, which have two types of protein: actin (thin myofilaments) and myosin (thick myofilaments). Via Penn Medicine.

Also important to meat texture are the stromal proteins — namely, collagen. For many cuts of meat, collagen mainly shows up as discrete pieces, such as tendons or silverskin. These can simply be cut away before cooking. In other cuts of meat, however, collagen forms a tough 3D network through the muscle tissue. This is most effectively removed through long, slow cooking methods which convert the collagen into gelatin.

The tricky thing about all this is that the more you cook muscle, the more the proteins firm up and dry out; yet the more you cook connective tissue, the more it soft and tender it gets. Through empirical research, food scientists have determined that there’s a sweet spot for the internal meat temperature between 140-153F/60-67C, where myosin and collagen will denature but actin will remain in its native form. There’s a lot more to be said about the chemistry of cooking meat, but for now we’re going to focus on the food prep stage.

There are five things people commonly use to tenderize meat during food prep: acidic marinades, proteolytic enzymes, brines, dry rubs, and mechanical tenderization tools.

Acidic Marinades

Marinades have been used since Renaissance times to slow spoilage and provide flavor. When the acids in the marinade come in contact with the meat, they denature the protein bonds, uncoiling the actin and myosin filaments. The electromagnetic properties also disrupt collagen’s helical structure, untwisting the strands and chopping up the “backbone” of the structure through hydrolysis. Unfortunately, the effect is actually quite limited, as it only works when there’s direct contact. Marinades penetrate slowly, and no matter how long you let it sit, they tend not to go any more than ⅛ of an inch in.

Among professional chefs, you’ll often see marinades used as more of a surface treatment on thick cuts. To increase the tenderizing effects, they’ll sometimes put gashes in the meat or inject marinade inside, allowing the acid to come into direct contact with more surface area. Alternatively, one could also stick exclusively to thin cuts of meat, like the skirt steak Chef Susan Feniger uses in this recipe:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WEkK08GPAnY

Brines

A brine is a liquid with 3-6% salt by weight. Meats are typically immersed in brines for anywhere from a few hours to a few days before being cooked, with the effect of making the final product much juicier than it otherwise would have been.

On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen describes the scientific reason:

Brining has two initial effects. First, salt disrupts the structure of the muscle filaments. A 3% salt solution (2 tbsp per quart) dissolves parts of the protein structure that supports the contracting filament, and a 5.5% solution (4 tbsp per quart) partly dissolves the filaments themselves. Second, the interactions of salt and proteins result in a greater water-holding capacity in the muscle cells, which then absorb water from the brine. (The inward movement of salt and water and disruptions of the muscle filaments into the meat also increase its absorption of aromatic molecules from any herbs and spices in the brine.) The meat’s weight increases by 10% or more. When cooked, the meat still loses around 20% of its weight in moisture, but this loss is counterbalanced by the brine absorbed, so the moisture loss is effectively cut in half. In addition, the dissolved protein filaments can’t coagulate into normally dense aggregates, so the cooked meat seems more tender.

The downside to this, of course, is that soaking in brine naturally makes the meat much saltier. To mask this effect, many cooks add other flavors such as sugar, spices and vegetables. Chef Anne Burrell demonstrates how to make one such “brinerade” below:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KLwa1oYfOjY

Dry Rubs

The acids and/or salts in dry rubs work in the same manner as marinades and brines; they just have less penetrating power. (Duh.)

Really I included this method because I wanted to show you this video of Chef Elizabeth Falkner making pork chops:

That hair, you guys. And that outfit. Hot fire. (Also she seems like a very capable woman who is extremely knowledgeable about her profession and stuff. So, right on.)

Sugar is sometimes used in dry rubs to balance saltiness and help the meat brown better by creating a caramelized crust on the outermost portion of the meat. Flavor-wise, this translates to deliciously strong smoky and charred flavors. Or when applied in different stages, cooks sometimes also use dry rubs in combination with other tenderizing practices, as Chef Tiffani Faison demonstrates here:

Proteolytic Enzymes

As far back as pre-Columbian Mexico, cooks found that wrapping meats in papaya leaves before cooking had a tenderizing effect. The reason: papayas contain an active enzyme known as papain, which digests protein! A number of other plants have proteolytic enzymes as well, including pineapple (containing bromelain), ginger (zingibain), fig (ficin), kiwi (actinidin), and certain types of fungi.

Awesome as this is, however, direct contact is once again required for the effect to take place. Proteolytic enzymes penetrate only a few millimeters per day, so it’s usually not advisable to leave the meat immersed for a long period of time. (Unless the cook purposely wants the outside surface to become mealy while the inside remains unaffected. But um, yuck.) Although the enzymes act slowly at refrigerator or room temperature, they can go up to five times faster when heated between 140-160F/60-70C. Some slaughterhouses actually inject papain to the animals right before slaughtering, with the idea that the injected enzyme will be carried through the bloodstream to all parts of the animal and later become activated by the cooking process. This sometimes results in inexplicably mushy meat. For the individual cook, a much better bet is to apply enzyme somewhere between 30 and 60 minutes before firing up the grill.

Although tenderizing via proteolytic enzyme meat tenderization is currently less common in the United States, the practice is well-known in many other cultures. For example, papaya marinades are used in Lao cuisine:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GPI8jLsUi3U

Interestingly, the more familiar American practice of “dry aging” steak works in exactly the same way; it just allows the enzymes naturally present in the meat to do their thing, rather than a cook artificially adding new ones. Dry aging also alters the flavor of the meat, making it taste gamier — so proceed with caution if that’s not what you’re into. Dry aged retail cuts are typically 5-7 days old, but some restaurants use meat aged 14-21 days.

Mechanical Tenderization Tools

There are two schools of thought when it comes to mechanical tenderization:

- Attacking meat with a series of sharp, pointy things to cut through tough meat fibers

OXO Good Grips Bladed Meat Tenderizer in action. Via Whiskey Bacon.

- Breaking the fibers down by beating the heck out of meat with a hammer-like tool or other hefty object

Via Food Wishes via dish.allrecipes.com.

There’s no chemical change to the meat during this process, so in some people’s opinions, this qualifies less as “tenderizing” and more as “masking toughness.” You can achieve a similar effect by slicing meat against the grain after cooking.

Via BroBible.com. (HA!)

Happy grilling!

Notes From A Queer Engineer is a recurring column with an expected periodicity of

Notes From A Queer Engineer is a recurring column with an expected periodicity of one month 14 days. The subject matter may not be explicitly queer, but the industrial engineer writing it sure is. This is a peek at the notes she’s been doodling in the margins.

This is great! Loved *loved* the science part of why meat is tough!

And I was even just thinking the other day about finding some ox tongue recipes to cook! Thank-you Laura!

Yay! Good luck with the ox tongue!

MEAT. FOOD.

My grandma has this method and we dont know the science behind it but when they cook something with meat they boil it with a silver fork..has to be a fork, no spoon..and the meat turns oit really really tender!!

Huh. How interesting!

I love everything about this!

This is fantastic! Very informative! Thank you so much, I love to learn the science behind cooking. :)

I’m glad you liked it. :)

BUT HOW LAURA

HOW DO YOU TENDERIZE

….YOUR HEART

Stef.

<3

Thank you for the food science! This was awesome

In my country we cook meat with grape leaves. Like we make beef/lamb based dolmas and they come out really nice, when cooked right. I think the meat is cooked first, then mixed with the rice and other things, before put in the grape leaves to be cooked again. I think the moister in the grape leaves adds an extra level to the tenderness.

Food

Science

Meat

Grilling

These are a few of my favourite things.

When the day bites

When idiocity stings

When I’m feeling sad

I simply remember a few of my favorite things

And then I don’t feel so bad

Thank you Laura who is rad

I don’t know what happened up there, but I’m glad.

You’re my favorite thing, is what happened. I’m glad too.

<3

I don’t eat meat. I just clicked here because science & because Laura wrote it. And it was totally worth it. thumbs up, 10/10, would recommend.

I’m blushing. That’s a really sweet thing to say. Thank you.

Nice article!

Yoghurt can also be used to tenderize red meat but takes 4+ hrs at room temperature